Above: a view from Onitsha toward the Northeast, beyond the small valley of the Nkisi Stream. The hilltops beyond were mostly forested during the early 1960s.

Author’s Note: This is not an easy page to write, partly because the events were set aside in memory so quickly — there were so many other things we had to do, and at the time of visit I failed miserbly in my elementary ethnographer’s tasks: to take regular field notes — partly because the trip was in many ways so painful, the events so distracting. On the night of our second day in Onitsha, my wife Helen fell into a large streetside drainage ditch and broke both ends of the tibia and fibula where they connect to her left ankle. I (the still-living prime story-teller here) fell into a version of what I’m sure we would today call Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder, a kind of psychological frenzied condition which did not abate much during (and for some time after) our then-shortened visit (while Helen, so far as I could tell, remained fairly calm and positive through it all). Therefore the ethnography of this report will be scattered and rather disorganized, reflecting my own “fractured” condition. I will proceed where this is feasible by presenting images (including substantial video records, which will be woven into the text where appropriate.), but I’ll also recruit helpers to support me through.

The Plan of Travel & Research: Nneka Umunna and Helen Henderson

The fact was that it was Helen who instigated a return to Nigeria In 1992. At that time, she was working eagerly on research into feminist-related matters, and working in part with Nneka, she was examining the history Nneka had told her about her maternal kinswoman, Nne-Ce — the -Ce being short for “Cecelia”. Helen evolved a lot of plans for working with Onitsha women at this time, and I agreed to accompany the two women to Onitsha, hoping for my part to meet some of my old friends there. So the trip was organized, with Nneka contacting her many relatives there and Helen and I collecting the necessary items (including a video camera to take with us).

Arrival: Unrecognizable Country and Cities

Our trip was uneventful until we arrived at Murtallah Muhammed Airport in Lagos. On the tarmac, we were surprised (and delighted) to find a phalanx of Onitsha people there — not in the “waiting rooms” but standing right beside where the plane landed. The group, composed of Nneka’s brothers and Ifekandu Umunna’s sister, escorted us into the airport building. I fell behind for some reason — carrying my camera equipment and a backpack was probably my problem — and I was accosted by a small but well-armed policeman (or military officer), so I called out to the others well ahead of me. They saw my plight, returned to my side, and simply led me away en masse. They did not negotiate with the official, simply led us away.

Outside, we got into two passenger cars and proceeded toward Lagos. We were pulled over somewhere along the Ikoyi Road by a car carrying two “policemen”, who demanded to inspect our luggage. I offered to allow this, but our escorts refused to open anything in our luggage. Ifekandu’s sister, who was married to a naval official, pointed out her social status and said she would report these men to the proper officials. After some confrontational moments, they gave up and we continued into Lagos where Nneka’s brother Olisa had an apartment.

We stayed there very briefly. My one vivid memory is of the overhead fans, rapid-spinning steel blades, whirring a foot or so above our heads. One of Olisa’s sons had been raised overhead by an enthusiastic parent and had suffered a severe injury to his forehead — he was seriously, obviously scarred, and that was a troubling feature of our visit.

I remember little of our preparations, but we were set up to go straight across the country to Onitsha by means of an Igbo-owned bus service, Ekene Dili Chukwu. This was another unforgettable period, with the drivers of this very well-organized service being subjected to multiple stops along the way by various dubiously-garbed (but well-armed) “authorities” making demands for payment, one “policeman” forcing our driver to kneel and “beg” while offering money to this particular one of various gangsters waiting along the way.

Then we were crossing the already-fabled Onitsha Bridge, and I heard on the radio Ndi-Onicha talking about their various Village members who were requesting music to be played, a very welcome feeling. But, crossing the bridge, the town itself seemed unrecognizable.

Finding a home base in a context of Fear

We arrived at Obikporo, Nneka’s home village in the Inland Town, and were greeted by the family members. They were of course very happy to see Nneka, and were cordial to us, but when we inquired if we could stay there overnight, Nneka’s father became seriously alarmed and said, No, this would not work; it was too dangerous for them to harbor us there. Thieves would attack the place in the night.

At left, Nneka a few days later, at the entryway to her father’s compound.

I’m unsure how Frank Omekam managed to appear at Obikporo during this day. The family must have summoned him (as a lineage-maet of Nneka’s late husband Ifekandu), but however it happened, he took charge of our situation. He knew a good place to stay and he had an operating motor vehicle which could transport us there (and be made available to us as we needed it afterwards).

The house was on Nkisi-Aroli Street — a location where homes were occupied mainly by Umu-Eze-Aroli people and which ran toward and ended close to the Nkisi Stream. The streetsides were now filling up with new (and under-construction) houses intended for the well-to-do in Onitsha. We eagerly took it up and moved into it. (I’ll show more of our living situation further below.)

At the far bottom of the street, I found this very substantial termite mound. I thought this was a good omen, because in the 1960s and later1, I had discovered the very strong symbolic importance of termite hills in Onitsha (and other Ndi-Igbo) religions, but I had never actually seen a significant one on Onitsha lands. (And what appeared to be a protective shrine table was in fact located on the far side of this one).

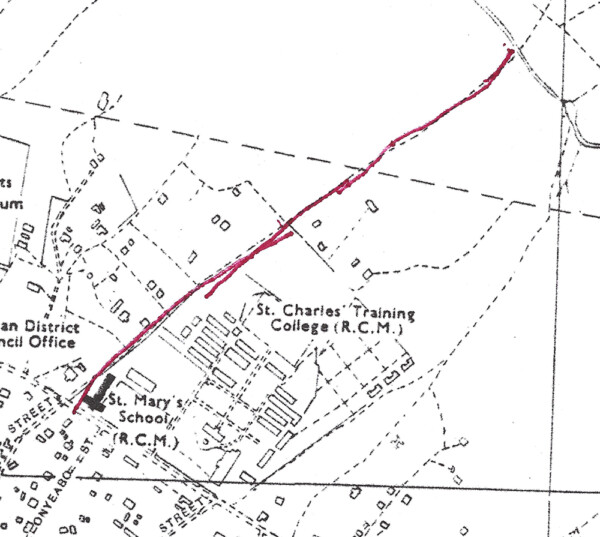

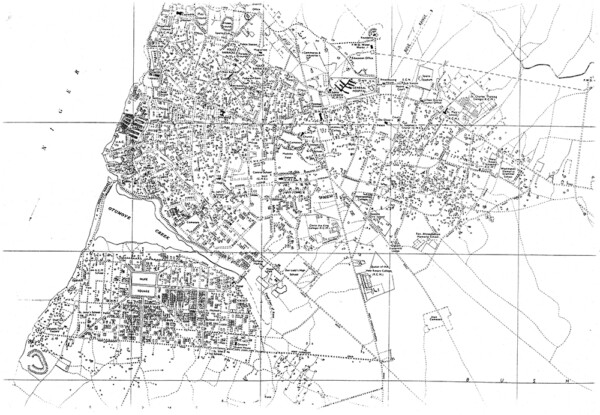

At this time I had not clear sense of exactly where in Onitsha Nkisi-Aroli street was located (though I traversed it on a daily basis this was strictly as a passenger while Frank was driving). The 1957 map at left shows what I feel sure was the ancient Nkisi-Aroli trail where , during the 19th century, residents of Umu-Aroli walked to fetch their everyday water from Nkisi stream. By 1992 these formerly empty northeastern edges of the city spaces were becoming well-occupied, and the trail had become an appropriately-named street.

Helen’s successes, then her Serious Fall

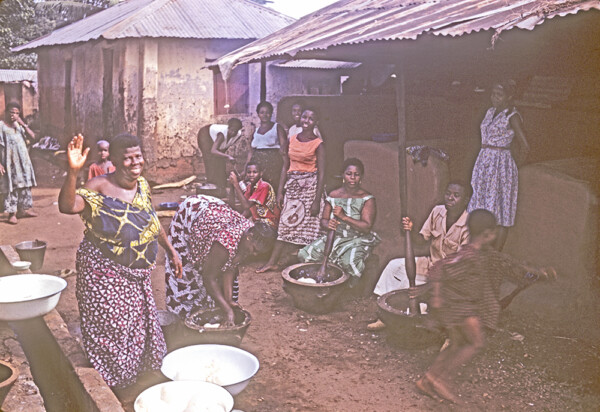

Nneka recruited helpers for us at the Nkisi-Aroli house. It was quite large (if sparsely furnished), and we needed only the ground-floor spaces for our use. Nneka’s young sister Emengeni acted as our cook, becoming a very helpful and pleasant presence in the house during the daytime. Helen quickly organized a reception to meet some of the nearby-residing Onitsha women, who came and gathered with us one night soon after our arrival.

This was a very successful meeting Helen told them of her desire to learn much more about the social rights and responsibilities of Onitsha women, and they responded with eager interest, as the nascent group planned for further meetings to consider what activities they might organize and conduct together in and about the town. A visit to Chief Etukokwu, who had worked for many years in support of Onitsha women, was placed prominently onto the schedule of this new research group.

Late in the evening, the lights in the building suddenly went out, and we soon learned that this condition, a widesprad urban blackout, was a regular occurrence in Onitsha. The visiting women arose to leave, and Helen insisted that we must accompany them with a flashlight out to where they could feel safely conducted to a location near their homes. They protested, but Helen was adamant — she knew from our previous years in Onitsha that this was the appropriate Ndi-Onicha way, to escort visitors from your home at night, being with them halfway to their villages. So out we went, I carrying the one flashlight we had found on hand. The surroundings were totally dark.

We walked uphill on Nkisi-Aroli Street in this condition, with me flashing my meager flashlight back and forth over the surfaces of this very rough street. It was relatively firm for walking but full of small pot-holes and not easy to traverse especially at night. We were making fair progress however, when suddenly Helen — who I noticed had forgotten to wear her glasses (being extremely myopic without them), suddenly moved sharply to the right as we progressed uphill, apparently seeing some better-lit space in that direction. I was startled, I think I said something to her, but she had apparently “seen the light”,, and she propelled herself rapidly rightward — and into the large, concrete-lined drainage ditch off at the side of the road. She fell into it like a stone.

this must have been a great shock to everyone present, but it was immensely so for me, since I knew at once that she had to be badly hurt lying down there. I rushed over, handed the flashlight to someone else, and got down into the ditch by her side. She was conscious, but I think somehow badly stunned. I got her seated a bit and then reached down to feel her ankle, which she let me know somehow was hurting her considerably.

It took a while for me to feel around it, but I soon could tell that something had been broken. Frank was standing nearby, and he kept saying, “it is dislocated”, but I made it clear that something was broken. We called for transportation, and asked about hospitals.

Someone said that, closely nearby, there was the Evolution Hospital, which boasted a doctor who dealt specifically with broken bones..Eventually someone arrived with a taxi, the rear doors of which I seem to remember opened forward (which seemed very strange to me, and they kept opening as we got in and then began to move). Others got in the ditch with me and lifted her out, while I held on carefully to the right leg at the ankle, where I could feel the broken bones. I was much afraid that the bone shards might cut through an artery somehow. But with minimal difficulty we got her into the rear seat of the car, with Nneka beside her, and with me on her right we drove off to the Evolution Hospital.

I’m not sure exactly where this place was. It was not far, I think, from Nkisi-Aroli, but it was a three-storey building, and every fooot of it was entirely dark inside except for what appeared to be light from a single candle located somewhere on the top floor. Helen said quietly to Nneka, “Please don’t put me in there…”, but of course that option was entirely discarded at first sight of the place. Someone said, “Let’s try St. Charles Borromeo,” so we drove off toward the hospital which we had never seen, but which was located, in the early 1960s, on the northwest side of town.

Saint Charles Preserves Us

We arrived at the Hospital, and LO, THERE WAS LIGHT! The St. Charles Borromeo Hospital had its own generator system.

A locally-built wheel-chair (it made use of bicycle wheels, and had been roughly welded together) was brought out, Helen was seated upon it, and we proceeded to the entryway where patients were admitted.

Two Ndi-Igbo Doctors followed behind Helen. I remember this vividly because, when the Admitting secretary asked Helen her religious affiliation, the momentary idea popped into my head: “Free-thinker” (?) I thought — while Helen responded without hesitation, “Protestant”, whereupon one of the two doctors jumped visibly.

This is a vivid memory because (1) the Catholic-Protestant divide has been so prominent and politically so salient In Onitsha for such a long time and (2) I wondered how they might treat her.

I need not have worried: they immediately assigned her to the “Bishop’s Room”, which fortunately for us was not in use at the time. It had an air-conditioner unit at hand, which apparently did not work, but this was unimportant — Helen was comfortable here throughout, and she was very well treated by everyone from start to finish. I remember this hospital and its staff with a great deal of fondness.)

Nneka and her sisters proceeded to organize the provision of Helen’s feeding and other necessities during her stay. (one of Nneka’s sisters stayed with her overnights.) The doctors set up her X-ray procedure prior to fitting her with a cast. I observed that the length of the X-ray’s running was about 30 seconds.

Below,, the doctors look over her leg. They did a fine job stabilizing the bones, but suggested that — while they were willing to do further operations — we would probably prefer to take her home for that.

Back in the Nkisi-Aroli house, the lights were again working but, left alone for the night, I had feelings of great discomfort. The surrounding walls of the complex were surmounted with plastered shards of broken-glass for protection against thieves, and the windows were strongly barred, but this did not give me a sense of much security. I was now alone in the dark night of this suddenly unfriendly-feeling city. The nearby whirring of overhead steel blades did not lend me much comfort, and I now had to begin calculating the means and time of our impending departure..

Ifekandu’s Grave (Iba)

Not far from Nkisi-Aroli house was the location where Ifekandu Umunna had purchased a small portion of his major Village’s land and built a small house on it to fully stake his claim within the community from the standpoint of a diaspora person. I think Frank may have assisted him in organizing this process — living in Onitsha and in the same sub-village (Umu-Anyo) where Ifeka grew up, they had done things together.

When Ifeka suddenly died in late 1989 — we were age-mates; he had died of a sudden massive heart-attack at age 58, which was a hard shock to all of us who knew him well but disastrous for Nneka with her two boys of age six and 10 at the time. Nneka (and her boys) had accompanied the corpse back to Onitsha and participated in the burial process, Ifekandu now resting in a grave just outside the house. I know this whole process was devastating to Nneka and her sons, especially damaging for Obi, the older one, who had bonded very closely with his father. Ifekandu was an unusually skilled and socially-responsible husband/father (and age-mate; friend to any moral being and my very-best friend when he died), and his loss at this time was a major catastrophe for all of them. To top that off, bringing hs corpse hack home to deal with the elaborate ritual processes engaging his surviving Onitsha relatives was without doubt beyond disorienting — dismaying, and worse. (For years after it Nneka found it difficult to discuss at all.)

Chief Etukokwu and his Castle

Since Helen had planned to begin her research with a visit to the Onitsha Chief Odua Etukokwu, who was well-known in the Inland Town for his support of women’s interests there, I decided to proceed to his Castle (it was always referred to by that label, in part because of its massive construction) so that I might begin to make some of that effort on her behalf.

Frank drove me there — see below a view of Etukokwu Commercial Collage looming high above Ojedi Road. In he early 1960s, the College was a very striking feature here on the edge of the Inland town. Note here in this image, in the ’90s, the extreme traffic congestion along Ojedi Road. Residents told me this was a chronic, if not continuous condition due to frequent traffic stops made along the Awka Road by the (Norhtern-based) police units now controlling Onitsha. Not also the patterns of erosion along the edge of the street alongside the concrete-lined vertical ditches, definitely a hazard for pedestrians especially at night. We were headed for the entryway to Etukokwu’s Palace, located on the far side of the main College tower in this image.

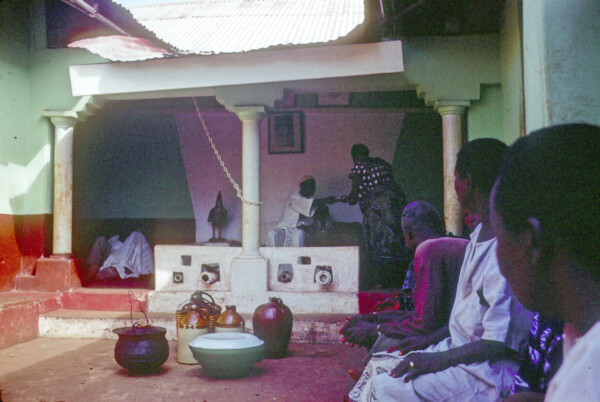

Below, the entryway to the palace courtyard. Note first the interesting color combinations. Oduah Etukokwu has paid careful attention to the color layout, and one sees this attention to detail everywhere. Second, observe the sculptural touches, for example the iconic elephant sculpture at mid-image on the right. Things like this appear in unexpected places in all of the interior rooms here. Third, observe the vegetation. There are decorative gardens everywhere, all of them carefully tended. Beyond these kinds of detail, one will find a substantial operational aquarium and a large, inhabited bird cage. The place is full of aesthetic elaboration.

We entered the interior courtyard, which was quite dark. Several men were seated around Oduah Ekukokwu, who sat at his desk.

Frank arose to introduce me, saying I had come to study Onitsha custom. One of the men gazing at us responded: “This man must first read the work of Dr. R. H. Handerson, who has written…” Frank interrupted: THIS IS THE MAN.” he said. All three of them stood to spontaneous attention.

This was the first moment when I learned that I had become something of a “Celebrity” for many Onitsha people. If thirty years had intervened since my previous visit, for twenty years Ndi-Onicha had been able to read my published book about their cultural history, The King in Every Man. I now learned that it was widely respected, a fact that surprised (and quite pleased) me. They greeted me profusely.

Among them was Chike Akosa, whom I had met briefly while in Onitsha in 1961. Well-known for his prodigious memory (my friend and colleague Josef Gugler once described interacting with him as “an encounter with Total Recall”), he had published an important book for local people, “Heroes and Heroines of Onitsha”, and was locally active in furthering Ndi-Onicha interests. We definitely shared strong common interests in Onitsha history and culture, so we arranged to meet again for more discussions. Helen’s protects regarding women somehow never entered our discussions at this point.

(We did manage to get together briefly, but not to the extent i had hoped. Chike invited us to a gatherinng where some Northern officials met with Ndi-Onicha to discuss what I understrood to be a projected future effort to amalgamate prinjciples of Islam with those of Christianity, an idea which seemed to me of very dubious prospects. It was a brief moment of which I later heard no further details.)

My visit to Oduah Etukokwu’s palace cannot conclude without a brief further examination of this man’s primary Throne Room, centering on his personal Ukpo:

Below, a view of a sculpture placed immediately left of the throne. i am unsure of what animal this represents, though my best guess is that the artist intends a lion. It certainly presents an open mouthful of fierce teeth. 2 Note also another image of the Oduah along the far wall.

Frank Omekam’s Building in Umu-Aroli

At left, Frank’s house fills the far side of the right-hand portion of the image. (He stands beside the barred window.) This is a relatively hi-tach building in my experience of Onitsha houses. The electric connections were quite sophisticated. This is a product largely of Frank’s design, indicative of careful attention to technologies.

This is the Iba (Ancestral House) of Frank’s father as it appeared in 1962, roughly in the same location as the 1992 building. Observe the Egbo tree growing out of the central courtyard, emblem of the founder’s connection with Mother Earth, marking the place as an iconic iba.

Here we look downhill from Frank’s house toward Jagwo Road. You can see that much of the land spaces open in 1962 are now well-filled with buildings.

Now looking back across the Umuanyo upland behind Frank’s house in the direction of Bishop Onyeabu Road, Obiekwe Aniweta’s recent house contruction comes into view. A very massive three-storey building, it dwarfs his former home, his father’s Ancestral HOuse where Helen met with his mother to learn about her Chi rituals in 1961 (below).

Reconnecting with Obiekwe Aniweta, Protean Man

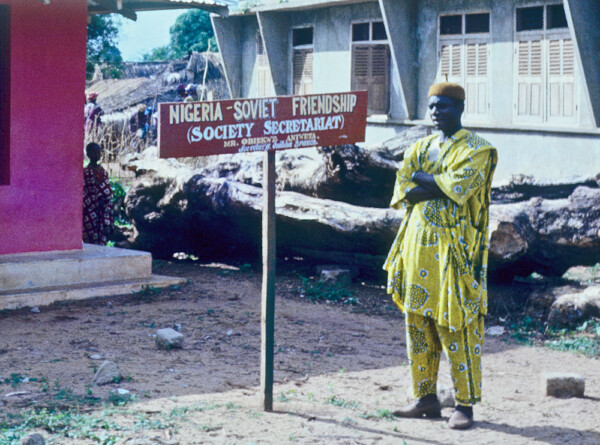

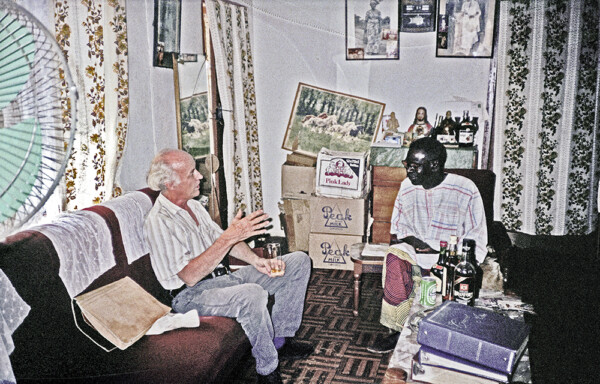

In 1961, Obiekwe expressed firmly Communist opinions — he published a fairly lengthy Onitsha Chapbook, The Church and Communism (mainly attacking the behavior of the Roman Catholic Church in Onitsha) and he repeatedly said to me, “I think I am going the Chinese Way.” (These were Maoist times, and he was thinking seriously.)

Now, in 1992, he had completed a very substantial mansion near the site of his father’s Ancestral House, and he greeted me there for a visit. His circumstances (and worldview) had sharply changed once again, and he showed no indication of looking backwards.

The interior of the house indicated careful attention to protection. Various entries were locked. I did not “look around” this house; we just went to the upstairs and sat with him in a small reception room.

Obiekwe said to me when we met, “Mister Henderson,” (he always addressed me thus),”I have become a capitalist!” As you can see, his dress surely implied as much. When I saw him here he was always attired in a dark suit-and-tie, topping things off with an English-style bowler hat. And here he sat on a woven carpet the icons of which denoted a foreign bank. (He told me, in passing, that he now had four wives and 25 children, if I recall this correctly.)

I do not mean to diminish Obiekwe by this description. It is true that my impression of how Onitsha people regarded him, at this time and later, was very mixed (as was true as well in 1961). But he had been through some difficult times: during the Biafra Civil War, he had joined the rebel forces in an advisory role, but the reputation of Ndi-Onicha from the perspective of Biafran converts declined sharply during the course of the war, and Obiekwe, along with a number of other Ndi-Onicha intellectuals, were put in jail by the Biafran regime at one point. Obiekwe lost the use of one eye during this imprisonment. We did not talk much about this history during my visit (my impression is that memories of the Biafra Wartime were and are mostly well-buried in Ndi-Onicha’‘s minds).

During this time, he also took me to see some of his friends one evening, a very pleasant occasion which unfortunately I hardly remember now (having failed severely in my note-taking tasks during this whirlwind time, as I observed in the Introduction to this page. I was impressed with the character of some of his friends. And he boldly escorted me to an encounter with his former patron, Igwe Enwezor, for whom he had worked hard during the 1960-62 Interregnum (but had later fallen away from him3

Visiting Igwe Enwezor

I learned from Aniweta that Igwe Enwezor was “at home”, so I decided to visit him there. Looking back, I am unsure of the sequence of events, but in one visit I took pictures of the frontage of the palace, and on the other visit I took no pictures but passed some of my own around inside the meeting chamber where we met the IIgwe. I here present what I saw outside: first the images, then I will describe the visit where Igwe Enwezor actually appeared. 4

Here, left you see the central portion of the Enwezor palace compound from the street. The two-storey palace “wraps around” a more front-and-center structure which I quickly recognized as the sole remnants of Igwe Enwezor’s old Altar from his Ancestral House in 1961.

Here is a closeup of the altar, you can see the cannons more clearly. The white, clown-like figure at left is a recent addition.

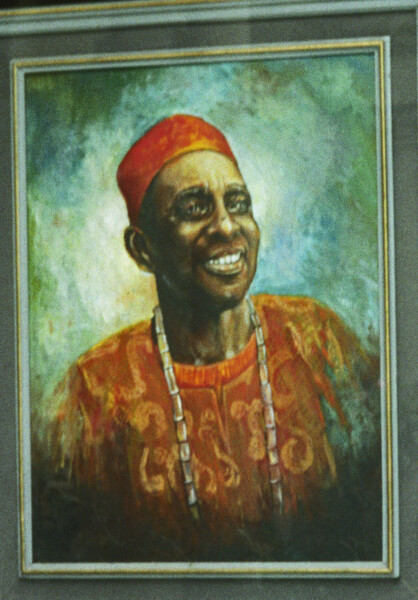

That original altar appears in the photo at left here, taken when Igwe Enwezor celebrated the Uwaji (“new yam”) festival in this building in 1951. This house was a massive, multi-room single-storey concrete structure, its altar festooned (as you cn see) with an array of four fiercely-out-facing, old-Portuguese-style cannons, an array unlike any other altar I saw in early 1960s Onitsha. To me it clearly conveyed an imagery of threatening power, more strongly than — for example — that classic American example of the image of a coiled snake with the message “Don’t tread on me”. I say this despite the fact that in my experience Igwe Enwezor presented a rather gentle, accommodating presence. This altar radiated a threat demeanor.

At left, , after turning left from the central courtyard of the palace, I encountered this astonishing fresco along one wall. I say astonishing because l never saw anything remotely similar to it in Onitsha Inland Town. In it you see a person who obviously represents Igwe Enwezor, holding in his right hand the brass sword representing the overwhelming powers of kingship..

A closer view of him, at left, shows a person who does not signal the confidence of a great king, a visage, unmistakeably Enwezor’s, who indeed looks quite frightened.

At left, a closeup of some of his acolytes, quite young-appearing boys bearing bronze-looking staffs. One of them has a cape that almost looks like winngs. Behind them, and almost in shadow, two senior figures stand. I think the one in front represents Enwezor’s senior son, who I met elsewhere in the complex working on family affairs. Here he looks alarmingly uncertain, apparently gazing toward his father. The other elder is nearly invisible.

Below left, close by the main entry to the palace courtroom, we see what may provide some resolution to our perplexity: a life-sized and very feminine-appearing Jesus stands crucified. Partly for aesthetic reasons, this image provides a real shocker: this is almost a pornographic Jesus (see in the image below right).

In contradiction, a very different personage stands nearby,(below) and even closer to the entryway: on a pedestal standsl a bronze (?) figure with lion-like teeth (and what may signlal an encompassing mane) in a threatening posture. I had never seen anything like this in Onitsha (but elsewhere — in Etukokwu’s palace — I did see what looks like a comparable figure).

When Aniweta and I eventually entered the courtyard of Igwe Enwezor’s palace, I found a large open room with a number of folding chairs scattered here and there, not arrayed in any order. I was greeted — if that is the right word — by a woman of middle age whom I had never seen before. Obviously — it had been thirty years since I had seen the Igwe — this was one of his newer wives. (I saw none of the ones I remembered from 1961-2.) This woman was obviously not pleased to see us, behaving with a very unfriendly attitude, and I realized that Aniweta must of course be a very unwelcome visitor to the Igwe’s house. 5 Aniweta himself now behaved as if nothing was amiss, speaking cheerfully to one and all, while I tried to calm things by handing around some of the photographs I had brought with me (images I had taken of 1960s Onitsha and its denizens), but to my alarm she seized each of them and made as if to take them away somewhere. I made clear that I had not intended them as gifts — they were just aimed to stimulate memories — and eventually they were returned to me. It was clear to me by this time that this person was in charge of the place. No other person displayed any action.

I was reminded by contrast with the behavior and demeanor of Enwezor’s senior wife at the time of his New Yam celebration in 1961. This was a truly remarkable woman, who you see here at left guiding the work of the rest of her extended family in their preparations. The Igwe‘s household was obviously a very harmonious place then. As I sat wondering about her now, I realized this was 30 years ago and (despite her always cheerful demeanor) she was dealing with some problematic ailments at that time.

Finally, Igwe Enwezor appeared. When he saw that Obiekwe Aniweta was present, his face dissolved immediately into expressions of great fear. Seeing this, I called out to him, identifying myself and offering many thanks for the kindnesses he and his family had shown to me when I visited them in the past (which were inndeed real facts). His face immediately dissolved into expressions of warm pleasure.

It was clear to me from that moment that Igwe Enwezor was in the far reaches of dementia. After a brief while we left, and afterward I began to realize that he was obviously in the hands of some kind of evangelistic movement, probably under the control of this new wife. In my experience elsewhere in 1992 Onitsha, I would find that many married women seemed to enjoy ignoring their husbands’, fathers’, and other authority figures’ priorities, sometimes by singing scatterings of Christian hymns while he was trying to talk with visitors — a pattern that had not been seen by me in 1960s Onitsha. Evangelistic Christianity was spreading its wings widely in Onitsha at this hour.

Remembering The Aborted Reign of Obi Onyejekwe

Frank and I briefly visited Okwu-eze, the sacred grove dedicated to Umu-Eze-Arol Kings who had ruled in the past, and where Obi Onyejekwe had built his own palace after winning the 1961-2 contest against Igwe Enwezor (and others). The palace complex, at left, remained basically in the condition it had suffered when, after the Obi and his supporters had been forced to flee Onitsha, Nigerian Federal troops demolished it during the Biafra Civil War.

But across the street (and behind it, at left) the Onyejekwe family had built a new house (appearing of similar vintage to Aniweta’s mansion previously shown). The Onyejekwe family thus remained a center for his Ogbe-ozala lineage. (I did not find time to arrange a visit with the family.)

From Okwu-eze looking soutwest into Ogbe-ndida Village, one could see a large building labelled “Word of Life: Mission Inter[national?] under construction. Someone was apparently occupying it, but it was far from ready for a congregation of any size. An array of thatched buidlings (perhaps to accommodate diners?) was located next door.

Reuniting with T. C. Ikemefuna, now an Ozo man

It felt very good for me to see my old mentor again. Unlike most of my Onitsha friends, we had stayed in periodic contact since 1962, for example he sent me a pair of woven tiny caps when my sons were born in 1969. There was an abiding fondness at root.

We sat down for some drink in his parlor. I was struck by the complete absence of any “idols” — traditional Onitsha spiritual figurings that had been so close to him in everyday 1962. (Oddly, I did not ask him about this during our visits — I am unsure why. So much information was passing by, and my “plans for questioning” (anthropological basics) remained unformed.

He hadd sent me this picture of him engaged in his Ozo title procession. Somehow I had failed to notice an obvious change in this image: none of the marchers were carrying Ossissi, the spiritual connector of Ndi-Ozo with their ancestors. The Ôssissi — a central signal of the Ozo man’s presence — were gone from the ritual scene.

Ikena had been enabled to take the title by his son (whom I had briefly encountered in 1961, then a young boy), who was now “in pharmaceuticals”, and had acquired enough wealth to finance the title for Ikena as well as another close kinsman (or two? — I didn’t record carefully — very substantial monetary giftings in any case). The young man now insisted — rejecting my expressed desire to drink some fresh palm wine with Ikena — that he treat me to a luncheon at a suitable, European-style restaurant. This we did, to my deep chagrin — it seemed there was no denying the voice of this younger man’s authority in the current situation of his (Umu-Orezeabo) descent group.

My good fortune to meet with Okunwa T. B. Akpom’s Daughter!

I’m unsure how this was arranged, but I managed to meet again with Christiana Egbuna (wife of the eminent House Speaker Egbuna) and her daughters.

T.B. Akpom was recommended to me by the eminent Onitsha lawyer Chuba Ikpeazu, and he became my closest approximation to a beloved parental figure in Onitsha from 1960-62.

Readers will find him repeatedly active in the chapters here entitled “Sought but not Seen”. I managed to get a good photograph of him with Christiana during the Obiship contest in 1961 (the evening of “Voting no-confidence in Onowu”), but somehow this very fine picture was lost. (I think I lost about three such priceless images during the years I gave lectures doing slide-shows. These were hazardous efforts in that regard.)

When I entered her house (I think somewhere in the former “European Quarters” of Onitsha), she was listening to a very interesting program on the BBC. I don’t remember the content of our visit otherwise, but still feel a very strong warmth when recalling her and her family members.

Recovery, renewal at Uno-Nkisi-Aroli

Helen prepares to leave St. Charles Borromeo, her ankle safely wrapped in a plaster cast. The Night of the Fall seems remote at this point, but many plans have changed: we now prepare for an early depaarture for further medical procedeures in the U.S.A. (One persistent probglem: the local banks refuse to honor our American Express credit card — only Thomas Cook will do.)

Here Helen makes use of our Nkisi-Aroli sofa to enjoy a bottle of Star-beer (one of our 1960s favorites, still extant 30 years later). We began receiving visitors, as we also began figuring out how we could begin arranging further medical treatments “back in the U.S.A.” ASAP..

Nneka’s ‘younger sister Emengini did our cooking for us — delicious food.

The Status of Shrines and “Ilo” (Village squares) in Enu-Onicha

When I saw standing buildings that clearly had “shrine” status, I went to explore them if I could. This one, located in Umu-Aroli, was in an advanced state of disrepair but still “present”, so I proceeded to look inside.

Hard to see, but this was clearly an Onitsha-style Ikenga — a personal ritual object denoting one’s condition of (and aspirations for) achievement within the community. These were sometimes retained by immediate descendants , after a person died. This one had at some time been given blood sacrifice, but that was loong ago judging by the absence of evident blood staining beyond the somewhat darkened coloring.

Here, a row of Okwachi (icon of the personal self of an Ozo-titled man), Ossissi (the staves of titled men) and Okpulukpu (homes of Ozo-titled ancestors, to be given regular blood sacrifice) stand only slightly protected from the destructive forces of time. They entirely lack evidence of recent use.

Here is a closeup of a set of Okpulukpu. This entire array indicates that these formerly active, pivotal icons have been discarded. Apparently, the owners did not want actively to destroy them, but they have been definitely set aside, one would presume to decay over time, eventually to disappear by naatural erosion.

From this experience — and also my visit to the Utoh shrine in Umu-Asele Village — I concluded that the use of these ritual objects in the traditional forms of animal-sacrificing religion among Ndi-Onicha had undergone a definitive — one may say total — decline. John Christian Taylor (the first Onitsha-resident missionary, a Sierra Leone repatriated slave known for his sometimes excessive enthusiasms), asserted with confidence in Onitsha in 1859, that “the Idols are now tottering, and I hope will be ere long for ever paralyzed”” — a prediction that appears to have finally occurred (130 years later). Paralysis seems a suitable metaphor.

What did apparently remain were the “Ani” — Mother Earth — trees marking the locations of different Village Squares, at least those of major villages. For example,

At left, the Egbo tree marking Ilo-Umuasele (the ritual “square” of Umuasele Village) stands beside the Utoh shrine building. The latter, once also an important ritual focus for Umuasele, is falling into decay (like the one at Umuaroli, above) with old ritual objects inside it gradually falling apart, but the tree marking the assembly place for the village remains standing, gathering size.

I also found this true at a point of major opposition between villages. the Ani-Umuezearoli remained a massive grove of trees, while directly across the street from it stands Ani-Ogbeabu, the tree complex marking the focus of that major village. These two major villages stood of course in major conflict over the issue of kingship in both 1900 and 1931-35, and the opposition remains politically relevent. So where trees mark the presence of major villages, they perhaps remain visual markers where issues of land rights may arise.

Ndi-Onicha and Technologies

In 196o-62 we saw little indication of economic production within the Inland Town of Onitsha. Ndi-Onicha did little basic production (aside from growing small kitchen-gardens and keeping a few goats). There were a few traditional marketplaces organized by local women, a few palmwine bars, but almost no shops.

At left, a view indicating the vast expanse of the palace grounds of Obi Okosi II on the day when crowds gathered for his funeral in 1961. Frank drove me by this location in 1992 at my request. We saw that the entire space had become a motor-repair park, full of vehicles in various states of disfunction. I wanted to photograph the scene, but Frank forbade it as “dangerous” to do.

I then asked him to drive me past the Onitsha Main Market. This he adamantly refused to do, saying it was “very dangerous” to attempt. I didn’t inquire much further about this, but it appeared that Ndi-Onicha were doing their dealings elsewhere. The sense of ear was surprising.

My interest in evolving technologies in Onitsha led me to ask Frank to show me what was happening along Awka Road. (I remembered the prominence of Awka blacksmiths in the early 1960s.) He did this, and visually what struck my eye was repeated arrays of what I called “bombastic gateways” presented for sale, presumably designed as facades for the entryways to homes of the super-rich living in the towns near Onitsha. We saw quite a number of more or less similar forms.

But the fact was that my persisting focus on this portion of Awka Road in the center of Onitsha was an error of historical fixation. Much more intensive activity was happening on the other side of town.

Observe the 1957 center of Fegge, the squared-streets subdivision on the southern side of town. “Nupe Square” marks its center. The nearly-horizontal east-west street across its southern edge, “Port Harcourt Road”, In 1962 really marked the southern edge of Onitsha town. Below it to the south was farmland.

Byron Maduegbuna took me down there sometime in 1961, during the time of Onitsha-Obosi violent conflicts in late 1960. He wanted to show me (and did so in fact) the locations of what was once called Aboutshi Whorf, where after the British bombardment of Onitsha in 1857 the Europeans relocated their trade and mission efforts, and where a number of graves marked how deaths due to “iba” (malaria) had cut down a number of missionaries at that time.

We were accosted by some Obosi people there and Byron had to respond to them in the Obosi dialect of Igbo in order to pass us by freely.

My simple point here is that in the early 1960s this entire area was farmland. But the Niger Bridge was coming, and it did come shortly afterward, in 1965. The social and economic transformation of this area — tranquilly occupied by the Aboh-related residents who called themselves “Ogbe-ukwu” (“Great Village”) in 1960 — began immediately.

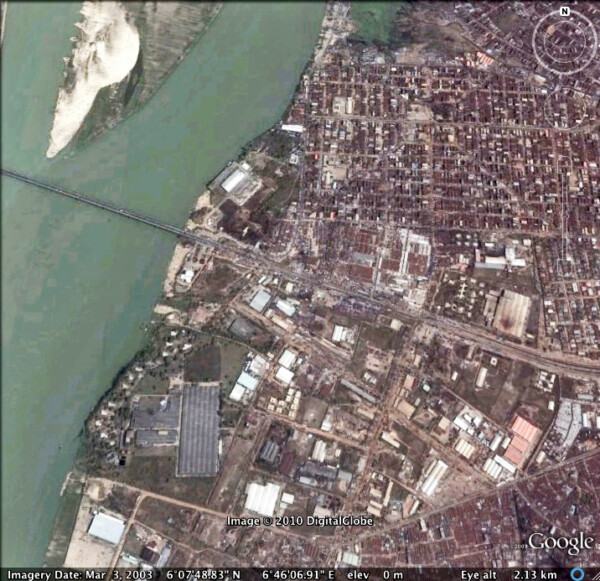

At left, a narrow view of the area which I gleaned from Google Earth in 2003. Immediately south of Pt. Harcourt Road, intensive development has obviously occurred, and further south of the new highway much more substantial business proliferation has also emerged. This was part of the general area where Frank took me to find Helen’s high-quality crutches, and as we passed through innumerable arrays of stalls I could see that high-quality material of wondrous variety were available. Too bad it was that Helen and I had to struggle to acquire enough negotiable funds to make our way back to the U.S.A., given our own economically-naive problems with getting American Express working for us in Onitsha.

Everpresent Jesus

Everywhere we went, we encountered Jesus. I did not obtain many images, but the amount of attention paid to this figure was strikingly more evident than it had been in the 1960s (when it was present enough). I was particularly struck when, during an interview with a senior Onitsha elder, one of his wives seated nearby kept humming and sometimes voicing Christian hymns, smiling peacefully, yet defiant.

The man showed his irritation slightly but did not speak out. Even more striking was the behavior of one of the youths close to Nneka’s family. Several of them seemed to be hanging around without much to do, and Nneka was constantly warning them not to sneak around and steal any of the Henderson belongings. I sought to engage one of them, asking how things were going, and he said after a while that he felt pretty hopeless, commenting “We need a Savior!” I had heard nothing like this during the 1960s. Actively yearning for a Savior cannot be a very healthful condition.

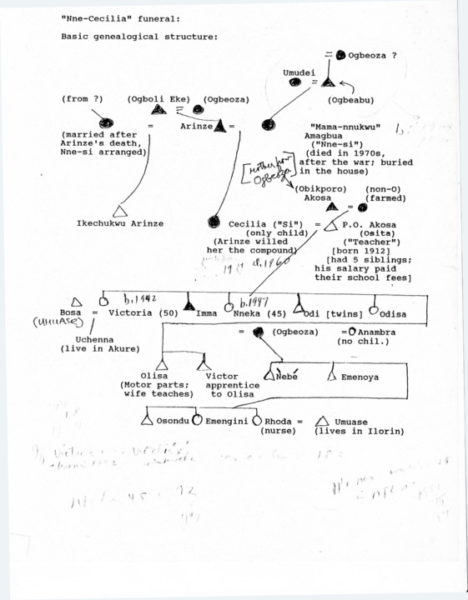

The (long-postponed) Funeral of Nne-Cecilia

Above, see the elaborate genealogy of Nne-Ci, a distant grandmother of Nneka Umunna, related to her through both maternal and paternal ascending links. An enactment of this ancestress’s long-delayed funeral, to be done with video camera, was an integral part of our original research plan. Despite Helen’s disastrous collapse, on the scene, we actually did manage to organize and record the events of this very brief funeral. Later, in 2000, we visited Nneka in Jacksonville while her sister Veronica (who had participated in the event) was visiting Nneka, and went over the video with her and obtained further details.

This project was part of Helen’s planned further research, but unfortunately the plan fell apart due to her onset of Alzheimer’ and so it was never completed.

- see the article published in 1988 by myself and the late Ifekandu Umunna in the bibliography of this website [↩]

- Compare the similar figure seen beside the entry to Igwe Enwezor’s palace, further below on this page. [↩]

- My Nigerian Spokesman newspapers, sent me in 1963-66, elaborately documented Obiekwe’s eventual analysis and dismissal of the Igwe’s candidacy. [↩]

- The reader will encounter Igwe Enwezor in various portions of Chapters Four and Five of this website/volume. He was an extremely prominent figure during the “Sought But Not Seen” phase of the 1960-2Interregnum. [↩]

- His defection from the Enwezor Obiship-promoting camp became complete in 1964-5: see the Nigerian Spokesman reporting in that earlier section of the present Chapter. [↩]