[Note: Click on any image you may want to enlarge.]

[Note: Click on any image you may want to enlarge.]

1. Umato in Umuase: Byron Interrupts

On the morning of August 26, 1961 (while the Royal Clan Conference is preparing for its meeting to make the “Announcement of Obi of Onitsha” described in the previous page), I read in the Spokesman that “E.N. Nzekwu Omodi the head of all Umu-Ase-Iyawu… will celebrate the Umato feast today in his Oguta Road residence.” Since it is part of my research plan to attend the major seasonal rituals in Onitsha, and since I prefer appearing in those events not too much identified with either Interregnum faction, I speak with Mike Agbakoba, a University College (Ibadan) student who belongs to Umu-Ase, and who is working with me during his school vacation. He arranges for us to attend the event together.

Mike escorts me in the late afternoon to the home of the Omodi, a very important member of the Ndichie-Okwa (“Throne Chiefs”) who has additional political prominence in Enu-Onicha because he holds the ascriptive right to the status of Eze-Idi “(“Hidden King”) in his section of the non-royal clans.

When we arrive at Nzekwu Omodi‘s compound, a crowd of more than a hundred children and youths cluster around the porch of the main house. Mike says that one of the most eagerly anticipated occasions of his childhood was this kind of seasonal festival, where the elders themselves seldom eat much of the bountifully presented food but call their children, one by one, to come and be given a share. The young people are awaiting this outcome of the ritual, which is now being undertaken largely beyond their view, inside the building.

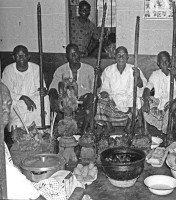

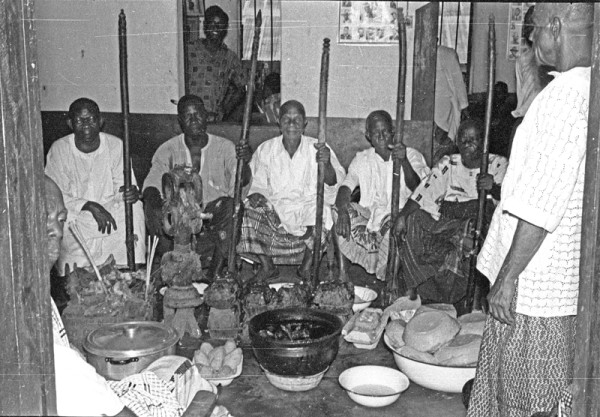

The interior contains first an anteroom and then the Omodi‘s court room, a long rectangular expanse which we enter through a central door, to find ourselves facing the five senior lineage priests (Diokpala) of the major segments of Umu-Ase-Iyawu, who are seated before numerous enamelware bowls heaped with pounded nni- oka (“Corn Food”, the traditional offering of this first Harvest Festival of the year) and holding their Ozo Title staves.

Dressed in a pure white gown, the Omodi sits at far left of the row (from his perspective, on the far right of his fellow priests), confronting a huge ikenga statue1 that symbolizes the ram-horned Spirit of the Ogbo Family whom the Omodi represents. The Omodi’s personal Okwachi (Vessel of God) is also on display, since he is the host for this ceremony.

Beyond the place of the fifth senior priest, a row of Ozo men sit in a curving line which leads back across the near side of the room and ends with other Umu-Ase-Iyawu chiefs (Asagwali, then Odua) and at the far left of the room Anatogu the Onowu, who sits facing down the room’s full length. He too wears white, but holds only his leather fan and a horse tail whisk in his lap.

The Prime Minister is also a member of Ogbo Family (a lineage of exceptional prominence in Umu-Ase both because they are the large landowners who have recently defeated the Obosi people in their appeal to the British Privy Council, and because the Ogbo family claims the sole right to provide the senior priest of the clan). The Onowu and the Omodi are the two strongest poles of Umu-Ase power in Onitsha Inland Town, and being closely related they have long worked cooperatively, often in opposition to the entire Royal Clan.

We watch the ritual from the anteroom, through one of the numerous open bay windows provided for spectators on the court room’s two sides. The senior priest presents each of the types of drink and food to the ancestral ghosts, then serves first the Prime  Minister (who immediately calls his own grown-up sons to receive portions), then the other chiefs and the five senior priests (who do the same). In due course Mike Agbakoba and I are given our shares, and while we are eating we overhear one titled man chiding the Asagwali (an Onye-Ichie-OkwaraEze), saying “Why do you and other chiefs support Enwezor? He is not the popular choice.” We also hear some of the youths in an anteroom discussing the kingship, and one youth of about 20 says, “all the young men support Onyejekwe.”

Minister (who immediately calls his own grown-up sons to receive portions), then the other chiefs and the five senior priests (who do the same). In due course Mike Agbakoba and I are given our shares, and while we are eating we overhear one titled man chiding the Asagwali (an Onye-Ichie-OkwaraEze), saying “Why do you and other chiefs support Enwezor? He is not the popular choice.” We also hear some of the youths in an anteroom discussing the kingship, and one youth of about 20 says, “all the young men support Onyejekwe.”

Then, as we are eating our corn-food soup, Byron Maduegbuna and another member of the Royal Clan Conference Special Committee (which had presented Onyejekwe to “the people” earlier in the same afternoon) arrives at the compound by taxi and walks into the house. Holding a letter, Byron removes his hat, enters the reception room, and kneelst before the Onowu to beg a moment of his time, as the five senior priests watch them.

The Onowu cuts him short: “Why do you come in here, when I am sitting in the presence of the Ndi-Mmuo (Ancestral Ghosts), to make trouble? I am busy. Get out of here.” Byron promptly leaves without complaint, but outside he remarks to me, “We will return tonight.”

2. August 27: the Prime Minister calls all Ndichie

The Onowu convenesd a meeting of the chiefs and reads to them the submitted Royal Clan Conference letter, which demands that the chiefs receive and accept Onyejekwe on the 4th of September. In this meeting of the Ndichie (the sole verbal account of which I hear from the Ajie and it is no doubt strongly biased), the Odu presents in response his own document, a Proclamation for the chiefs to sign that they herewith install Enwezor as Obi, and (says the Ajie) “at last, the chiefs revolted from being led by the nose by the Odu and Onowu.” Okolonji, the Akpe, a close Odoje lineage-mate mate to the Odu but recently estranged from him, questions the Prime Minister about his new refrigerator and (confronted with the Onowu‘s denial of its rumored source) warns him that the youths are now investigating the issue of its purchase. He also turns on the Owelle and asks him how the latter has suddenly managed to pay for such things as having a telephone installed in his newly-finished house. The Akpe concludes by accusing both Senior Chiefs of supporting “an unpopular man” for money, and accuses the Odu of doing the same because he and Enwezor are both Freemasons.

The Ajie‘s version of the outcome of this meeting is that it ended “in confusion,” and whatever actually did occur, the chiefs excise any reference to it from their formal records. These records (later submitted at the 1962 Harding Commission of Inquiry, see that page at the end of this Chapter)) did describe a meeting two days later, on August 29 (whose minutes are not confirmed until November 21) in which the Onowu re emphasizes Umu-EzeAroli support for Enwezor, but (so it is recorded in their meeting minutes) the chiefs agreed to convene a meeting with the Royal Clan Conference Special Committee to receive the presentation of Onyejekwe to their group.2

On August 31, the Secretary of the Royal Clan Conference sends a formal letter of notification to the Chief Secretary of the Premier of Eastern Nigeria, stating that “Umu-EezeChima Family (Kingmakers) have unanimously selected Mr. Joseph Okwudili Onyejekwe as the Obi elect….” On the following day, they go to the Onowu‘s house to present their candidate to the chiefs.

Anticipating trouble, the Royal Clan Committeemen plan their counterarguments beforehand, and (anticipating success) they bring along Nnanyelugo Melifonwu (senior priest both of Isiokwe and of Umu-Chima-Ogbuefi, clad in white cloth and ready to perform the Ima-Nzu painting ritual if that proves appropriate. Their candidate, Nnanyelugo Onyejekwe, comes also (dressed in white), and now is accompanied by former dabbler-candidate Akunne Ediboss, who as a fellow Ogbe-Ozala elder has now attached himself firmly to Onyejekwe as a cultural advisor (and potential bodyguard). As they enter the Prime Minister’s compound, the Onowu‘s wife (who, as a newly-reconciled Daughter of Enwezor’s Umu-Anyo, has become a strong supporter of Enwezor) verbally accosts them. The entourage however keeps their silence and takes their place in Onowu‘s reception hall.

As the assembled chiefs sit before them, the Committee representatives present their man. Committee Chairman Okunwa Akpom speaks at length, describing the procedures and accomplishments of the Special Committee, and concludes with an account of the entire Royal Clan Conference selection process (including the fact that one of the candidates actually “stepped down in the interests of peace”). Then candidate Onyejekwe briefly addresses the chiefs. After Onyejekwe has spoken, the Onowu asks if there are comments from the other chiefs. Only the Odu speaks, asking which candidate had stepped down. Otherwise there is silence, and instead of the usual ending to meetings of this type, where the chiefs rise singly and depart in descending order of precedence, the chiefs walk out en masse. Only the Prime Minister’s wife waits to derogate the Special Committee and their candidate as they follow suit in departing.

Afterwards, the Committeemen meets with Onyejekwe, expressing surprise at their uncontentious reception at the hands of the chiefs. None of Enwezor’s supporting group has been present, and the chiefs offered no aggressive response. The Special Committee is told that Okolonji Akpe, the chief who criticized the Prime Minister at the earlier meeting, had threatened to repeat his questions at this meeting, but he said nothing; perhaps his threat had silenced the voices of the others. One elder suggests that the two very prominent lawyers of the Prime Minister’s own Ogbo Family, Moses Balonwu and C.E. Agbu3, have warned him against hasty action in light of the “critical Paragraph Six” of O’Connor’s 1935 Memorandum, which purportedly relegates the role of the chiefs to a “mere formality.”

Onyejekwe then asks the members how much the installation procedure would cost him. They estimated about £2,000, including the major feature of six cows to be killed (one for each of the “six major villages” of Onitsha), an additional one cow for going for the ritual at Ije-Udo, and one for the return from that shrine, and one cow for the Ikporo-Onicha (Women of Onitsha).4

Onyejekwe will, they agree, also have to purchase all of his regalia5. Many new items will have to be acquired, including a substitute for the Anazonwu Royal Ofo ((There is said to be such general fear of the existing one that people have decided it should be placed in a museum somewhere, but also it is not available to their grasp even should anyone muster the courage to do so.)), and he must provide feasts for the non-royal clans before they will bestow the “Anvil Ofo” (Ofo Otutu) upon him.

When we later ask Byron about details of the ritual procedures, his response suggests the Committee is discussing alternative plans. For example, when Helen asks him when the Obi-elect will go to the Onowu‘s compound to do domestic services for the Prime Minister, Byron denies that this is the custom and says it would never be done. The domestic services will be performed at Udo, he says, and the Onowu will merely bow to Onyejekwe after he has been carried shoulder-high to his home. While my own understanding of the installation sequence is incomplete, I know this would be a very substantial innovation, obviously intended to reduce the Prime Minister’s role to a bare minimum.

3. Newspapers discuss the Selection

On August 30 the Spokesman prints an article entitled “Obi elect of Onitsha” (under the authorship of the Ajie), which outlines the work of the Royal Clan Conference’s Special Committee, gives specific thanks to each of its members, and calls for unification of the whole community under the new Obi. In the same issue an editorial headlined “Congrats, Onyejekwe,” reports that

“The Umu Eze Chima (King makers) have chosen Mr. Joseph Okwudili Onyejekwe as their candidate, out of the eight contestants. The method of selection was most democratic and we have no doubt that the Onowu of Onitsha will have no difficulty in presenting him to the people of Onitsha.

We don’t intend this morning to discuss his rivals, all of whom have graciously accepted the verdict of the Umu Eze Chima who are the right and proper family to select an Obi (according to paragraph 6 of the O’Connor Memorandum).”

On the same date the Observer provides a banner headline:

SPIRITUAL HEAD OF EZE CHIME (sic) KICKS

“Onyejekwe’s Selection not Constitutional”

and the accompanying article reports that Mr. A.O. Agunyego, the Spiritual Head of Umu-EzeChima family, states that no selection by this family “would be constitutional and genuine unless it has my support.”

On the first of September the Observer reports that a telegram has been sent by “the Secretary of the Umu-EzeAroli family, Mr. Obiekwe Aniweta,” to the Managing Director of the Zik Group of Newspapers, demanding that the Editor of the Nigerian Spokesman be immediately removed from office for “suppressing articles in support of the candidate of Umu-EzeAroli..,” and on the following day the Observer publishes a release by Aniweta warning the Editor of the Spokesman against “distort(ing) the history of Onitsha in order to satisfy certain individuals.” Obiekwe claims that this “senseless and tactless editorial” (of August 30) is “committing the Press to a policy of aggression against the candidate popularly selected as the Obi elect by the entire people of Umu-EzeAroli whose turn it is to supply the next Obi of Onitsha in compliance with the recommendation contained in the great document of 1935.”

In reply on the 4th the Spokesman runs a brief statement by the Prime Minister together with a now more neutral editorial, both stating that of nine candidates for the throne the number had now been reduced to two. On the 14th it prints articles by the opposing sides. For Enwezor, Aniweta argued “that the only King Makers of Onitsha are the Red Cap Chiefs,” and accused “the so called Umuezechima Association” of introducting “apartheid” into the contest by stipulating that the mother of any Onitsha King “must be an Onitsha Ibo i.e. must not be a non-Onitsha Ibo or any other outsider.” Speaking for Onyejekwe’s side, four prominent Ozo-titled men of Umu-EzeAroli (including Moses Odita and 3 other leaders of Ogbe-Ozala) present a signed statement which emphasizes “that only the Umu-EzeChima have the right to select an Obi,” that the August 10 meeting of Umu-EzeAroli had directed the Onya to submit the 7 candidates from that group to the Umu-EzeChima, and points out that within the Umu-EzeAroli, substantial numbers of people representing various named segments of the subclan have supported various candidates other than Enwezor. “How then” (the article concluded) “could it be said that Umuezearoli UNANIMOUSLY support Mr. J.J. Enwezor’s candidature”, as has been stated in the newspapers and radio accounts of August 21 and 22; the fact is that “only a fraction of Umu-EzeAroli support J.J. Enwezo, and this fraction of Umu-EzeAroli is only a very small fraction of Umu-EzeChima, King makers of Onitsha.”

Then, on September 16, the Spokesman begins publishing the full text of the much-cited (but apparently by most Onitsha people, not previously read) O’Connor Memorandum, running it in four installments over successive days. For the first time most literate Onitsha people are able to read this historic document verbatim, rather than grasping its import mainly by hearsay. While it would be out of place to present a full discussion of this document here, a few comments are relevant.

The O’Connor Memorandum of 1935

Captain O’Connor appears to have had a fair working knowledge of Onitsha history and custom, but from a contemporary anthropological perspective it is apparent that his main purpose in writing the 1935 Memorandum was not to reconstruct the most probable history but rather (aside from justifying the selection by Government of James Okosi as the new Obi) to formulate a model of royal succession suitable to a Colonial Government bent on introducing some changes into what was then called the Onitsha Native Authority Council5.

For our present interests the two most salient portions of the Memorandum are paragraphs 4 and 6. Paragraph 4 states that the Obi came only from

“Umu-EzeChima in direct descent from Oreze whence there sprung the three ‘kingly’ units of Umu-Dei, Umu-EzeAroli, and Obikporo.6 In actual fact the last named though having the right to give an Obi to the town has never yet done so.”7

O’Connor then observed that

“In theory and doubtless it was originally intended succession was meant to alternate between the families or units concerned and in default of Obikporo supplying an Obi, between Umu-Dei and Umu-EzeAroli. In actual fact that has not obtained.”

He concluded the paragraph by noting that “Had there been a strict alternation there is no doubt that much of the disputes of today would have been avoided.”

The historical evidence eventually available to me suggested that no single “theory” or model for succession had ever become accepted by all sections of the royal clan (though the early missionary accounts from the 1870s, reporting on the Interregnum that began in 1872, assumed a very different succession process than the one just outlined). O’Connor chose to present that version which would result in a rotation between the two largest subclans of the Umu-EzeChima, and thus distribute access to royal power more broadly and its periodic transfer in a more orderly fashion.8

The pivotal paragraph 6 of the Memorandum was printed in the Spokesman in enlarged type:

“6. Upon the death of an Obi candidates were put forward by the families whence an Obi could come. Those to put it briefly were subject to an examination by the Umu-EzeChima, upon the heads of whom devolved the duty of an ultimate selection. Having arrived at a selection the heads of Umu-EzeChima presented the future Obi to the Ndichie for acceptance. This acceptance was presumably purely formal and the next step would have been the presentation to the Obi elect of the royal Ofo.”

The “presumably formal” acceptance by the chiefs was a normative standard imposed by O’Connor on a political system whose traditional rules (as I later came to see them) were to some extent mutually contradictory and were being sharply contested in precolonial times, but certainly such a diminution of chiefs’ roles had no precedence in any known past. Indeed, O’Connor proceeded to contradict his own model of peaceful succession in paragraph 10 of the Memorandum, stating that “a combination of force and wealth settled this sort of thing in the past”, when “The appointment of a new Obi was usually a matter of a coup d’etat, whereby the people of Onitsha were presented with an accomplished fact before any countermeasures could be taken.”

All this would imply quite potent roles indeed for the chiefs, but O’Connor elsewhere suggested that Onitsha people in 1935 had become very distrustful of the Interregnum activities of chiefs (especially the senior chiefs), and the procedure he formulated here would in effect serve nicely to inhibit them.

Paragraph 6 concluded with a discussion of the Royal Ofo, suggesting that “it is probable that the right to confer the Ofo was vested in the Onowu who normally would have been of the division Ugwu-NaObamkpa, a non royal clan.” Again, both of these normative standards were non-traditional impositions by O’Connor, and (when combined with the rules just discussed) they would also serve to distribute power more broadly within the community than obtained at many times in the past.

Whatever their original “truth” status, O’Connor’s findings are now being examined by Onitsha people in 1961 as a prime authoritative source of normative precedent, and the Spokesman‘s emphasizing of paragraph 6 suggests which particular precedents its editor finds most compelling: namely, those tending to democratize the interregnum process.

In contrast and fully three weeks later the Observer publishes a series of articles by its resident intellectual, S. W. Nee Ankrah (a non-Onitsha, indeed a non-Igbo man), which cites the O’Connor Memorandum with a different selectivity for its suggested dual rotation between Oke-BuNabo and Umu-EzeAroli and then emphasizes the February meeting of the latter group in which Enwezor had won by secret ballot. Turning then to the issue of who has the right to proclaim an Obi, the author discards O’Connor and turns-instead to C.K. Meek’s Law and Authority in a Nigerian Tribe, citing Meek’s statement that in Onitsha

“The general body of the populace had no say in the matter (of royal succession) except in cases where disputes over the kingship led to civil war. But it was usual for the candidate to secure the goodwill of as many of the Ndichie as possible.”

Having made this point of non-democratic, aristocratic procedures, Nee Ankrah then returns to O’Connor to cite evidence concerning the role of the Onowu during the 1931 35 interregnum. Then Prime Minister Gbasiuzo Okosi, who was Obi James Okosi II’s father’s brother, endorsed his brother’s son as Obi-elect at that time, and the O’Connor Memorandum described at several points his stubborn refusal to withdraw this support in favor of an Umu-EzeAroli candidate, claiming that he as Prime Minister had the sole right of installation and “he had already installed James Okosi.” The subsequent victory of Okosi II in 1935 could be read as sustaining this view.

From this evidence, Nee Ankrah draws the conclusion that “the appointment and installation of Obis had always been the sole responsibility of Onowu (with his red cap chiefs, Ndichies) and not in any shape or form an affair of the Umu-EzeChima.” After discussing the “qualities and attributes” of a good ruler, (emphasizing the “sociable, unassuming, amiable, sagacious, generous, and philanthropic”), and insisting that “a successful and good ruler need not necessarily be an academician!”, the article ends with a call for the Prime Minister and his chiefs to meet and make their decision, for “they and only they are the king makers!”

This Observer author’s use of Meek’s perspective is ethnographically insightful and (since Meek’s book was not, in contrast to O’Connor’s Memorandum, written in a social context directly addressing restructuring Onitsha society in light of the current Interregnum) might well lead a disinterested analyst to the conclusion that the O’Connor Memorandum contained serious factual and evaluative errors. An interesting feature of the Observer article, however, is its tendency to conceive the opposition between the “chiefs” and the “Royal Clan” as absolute, as though leadership must fall either to one or the other. While the social role of a chief and that of clan member might indeed come into conflict (as we shall shortly see), a fact always to be remembered is that a majority of the chiefs are themselves members of Umu-EzeChima, and therefore some chiefs would inevitably be involved in leading any mobilization of this very large social group. Whether a particular chief is a member of the Royal Clan or not is thus a highly relevant fact, strongly conditioning the extent of his influence in the succession dispute.

That there was apparent confusion concerning this point became evident to me when I discussed the 1931-35 interregnum with Douglas Molokwu (while he was working in the Special Committee’s research). Comparing the role of Anatogu, the current Prime Minister, with that of Gbasiuzo the Onowu in 1931 35, Molokwu said,

“(The present) Onowu has forgotten he is an Ugwu-NaObamkpa man, hence he can’t use all the powers of Gbasiuzo Onowu. Gbasiuzo could do everything because he was Umu-EzeChima.”

From this point of view, of course, senior chiefs from the Royal Clan would be expected to have a much more decisive role in Interregnum than do those from non- royal clans, and in the current episode this would of course forefront the Ajie rather than the Onowu (and viewed from the perspective of Royal Clan Senior Chiefs’ commitments, the lineup was 2 vs. 2, with seniority advantage to the Conference side).

4. Non-royal Clans Confront the Conference

Early in September, now, the Prime Minister meets with some people of his own major village, the Umu-Ase-Iyawu , a major unit of Ugwu-NaObamkpa (the covering term often used to refer to “the non-royal clans”, though not quite encompassing all of them) and the one traditionally charged with bestowing upon the new King his Royal “Anvil Ofo” (though the original is now out of reach somewhere in the bowels of Umu-EzeAroli, perhaps in ghostly clutches of its last known holder, Obiozo Anazonwu, the late Onya.). The Onowu shows them the Special Committee’s Report, and points out that some of the Report’s recommendations adversely affect the Umu-Ase-Iyawu. Members of the village become alarmed, and agree to the Onowu’s proposal to call a meeting of all Ugwu-NaObamkpa for September 14 to discuss the matter. On September 12 the Secretary of Umu-Ase-Iyawu, R.D. Agbakoba, writes a letter to the Chairman of the Royal Clan Conference stating that the Special Committee’s Report deals with matters directly affecting their own non royal village, and attacking its contents on a number of specific points. including:

“5) That paragraphs 12 and 18 of the said document deal with matters which are in no way the concern of the Umu-EzeChima family. That all matters about the “OFO” can only be dealt with by Umu-Ase-Iyawo and the Obi elect, and that they regard the recommendation made by the Committee and your adoption of the recommendation as an intrusion, or rather an invasion of their rights.”

Paragraph 12 in the Special Committee’s report discusses their efforts to restore the original Anvil Ofo while paragraph 18 suggests that “the Ofo should be handed over to (the Obi-elect) by Ugwu-NaObamkpa family for whom food and drinks should be provided….” According to oral traditions not examined by the Committee, prior to 1900 the control of the Ofo had been vested not in Ugwu-NaObamkpa as a whole but in Umu-Ase in particular, more specifically in the senior priest of Ogbaba family within that descent group.9 The Report’s findings in these two paragraphs thus reflect an outsider-group’s oversimplification of the structure of another, and was indeed an intrusion into a complex of rights concerning which the Umu-Ase would necessarily participate.

The letter continued:

“6) That paragraphs 19, 20, and 21 and the whole of Appendix A of the document are matters which can be dealt with by all Onitsha people and not by Umu-EzeChima family alone who are only a part of Onitsha.”

The paragraphs cited refer to the ritual steps to be taken by the Obi- elect as he proceeds to gain legitimacy with all clans of Onitsha, while Appendix A is the list of “conditions to be satisfied” by prospective candidates. All of these matters could of course be viewed as issues about which the whole community (and its various segments) should have rights to decide, not merely the members of the Royal Clan. This assertion implies a strongly democratic bias.

“7) That the recommendations contained in Appendix “B” of the document are entirely misconceived because the Committee started with the assumption that Umu-EzeChima family are on the same category with Ogbo-Isato (The Eight Age-Grades), an assumption which is entirely wrong, because the former are members of only a family in Onitsha, and the latter represent the whole of Onitsha and could therefore speak for the whole of Onitsha.”

Appendix “B”, the “Rules Governing the Obi of Onitsha”, juxtapose the recommendations of the Ogbo-Isato with those of the Royal Clan Conference’s Special Committee, proposing to institute a set of councillors (the Uloko-Obi ) and (in Rule 5) the new rotation system between “Dei” and “Umu-ChimaOgbuefi.” Technically this criticism errs with regard to rule 5 (which presumably would be a matter for only Umu-EzeChima to decide), but otherwise the logic is telling (the Age Grades sets do not discriminate between Royal and non royal members, and the “Eyes of the King” (Uloko-Obi) as a new kind of royal advising committee would presumably also include non royals).

“8) That they deplore especially the Committee’s recommendation in paragraph 3 of Appendix B which entirely disregarded the recommendation of the Ogbo-Isato on the matter and paragraphs 12 and 25 of (the O’Connor) Memorandum….”

Paragraph 3 in the Appendix refers to procedures for selecting Senior Chiefs, recommending the King consider advice from both the proposed Uloko-Obi and the existing senior chiefs. Paragraph 4, which is linked with it, recommends that the office of Onowu “must not be given to any quarter in Onitsha from where the reigning Obi originates.” This portion of the Umu-Ase-Iyawo letter no doubt points to both of these issues; paragraphs 12 and 25 of the O’Connor Memorandum dealt specifically with dissatisfaction arising over the fact that King Samuel Okosi appointed “his blood brother to be the Onowu“, stated that “It is more likely to assume that the Onowu should have come from Ugwu-NaObamkpa thus ensuring that at no time could this eventuality arise…”, and reported that at a meeting of all the Onitsha chiefs “a proposal that in future the Onowu should be appointed from Ugwu-NaObamkpa… met with general approval….” This issue of power allocation to the non royal clans had in fact been a burning one for many decades in Onitsha, and from 1944 to 1958 Okosi I’s failure to confer the title to a member of Ugwu-NaObamkpa (as he had earlier promised in writing) had been sanctioned by a formal boycott of the palace by that group.

This portion of the Children of Ase letter thus nicely exposes one of the main chauvinistic goals shared by the members of the Royal Clan Conference (and which had been manipulated in their early meetings by the Orator Spokesman aiming to generate Conference solidarity): to maximize the rights of the Royal Clan at the expense of the non-royal clans. The subsequent paragraphs of the Umu-Ase-Iyawu letter repeatedly emphasize this point, including the statement that “…matters can be easily settled in this town if all the families will respect each others’ rights and feelings and realise that this town is built on equality of the families therein….”

5. The Conference Makes a Conciliatory Response

Through their intelligence network, members of the Royal Clan Conference gather that a former participant in the Special Committee (possessing his inside knowledge of the Special Committee’s proceedings, but now working against it) has pointed out to the Prime Minister that the report was vulnerable in these areas, and they believe the Onowu was directly behind this move of Umu-Ase-Iyawo. They are convinced he is now irrevocably committed to Enwezor’s side. One member reports a rumor that the Onowu had actually been required, when he allegedly accepted decisive gifts from Enwezor, to take an Oath (iyi) on the Black Juju (Iyi oji, the dreaded Spirit from Nkwele town) that he would give the candidate from Umu-Anyo his eternal support.

The Conference leadership however chooses to set aside questions of blame and moves swiftly to make a strongly conciliatory response, replying in a letter of September 13 that “the Umu-EzeChima Conference is willing to cooperate with all the families of Ugwu-NaObamkpa in resolving the present Obiship dispute”, and requesting a “joint meeting” with “a representative Committee of Ugwu-NaObamkpa” to “discuss the details of the points raised in your letter.”

Byron Maduegbuna stops by our house on his way up Ugwu-na-Obamkpa Road to Umu-Ase, replying to my inquiries about this accommodating response: the Conference will be happy to comply with the request to commit the Prime Minister title to Ugwu-NaObamkpa, since any such undertaking would (he said) be no more binding than had the various commitments Okosi II signed (before ascending the throne) proven during his subsequent reign, because the “King is above any law”10. He then leaves and hand-delivers this reply to the Secretary of Umu-Ase, obtaining his signature for its receipt.

Prior to attending the meeting of all Ugwu-NaObamkpa scheduled for September 14, Akunne Oranye (who as a senior elder of Ogbaba segment in Umu-Ase, has special interests in its current proceedings as father-in-law and supporter of candidate Onyejekwe) visits Byron briefly, where he sees his Family’s letter of September 12 together with the Conference’s response. Not having attended the Umu-Ase-Iyawo meeting previously convened by the Prime Minister, Akunne Oranye’s reading enables to him to anticipate their forthcoming discussion of the Conference response, and with this in mind he goes to consult on the matter with Nzekwu the Omodi, the most senior priest of the village and the man whose title designates him as its Hidden King. Together they plan their own tactics.

The Onowu convenes a meeting of all Ugwu-NaObamkpa , now including Ogboli-eke, Umu-Ase-Iyawu, and the non-royal parts of Odoje village11, led by all of their chiefs (including the Onowu and the Odu, who had engineered the meeting). The Prime Minister calls the gathering to order, then speaks about the attempt by the Royal Clan to usurp non-royal rights. Describing the Umu-Ase-Iyawo resolution and its dispatch to the Royal Clan Conference, in response to which (he says) there has been no reply, he ends his account by asking what the people of Ugwu-NaObamkpa should do. The Odu then speaks, arousing the crowd with accusations that the “so-called Umu-EzeChima” are greedy, want to become the dictators of Onitsha, and have now insulted the Onowu.

The question is raised whether the actions of the Royal Clan Conference Special Committee should be condemned. Then Nzekwu the Omodi arises, and says, we should not be hasty in condemning their activities. How long ago was the resolution sent? I hear, he says, that they have sent a reply to our resolution, and that this reply is not arrogant but rather conciliatory. We should await this reply. The Prime Minister responds, Well, I know of no letter. The Secretary is not here. And I know from my dealings with them that they are very arrogant and stubborn people.

Someone then suggests that a Committee representing all the non-royal clans should be organized to confer and decide what to do. Several prominent lawyers are present, and their names are raised for participation in such a Committee. The Asagwali (a lesser chief from Umu-Ase who is one of the Prime Minister’s close followers) rises and says, why bother with a Committee? Why not suggest that the Onowu select Enwezor as Obi right now? He will not oppose the traditional powers of the chiefs, and we will be finished with this Umu-EzeChima Committee.

At this argument, however, Araka the Ojudo (a Ranking Chief from a section of Odoje long harshly opposed to the Odu and his family) speaks in contradiction. We of Odoje, he says, have gone to our leader the Ozi (reputedly the oldest man not only in Odoje but in all of Onitsha, and a Throne Chief , generally regarded as a sage and for his honesty) and he has told us the truth: if Odoje is to support anyone, we support the Umu-EzeChima. But this is not the place to discuss the kingship anyway. We are here to discuss an “insult” against the Onowu.

Akunne Odiari (a senior, highly respected elder of a section of Odoje also opposed to the Odu and to Mbanefo family) rises to support the Ojudo. Members then begin discussing the formation of a Committee to discuss the Conference report, the subsequent Umu-Ase-Iyawu resolution, and the Conference reply. Finally the Prime Minister (who as the most senior presiding chief has the final word in a meeting of this type) says that each of the six non-royal chiefs might select three representatives from their respective segments to form a committee of 18, but that this is not the time to do it. And with that the meeting is closed.

Akunne Oranye, who remained silent during the meeting (because to have done otherwise would have aroused accusations about his interests in his son-in-law’s candidacy), is preparing to leave when the Odu summons him with a wave of his fan. Formerly the Odu has been a good friend of Oranye’s family, but has not visited him since the return of candidate Onyejekwe (the husband of Oranye’s daughter) from Lagos. When Oranye greets him with the salutation, “Odu“, the latter brushed his fan across the space between them and said softly, “Committee, Committee. We need no Committee. The Ndichie have already signed a secret Cabinet document which makes all these Committees unnecessary.”12

When the Royal Clan Conference Special Committee hears of the outcome of this meeting, they take immediate steps to expand their communication with the whole of Ugwu-NaObamkpa, sending a letter September 16 to the Secretary of Umu-Ase-Iyawu requesting a meeting with the “Representative Committee of Ugwu-NaObamkpa“, and distributing mimeographed copies of both this letter and that of September 13 “to all Ndichie and Di-Okpala of Ugwu-NaObamkpa.” They also turn to their allies in Oke-BuNabo, where (according to the memory of Peter Achukwu) the late Obi’s private files contain a secret pledge that had been made to Obi Okosi II and signed by Phillip Anatogu in 1958 when he was a candidate for the Onowu title, stating that he would not in future work against the Royal Clan in order to further the interests of Ugwu-NaObamkpa. This pledge, they thought, might prove interesting reading for the elders of Umu-Ase-Iyawu and indeed all Ugwu-NaObamkpa.13

Working with those chiefs from the non-royal clans who will cooperate with them (and going to the senior priests of those who do not), the Royal Clan Conference’s Special Committee manages to engage an ad-hoc counterpart Committee from among the non-royal clans to work on a formal Amendment to the Special Committee’s Report. This activity is much stimulated by a revelation which is now made public by the Umu-Ase-Iyawu concerning their Spiritual Heads.

Early in the Interregnum of 1961 I learn from Akunne Oranye about meetings being held in his village,14, but had not subsequently been told about their decisions. Now the leadership of Umu-Ase-Iyawu published and distributed a small, blue-bound pamphlet stating an Agreement that had been forged during those meetings in March and signed on March 29. This Agreement, entitled “Umu-Ase Families ‘Ofo‘ Symbol Agreement for the Obiship of Onitsha”, modified their traditional authority structure, stating that the five Senior Priests of this community — Nzekwu Omodi for Ogbo Family, Akunne Offiah for Okwulinye Family, Akunnia Bosah for Ogbaba Family, Akunnia Egbuna for Ukwa Family, and Akunnia Iweanya for Zoli Family — had agreed that “the right to confer the Ofo which is the symbol of divine right of the Obi of Onitsha belongs to Umu-Ase families above mentioned”, and that “the parties have agreed that the said Ofo shall be conferred on any Obi of Onitsha in the manner and under the conditions hereinafter stated”:

“1. That the Ofo symbol follows the Nze Shrine and that the Omodi of the Umu-Ase Quarters of Onitsha (hereinafter called the ‘Omodi’) who serves the Nze Shrine shall also confer the Ofo symbol on the Obi elect.

2. That on the death of the Obi of Onitsha and before another Obi has been elected the Ofo symbol shall be in the custody of the Omodi.

3. That the right of conferring the Ofo symbol on the Obi elect by the Omodi shall be exercised only in consultation with all the families hereinbefore mentioned and with their consent.

4. In the case of disagreement between the members of the families hereinbefore mentioned as to whom the Ofo shall be conferred if there are more than one contestant for the throne the families shall each elect by ballot one candidate in the family meeting and the representative of the family shall announce the name of the candidate so elected in a general meeting subsequently held by the members of the five families above mentioned and the Ofo shall be conferred by the majority of the five families aforementioned.

5. That the customary ceremony of Isi Nni Ofo (“Head money for Ofo”) by the Obi elect shall be partaken by members of the families hereinbefore mentioned.

6. That any conferment of the Ofo Symbol which is not made in accordance with this Agreement shall be null and void and any member of the above named families who takes part in such conferment shall be liable to penalty or ostracism.”

Names of signatories were then appended, including those of the five senior priests, the Prime Minister, the two other chiefs of Umu-Ase, and 31 other elders of the village. A photograph of the Onowu in his full ceremonial regalia graces the back page of the document.

The cultural modifications produced by this document are, first, to consolidate the position of Senior Priest of the entire clan (the priesthood associated with the Omodi title, that is, the Hidden King who traditionally administers the Nze — the Ozo title shrine of the clan) with that of the priest who controls the King’s Ofo during Interregnum. Second, my understanding of the provisions (as given by Akunne Oranye) was that this priesthood was now to rotate among the various segments of the clan (though this rotation is not specified in paragraph 1).15 Third, of course, the issue of which kingship candidate should be given the Ofo was to be resolved by balloting, the results of which were held to be binding upon all parties concerned (pointedly including the Prime Minister).

Thus the members of the Royal Clan Conference Special Committee find within the Umu-Ase-Iyawu16 a group of leaders who have produced democratising modifications comparable to those the Conference itself have evolved, and some of whose implications strongly favor the Conference faction provided they can reach concord with the elders of this non-royal clan concerning the issues raised in their Agreement. The Committeemen therefore readily compromise, abandoning both the earlier Royal Clan fantasy of recovering the ancient Anazonwu held Royal Ofo and of monopolizing future senior chieftaincy within their own exclusive ranks, and by mid October they submit to the Onowu an “Amendment to the Report of Special Committee of Umu-EzeChima on Obiship of Onitsha”, in which the Chairman of the Committee states he has been directed to say

“That paragraph 18 of the Report… dealing with Ofo has been entirely withdrawn and to say that the question of Ofo is between Obi elect and the family concerned in Ugwu-NaObamkpa.

“I am to say that in this connection the Umu-EzeChima of Onitsha Town stand by the (provision in the O’Connor Memorandum), which stated inter alia that Onowu should come from the families of Ugwu-NaObamkpa, consisting of Umu-Ase, Odoje, Ogboli-Eke, Iyawu, and Ogbe-Ozoma.”

These changes eliminate the central affronts to the interests of Ugwu-NaObamkpa people. The Prime Minister is however slow to respond, and when he does it is merely to return the letter asking for fuller coverage of signatures from members of the Conference. By the first of November he is still requesting further signatures, but at last the Special Committee points out to him the redundancy in these demands and concludes a November 6 letter with a final set of signatures and the request that “you will now cooperate with us in resolving the Obiship dispute.”

6. Problems now facing the Prime Minister and Enwezor

The months of September and October are clearly not good ones for the Onowu and the Enwezor forces. Aside from very disturbing developments within the Prime Minister’s own village, the complication of impending local and regional elections blocks Enwezor’s hope to “Go to Udo” during the time when the Royal Clan Conference is being stalled in its dealings with the chiefs. Despite numerous trips Enwezor makes to Enugu with his political secretary Aniweta and various members of the Peace Committee to request that Government decide in his favor, he finds that the Ministry of Chieftaincy Affairs has been sufficiently reminded of the critical paragraphs of the O’Connor Memorandum that it declines to intervene (at least for the time being). The Premier of Eastern Nigeria himself has pointed out to the Enwezor group that a hasty decision might hurt the NCNC in the forthcoming elections.

From the Onowu‘s perspective, he is experiencing a great intensification of political pressures not only from the Royal Clan Conference and from Enwezor but from other sources as well. On September 19, both the Spokesman and Observer report that the Prime Minister has sought police protection after an apparent attempt on his life during the midnight hours when (as the Observer put it) “four armed men… in disguise of thieves… fired a double barrel gun at him….” On September 23, the Observer headlines his statement that “he had not made up his mind to proclaim anybody the new Obi of Onitsha,” and that “no threat from supporters of any candidate for Obiship would force him to do what ‘is not right.'” An inference might be drawn at this time that the Onowu does not feel entirely safe even within the confines of his own village17.

Moreover, the Prime Minister now receives a letter dated September 27 from the President and Pro tem Secretary of Onitsha’s Ogbo-Na-Chi-Ani (“Age-Grade ruling the land”), directing his attention to an attached Resolution which the members of the Ruling Age set passed on the previous day, following their own secret ballot polled among their members between Enwezor and Onyejekwe (which Onyejekwe won by 14 votes to 2). The age set “unanimously resolved, that the candidature of Mr. J.O. Onyejekwe (Nnanyelugo) be supported in to-to.” The Resolution is copied to all of the chiefs and to the “Umu-EzeChima Committee”, and the covering letter concludes with the Ruling Age set’s request that the Prime Minister “summon a General Meeting of Onitsha Indigenes, with a view to place our views before you.” Coming from the Osita-Dinma, the Onowu‘s (and Odu‘s) very own age-grade, this additional sign of broad communal resistance could only be a troubling development18.

The Prime Minister also feels increasing pressure derived from higher-level sources in Government. From his own personal point of view much is to be gained from delaying a decision as long as possible because of his traditional prerogatives when acting as stand-in for the King, and he has petitioned the Eastern Nigerian Government to allow him to occupy the Obi‘s seat in the Eastern House of Chiefs as long as is required to complete the succession process. In his capacity as a member of the OUCC, he has influenced the Council to request that the Regional Minister of Local Government appoint him as Acting President of the Council until the new Obi of Onitsha becomes President upon his installation. But Government refuses both requests, Ministry officials insisting both that such an appointment might appear to “lend a support to the candidature of any aspirant to the Obiship of Onitsha,”19 and that a new Obi is necessary if Onitsha people are to be properly represented in several significant councils of Government. From the Onowu’s perspective, this means that he cannot not long delay a solution to a conflict in which his own standing-ground is being increasingly undermined.

7. Some pervasive contradictions are manifest

In the 1960s I often recognized normative contradictions when I encountered them, but grasping how to deal with them (analytically or in my own actions) was another matter. In practice, when for example I heard someone espouse the “rights of the people” in one context and saw that person act dictatorially in another, I tended to infer the speaker was “phony”, a hypocrite, which in turn implied my own assumption that there was only one “true” value standard and that either people lived up to it or they didn’t. This was in a sense my own dualistic “law of the excluded middle,” a true/false vision of reality. While today I do not entirely reject this view, I try to be much more careful in applying such dichotomies: social and cultural system “truths” are complex, often very hard to evaluate, and while we must grapple with contradictions when seeking to understand them, and more importantly to make decisions in relation to them, categorical dualisms often mislead.

In this chapter we encounter a flush of contradictions, revolving around the issue of Who makes decisions in and for Onitsha Inland Town. To the basic issue of “Who are the kingmakers?”, the old Colonial authorities of the 1930s contradicted one another (even themselves): “the chiefs are central to the process”; “they are peripheral”. While one faction in the 1961 conflict claims the absolute rights of the chiefs, their most authoritative leader the Prime Minister himself seems to back an expanding popular participation in some contexts (and chiefs suggest aspects of “democratic” equality for decision making among the chiefs themselves). The value prerogatives supporting the superiority of a “Royal Clan” is by implication contravened by externally conciliatory actions of Royal Clansmen themselves, but in other contexts they imply that royal prerogatives are absolute. Some of these contradictions seem to entail deception.

Today I would argue that the critical issue in these contexts is not primarily which side is “right” or “wrong” but rather how these persistent structural (and indeed, existential) contradictions are handled by parties involved. If people deal with contradictions by recognizing them as such, then trying to sort out the management of the conflict through exchange of perspectives, the outcome of such a process may include greater understanding of the contradiction, and if such understanding is implemented in subsequent action, may lead to a more complex system of relations (one capable of managing more complicated patterns of information). Dealing with contradictions by concealment and deception, however, tends to interfere with such a process. Gaining a point by deception regarding some standard of value may “win the game” in the short run, but in the long run that method tends to undermine the very value being proposed.

Of course, from a postmodernist perspective, “deception” like “truth” is a relative term. In one sense, nobody can say anything without it, since the very categories to which speakers must resort twist the fullness of reality. More broadly, we have to choose how much we want to reveal about our perspectives on any subject: sometimes truths spoken can have incalculable, injurious effects.

But to adopt a consistent postmodernism, even our relativisms should be relative: some kinds of deception undermine ordered social systems by engendering entropy, tendency toward chaos in them. This is especially true where they erode trust among participants. If therefore we wish to foster greater complexity in a given system, we should be very careful about the use of deceptive means. Prospects of choice are involved.

While I had early come to expect considerable secrecy (and probably dissimulation) from Enwezor’s side, Byron’s comment about the low cost to the Conference of their short-term conciliation with the non-royal clans was troubling to me. Now why I felt this way seems clear and it is an example of a generic form we have encountered elsewhere in this text: consistency of promises and subsequent actions becomes a problem when the longer term impact of the agent’s activities upon others (and the relationships involved) is deemed sufficiently significant to engender concern about trust.

8. Higher-level Politics Intrudes on our “Searchings”

While following the intensifying efforts of the parties directly involved in constructing our current Interregnum, we must remember that in the wider contexts of The New Nigeria (and beyond), larger-scale intensities of conflict are brewing throughout 1961, but they peak for Onitsha and Eastern Nigeria during October and November. The time frame we’re looking at right now marks the end of the first year of Nigerian Independence, and our two local newspapers are bulging with the facts, fantasies and assessments of that turbulent scene. The Eastern Observer calls for “democratic-socialist” revisions of the national Constitution (to break away from colonial- and captialist-domination of the Nigerian economy), and for greater equity among the diverse regions in Nigeria, while the Nigerian Spokesman rejects nationalizing industries, celebrates capitalism, and relishes the undisguised efforts of the now-ruling coalition power at the Federal level (the NPC Muslim rulers of the North and the NCNC Igbo-dominated rulers of the East) aimed directly at fragmenting the AG-ruled Western Region (and thus weakening the base of that Opposition) while keeping their own regions intact.

(Retrospectively,) evidence from events on this national scene appears to promise an ominously explosive future for Nigeria (and in fact diverse reportorial sources during these months employ that very metaphor to describe the likely prospects for Nigerian unity), while in Onitsha, some of the local Interregnum activists find they must leave the domain of Onitsha Kingship and instead scramble to perform their perceived tasks in the local varieties of the national electoral game

- This ikenga was over two feet high, one of the largest I ever saw in Onitsha. [↩]

- See Harding 1963:113‑14. [↩]

- The eminence of these two men, involving not only their roles in that family’s extended land litigation with Obosi but also their substantial and current national prominence, is at least equivalent to the local statuses of the Omodi and the Onowu. [↩]

- This is a change from the Special Committee Report, which calls for nine cows, one to each of Onicha-Ebo-Itenani (“Onitsha the nine clans”). Committee members found that agreement could not be reached on which social units comprise the nine (while the six major villages can be consensually defined). Some apparent confusion between “six” and “nine” persists throughout my research, and among the “nine” no two persons seemed to give exactly the same list. See Henderson 1972: 77,126,410,504. [↩]

- The practice of “redeeming” one’s gear is integral to the Onitsha procedure of title taking. See for example Orakwue 1953: [↩]

- This latter group is of course the major village containing the “descendants of Oreze.” Note that Isiokwe and Umu-Olosi are not included in the list, while Oke-BuNabo is rendered as “Umu-Dei“, a common and persistent conflating of categories in Onitsha [↩]

- Then Acting‑Resident O’Connor himself said in paragraph 5 that, in facing mutually contradictory constructions of “native custom”, “the best that could be done was to accept what appeared to be the most rational tale.” “Most rational” for Resident O’Connor clearly meant in this context the version of tradition most congruent with the Government’s current view of a proper succession process. [↩]

- See Henderson 1972: 442,454-62,467-69 for my own discussion of these problems. [↩]

- See Henderson 1972:268 9,458 59 for the basis of this right as formulated in oral tradition. [↩]

- The implications of this perspective for long-term trust across the wider community are obvious. [↩]

- Ekenubene, Ogbe-Ndugbe, and Odimegwugbuagu. [↩]

- My account of the meeting derives from Oranye, who provided the “quotations”. Regrettably, I did not consult with the Odu about the event. Oranye was another Onye-Onicha highly-respected for his honesty. [↩]

- This oath requirement was a response to the boycotting of the palace by the Ugwu-NaObamkpa leadership during the previous 15 years because of the King’s persistence in conferring the Onowu title on a man of the Royal Clan, the aim being to preclude future boycotts for other reasons. The existence of such an oath in writing would prove very embarrassing to the Prime Minister (as “political leader” of Ugwu-NaObamkpa) in the present context. [↩]

- See Chapter Four, “Parties Proliferate.” (Note that in March the sponsoring group was named as “Umu-Ase“, not the more inclusive named category we have seen emerging now.) [↩]

- More exactly, I understood that rotation would occur among the four units of Umu-Ase, Iyawu being only recently amalgamated into the group and not regarded as eligible for the priesthood. [↩]

- Use of this combination term now became more standard. Note that the March 29, 1961 document, though including Iyawu in the text of the agreement, was entitled “Umu-Asele Families”. It seems likely that the Iyawu elders demanded such nominal inclusion as a condition of their cooperating within this new social movement. [↩]

- Note the Observer‘s assumption that the gunshots were not fired by “real” thieves. [↩]

- Somewhat later, the Ekwueme age grade — the previous and more elderly, now retired Onitsha “Ruling” age grade — backs this stance of the Osita dinma. [↩]

- Nigerian Spokesman Oct. 3, 1961. [↩]