[Note: Click on any image you may want to enlarge.]

To begin with historical overview: Obiekwe Aniweta was born and raised in Onitsha, the senior son of an untitled, poor farmer and his Onitsha wife (both of whom had lived most of their lives in Onitsha). His father died while Obiekwe was a child, leaving him in a severe financial situation, but the Mother’s People (Nne-ochie) of his father, the Ekwerekwu family, were wealthy Onitsha landlords and played some part in fostering his education. He attended primary school under the CMS and then secondary schools under the Roman Catholic Fathers, where his own willfulness began to come into conflict with theirs. He married an Onitsha woman and lived with her, their two small children, his mother, his junior brother and the latter’s wife, in his father’s modest house in the Inland Town. Most of his life experience had centered around the Inland Town, though he had recently worked briefly as a secondary school teacher at the National College in Oguta and was now employed as the Principal of the Premier College, a struggling private commercial secondary school located in the ramshackle “town hall” of the Onitsha Improvement Union. The job gave him considerable free time, since he only occasionally visited the premises of the College to inspect how things were going there.

Helen and I were very lucky to meet him by way of Ikenna Nzimiro, whose importance to us regarding smoothing our entryway into the wider community was probably greater than we realized at the time (October 1960, just after Nigerian Independence Day) since we were with Nzimiro only very briefly (he was on leave from working toward his Ph.D. at the University of Cologne). He came to visit us at 24 Mba Road, and our rapport was immediate and (for Helen and me anyway) fairly intense. We traveled with him to his home town of Oguta shortly afterward. Together we formed the bond as dedicated social scientists, Ikenna rather more Marxian in orientation, I more strongly attached to the perspectives of Talcott Parsons. We found a great deal to talk about in the brief days we were together.

Obiekwe and Nzimiro had known each other in Oguta when Aniweta had worked there. I took no pictures of our meeting at the time, and afterwards Helen and I made so many other social contacts that I largely forgot about the meeting. (Nzimiro took us soon thereafter to meet Mbanefo Odu II in Odoje, an event sufficiently memorable to erase those of less prominent men1 . Below you can see Aniweta’s exasperation at this foreign photographer who is blithly filming the crowd while totally failing to recognize him.

This new meeting occurred the following April, and I now explain the failure to recognize him in the following way: meantime Helen and I had experienced a cosmic wave of African faces that had simply overwhelmed our memory banks. Our first intense experience of this was at Independence Day celebrations on October 1 1960, which took place at the Onitsha Sports Stadium (See Chapter 3, “Nigerian Independence Day”). Never before had I seen such a diverse array of faces, of many colors but predominantly very black, and their countenances bore even greater variety, with little resemblance for the most part to the stereotypes accepted as “typically negro” in the lands where we had grown up. As one minor example, see this image below:

My camera use was slow to recognize the problems set by combinations of very intense sunlight and mainly very black faces, a problem I never fully mastered. But one very potent learning experience was etched into my brain in moments like these: stereotypes of Africans (based on physical appearance or otherwise) are of very little value in grasping what kind of being each one of them is likely to be.

In any case, once I made my memory-failure amends and we began visiting together, we quickly became co-workers, and began to make a kind of census survey of his larger sub-unit of Umu-Aroli, that is Umu-Anyo a portion of which we can see from the viewpint of Obiekwe’s own sub-sub-village of Umu-Aguzani. At left, Aniweta stands among some of its thatch-roofed huts in the image, wearing his typical daytime garb of white dress shirt and dark slacks. Beyond him, across an open space, stands the pink shrine dedicated to Ezumezu (a Spirit of childbirth), and to its left is the concrete-block storeyed building under construction by Michael Enwezor, a junior brother of the new Igwe whose Ima-Nzu ritual we had observed in April.

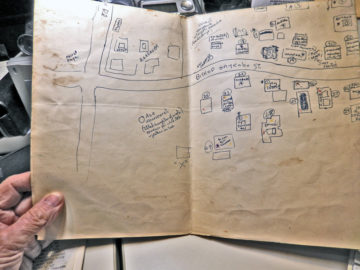

At left, a quarter section of the map compiled during our Umu-Anyo census. (Ifekandu Umunna, also a member of Umu-Anyo, participated in this work, so the three of us sometimes operated as a team in this context.)

At left, Helen and I participated in a personal ritual being performed by Obiekwe’s mother (she sits here center-image) in the Aniweta iba kitchen . The ritual objects are in the foreground. Obiekwe’s wife stands beside him holding the younger of their two children. 2

At right, Obiekwe’s wife brings water from the public faucet along Bishop Onyeabo Street. This particular portion of Umu-anyo was one of the most “un-developed” areas we enjoyed while living in Enu-Onicha. it had a feel that must have been something like Sylvia Leith-Ross described for the entire “Inland Town” in 1937.3

Although he was an active family man, Obiekwe made it clear to me that he pursued active sexual congress whenever he pleased, and as a confident and handsome person he no doubt pleased others as well. One day observing to me that on the previous night he had engaged in “serious poking”, he suggested to me that I might enjoy some of the local women as well. As an anthropologist, I went with him to the Easy Life Hotel and Bar on Old Market Road, where we had a beer at a table in the cavernous interior while a number of (to my taste, very corpulent) women sat around regarding us (the sole customers at the time — it was early in the day) without any apparent interest. As we sat there, Obiekwe observed to nobody in particular, “Mr. Henderson is not serious.” And indeed I wasn’t. 4

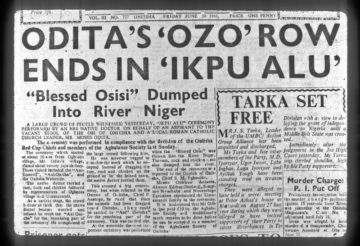

By this time, Obiekwe was heavily involved in the 1961 Onitsha Interregnum (see Chapters Five and Six in this volume, “Sought But Not Seen”). Below marks one indicator of his local prowess: the demolition of the Obiship candidacy of one of Ndi-Onicha‘s most famous sons, Moses Odita at the end of June, 1961, reported in the Nigerian Spokesman of June 30.

This accomplishment was entirely due to Aniweta’s behind-scenes investigating and maneuvering in opposition to candidate-supporting schemes then being covertly directed by the local Roman Catholic Mission Fathers.

This event in particular illustrates one negative consequence of my open association with Obiekwe during the Obiship contest: while some members of the community may have viewed this connection as positive, for others my presence became much more negative. For example, late in our Onitsha stay, my assistant Ifekandu Umunna escorted me to consult with a very prominent member of Umu-EzeAroli, the elder Akunnia Mbanefo, often referred to as “Ofo Diali” since he served as Diokpala of a son of Obi Akazua. He is shown here at left, wearing two feathers. While he admitted us into his Iba, he gazed with fixed jaw and staring eyes at me, adamantly refusing to engage in any discussion. Only later did I recognize his direct affiliation with candidate Moses Odita. 5

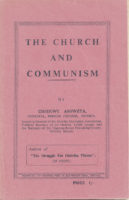

Before we departed from Nigeria, Obiekwe published his Onitsha pamphlet entitled The Church and Communism (1962), a substantial tract of twenty chapters (most of them quite brief) and a concluding section entitled “Conversion to Communism By Peaceful Means”. A brief summary of his argument may be stated as follows: The Roman Catholic Church steers Nigerians through its implement, the Eastern Nigerian Catholic Council, which defends neo‑colonial exploitation by raising the specter of Communism and attacking the USSR, distorting its character. The Church’s behavior belies its words: it preaches reconciliation and practices hatred and lying. If communism is a “religion”, does it not deserve freedom of belief? It has similarities with primitive Christianity ‑‑ persecuted minorities, fanatical, destiny‑committed, internationally‑oriented, appealing to the poor and oppressed. (Obiekwe told me around the time we were leaving Onitsha that “I am now going the Chinese Way”, but eventually he did attend Friendship University in Moscow at least for a time.)

Obiekwe continued his very active support of Igwe Enwezor throughout the 1961-62 contest, and readers of this page may of course follow the finer details of his efforts during the Interregnum in Chapters Five and Six, “When the Obi is “Sought but Not Seen”.

The Interregnum culminated in the Harding Commission’s Inquiry of 1962. During the inquiry, while Candidate Enwezor and his prime supporter Egbunike the Onya were presenting their testimony, a number of their prospective supporting witnesses (including Obiekwe Aniweta and barrister Luke Emejulu, as well as two senior elders) were excluded from the witness list after sharp‑eyed opposing counsel observed them violating the Commissioner’s ruling that prospective witnesses must not attend the hearings. The eventual published report dictated that Enwezor lost. 6

We continued to follow events as best we could through the Nigerian Spokesman, which arrived in our mail in bundles continuously (if somewhat sporadically) from the summer of 1962 until the Nigerian national disasters of 1966.

From the time of our departure onward for some years, I learn of Obiekwe mainly through his occasional appearances in the Spokesman:

On August 26, 1963, he writes a long essay regarding “the crisis in Umu-EzeAroli”, in which he condemns the Umu-Chimedie branch of the descent group (the segment that includes the new Obi Onyejekwe), arguing for the separate rights of “Aguzani Family” (a branch of Umu-Anyo, Enwezor’s central location, but oddly he does not mention UmuAnyo in the argument). He argues that the four other branches of Umu-EzeAroli should make “a complete breach” with Umu-Chimedie. (O’Conor Ejo, “University of Lagos”, responds to this essay on August 30, commenting that those defeated in this Obiship contest are now being pushed forward by other men until they are “drained to their last pennies”, and states that “the battle is over”, it is wrong to give false supports.)

Obiekwe briefly re-appears November 13, but now “on behalf of youths of Onitsha” to praise the prominent Onye-Onicha Chuba Ikpeazu (now Queen’s Counsel in Lagos), who has recently donated £50 to the new Obi’s palace construction fund.

On February 13, 1964, under a small headline stating “Obiekwe condoles Enwezor”, it is noted that following the recent Federal Supreme Court of Nigeria’s ruling in favor of new Obi Onyejekwe, Obiekwe, “one time Political Secretary of Ogbuefi Nnanyelugo Joseph Enwezor, now in one of the University in Nigeria” , “has sent a message of condolence to Mr. Enwezor: ‘Allelujah Supreme Court Ruling Obiship vindicates me x Your flatterers become weeping Jeremiahs x May your political soul rest in peace”. This is followed by a second article, under a bigger headline, an essay by Obiekwe on “Why Enwezor failed”, which takes up this question in much of this and, subsequently, of the February 14 and 17 issues of the Spokesman. The details of this extensive analysis belong elsewhere, but suffice it to say overall it is thorough, cogent, and illuminating. Color him brilliant. 7

The fine details of Obiekwe’s brilliant analysis of “Why Enwezor Failed” as published in the Nigerian Spokesman newspapers we received in 1964 are recorded here in the entries for February 13-17, 1964, in Chapter Eight, Some Aftermaths: Nigeriaan spokesman 1964-65. Here he gives a list of 15 reasons why Enwezor failed. I have to say — as the author of the Chapters in this volume covering the Obiship contest — that he brings in more “rreasons” than I was able to identify. Of course, he should be able to do so — he was much closer to the action than any outsider could be. That said, he showed real brilliance in this latter essay.

For more details on the career of this remarkable man, see in Chapter Eight, “Some Aftermaths”, the page on “Onitsha 1992: Brief Encounters…” There I was able to re-connect with him in Onitsha, long after the end of the Biafra Civil lWar, during which he lost the use of one eye. There, the first words he said to me were, “Mr. Henderson, I have become a capitalist!”

- See “Scatterings of Truth” in this chapter. [↩]

- in 1992 he told me he now had 25, by four different wives, while his first one remained with him but not residing in his new headquarters. [↩]

- See Chapter Three, “the New Nigeria…”, page on Enu-Onicha for one of her comments. [↩]

- This kind of behavior was simply out of the question for me, for any of a variety of reasons, body fat indices being entirely irrelevant to any motivation I might have carried. [↩]

- See Chapter Four, “Parties Proliferate”, section 5 on “Ofo Diali”. [↩]

- See Chapter Six, “Harding Commission Inquiry & Report, et al”. [↩]

- Interestingly, he now salutes his former object of great contempt, J.O. Mbamali the Ajie of Onitsha, as “an intelligent, educated, proud young gentleman”, for whom “I have the greatest respect”…. This stance is quite different from his assessment of the Ajie published in the Eastern Observer of May 9, 1961, where he remarked that “The Ajie should be given latitude for his intelligence”, that he is “subject to hallucinations” and bears proverbial similarity in his behaviors to those of “a greedy dog”. [↩]