Above: Robert McWhirter in Onitsha, 1909, on bicycle; Annotation says ‘ notice shotgun on clips”.

[Note: Click on any image you may want to enlarge.]

Note: it is with heartfelt thanks to Helen Gee and her husband David (retired educators who reside today in Armidale, Australia), that we have obtained these outstanding photographic records of Onitsha during the earliest years of the British Colonial Government establishment here. The photographer, Robert Carnie McWhirter, (Helen Gee’s grandfather, a native Scotsman) came to Onitsha in 1905.

Mr. McWhirter was instrumental in building (and/or maintaining) new Government establishments, bridges, and other features of Western technology that substantially transformed the spaces that became known as “The European Quarters” of Onitsha during his six years here. Regarding his photography Mr. McWhirter said in 1963 (when he was 83 years old):

In my younger days I was very keen on photography, in these days we used glass plate negatives, not films, and we did all our own developing and printing. In fact, the most interesting thing was watching the image coming out on the plate in the dark room. While in Africa I did a lot of photos, and it was usually under difficult conditions. Rigging up a dark room was a problem, then there was no running water to wash them. I had to rinse the plates and prints in a bucket of rain or creek water. This water was often so warm it melted the film on the plate, and I lost dozens that way. Still, as you would have noticed in the prints I sent you a while ago, I managed to get some good sharp negatives, and the camera I had then was a clumsy box camera which cost me about 30 shillings.

So different are some of the images of Onitsha that we see here from what the Henderson authors of these pages encountered in 1960-62 that understanding exactly where some of the images were taken poses a number of problems. Unfortunately, as anthropologists we neglected to document (or even visit) many of the places Mr McWhirter photographed (we never entered the Public Works Department (PWD) establishment, for example, nor the Leper Settlement, nor most of the European Quarters for that matter). We were “anthropologists of the 1960s”, when “Western” things were of less interest in our eyes, and our hearts (and heads) were largely devoted to the Inland Town (Enu-Onicha).

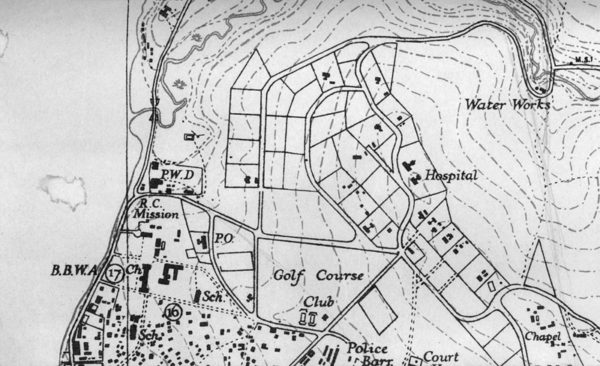

The map at left here, from 1957, shows several of the places where Mr. McWhirter worked from 1905-1911: the Haulk Suspension Bridge, the Public Works Department (P.W.D.), and that part of the European Quarters where the Catering Rest Housing (for European visitors only in 1910) was located in those days.

the suspension bridge across the mouth of Nkissi Stream was a major technological accomplishment for Mr. McWhirter’s time, but a necessary one since Nkissi Stream is deeply incised, and embankments along the river here are high. See, for example, our 1960 photo at right which shows some of the “Marine Qtrs” as well as the dropping landform associated with the stream. This was, taken from the passenger ferry when we first arrived at Onitsha.

At this location the combined flow of the two large rivers (the mighty Niger, plus the important Anambra River)1 cuts strongly alone the entire reach of these hills, creating steep banks, and the equally bright reddish cliffs of the also-incised Nkissi Stream may be seen behind the rectangular street sign visible at far right in the image.

The fact that a technical accomplishment of the magnitude of this bridge was a primary operation undertaken by the new Colonial Government reflected the importance of developing this part of the city immediately, in order to situate what were then deemed certain critical functions there, including nearest to the rest of the city, the new Prison. (Unfortunately, no photographs of this prison survive in his collections, but see further below for a photo McWhirter captured of a presumably comparable structure in Asaba on the west bank of the Niger.) More of these northerly features will be shown further below.

Below, his photograph of the Suspension Bridge, presumably taken from the small spit of land just east of it. It must have appeared, for Onitsha residents, , somewhat like the Eiffel Tower (built at about the same time) looked for the people of Paris.

McWhirter did record a photo of the Public Works Department complex he was responsible for building and/or managing (below left), and his surprisingly large and luxurious-appearing “European Guest House” (below right). Further below, see his “Nurses Bungalow” of 1908, of comparable quality. We presume these buildings were located where similar-functioning buildings existed in 1960-62, but we’re uncertain whether any of the particular physical features survived till that time (we anthropologists tended in those days to slight much of “Western” culture and our own 1960 Aires camera hardly ventured there at all).

Both of these two residential complexes are raised well off the ground on pillars (with substantial work spaces enabled therein, while the residence areas upstairs are full of windows (probably protected by wooden operable shutters, since fine-mesh metal screens were not in use in those parts of Onitsha where Helen and I frequented as late as 1960-62). In any case, it would appear that quite a few (presumably entirely European) nurses were in residence by 1908. “Bungalow” sounds to my ears an odd word for this very substantial nurses’ building, but the term derives from British “Raj” usage for colonial officialdom residences in India, defined as a “Bengali style” house (from the Hindi word Bangala), having prestigious overtones in these contexts.

At this point we need an earlier map, but I lack anything prior to 1932 that provides the kind of detail which might tell us where these two buildings directly above were located. Here is a portion of the official colonial government version from 1932:

While we have no photos of the Onitsha prison, I I attach here the photo Mr. McWhirter took of the Asaba prison that pre-existed it (across the River).

Regarding the 1932 map above, we initially note several relevant features. The Public Works Department buildings shown are located exactly where they were in 1960-62 (just north of the Roman Catholic Mission Property. on the Street labelled “PWD Road” in 1960-62), while the feature labelled “Hospital” at right-center here in 1932 has disappeared by 1962 (presumably replaced by Onitsha General Hospital, a much larger complex located well off to the east of the map shown here). We may perhaps assume that the “Nurses Bungalow” built in 1908 was located somewhere near the Hospital shown in 1932. Second, note the site of a “Court” directly south of the hospital at the bottom of the map shown here. The street on which the Court is located has become in 1960-62 “Court Road” and the Magistrate’s Court is now located at the place so marked here in 1932. (The Police Barracks etc also remain in 1960-62 where they are shown above, though considerably expanded.) The “Judge’s Bungalow” of 1911 might have been located here; its image shows a paved circular drive suggesting official traffic, and its downstairs verandah might have accommodated discussions including court hearings (with an upstairs retreat for “those who judge”), but it may also have been located further north in the early European residential area near the hospital (also near the 1932 golf course and “Club”). The locations marked “Club” on the 1932 map had become integrated by 1960-62, and the golf course had been abandoned.

Now note two other prominent features of this 1932 map.

First, along the coast, prominently demarcated as “B.B.W.A.”, is a place indicating the British Bank of West Africa (located along the Marina Road and suggestively close to the Roman Catholic Cathedral, perhaps as a measure of spiritual protection in 1932). This may or may not reflect the location of the bank photographed by Mr. McWhirter, which is differently labeled as shown here below:

Note the spikey iron fence (distinctively sharp-pointed rods at close intervals) fronting the building (the apparent storm cloud hovering above the complex may be an artifact of the film-processing, though it looks like a whirlwind), and note also that the building appears to be topped with an array of lightning-rods (the dark horizontal line above the left part of the roof may be an artifact of damage to the photo, or perhaps a significant feature).

Here is a closer and sharpened view of the building:

Here you can clearly see an authority figure overlooking the perimeter, and what would appear to be several extruded “look-out” positions at that same level. The lower portion appears to be made of large bricks of some kind, the windows again look louvered but with what kinds of shutters is unclear (I would guess iron or steel). It does have a sort of “fortress” look about it to this unlettered observer, at least the upper storey could be readily used as a defensive (and presumably armed) retreat.

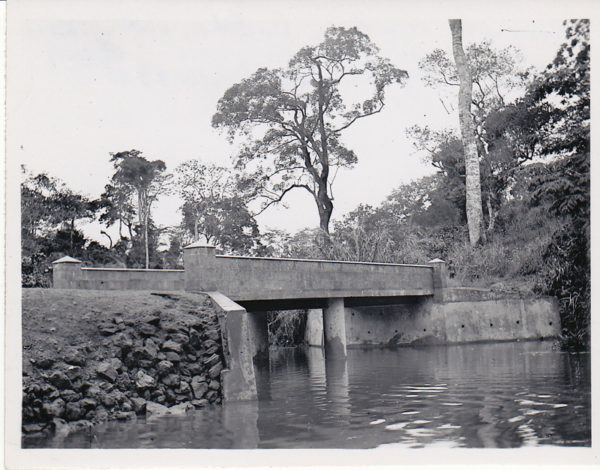

Second, at far upper right on the 1932 map above, see the “Water Works” located on the flank of the northeastern base of the grand hilltop that encompasses much of this European Quarter, and which is reached by by a road (which in 1960-62 has become “Nkisi Road”) that runs from that point outward from Onitsha to Nkwele, Nsugbe and beyond). Here it is shown to be bridged, and (see below) the Water Works of 1932 clearly drew on a substantial stream, and in those days,it must have been relatively pristine — indeed it was regarded by ancient Ndi-Onicha as profoundly sacred, and to the jaded eyes of today-Arizona-desert-dwellers, it looks like a really substantial and beautiful river. (When we saw it during our brief visit in 1992, it was but a trickle and obviously seriously polluted; a very unhappy ending due to the perennial curses of urbanism, pollution and overdrafting.)

This is a very solid bridge, obviously designed to carry motorized traffic to the Akpaka Forest Reserve nearby as well as to the towns further northeastward in Onitsha Division.

To consider further images, it becomes convenient for us to insert another, simplified version of the 1932 Map.

Here, note specifically the Leper Settlement, located at the far northern edge of the complex, just beyond the Obele-mmili Stream (lit., “small water”), which is also a substantial waterflow, deeply incised and draining a substantial watershed that (like Nkissi) includes part of Nkwele town. Reliable access to it obviously required a bridge of good quality to cross it (and Mr. McWhirter built one, see further below).

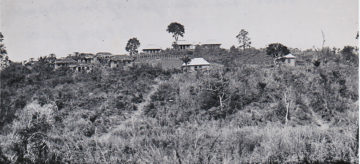

See his photograph of the Leper Settlement at right. Enlarging the image shows clearly a horizontal dirt pathway, then two hill-rising dirt pathways, leading to, at upper left, an array of thatched dwellings, and toward the right and on the hilltop, five pan-roofed buildings. I can say nothing further substantial about this settlement at this time.

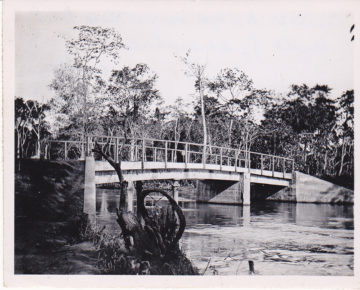

Below, this is apparently a footbridge built by Mr. McWhirter to span the Obele-Mili Stream in order to have settlement access (and also, as the roadway on the map shows, to the adjacent riverbank).

I make this inference despite Mr. McWhirter’s own caption, attached here, which states “Nkissi” as the stream, because we can see from the 1932 map of this area that there are precisely three bridges crossing substantial streams on the north side of Onitsha, and one of them shows a crossing over the Obele Mili just below the Leper Settlement. The Government would have wanted a bridge there, but not necessarily one that could carry motor vehicles. Like those other two bridges, this one is obviously very well made by our authority for this page.

The image at left speaks for itself. The resolution is insufficient to discuss details about the people shown here. This building was located along the route which soon became known as the Onitsha-Enugu Road.

Here, Mr. McWhirter sits in front of the European Guest House he has constructed.

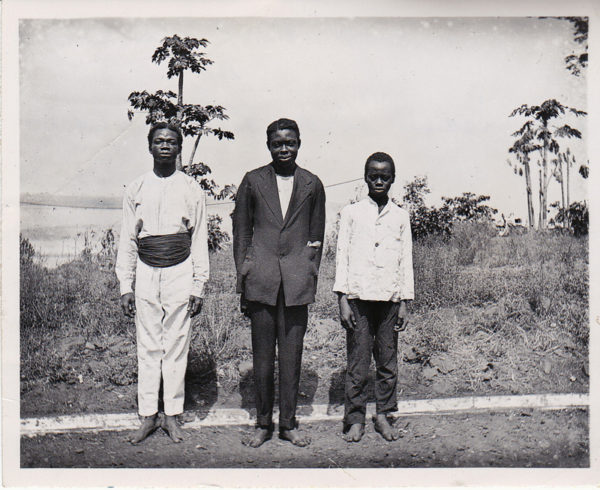

Now we turn to Mr. McWhirter’s photographs that focus more on local people.

In this image, all three men are apparently bare-footed. The man on the left is McWhirter’s cook, dressed in white (?) long-sleeved shirt and trousers. He appears to be wearing what I learned in 1961 was called a “cummerbund”, which I personally saw at only one occasion: a party in Onitsha involving mainly expatriates associated with the then brand-new University of Nsukka, where it was worn by an Englishman. He showed some amusement at my ignorant questioning what it was (it was colored fairly bright red as I recall).2

The two men to the cook’s left wear what I would call “sport suits”, without tie. I assume that one or both of these two were called “small boys” by the cook.

In September1960 menservants at the Catering Rest House wore costumes similar to that of the young man standing at far right, though they were of one color (beige or tan as I recall). We hired a man to become our cook and housekeeper who wore clothing somewhat comparable to this attire.

As an aside, I note that his name was Thomas, and he bore a formal letterbook (as I learned when I soon thereafter fired him for gross misbehavior and he asked me to make another entry in it) that contained a single recommendation, from an Italian man from some considerably previous time, who commented mainly (and briefly) that Thomas was “very honest”. Thomas immediately began cooking food for us that was very nearly inedible even by our modest standards, though it was competently performed in what I can only assume was some version of “Old Colonial Style” (heavily laced with a condiment called “Marmite”, otherwise it was beyond bland to our tastes). He soon demanded that we hire a “small boy” to help him, which we did, and soon thereafter he would disappear for extended periods without informing us, and made a series of petty demands that I now forget but which then seemed preposterous. Desperate, I called in Byron Maduegbuna (see “On Byron Maduegbuna” for details about our masterful guide), who mediated as I acted out several weeks of accumulated anger, ranting out the details of Thomas’s recent behavior. Thomas’s sole response was a very brief assertion about contemptible “colonialist masters” (and so he found himself fired just a few weeks into Nigerian Independence, by Americans who regarded themselves definitely non-Colonialist in their personal values).

We kept the “Small Boy” he had brought into the house, Michael Okolo (see a photo at left of him ironing at our kitchen table while Helen types her notes). A young native of Nsukka, aged 22 and on when we knew him, he was unfailingly loyal and hard-working, helped to teach Helen how to cook proper Igbo food (which to our tastes she mastered completely), and did everything that needed to be done around the household. He always wore a short-sleeved shirt and shorts of his own choosing, and was always impeccably clean. (He once voluntarily washed the engine of our Fiat 600 with water and rags, the only exasperating misstep he ever made in our experience.)

I will comment further below on my substantial ignorance regarding the history of Onitsha dress styes, but perhaps readers have here gained some sense of our preference for casual lives.

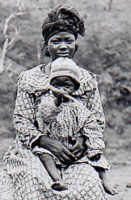

Above, we now see McWhirter’s cook together with his family. His attire perhaps requires no comment from me (other than an apparent source of the meaning of “stiff-necked” in American culture), but perhaps a closer look at his wife and child will be rewarding. Setting aside her interesting hat, I suspect the child is a boy (very thoroughly and warmly dressed), who appears to be flipping back and forth some kind of long and flat slender stick.3

This image at left was presumably taken in Enu-Onicha, though no particular location is indicated. The building looks similar to a number of small houses still apparent in the Inland Town in 1960-62, but for me the icons marked in dark paint on the front wall are of distinct interest. After looking at them closely and wondering, I searched our own photographic archives to see if more recent buildings held comparable features.

Here compare a view above right of an ancestral house that I visited in 1961. Similar though not identical icons are present, rendered in white paint. (Unfortunately while in the field I took no notice of these rather small features, and so didn’t pursue them. Presumably they reflect significant statements of some kind, made by the resident-owners.)

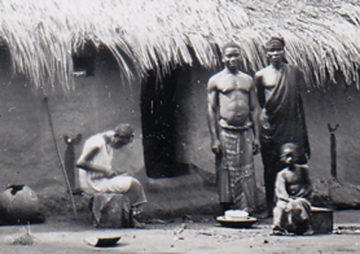

Below, a closer view of the people present in this scene. Here (and further below), I will largely disregard the dress of the women. My observations of the dress of both men and women in 1960-62 were primarily aesthetic in content: I did definitely notice dress but largely in a non-verbal, mainly sensual manner (this is sad to say but even more sadly, true). I hope to obtain some real expertise on these subjects from ethnographic experts and will insert it with their citations here when I do, but meanwhile will simply register what my own vague memory banks suggest to me.

The man standing by the doorway left is wearing a “wrapper” (also called “lappah”), in the manner rolled at the waist, his body nude above. This looks like a casual family scene perhaps, but I think it’s likely something of ritual imporance is happening.

In 1960-61, I do not recall ever seeing such dress outdoors except when it was worn in formal, ritual occasions — see for example here below the garb worn by Ononenyi Gbasiuzo Okosi at Obi Okosi II’s funeral in March 1961:

This man’s dress may indicate he is playing a role as Di-okpala. At his feet stands a bowl containing something that may have ritual importance, and the young boy seated nearby is holding what looks like a small “fan” which could be a ritual object of some kind, again something I don’t recall seeing in 1960-62 in the hands of a boy and with that pallid, fur-like form and shading.

The man standing to the right of the prospective Diokpala in the household image at left above, on the other hand, is clearly formally dressed for this early twentieth-century occasion, but in a different way, with a hat and shoulder draperies. (See him at left, here.) I have no memory from 1960-62 of observing any Onitsha man dressed in this one-shoulder-bare formal style. Indeed, I don’t recall seeing any non-Onicha Igbo man wearing a formal attire of this kind.

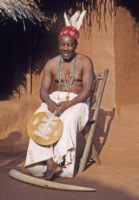

Now regard below the most formal scene to be found among any of McWhirter’s available photographs. I am also reasonably certain that this is an Ndi-Onicha group, mainly on the grounds that the two main men shown look facially very like Onitsha men familiar to me (especially the man at right wearing the pointed hat and holding the thin staff).

This image may well provide a virtual textbook of Ndi-Onicha formal dress styles from a very early twentieth-century time. Unfortunately I am ill-equipped to provide genuinely informed readings/translations, for which I hope to “recruit helpers” to do so. Meanwhile I will do whatever I can in further discussions below.

The man at far right here, holding the hand of a person who is presumably his daughter, looks like an Onitsha indigene to me. (I leave the women for other commentators both physiognomically and sartorially, but it must be remembered that at this time male Ndi-Onicha engaged in an unusually high rate of marriages with women outside of the Onitsha community (wealth disparities between Onitsha and its neighbors were very substantial, so an Oke-Onicha could often provide bridewealth less readily available to what they labelled “bush people” ), so the appearances of married women seem to me rather more highly variable than those of the men).

This man (wearing an outfit whose elegance is likewise highly typical for Onitsha men on formal occasions in 1960-62) again displays a visual feature I never saw among them: the one-shouldered-bare pattern we saw in the image further above.

At left: From a 1960s perspective, the woman at far right would definitely appear to be non-Onitsha in origin. She, and especially her child, appear to have their hair shaved well back on the forehead, not an Onitsha style recently, and we never saw anything like her spectacular brass disks anywhere in the Nigeria we encountered in 1960-62.

The young boy in front wears the lappa, nude from the waist up, a formal style in tune with the others in the photo.

At left, The man in the middle looks facially to me like an Onye-Onicha. Again, his dress style shows typical elegance for a “Real Onitsha Man”, but in 1960-62 they do not appear in this partly-bared- shoulder style, nor with this kind of peaked hat. We saw the Bowler Hat (apparent on the man at far right) only once in 1961-2, on the head of a non-Onitsha man, at Obi Okosi II’s funeral (below).4

Again, note at the left, the young boy (prepubertal, perhaps) again wearing the lappa dress, nude from the waist up. The man at right, in terms of his dress, could be a marketplace worker in the 1960-62 period.

Above, McWhirter’s sole known photo of a marketplace located presumably somewhere near the ancient one held by Ndi-Onicha (though this is merely a guess). The large building at left rear might well be one of the United Africa Company (UAC) warehouses.

The map above dates to 1932, but in small print on it I show the location of the primary Onitsha Marketplace during the 1905-11 period when McWhirter was there. The marketplace photographed by McWhirter appears to be a very small one, but the picture might just show a small portion.

At left, a closer view of the market women and some of their goods. The resolution is not good enough to estimate what is contained in the bowls, but the attire of the marketwomen (and they were most likely Ndi-Onicha (or perhaps Ndi-Olu) women at this time period) looks similar to what marketwomen were wearing in Onitsha Main Market in 1960-62. (Note the small child behind the woman at the distant right, nude and head-shaved with spikey top-knots.)

Finally, the photo at left provides his single view of canoes docked at the location probably directly adjacent to and north of the 1906 Riverside marketplace. The resolution of this image is poor, but those canoes might well have been plying the Plenitude of Waters (Oru-mmili) near this location in 1960-62. And this photo appears to match the location of the famous prehistoric marketplace, Otu-Nkwo — though by this time, British Government power had transformed its situation.

Again, thanks to Helen Gee (see below):

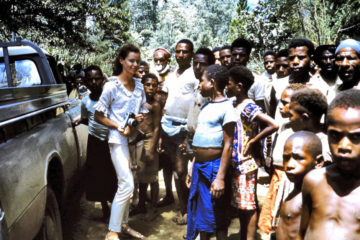

The benevolent source of all these images, Helen Gee — as I have said, granddaughter of Robert McWhirter and a career school teacher who specialized in teaching the deaf and working with students having severe reading disabilities — sent me some information about her own history as we were discussing this page. One of the things she mentioned was that when she was 20 (in 1964) she served for a time as a Red Cross Volunteer in Papua/New Guinea. She sent along some photographs of ritual performances and dances she had obtained while doing that work. I asked her about the photo at above left: was the woman holding the camera in this image some movie star who was visiting the Red Cross program at that time? No, I learned, that was Helen herself. She recently retired as Assistant Principal of a Special Education facility in a large primary school in Armidale, Australia. Both she and her husband were “long-term teachers in public schools, and are strong supporters of the public education system – the ‘crucible of democracy’.” Amen to that, and thanks again to her for reaching out to us twenty-first century advocates of Onitsha history with this new set of recordings from the very beginning of Onitsha’s “Modern Times”.

- The confluence of these two rivers produces (in 1960) a very substantial whirlpool, which Ndi-Onicha identified as an important Spirit Power (ite-ofe, lit. “soup pot”) that was thought to protect the community and was given homage in prehistoric times. [↩]

- According to its Wikipedia entry on July 18, 2016, the cummerbund was/is “an Asian-origin garment which was first adopted by British military officers in colonial India when they were exposed to Indian men wearing it. It was adopted as an alternative to a waistcoat, and later spread to civilian use. The modern use of the cummerbund among Europeans is as a component of a traditional black tie event.” [↩]

- See Henderson and Henderson 1966:28-9 for some hints regarding the irrepressibility and insouciance of Onitsha boys. [↩]

- However, when Helen and I returned briefly to Onitsha in 1992, none other than the notorious Obiekwe Aniweta was sporting a very dark one accompanying his also dark-toned Western-style suit. At the time when I commented on this innovation, he said, “Mr. Henderson, I have become a conservative!” See “Obiekwe Aniweta, Protean Man”. [↩]