Above: Peter Achukwu (at left, presenting his face as hunter-&-leopard-killer), accompanying his fellow Ogbo-Ota (Arrow Age Grade) mates as they escort the mighty Onicha Ijele on its inspection tour of Inland town, 1961.)

Mentioning the name of Peter Aniweta Achukwu seldom brought mild responses in Onitsha. The most common adjective used to describe him in Onitsha English was “wonderful,” a literal translation of an Igbo term which however did not necessarily entail the positive connotations this word normally has in English. The phrase “O di egwu” was consistently translated “He is wonderful,” but the intended meaning was the literal one, “full of wonder”, meaning “astonishing, amazing”, implying that the person will assay, and perhaps accomplish unexpected, improbable (but not necessarily desirable from the speaker’s perspective) feats.

The reference made regarding him as prone to “confusionist” tactics also connotes a heightened fear of the potential chaos associated with the introduction of uncertainty, innovation in the face of established procedures. When these words were used with reference to Achukwu, I usually sensed a combination of admiration, envy, and sometimes resentment and fear on the part of the speaker. Sometimes a person would say, “We used to fear him” (the “used to” denoting a continuing perfect tense not otherwise to be rendered in English, equivalent to the statement “It used to be cold in Jos”, referring to perceived chronic weather conditions on that plateau). There were good reasons for this exaggerated respect, for he was a most unusual man.

Born in 1901 of a very poor family, Achukwu was orphaned at an early age and his genealogical position was ambiguous. He became a house boy to Sam Nzegwu, the wealthy court clerk and contractor from Umu-EzeAroli who later became an unsuccessful kingship candidate in 1931-35, though Achukwu himself usually claimed his own lineage affiliation with Umu-Dei in Okebunabo (but often modified his genealogical stance depending on the social situation). He was educated in the early days to the level of Standard Six, and showed early promise as a “natural artist”. During his childhood he made self-employed money by constructing caps (“crowns”) for Onitsha chiefs, and in 1910 began repairing bicycles and soon founded the first bicycle and motorcycle repair shop in Onitsha.

Taken to Lagos by Nzegwu’s employment there as a contractor, he learned skills in architecture, later worked with the CMS Onitsha Industrial Mission (an early vocational training school for boys), and when it was closed the CMS sold its shop to him and he proceeded to become a private building contractor. Employed in 1927 by the United Africa Company to deliver lorries from Lagos to Onitsha for sale, he then also became a motor operator, owner, and repairer, and at the beginning of World War II he founded a motor owner’s union to compete with foreign owned transport. In many ways he was a major West-African pathfinder who innovated modes of African self assertion in entrepreneurship.

In Onitsha Achukwu actualized innovations in European derived technology. He built new types of houses, taking ideas from photographs in a magazine popular with local Europeans (West African Review) and adapting them to local conditions. During her field work in Onitsha in 1937, Sylvia Leith Ross (who was living in the second storey of one of Achukwu’s houses in the Waterside built for M. Ogo Ibeziako) reported “the visit of an architect this morning, in a tweed coat and white duck trousers,” and in whom she discovered1

an “intangible… desire for fame which was respectable…, that his work should be worthy of living”, so that in years to come people would remember the good houses built by Peter (Achukwu). Remarking on the distinctiveness of Ndi-Onicha from the rural Ndi-Igbo populations, she found notable in his views of how a house should be used the considering of such factors as “a conscious desire for privacy and repose… (on the part of, as Achukwu put it) ‘the gentlemen, those quiet men’ (who wished) a place where they could read their newspaper, or write a letter or ‘sit and think’.”

These passages suggest a strongly Westernizing, even Western intellectual orientation, and clearly Achukwu had powerfully internalized some major philosophical premises of what it meant to be a “Western Man”. One prominent episode building his reputation occurred during the 1940s when, occupying a position of some authority in the Onitsha P.W.D., he overcame what promised to become an intransigent conservative opposition to change in Enu-Onicha by running bulldozers through the Inland Town in order to create the system of roadways that converted the community to more rapid and open internal communication. The image of old mudwalled buildings (ancient Ancestral Houses, shrines, the residences of powerful local men) falling to Achukwu’s irresistable machines served as a major metaphor of his powers to further causes he deemed important to “modernization” (though I doubt that he sacrificed any places of important traditional interest, and probably very few houses overall). This willingness to outrage fellow members of the community to pursue a serious cause led many to fear him.

But over the long run (as I came to know him) Achukwu resisted becoming one of (as he called them) “those English styled men” and concentrated on incorporating certain generalized Western values he regarded as basic while simultaneously reconstructing what he considered to be a coherently “traditional” lifestyle. While he had accumulated considerable wealth, he refused to engage in such conventional displays of affluence as taking Ozo title, which had become a standard of transcendent importance for nearly all “tradition oriented” Onitsha men (i.e., those having strong interest in managing the resources controlled within the Inland Town). Instead he expended his money in a variety of innovative directions, like constructing “Achukwu’s Town Hall” in the Waterside for meetings convened by any parties living in the township, Ndi-Onicha, Ndi-Igbo, Ndi-Whatever. By doing this he accomplished what the entire Inland Town community had failed to do, namely construct an adequate “Onitsha Town Hall” (but one he proceeded to declare open to non-Indigenes as well).

In traditional activities, he focussed on participating in Age Grade 2 and “Elder Dead” (Ora-Okwute, Mmanwu, masquerade) organization) activities rather than aiming toward chieftaincy, and while doing so he brought innovative organizational ideas into the Inland Town social world.

When the 1931 kingship dispute dragged on for several years without resolution, as Peter watched his former patron and mentor Sam Nzegwu futilely dissipate his “five pots full” of buried wealth, Achukwu entered the contested arena “to show my master what his position really was” (that is, that he was being milked by his so-called supporters without significant results arising from their “support”). Together with some of his age mates, he mobilized the most active Inland Town Age Grades into a social movement that came to be called the Ogbo-Isato (“Eight Age Grades”; sometimes it was “The Seven Age Grades”, Ogbo-Isa). which helped the British colonial administrators bring the contest to an acceptable and largely popular conclusion by selecting Obi Okosi of Ogbeabu and providing him with mass support.

Following that accomplishment, he worked to establish a written “Constitution” (modelled broadly on the British Parliamentary system) for Inland Town politics, and while this effort did not come to formal fruition, it guided his own image of the meaning of Onitsha and he continued periodically to mobilize ad hoc organizations there whenever major political struggles seemed to reach an impasse and where he felt that a different, more comprehensive point of view should be purveyed.

Where, for example, he detected serious corruption in the realms of local government as the Onitsha Urban community lurched toward self-government. In this case his work exposed serious corruption on the part of Ndii-Onicha councillors ((his own people), which resulted in the dissolution of this transitional council (which had strongly favored these Indigenes). This resulted in hostility toward him among the latter (his own people), when the Colonial administrators formed a new government allowing more Non-Onitsha representatives into the council.

Achukwu’s success in these social endeavors seems to have been based on the fact that he had uncanny awareness of potential needs and sentiments among the masses of people among whom he lived: his most popular nickname, “Ochanja” (“The Inferior”), was a Township-wide appellation alluding to his tendency to give voice and strength to the will of otherwise unrepresented and powerless interests, and to break entrenched rules in order to do this. He was the main contemporary person to whom I heard people in Onitsha refer as “One who speaks for the public” (Onu ekwulu ora, or onye nekwu onu ora, “one who speaks the people’s mouth”), the traditional Ndi-Onicha Orator-spokesman.

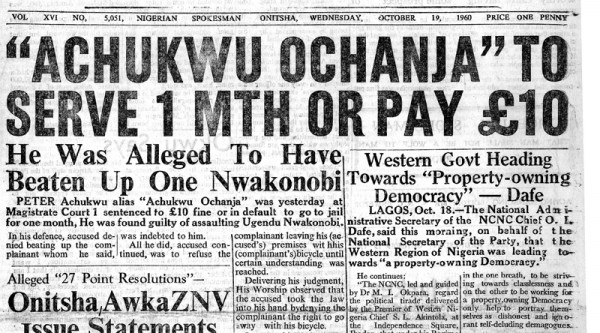

His efforts to assert his sense of justice sometimes led him into trouble with authorities. When we first arrived in Onitsha, our first encounter with him was reading the local newspaper:

But even an occasion such as this was testimonial to his local celebrity. This news account contains an unmistakable tone of wry humor in its overtly factual reporting.

But even an occasion such as this was testimonial to his local celebrity. This news account contains an unmistakable tone of wry humor in its overtly factual reporting.

The universalism associated with his social role includes what is for most Onitsha people a source of great fear: such a person, they say, will forcefully take charge of an impasse situation by “speaking truth”, even if by doing so he might reveal his own father or mother (even himself) to be “guilty”. The mind-boggling quality Onitsha people attribute to this kind of behavior seems to me to imply that it is regarded as a violation of normal human nature to behave in this way. Interestingly, upon our brief return to Onitsha in June of 1992 I heard none of the establishment elders mention his name, but when I was showing some of my 1960s photographs to a crowd of ordinary people along an Inland Town street one evening and pointed out that the man dressed as a Leopard Killer escorting the Ijele masquerade (the image below) was none other than “Achukwu Ochanja”, they responded with a spontaneous cheer. He was very recently dead at this point, as I was very saddened to discover. But of course he was around 90 years old when I died. I was also told that, near death, he agreed to take the Ozo title (which would benefit his offsrpings’ social situations), and — as death approached, he personally carved a decorated wooden coffin for his final resting place.

I first met Achukwu in January of 1961, hoping to learn more about the 1931-35 kingship dispute in which he had played so active a part, and encountered a man who typically wore a somewhat tattered and faded wrapper and singlet. I never saw him in an agbada suit, which in the early 1960s was so much de rigeur for prestige-aspiring nationalist Onitsha men that I bought two of them myself, trying (with very little success, I fear) to “fit in”. He walked with a distinct limp, said to be the result of an encounter with a leopard which he had bested in hand-to-hand mortal combat many years before, and slightly exaggerated by the fact that he always wore only one sandal and left his other foot bare. If you click on the image at left, you can clearly see the left-shoe-right-bare combination, where he is dressed as a hunter, wearing leopard-spots on his body. Fuller context for this close-up is provided in the Featured Image at the top of this page.

In conversation I was entranced by his effervescent combination of brilliantly sparkling eyes, calm energy, boundless self confidence, quick laughing good humor, and a ready tongue which spoke the truth as clearly as he saw it.

Here I think a remark on the rather poor quality of the image accompanying these comments is appropriate. The fact is I never took the opportunity to acquire a good close-up photograph of him. This shot was cropped from a group photo taken at Onyejekwe’s selection announcement. For some reason not entirely clear to me, I failed to take many closeup images of many people I encountered in Onitsha, even those I found most interesting and most hoped to remember. Consequently, writing about them later, I often have to search group photographs to obtain even as grainy a view as the one you see here, which does however manage to convey a memorable aspect of Mr. Achukwu — his unfailing good humor, here he was sighting me standing in the crowd, employing my limited camera skills to capture the moment.

An ethnographer’s delight, he enjoyed discoursing on anything that interested him, and it seemed that almost everything did, from the gardening of English flowers, or the habits of guinea fowl, to the traditional significance of cult slaves (Ndi-Osu in the pre-colonial Onitsha social order). His blunt statements might shock and startle but were never substantially disconfirmed (except for dates of past events, placement of which he sometimes confused). And despite providing me with many hours of entertaining talk, frequent invitations to share a drink of “Egg-o’-Vin”, (his apparently personal favorite among bottled drinks) and sharing with me materials from his files, he never asked anything from me, anything whatever (though I should say that few other Ndi-Onicha grownups that I dealt with did, either; most were very un-grasping while relating to us two curious, somewhat bumbling outsiders).