During 1961, Leonard Plotnicov, Richard Henderson, and Helen Kreider Henderson were advanced graduate students in Anthropology from the University of California (Berkeley) working in Nigeria, Leonard in the Northern Nigerian town of Jos and the Hendersons in Onitsha in the southeastern part of the country. Leonard was invited by one of his friends in Jos, an Opobo man named Samuel Bel-Gam, to visit Opobo town to witness New Year festivities there, and Leonard arranged to have the Hendersons also join him there as guests. Opobo people, natives of a community of Ijaw-speaking people who had lived prior to British Colonial times on the southern coast of the Niger Delta, expressed great pride in their native traditions and enjoyed displaying annual festivities that celebrated their glorious past.

Note: after an earlier edition of this website was published, we received communications from Ms. Boma Fubera, a native of Opobo town (now a Research Assistant in Radiology at Duke Univeristy in North Carolina) who was eight years old when we visited. She kindly provided informative comments about our images, and I have inserted these into the text, hopefully noting this with her initials [B.F.]. Many thanks to her for her interest in the website and her knowledge of Opobo.

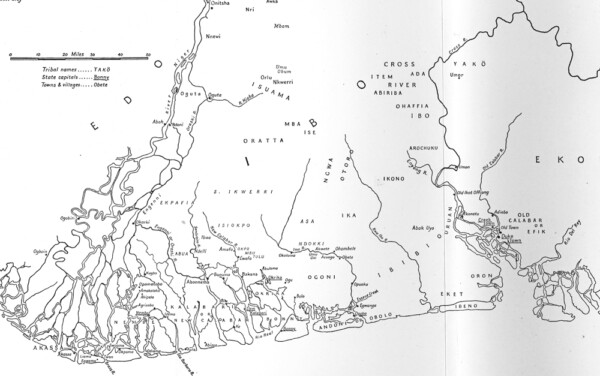

Below, a map of the “Oil Rivers” region stretching along the Nigerian coast south of Onitsha (shown at the top). The coastal riverways are very complex and considerably interwoven in the swmplands of the Delta.

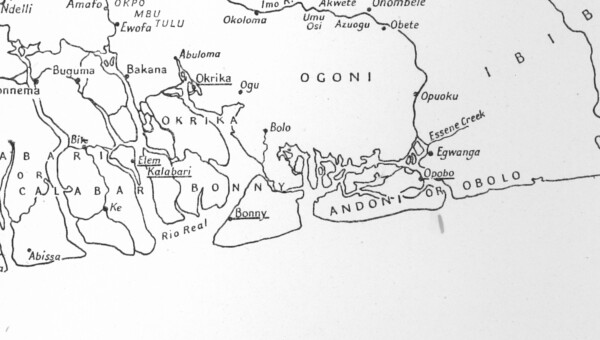

The three of us mobilized our two-car caravan in Onitsha and drove to the town of Bori (east of Pt. Harcourt along the creeks of the Niger Delta), where a ferry would carry us across the Imo River to Opobo. In the map below, Opobo appears toward lowerr right in the image.

At the end of this essay, I will insert a historical sectigon that discusses this larger area, including the distinctive placeof Opobo. Helen and I knew almost nothing about this history when we arrived here, but we found it memorable and we learned a lot about the distinctiveness and energy of Opobo people.

Bori pier still stands today near the head of a sinuous creek that feeds into the Imo River. In 1961 the ferry departing from the end of the mainland road docked at this site, negotiating this creek before entering the open waters of the Imo River estuary. As in 1961, today road access is limited to the eastern side of the river, to the location labeled below “Industrial” Opobo, a site now containing an aluminum smelter complex named after the Ibibio town to the east. (Today this is part of the Ibibio-dominated Akwa Ibom State.) The Opobo we were visiting was the original community, located on the west bank of the river further south and marked by a blue square on this satellite map below. Today this is part of Nigeria’s Rivers State, while the land across the river to the east is in Akwa Ibom State. (Thanks to Google Earth and the other companies indicated for this 2008 image.) Other current images indicate an oil field now located at the mouth of Imo River at map bottom.

In 1961, what we label here “Industrial” Opobo was called by Opobo people “Egwanga Opobo”, and was the main site of market trade (including palm oil), district administration, and boat construction. Many Opobo people lived and worked there, along with Igbo and Ibibio people. [pc B.F., see Sources. According to this source (Ms. Fubara), “The name Egwanga is a corruption of the old Ibani (Ijaw) language. The original term was Igwuanga which means “those hillsides”. You see from Opobo Town’s point everything is more elevated. As one approaches Egwanga from Opobo Town, one sees the red clay hill rising from the waterside, at least that is what I saw as a child.”]

Below, as the ferry was negotiating the creek, one of the Opobo War-Canoe teams came driving by:

This dugout canoe was a contemporary version of a pre-colonial canoe, which was (in the words of G.I. Jones, describing the form as it was during the 19th century) “a large dug-out… armed with cannon fore and aft which were lashed to the thwarts and it occasionally carried another on a swivel amidships. The fifty or more paddlers now carried muskets….” ( (Sources, p. 55)) Contemporary teams like the one shown here are unarmed (and recruited by different criteria than in former times) but attempting to operate according to Canoe House traditions of performance. The banner on this canoe reads “Ofo na ogu”, meaning (in Igbo ) they have some ritual powers/protections. [p.c.B.F.]

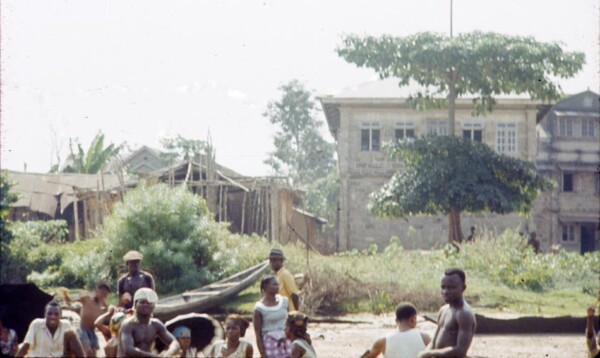

We then saw Opobo Town at a distance from across Imo River:

As we approached, various multi-story buildings became visible. Most of these large, iron-roofed structures were built during 19th-century boom times of the city. And most were, for most of the year in 1961, largely unoccupied.

On closer view, one could see that some buildings were of more recent construction, as the pair at right, below:

The most striking building in Opobo town was King JaJa’s palace, below, which he had ordered prefabricated in England. It was now entirely unoccupied. JaJa’s compound, its central courtyard and some of its encompassing buildings shown below, was Opobo’s largest, while a number of smaller compounds ranged around it repeated this pattern at smaller scales. These were physical reflections of social groups making up traditional Opobo society, called Canoe Houses.

During the 19th century, a Canoe House was a dynamic organization, composed of a number of households, each comprising a man, his wife or wives, his children, servants, slaves and other dependants attached to him. A group of these composite households formed a Canoe House when its leader, having spawned or purchased enough dependants capable of manning a war canoe and mobilized enough wealth to engage in necessary militant activities, was recognized by other chiefs and the king as having “filled his war canoe”, and became a chief in his own right.

The terminology of “house” and “compound” is likely to be confusing to outsiders. According to [pc B.F.], Ms. Fubara, “The way I would describe the terms ‘compound’ and ‘house’ as I have been using them, would allude to the Ijaw erms of ‘polo’ and ‘wari’ , where ‘polo’ is quite literally a compound of different ‘wari’s. ‘Wari’ also means individual houses, but depending on the context, it also means a household or homestead if you will, for a particular clan. So the polo/compound is presided over by a main chief, and the waris/houses by fellow chiefs who may be considered as secondary chieftaincies. These houses are most likely war canoe houses in which case the chiefs were prosperous enough to outfit and man war canoes.”

While JaJa’s compound was the largest, the town was carved into a number of them. Viewed across rooftops, you can see several basically rectangular outlines below. The flag rising over rooftops at left-center represents one Canoe House.

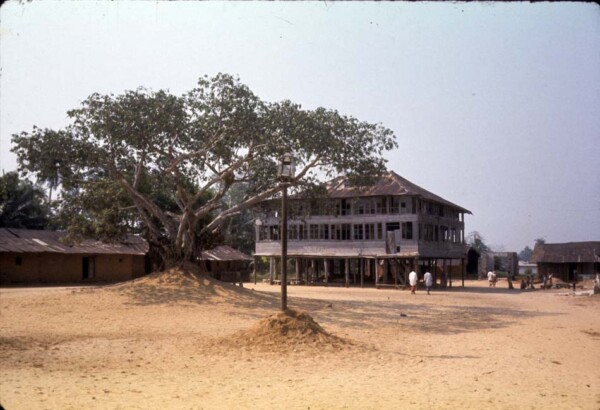

The Canoe House as settlement consisted of a walled compound entered through a gate, shown below. The main House within it stands here at right, raised off the ground on pillars, with living quarters mainly on the upper floor. I was told that the house inside is the Omubo Pepple house, within the larger Pepple compound. In former times every compound of this kind had a protective gate. [p.c.B.F.]

This one below shows the basic pattern most clearly, with living quarters above and storage level below, the whole presenting a fortified structure to outsiders. I was told that this house belonged to Chief Oko Jaja, a subordinate chief to King Jaja [p.c.B.F.’s brother].

The tomb statue in this compound below was dedicated to Warribe Uranta, born in Bonny in 1859.

this smaller compound below was dominated by a single figure., a monument to Chief Peterside [B.F.]. (Note the style of lamp poles bracketing the figure. Poles of this type were scattered widely through the town. None we saw was currently lit.)

This one bore the label,

This Monument

And Statue

Is erected in the memory of

The late

SUNJU PETERSIDE

Of Opobo

Who was born at Ayamma

On the

Sixth Day of September 1859

And died on the

21st Day of December 1925

This compound below had several memorial structures, and also shrines. I was told that this was the main House of Ogolo compound [p.c.B.F.]. Concrete blocks lined along the ground were presumably for use in building construction at left.

Mr. Bel-Gam (part of the Cookey House) and his family, our hosts, housed us very comfortably in their own home, below, the fine brick house in the background, and immediately found native dress for us and showed us how to clothe ourselves in appropriate fashion. Women of the household took particular care getting Helen’s clothing right. This house belonged to Mr. Eustace Jaja, seen here standing just behind Helen. [pc B.F.] He and the others shown here treated us with great hospitality.

We then went off to church, along the town’s neatly curving walkways.

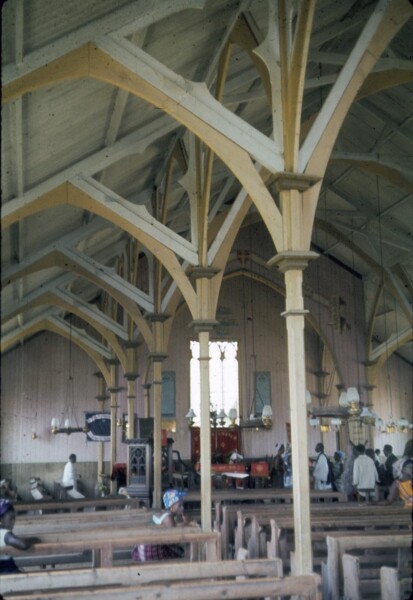

St. Paul’s Church, part of Niger Delta Pastorate of the Church Missionary Society (CMS), was prefabricated of iron and wood by an English firm in Liverpool during 1906, reassembled in Opobo in 1907. It is now quite venerable, not much to look at outside (but see further below!):

B elow, our party met the Amanyanabo (King) of Opobo in front of the church prior to service. Here you see Helen wearing the epitome of proper native dress according to our hosts’ standards. Of all the people we saw in Opobo during our visit (with the sole exception of the man standing behind, in the doorway), the Amanyanabo was the only adult person who did not wear the native attire, dressing instead in an impeccably formal English “suit”. Our host Mr. Jaja stands at the Amanyanabo’s right. [Mr. Ngozi Fubara stands just behind Helen and Leonard, and Mr. Denne Finebone stands at far right in the church doorway. [pc B.F.]]

Below, Dick and Leonard wore close approximations to correct native dress, in particular imported light-flannel dress shirts with extremely long tails and colorful wrappers below. The man at left is not quite correct in that regard, but he is closer to it than Mr. Bell-gam, who dressed in a lighter-textured, short-sleeved shirt. Mr. Jaja at far right.

Entering church for service, we were wholly unprepared for the soaring and elegant beauty of its interior (note: dust marks apparent on pillars etc. are products of poor photographic slide storage over some 47 years, not part of the building):

Seating arrangements in church placed women at left and men at right. Seats allocated to chiefs are seen most clearly in the image above, where the man in white at left rear is momentarily sitting. Our party was allocated places there, and no chiefs joined us on this particular day. The Amanyanabo sat in a separate chair in the aisle just below the pulpit. (In the image below, the woman in the green-chevroned wrapper and white blouse is Esther Fubara [pc B.F.].

As the minister began his address to the congregation from the pulpit, the Amanyanabo began addressing us in an even louder voice, asking us how our visit was going, what we had been doing since our arrival, etc. Startled by this unexpected, competing side commentary, we answered in very brief terms. Shortly thereafter, he arose and casually trotted down the aisle (at left, above) and out the front door, jogging back soon thereafter to take his seat again.

This was rather startlling royal behavior, but a little thought clarified it for me: the king alone among his subjects is truly “free”, meaning he is not constrained by the socially normative rules that others are expected to follow. For me, this was strikingly different from the behavior I had witnessed in the Onitsha Obi, traditionallly such a secluded, behaviorally constrianed monarch. (But perhaps I had seen too few occasions. I was told that sometimes Obi Okosi II would just start to laugh, for no apparent reason, whereupon those around him would have to laugh also. There are no doubt many ways of asserting royal perrogatives.)

Meanwhile the minister continued addressing his congregation, mainly discussing what he saw as the extremely decrepit condition of the present church building and calling for its replacement with a new, more “modern” building. He held up as an impressive example the huge, concrete-block church currently being built in the town of Owerri (in Igboland, well to the north). We had seen this structure ourselves, and it was a very massive building indeed, but extremely ungainly as an architectural form in comparison to the present place of worship in our eyes. Beauty was clearly in the eyes of the beholder. (Today, the wondrous Liverpool prefab is indeed long gone, replaced by a concrete-block structure. [pc B.F.])

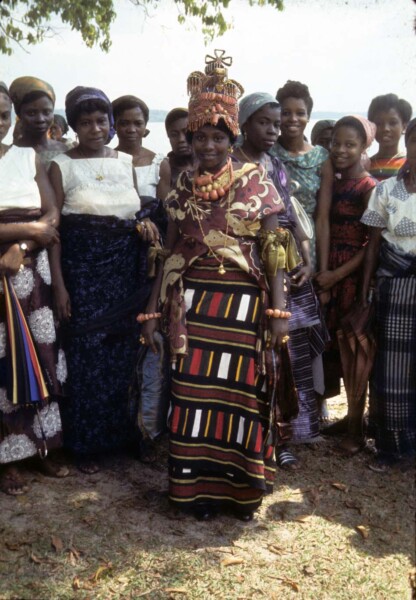

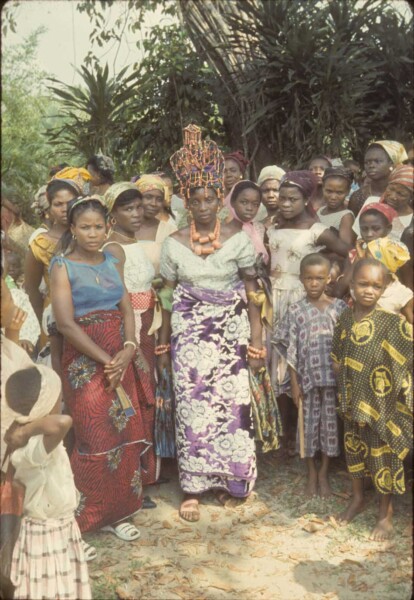

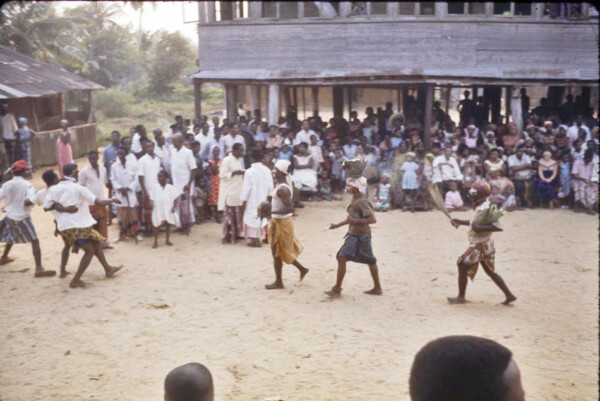

Later that day, we saw ritual culminations for two newly-marriage-eligible young women, being brought out from the seclusion which European Colonial observers had called the “Fattening House”, a misleadingly negative stereotype of an educational process where girls were separated from males and secluded among knowledgeable female elders, trained in arts of cooking and household management, beautification, sexual pleasure, child bearing, and other marriage skills, and were now ready to re-appear in public view. We understand that the two young women photographed below as they were emerging from the process (these females are called /Iriabo/ by Opobo people) come from the Fubara compound, historically composed of seven Opobo canoe houses. The women who were escorting them come from two different canoe houses in the Fubara compound. [pc B.F.]

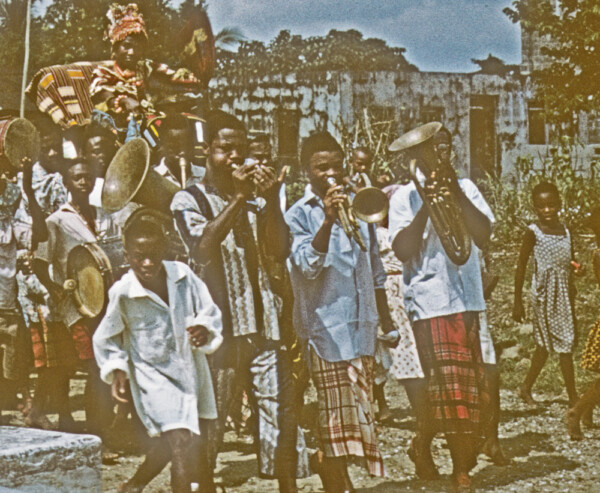

The dress of these young women was, of course, set to the richest level of opulence available to their families. Each woman was then paraded out into public grounds by a group of her House members [the buildings here are part of the Fubara Compound] [pc B.F.]:

This group led their maiden out into the public space. Note the impressive orchestra leading the way.

This public space displayed an array of old Portuguese cannons (large warship-size) proclaimed the primary locus of civic power:

Where the central figure is the overlooking statue of King JaJa, raised up and dedicated under British Colonial adminstration aegis, praising the King as a great early leader:

We posed below-statue after the procession departed. While the Colonial-era statue pediment presented, on the facade of the pedestal, a profoundly-sanitized version of the King’s relationship with the British,

The red sign to the right above, raised up along with Nigeria’s 1960 Independence, reads differently:

Historic Monument

Erected to the Memory of

His Late Majesty

King Jaja of Opobo, Nigeria WCA

1821-1891

Grandfather of

His Highness the Amanyanabo of Opobo

Chief The Hon. Douglas Jaja.

King Jaja Was a Great Nationalist, Soldier

And Explorer. His History is Interwoven with the

Early Growth of Trade and Politics

And With the Founding of Opobo Town

In 1870.

He Was the First African Ruler to Oppose British

Imperialism in West Africa. Defending the course

Of the Independence of His Country, He Was

Kidnapped by British Imperialists in

And Died in harness in 1891 in Teneriffe.

Erected to the Memory of

Jaja, King of Opobo

Born 1821 Died 1891

………………………………………………..

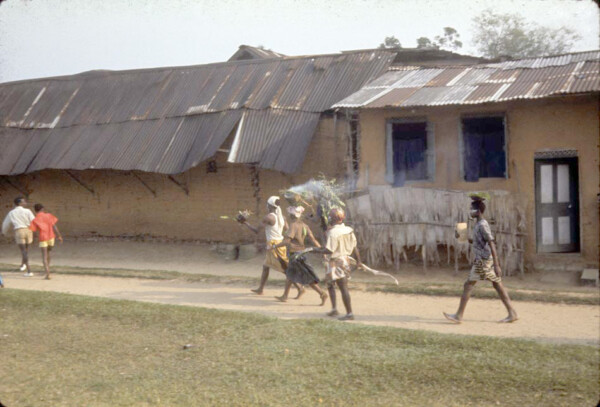

Early afternoon, preceding the city’s annual contest among the “dance troupes”, men associated with various teams carrying Juju objects could be seen walking along its streets, below. (The house here is the outside of Sam Annie Pepple house also part of the greater Pepple compound (see further below) [p.c.B.f.].

A closer view of this fire-magic bearer and his team. He strides along in a very purposeful manner. Such figures punctuate the ordinary with a strong sense of uncanny presence, adding a very dramatic touch to the moment.

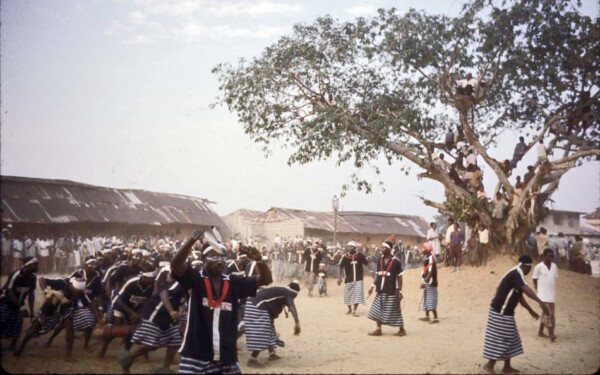

The passage of such figures generally announced an approaching “Dance Troupe” (in this image below, the same “Ofo na Ogu” troupe shown in the canoe, above), who stopped along their way to salute various relatives as they proceeded toward the palace:

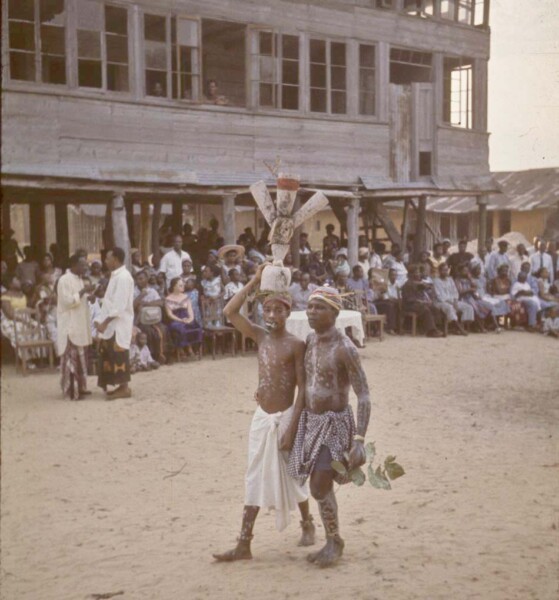

At JaJa’s palace (below),, crowds dressed in finery were seated to observe the dancing contest, as Juju men brought their wares into the arena — note the man with the red cap walking here :

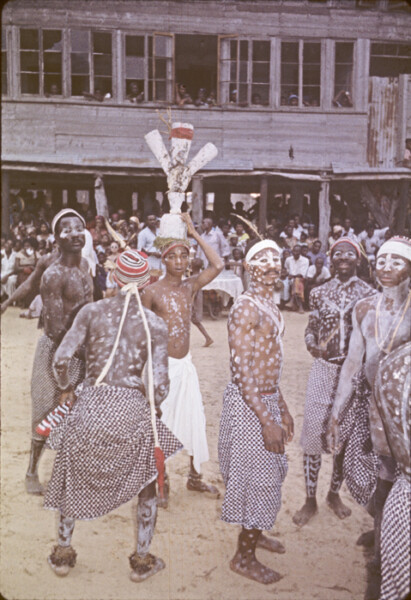

Below, spectators and judges sat at beneath JaJa’s palace as Dance Troupes Teams began to enter. The judge’s table is visible here directly behind what we called the Leopard-spots Team’s juju men. (This Troupe was called Ogelemkpa, [p.c. B.F.] [Helen (wearing a very beautiful dress we unfortunately failed to photograph close up) sits left of the judges’ seats. The following is Ms. Fubara’s commentary on the nature of these teams: [p.c. B.F.] “In dealing with the dance groups, the term troupe is actually appropriate. These groups are not particularly attached to any individual polo or wari and therefore cannot be categorized as belonging to any war canoe house. They may have originated from individual compounds, but are no longer that way, not even when I was there [Ms. Fubara left Nigeria in 1969 at age 16.]. The groups are open to the population as a whole to join whichever one they prefer. Even though on the 31st of December they come into town in long canoes, these are mainly ceremonious, they are team canoes but do not belong to any particular chief or wari or compound. Actually, the native word to describe each troupe is ‘uke’. The word uke really means a close group of friends or mates participating in similar activities.” [Thanks again to Ms. Fubara for adding these commentaries.]

Below, the Ugelemkpa Troupe [B.F.] dances around the royal square. Lead members carry their rolled-up red flag above their knees. You can see the flag — look behind the Juju man carrying his medicine. It’s red.

Below, the Ejesilem troupe [B.F.] dances before the palace….

In the image below, note details of this fine Troupe (and also the unusual cap of the Juju man at near left). This troupe, again, is the same Ofo Na Ugo Troupe we saw earlier [p.c.F.B.].

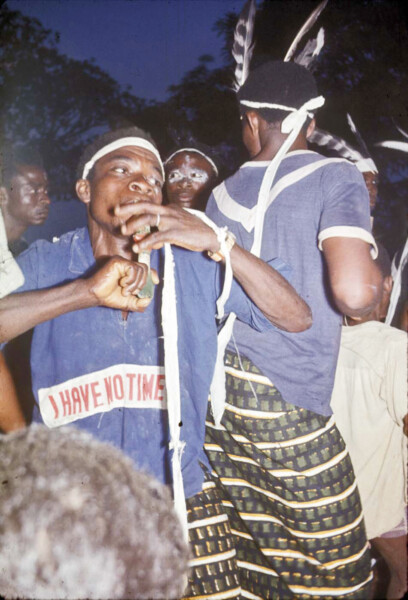

As the sun went down and things began to darken, below, this group also dressed in blue and white, but without a cap and wearing a distinctive wrapper. (I’ll call them the “I HAVE NO TIME” group.)

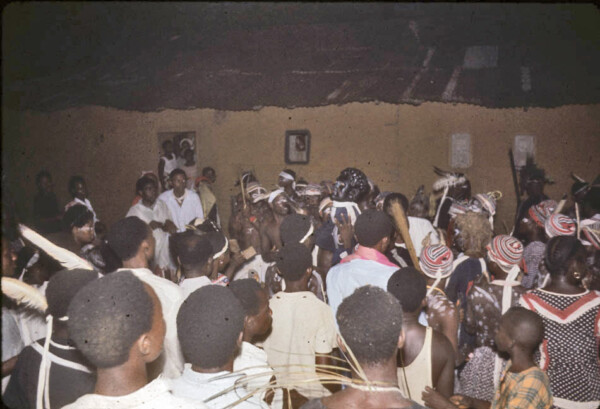

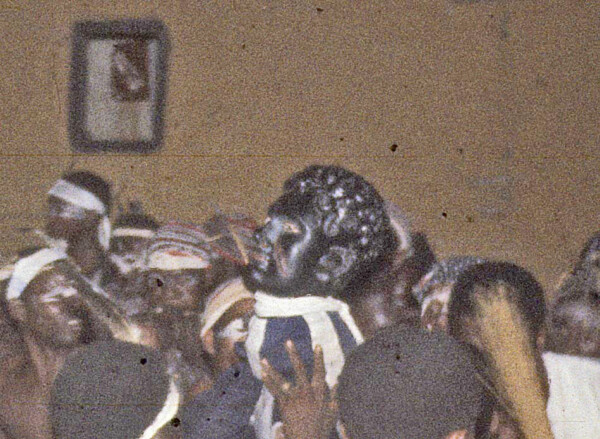

Following the parade of Canoe House teams, as darkness fell, the final ritual we observed was what we will call a Twilight Struggle on the Roof, which involved two figures, one of them very distinctly in madquerade:

The struggle culminated with the masked figure below being brought down into the standing crowd:

Below, a closeup view of this figure;s “head”:

the face looks to me like a black Greek God. A very thought-provoking end in this darkness.

Our best Opobo source, Ms. Fubbara, tells me that this figure , and that she (8 years old at the time) was warned by her family that if she did not improve her behavior, he would come and take her away. [F.B.]

………………………………………………

Our visit to Opobo was brief after this climactic nocturnal moment. Our hosts were busy with their many meetings, and we took our departure with great gratitude, thinking we would never forget our visit to Opobo Town (as has proved entirely true over the many years since, indeed every time we revisit the record new details emerge).

We have not thought previously to mention a major feature of this experience: the bounteous and indescribably delicious, fiery-spiced food provided us by our female hosts (sucking the meat out of periwinkles in stew was a unique delight to our palates), whose repeated disapproval of our limited stomach capacities was perhaps the sole negative note struck during the entire journey. Thanks again, to these wonderful master chefs (seen below, with their charge, Helen)!

And a note of thanks to the (to us, previously unknown) periwinkle sea snail, ….

……………………………………………

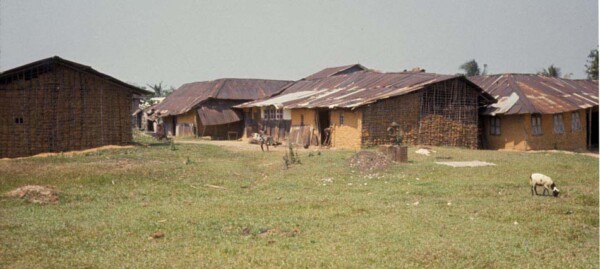

Below, as we were leaving, we noticed that sheep acted as continual grazers, maintaining the well-manicured, close-cropped quality of grasses everywhere. (Note also traditional “wattle-and_daub” methods of wall construction, using a weave of vertical and horizontal poles, then covered with adobe mud. The wall structures have been exposed by erosion in two buildings at left and center.)

Below, we see buildings belonging to Siminialayi family, here seen from the landward side as we prepare to depart: [pc B.F.]

Below, again on our ferry, we look back at the weather-beaten exterior of a marvelous historical city. (The central, storaey-building, is part of chief Eppele’s compound. [B.F.]

Finally, below, a view of some fellow Creek travelers as the ferry took us back toward Bori:

A brief historical account of Opobo and Vicinity

As historian Kenneth Dike has shown (see Sources), this entire Delta region was little inhabited before European traders came to the coast in the early 1500s (the soil is very poor for farming), but by the 1830s it had become the greatest single trading area in West Africa, dominated for several centuries by the Ijaw Kingdom of Bonny (bottom center on the Jones map above). While early trade was mainly in slaves, during the 19th century palm oil became the dominant export. Prior to the late 1860s, the people of Opobo lived in and were members of the Bonny Kingdom, so our story must start there.

Bonny’s power base was a military organization in which the king and his council of chiefs were each independent traders, operating a navy of cannon-bearing war canoes, each chief supplying at least one armed canoe with crew. Some of these canoes were large enough to carry more than a hundred musket-armed warriors, and during the early 19th century this team of war canoes both gained a monopoly over products of the interior and was able to dictate terms of trade with the European merchants visiting the coast.

In the late 1860s, dispute among Bonny’s ruling families brought civil war, and one faction, led by a military, political, and economic genius named JaJa, abandoned that town, having identified a militarily and economically strategic position at the mouth of the Imo River, and established a center there which became the trading state of Opobo. So successful was JaJa’s leadership that the Opobo settlers quickly replaced Bonny in controlling and expanding interior oil markets (the Imo River being the main corridor inland), and in 1873 they obtained a treaty with England stating that English merchants trading with Opobo could only do so at the port of Opobo Town, and giving JaJa the right to intercept and fine them if they tried to bypass him and enter the interior.

But very soon, expanding European commercial ambitions brought intense conflict with JaJa, and in 1887 the British seized and imprisoned him in Teneriffe (Canary Islands), where he died in 1891. Opobo traders adapted well to their changed situations for a time, but when the world economic depression struck in the 1930s they were financially ruined, and most Opobo people had to emigrate to other parts of Nigeria for economic opportunities. Having taken advantage of their earlier contacts with Europeans, they had pioneered in western education (a Christian school opened in Opobo in 1874), acquired professional skills very early, then settled in other parts of Nigeria as strangers, becoming eventually leading members of the new Nigerian elite, but (as nationalism and interethnic competition erupted in the 1950s) they occupied increasingly uncertain positions in what then became independent Nigeria. This was their situation in 1961 when we visited Opobo.

When Leonard discussed their situation with Opobo people living and working in the Northern Nigerian tin-mining center at Jos, he found them intensely concerned with the preservation of Ijaw culture, and dedicated to the goal of reviving their home town, which for most of the year was now practically a “ghost town”, with a care-taker population ranging somewhere around 300 people. They were especially concerned that their children learn to speak Ijaw as opposed to English, and to re-experience cultural features of times past, including wearing native styles of dress and performing the roles of canoe-team warriors.

…………… THIS IS THE END OF THE ENTIRE PAGE. ALL CONTENT BELOW IS REDUNDENT; I WILL DELETE IT WHEN I FIGURE OUT HOW TO DO SO.

this sm

This group led their maiden out into public space where an array of old Portuguese cannons proclaimed the locus of civic power:

That is, the overlooking statue of King JaJa, raised up and dedicated under British Colonial adminstration aegis, praising the King as a great early leader:

We posed below-statue after the procession departed. While the Colonial-era statue pediment presented a much-sanitized version of the King’s relationship with the British,

the red sign to the right above, raised up along with Nigeria’s 1960 Independence, reads differently:

Historic Monument

Erected to the Memory of

His Late Majesty

King Jaja of Opobo, Nigeria WCA

1821-1891

Grandfather of

His Highness the Amanyanabo of Opobo

Chief The Hon. Douglas Jaja.

King Jaja Was a Great Nationalist, Soldier

And Explorer. His History is Interwoven with the

Early Growth of Trade and Politics

And With the Founding of Opobo Town

In 1870.

He Was the First African Ruler to Oppose British

Imperialism in West Africa. Defending the course

Of the Independence of His Country, He Was

Kidnapped by British Imperialists in

And Died in harness in 1891 in Teneriffe.

Erected to the Memory of

Jaja, King of Opobo

Born 1821 Died 1891

Early afternoon, preceding the city’s annual contest among the “dance troupes”, men associated with various teams carrying Juju objects could be seen walking along its streets. (The house here is the outside of Sam Annie Pepple house also part of the greater Pepple compound (see further below) [p.c.B.f.].

Opobo December Solstice Visit 1961

By Leonard Plotnicov, Richard Henderson, and Helen Kreider Henderson

(For sources used and contact information, see the bottom of the page.)

[Note: Click on each image to enlarge it!]

During 1961, Leonard Plotnicov, Richard Henderson, and Helen Kreider Henderson were advanced graduate students in Anthropology from the University of California (Berkeley) working in Nigeria, Leonard in the Northern Nigerian town of Jos and the Hendersons in Onitsha in the southeastern part of the country. Leonard was invited by one of his friends in Jos, an Opobo man named Samuel Bel-Gam, to visit Opobo town to witness New Year festivities there, and Leonard arranged to have the Hendersons also join him there as guests. Opobo people, natives of a community of Ijaw-speaking people who had lived prior to British Colonial times on the southern coast of the Niger Delta, expressed great pride in their native traditions and enjoyed displaying annual festivities that celebrated their glorious past.

So the three of us mobilized our two-car caravan in Onitsha and drove to the town of Bori (east of Pt. Harcourt along the creeks of the Niger Delta), where a ferry would carry us across the Imo River to Opobo. The map below, adapted from G.I. Jones 1963 (see Sources), provides the 19th-century historical basis for the location we sought: Opobo Town is shown here near the mouth of the Imo River at bottom right-center on this map.

As historian Kenneth Dike has shown (see Sources), this entire Delta region was little inhabited before European traders came to the coast in the early 1500s (the soil is very poor for farming), but by the 1830s it had become the greatest single trading area in West Africa, dominated for several centuries by the Ijaw Kingdom of Bonny (bottom center on the Jones map above). While early trade was mainly in slaves, during the 19th century palm oil became the dominant export. Prior to the late 1860s, the people of Opobo lived in and were members of the Bonny Kingdom, so our story must start there.

Bonny’s power base was a military organization in which the king and his council of chiefs were each independent traders, operating a navy of cannon-bearing war canoes, each chief supplying at least one armed canoe with crew. Some of these canoes were large enough to carry more than a hundred musket-armed warriors, and during the early 19th century this team of war canoes both gained a monopoly over products of the interior and was able to dictate terms of trade with the European merchants visiting the coast.

In the late 1860s, dispute among Bonny’s ruling families brought civil war, and one faction, led by a military, political, and economic genius named JaJa, abandoned that town, having identified a militarily and economically strategic position at the mouth of the Imo River, and established a center there which became the trading state of Opobo. So successful was JaJa’s leadership that the Opobo settlers quickly replaced Bonny in controlling and expanding interior oil markets (the Imo River being the main corridor inland), and in 1873 they obtained a treaty with England stating that English merchants trading with Opobo could only do so at the port of Opobo Town, and giving JaJa the right to intercept and fine them if they tried to bypass him and enter the interior.

But very soon, expanding European commercial ambitions brought intense conflict with JaJa, and in 1887 the British seized and imprisoned him in Teneriffe (Canary Islands), where he died in 1891. Opobo traders adapted well to their changed situations for a time, but when the world economic depression struck in the 1930s they were financially ruined, and most Opobo people had to emigrate to other parts of Nigeria for economic opportunities. Having taken advantage of their earlier contacts with Europeans, they had pioneered in western education (a Christian school opened in Opobo in 1874), acquired professional skills very early, then settled in other parts of Nigeria as strangers, becoming eventually leading members of the new Nigerian elite, but (as nationalism and interethnic competition erupted in the 1950s) they occupied increasingly uncertain positions in what then became independent Nigeria. This was their situation in 1961 when we visited Opobo.

When Leonard discussed their situation with Opobo people living and working in the Northern Nigerian tin-mining center at Jos, he found them intensely concerned with the preservation of Ijaw culture, and dedicated to the goal of reviving their home town, which for most of the year was now practically a “ghost town”, with a care-taker population ranging somewhere around 300 people. They were especially concerned that their children learn to speak Ijaw as opposed to English, and to re-experience cultural features of times past, including wearing native styles of dress and performing the roles of canoe-team warriors.

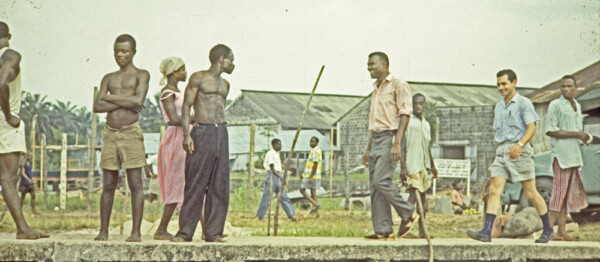

Below, Leonard (at right wearing shorts) and his friend Samuel Bel-Gam (wearing the pink dress-shirt) arranged our ferry transportation from the creek-side pier at Bori.

Bori pier still stands today near the head of a sinuous creek that feeds into the Imo River. In 1961 the ferry departing from the end of the mainland road docked at this site, negotiating this creek before entering the open waters of the Imo River estuary. As in 1961, today road access is limited to the eastern side of the river, to the location labeled below “Industrial” Opobo, a site now containing an aluminum smelter complex named after the Ibibio town to the east. (Today this is part of the Ibibio-dominated Akwa Ibom State.) The Opobo we were visiting was the original community, located on the west bank of the river further south and marked by a blue square on this satellite map below. Today this is part of Nigeria’s Rivers State, while the land across the river to the east is in Akwa Ibom State. (Thanks to Google Earth and the other companies indicated for this 2008 image.) Other current images indicate an oil field now located at the mouth of Imo River at map bottom.

In 1961, what we label here “Industrial” Opobo was called by Opobo people “Egwanga Opobo”, and was the main site of market trade (including palm oil), district administration, and boat construction. Many Opobo people lived and worked there, along with Igbo and Ibibio people. [pc B.F., see Sources. According to this source (Ms. Fubara), “The name Egwanga is a corruption of the old Ibani (Ijaw) language. The original term was Igwuanga which means “those hillsides”. You see from Opobo Town’s point everything is more elevated. As one approaches Egwanga from Opobo Town, one sees the red clay hill rising from the waterside, at least that is what I saw as a child.”]

Below, a view of boats on the creek from near the ferry pier. Helen stood waiting at lower right.

Below left, another view of canoe travelers from pier side; below right, a view from the ferry as we embarked.

As the ferry was negotiating the creek, one of the Opobo War-Canoe teams came driving by:

This dugout canoe was a contemporary version of a pre-colonial canoe, which was (in the words of G.I. Jones, describing the form during the 19th century) “a large dug-out… armed with cannon fore and aft which were lashed to the thwarts and it occasionally carried another on a swivel amidships. The fifty or more paddlers now carried muskets….” (Sources, p. 55) Contemporary teams like the one shown here were unarmed (and recruited by different criteria than in former times) but attempting to operate according to Canoe House traditions of performance. The banner on this canoe reads “Ofo na ogu”, meaning (in Igbo) some ritual powers/protections. [p.c.B.F.]

We then saw Opobo Town at a distance from across Imo River:

As we approached, various multi-story buildings became visible. Most of these large, iron-roofed structures were built during 19th-century boom times of the city. And most were, for most of the year in 1961, largely unoccupied.

On closer view, one could see that some buildings were of more recent construction, as the pair at right, below (belonging to the Siminialayi family) [pc B.F.].

The most striking building in Opobo town was King JaJa’s palace, below, which he had ordered prefabricated in England. It was now entirely unoccupied. JaJa’s compound, its central courtyard and some of its encompassing buildings shown below, was Opobo’s largest, while a number of smaller compounds ranged around it repeated this pattern at smaller scales. These were physical reflections of social groups making up traditional Opobo society, called Canoe Houses.

During the 19th century, a Canoe House was a dynamic organization, composed of a number of households, each comprising a man, his wife or wives, his children, servants, slaves and other dependants attached to him. A group of these composite households formed a Canoe House when its leader, having spawned or purchased enough dependants capable of manning a war canoe and mobilized enough wealth to engage in necessary militant activities, was recognized by other chiefs and the king as having “filled his war canoe”, and became a chief in his own right.

The terminology of “house” and “compound” is likely to be confusing to outsiders. According to [pc B.F.], Ms. Fubara, “The way I would describe the terms ‘compound’ and ‘house’ as I have been using them, would allude to the Ijaw erms of ‘polo’ and ‘wari’ , where ‘polo’ is quite literally a compound of different ‘wari’s. ‘Wari’ also means individual houses, but depending on the context, it also means a household or homestead if you will, for a particular clan. So the polo/compound is presided over by a main chief, and the waris/houses by fellow chiefs who may be considered as secondary chieftaincies. These houses are most likely war canoe houses in which case the chiefs were prosperous enough to outfit and man war canoes.”

While JaJa’s compound was the largest, the town was carved into a number of them. Viewed across rooftops, you can see several basically rectangular outlines below. The flag rising over rooftops at left-center represents one Canoe House.

The Canoe House as settlement consisted of a walled compound entered through a gate, shown below. The main House within it stands here at right, raised off the ground on pillars, with living quarters mainly on the upper floor. The house inside is the Omubo Pepple house, within the larger Pepple compound. In former times every compound of this kind had a protective gate. [p.c.B.F.]

This one below shows the basic pattern most clearly, with living quarters above and storage level below, the whole presenting a fortified structure to outsiders. This house belonged to Chief Oko Jaja, a subordinate chief to King Jaja [p.c.B.F.].

The tomb statue in this compound below was dedicated to Warribe Uranta, born in Bonny in 1859.

this smaller compound below was dominated by a single figure. (Note the style of lamp poles bracketing the figure. Poles of this type were scattered widely through the town. None we saw was currently lit.)

This one bore the label,

This Monument

And Statue

Is erected in the memory of

The late

SUNJU PETERSIDE

Of Opobo

Who was born at Ayamma

On the

Sixth Day of September 1859

And died on the

21st Day of December 1925

This compound below had several memorial structures, and also shrines. This was the main House of Ogolo compound [p.c.B.F.]. Concrete blocks lined along the ground were presumably for use in building construction at left.

Mr. Bel-Gam (part of the Cookey House) and his family, our hosts, housed us very comfortably in their own home, below, the fine brick house in the background, and immediately found native dress for us and showed us how to clothe ourselves in appropriate fashion. Women of the household took particular care getting Helen’s clothing right. This house belonged to Mr. Eustace Jaja, seen here standing just behind Helen. [pc B.F.] He and the others shown here treated us with great hospitality.

We then went off to church, along the town’s neatly curving walkways.

St. Paul’s Church, part of Niger Delta Pastorate of the Church Missionary Society (CMS), was prefabricated of iron and wood by an English firm in Liverpool during 1906, reassembled in Opobo in 1907. It is now quite venerable, not much to look at outside (but see further below!):

Our party met the Amanyanabo (King) of Opobo in front of the church prior to service. Here you see Helen wearing the epitome of proper native dress according to our hosts’ standards. Of all the people we saw in Opobo during our visit (with the sole exception of the man standing behind, in the doorway), the Amanyanabo was the only adult person who did not wear the native attire, dressing instead in impeccably formal English style. Mr. Jaja stands at the Amanyanabo’s right. [Mr. Ngozi Fubara stands just behind Helen and Leonard, and Mr. Denne Finebone stands at far right in the church doorway. [pc B.F.]]

Below, Dick and Leonard wore close approximations to correct native dress, in particular imported light-flannel dress shirts with extremely long tails and colorful wrappers below. The man at left is not quite correct in that regard, but he is closer to it than our host, who dressed in a lighter-textured, short-sleeved shirt.

Entering church for service, we were wholly unprepared for the soaring and elegant beauty of its interior (note: dust marks apparent on pillars etc. are products of poor photographic slide storage over some 47 years, not part of the building):

Seating arrangements in church placed women at left and men at right. Seats allocated to chiefs are seen most clearly in the image above, where the man in white at left rear is momentarily sitting. Our party was allocated places there, and no chiefs joined us on this particular day. The Amanyanabo sat in a separate chair in the aisle just below the pulpit. (In the image below, the woman in the green-chevroned wrapper and white blouse is Esther Fubara [pc B.F.].

As the minister began his address to the congregation from the pulpit, the Amanyanabo began addressing us in an even louder voice, asking us how our visit was going, what we had been doing since our arrival, etc. Startled by this unexpected, competing side commentary, we answered in very brief terms. Shortly thereafter, he arose and casually trotted down the aisle (at left, above) and out the front door, jogging back with a smile to his seat soon thereafter.

Meanwhile the minister addressed his congregation, mainly discussing what he saw as the extremely decrepit condition of the present church building and calling for its replacement with a new, more “modern” building. He held up as an impressive example the huge, concrete-block church currently being built in the town of Owerri (in Igboland, well to the north). We had seen this structure ourselves, and it was a very massive building indeed, but extremely ungainly in comparison to the present place of worship in our eyes. Beauty was clearly in the eyes of the beholder. (Today, the Liverpool prefab is indeed long gone, replaced by a concrete-block structure. [pc B.F.])

Later that day, we saw ritual culminations for two newly-marriage-eligible young women, being brought out from the seclusion which European Colonial observers had called the “Fattening House”, a misleadingly negative stereotype of an educational process where girls were separated from males and secluded among knowledgable female elders, trained in arts of cooking and household management, beautification, sexual pleasure, child bearing, and other marriage skills, and were now ready to re-appear in public view. We understand that the two young women photographed below as they were emerging from the process (they are called /Iriabo/ by Opobo people) come from the Fubara compound, historically composed of seven Opobo canoe houses. The women who were escorting them come from two different canoe houses in the Fubara compound. [pc B.F.]

The dress of these young women was, of course, set to the richest level of opulence available to their families. Each woman was then paraded out into public grounds by a group of her House members [the buildings here are part of the Fubara Compound] [pc B.F.]:

This group led their maiden out into public space where an array of old Portuguese cannons proclaimed the locus of civic power:

That is, the overlooking statue of King JaJa, raised up and dedicated under British Colonial adminstration aegis, praising the King as a great early leader:

We posed below-statue after the procession departed. While the Colonial-era statue pediment presented a much-sanitized version of the King’s relationship with the British,

the red sign to the right above, raised up along with Nigeria’s 1960 Independence, reads differently:

Historic Monument

Erected to the Memory of

His Late Majesty

King Jaja of Opobo, Nigeria WCA

1821-1891

Grandfather of

His Highness the Amanyanabo of Opobo

Chief The Hon. Douglas Jaja.

King Jaja Was a Great Nationalist, Soldier

And Explorer. His History is Interwoven with the

Early Growth of Trade and Politics

And With the Founding of Opobo Town

In 1870.

He Was the First African Ruler to Oppose British

Imperialism in West Africa. Defending the course

Of the Independence of His Country, He Was

Kidnapped by British Imperialists in

And Died in harness in 1891 in Teneriffe.

Erected to the Memory of

Jaja, King of Opobo

Born 1821 Died 1891

Early afternoon, preceding the city’s annual contest among the “dance troupes”, men associated with various teams carrying Juju objects could be seen walking along its streets. (The house here is the outside of Sam Annie Pepple house also part of the greater Pepple compound (see further below) [p.c.B.f.].

Opobo December Solstice Visit 1961

By Leonard Plotnicov, Richard Henderson, and Helen Kreider Henderson

(For sources used and contact information, see the bottom of the page.)

[Note: Click on each image to enlarge it!]

During 1961, Leonard Plotnicov, Richard Henderson, and Helen Kreider Henderson were advanced graduate students in Anthropology from the University of California (Berkeley) working in Nigeria, Leonard in the Northern Nigerian town of Jos and the Hendersons in Onitsha in the southeastern part of the country. Leonard was invited by one of his friends in Jos, an Opobo man named Samuel Bel-Gam, to visit Opobo town to witness New Year festivities there, and Leonard arranged to have the Hendersons also join him there as guests. Opobo people, natives of a community of Ijaw-speaking people who had lived prior to British Colonial times on the southern coast of the Niger Delta, expressed great pride in their native traditions and enjoyed displaying annual festivities that celebrated their glorious past.

So the three of us mobilized our two-car caravan in Onitsha and drove to the town of Bori (east of Pt. Harcourt along the creeks of the Niger Delta), where a ferry would carry us across the Imo River to Opobo. The map below, adapted from G.I. Jones 1963 (see Sources), provides the 19th-century historical basis for the location we sought: Opobo Town is shown here near the mouth of the Imo River at bottom right-center on this map.

As historian Kenneth Dike has shown (see Sources), this entire Delta region was little inhabited before European traders came to the coast in the early 1500s (the soil is very poor for farming), but by the 1830s it had become the greatest single trading area in West Africa, dominated for several centuries by the Ijaw Kingdom of Bonny (bottom center on the Jones map above). While early trade was mainly in slaves, during the 19th century palm oil became the dominant export. Prior to the late 1860s, the people of Opobo lived in and were members of the Bonny Kingdom, so our story must start there.

Bonny’s power base was a military organization in which the king and his council of chiefs were each independent traders, operating a navy of cannon-bearing war canoes, each chief supplying at least one armed canoe with crew. Some of these canoes were large enough to carry more than a hundred musket-armed warriors, and during the early 19th century this team of war canoes both gained a monopoly over products of the interior and was able to dictate terms of trade with the European merchants visiting the coast.

In the late 1860s, dispute among Bonny’s ruling families brought civil war, and one faction, led by a military, political, and economic genius named JaJa, abandoned that town, having identified a militarily and economically strategic position at the mouth of the Imo River, and established a center there which became the trading state of Opobo. So successful was JaJa’s leadership that the Opobo settlers quickly replaced Bonny in controlling and expanding interior oil markets (the Imo River being the main corridor inland), and in 1873 they obtained a treaty with England stating that English merchants trading with Opobo could only do so at the port of Opobo Town, and giving JaJa the right to intercept and fine them if they tried to bypass him and enter the interior.

But very soon, expanding European commercial ambitions brought intense conflict with JaJa, and in 1887 the British seized and imprisoned him in Teneriffe (Canary Islands), where he died in 1891. Opobo traders adapted well to their changed situations for a time, but when the world economic depression struck in the 1930s they were financially ruined, and most Opobo people had to emigrate to other parts of Nigeria for economic opportunities. Having taken advantage of their earlier contacts with Europeans, they had pioneered in western education (a Christian school opened in Opobo in 1874), acquired professional skills very early, then settled in other parts of Nigeria as strangers, becoming eventually leading members of the new Nigerian elite, but (as nationalism and interethnic competition erupted in the 1950s) they occupied increasingly uncertain positions in what then became independent Nigeria. This was their situation in 1961 when we visited Opobo.

When Leonard discussed their situation with Opobo people living and working in the Northern Nigerian tin-mining center at Jos, he found them intensely concerned with the preservation of Ijaw culture, and dedicated to the goal of reviving their home town, which for most of the year was now practically a “ghost town”, with a care-taker population ranging somewhere around 300 people. They were especially concerned that their children learn to speak Ijaw as opposed to English, and to re-experience cultural features of times past, including wearing native styles of dress and performing the roles of canoe-team warriors.

Below, Leonard (at right wearing shorts) and his friend Samuel Bel-Gam (wearing the pink dress-shirt) arranged our ferry transportation from the creek-side pier at Bori.

Bori pier still stands today near the head of a sinuous creek that feeds into the Imo River. In 1961 the ferry departing from the end of the mainland road docked at this site, negotiating this creek before entering the open waters of the Imo River estuary. As in 1961, today road access is limited to the eastern side of the river, to the location labeled below “Industrial” Opobo, a site now containing an aluminum smelter complex named after the Ibibio town to the east. (Today this is part of the Ibibio-dominated Akwa Ibom State.) The Opobo we were visiting was the original community, located on the west bank of the river further south and marked by a blue square on this satellite map below. Today this is part of Nigeria’s Rivers State, while the land across the river to the east is in Akwa Ibom State. (Thanks to Google Earth and the other companies indicated for this 2008 image.) Other current images indicate an oil field now located at the mouth of Imo River at map bottom.

In 1961, what we label here “Industrial” Opobo was called by Opobo people “Egwanga Opobo”, and was the main site of market trade (including palm oil), district administration, and boat construction. Many Opobo people lived and worked there, along with Igbo and Ibibio people. [pc B.F., see Sources. According to this source (Ms. Fubara), “The name Egwanga is a corruption of the old Ibani (Ijaw) language. The original term was Igwuanga which means “those hillsides”. You see from Opobo Town’s point everything is more elevated. As one approaches Egwanga from Opobo Town, one sees the red clay hill rising from the waterside, at least that is what I saw as a child.”]

Below, a view of boats on the creek from near the ferry pier. Helen stood waiting at lower right.

Below left, another view of canoe travelers from pier side; below right, a view from the ferry as we embarked.

As the ferry was negotiating the creek, one of the Opobo War-Canoe teams came driving by:

This dugout canoe was a contemporary version of a pre-colonial canoe, which was (in the words of G.I. Jones, describing the form during the 19th century) “a large dug-out… armed with cannon fore and aft which were lashed to the thwarts and it occasionally carried another on a swivel amidships. The fifty or more paddlers now carried muskets….” (Sources, p. 55) Contemporary teams like the one shown here were unarmed (and recruited by different criteria than in former times) but attempting to operate according to Canoe House traditions of performance. The banner on this canoe reads “Ofo na ogu”, meaning (in Igbo) some ritual powers/protections. [p.c.B.F.]

We then saw Opobo Town at a distance from across Imo River:

As we approached, various multi-story buildings became visible. Most of these large, iron-roofed structures were built during 19th-century boom times of the city. And most were, for most of the year in 1961, largely unoccupied.

On closer view, one could see that some buildings were of more recent construction, as the pair at right, below (belonging to the Siminialayi family) [pc B.F.].

The most striking building in Opobo town was King JaJa’s palace, below, which he had ordered prefabricated in England. It was now entirely unoccupied. JaJa’s compound, its central courtyard and some of its encompassing buildings shown below, was Opobo’s largest, while a number of smaller compounds ranged around it repeated this pattern at smaller scales. These were physical reflections of social groups making up traditional Opobo society, called Canoe Houses.

During the 19th century, a Canoe House was a dynamic organization, composed of a number of households, each comprising a man, his wife or wives, his children, servants, slaves and other dependants attached to him. A group of these composite households formed a Canoe House when its leader, having spawned or purchased enough dependants capable of manning a war canoe and mobilized enough wealth to engage in necessary militant activities, was recognized by other chiefs and the king as having “filled his war canoe”, and became a chief in his own right.

The terminology of “house” and “compound” is likely to be confusing to outsiders. According to [pc B.F.], Ms. Fubara, “The way I would describe the terms ‘compound’ and ‘house’ as I have been using them, would allude to the Ijaw erms of ‘polo’ and ‘wari’ , where ‘polo’ is quite literally a compound of different ‘wari’s. ‘Wari’ also means individual houses, but depending on the context, it also means a household or homestead if you will, for a particular clan. So the polo/compound is presided over by a main chief, and the waris/houses by fellow chiefs who may be considered as secondary chieftaincies. These houses are most likely war canoe houses in which case the chiefs were prosperous enough to outfit and man war canoes.”

While JaJa’s compound was the largest, the town was carved into a number of them. Viewed across rooftops, you can see several basically rectangular outlines below. The flag rising over rooftops at left-center represents one Canoe House.

The Canoe House as settlement consisted of a walled compound entered through a gate, shown below. The main House within it stands here at right, raised off the ground on pillars, with living quarters mainly on the upper floor. The house inside is the Omubo Pepple house, within the larger Pepple compound. In former times every compound of this kind had a protective gate. [p.c.B.F.]

This one below shows the basic pattern most clearly, with living quarters above and storage level below, the whole presenting a fortified structure to outsiders. This house belonged to Chief Oko Jaja, a subordinate chief to King Jaja [p.c.B.F.].

The tomb statue in this compound below was dedicated to Warribe Uranta, born in Bonny in 1859.

this smaller compound below was dominated by a single figure. (Note the style of lamp poles bracketing the figure. Poles of this type were scattered widely through the town. None we saw was currently lit.)

This one bore the label,

This Monument

And Statue

Is erected in the memory of

The late

SUNJU PETERSIDE

Of Opobo

Who was born at Ayamma

On the

Sixth Day of September 1859

And died on the

21st Day of December 1925

This compound below had several memorial structures, and also shrines. This was the main House of Ogolo compound [p.c.B.F.]. Concrete blocks lined along the ground were presumably for use in building construction at left.

Mr. Bel-Gam (part of the Cookey House) and his family, our hosts, housed us very comfortably in their own home, below, the fine brick house in the background, and immediately found native dress for us and showed us how to clothe ourselves in appropriate fashion. Women of the household took particular care getting Helen’s clothing right. This house belonged to Mr. Eustace Jaja, seen here standing just behind Helen. [pc B.F.] He and the others shown here treated us with great hospitality.

We then went off to church, along the town’s neatly curving walkways.

St. Paul’s Church, part of Niger Delta Pastorate of the Church Missionary Society (CMS), was prefabricated of iron and wood by an English firm in Liverpool during 1906, reassembled in Opobo in 1907. It is now quite venerable, not much to look at outside (but see further below!):

Our party met the Amanyanabo (King) of Opobo in front of the church prior to service. Here you see Helen wearing the epitome of proper native dress according to our hosts’ standards. Of all the people we saw in Opobo during our visit (with the sole exception of the man standing behind, in the doorway), the Amanyanabo was the only adult person who did not wear the native attire, dressing instead in impeccably formal English style. Mr. Jaja stands at the Amanyanabo’s right. [Mr. Ngozi Fubara stands just behind Helen and Leonard, and Mr. Denne Finebone stands at far right in the church doorway. [pc B.F.]]

Below, Dick and Leonard wore close approximations to correct native dress, in particular imported light-flannel dress shirts with extremely long tails and colorful wrappers below. The man at left is not quite correct in that regard, but he is closer to it than our host, who dressed in a lighter-textured, short-sleeved shirt.

Entering church for service, we were wholly unprepared for the soaring and elegant beauty of its interior (note: dust marks apparent on pillars etc. are products of poor photographic slide storage over some 47 years, not part of the building):

Seating arrangements in church placed women at left and men at right. Seats allocated to chiefs are seen most clearly in the image above, where the man in white at left rear is momentarily sitting. Our party was allocated places there, and no chiefs joined us on this particular day. The Amanyanabo sat in a separate chair in the aisle just below the pulpit. (In the image below, the woman in the green-chevroned wrapper and white blouse is Esther Fubara [pc B.F.].

As the minister began his address to the congregation from the pulpit, the Amanyanabo began addressing us in an even louder voice, asking us how our visit was going, what we had been doing since our arrival, etc. Startled by this unexpected, competing side commentary, we answered in very brief terms. Shortly thereafter, he arose and casually trotted down the aisle (at left, above) and out the front door, jogging back with a smile to his seat soon thereafter.

Meanwhile the minister addressed his congregation, mainly discussing what he saw as the extremely decrepit condition of the present church building and calling for its replacement with a new, more “modern” building. He held up as an impressive example the huge, concrete-block church currently being built in the town of Owerri (in Igboland, well to the north). We had seen this structure ourselves, and it was a very massive building indeed, but extremely ungainly in comparison to the present place of worship in our eyes. Beauty was clearly in the eyes of the beholder. (Today, the Liverpool prefab is indeed long gone, replaced by a concrete-block structure. [pc B.F.])

Later that day, we saw ritual culminations for two newly-marriage-eligible young women, being brought out from the seclusion which European Colonial observers had called the “Fattening House”, a misleadingly negative stereotype of an educational process where girls were separated from males and secluded among knowledgable female elders, trained in arts of cooking and household management, beautification, sexual pleasure, child bearing, and other marriage skills, and were now ready to re-appear in public view. We understand that the two young women photographed below as they were emerging from the process (they are called /Iriabo/ by Opobo people) come from the Fubara compound, historically composed of seven Opobo canoe houses. The women who were escorting them come from two different canoe houses in the Fubara compound. [pc B.F.]

The dress of these young women was, of course, set to the richest level of opulence available to their families. Each woman was then paraded out into public grounds by a group of her House members [the buildings here are part of the Fubara Compound] [pc B.F.]:

This group led their maiden out into public space where an array of old Portuguese cannons proclaimed the locus of civic power:

That is, the overlooking statue of King JaJa, raised up and dedicated under British Colonial adminstration aegis, praising the King as a great early leader:

We posed below-statue after the procession departed. While the Colonial-era statue pediment presented a much-sanitized version of the King’s relationship with the British,

the red sign to the right above, raised up along with Nigeria’s 1960 Independence, reads differently:

Historic Monument

Erected to the Memory of

His Late Majesty

King Jaja of Opobo, Nigeria WCA

1821-1891

Grandfather of

His Highness the Amanyanabo of Opobo

Chief The Hon. Douglas Jaja.

King Jaja Was a Great Nationalist, Soldier

And Explorer. His History is Interwoven with the

Early Growth of Trade and Politics

And With the Founding of Opobo Town

In 1870.

He Was the First African Ruler to Oppose British

Imperialism in West Africa. Defending the course

Of the Independence of His Country, He Was

Kidnapped by British Imperialists in

And Died in harness in 1891 in Teneriffe.

Erected to the Memory of

Jaja, King of Opobo

Born 1821 Died 1891

Early afternoon, preceding the city’s annual contest among the “dance troupes”, men associated with various teams carrying Juju objects could be seen walking along its streets. (The house here is the outside of Sam Annie Pepple house also part of the greater Pepple compound (see further below) [p.c.B.f.].

As historian Kenneth Dike has shown (see Sources), this entire Delta region was little inhabited before European traders came to the coast in the early 1500s (the soil is very poor for farming), but by the 1830s it had become the greatest single trading area in West Africa, dominated for several centuries by the Ijaw Kingdom of Bonny (bottom center on the Jones map above). While early trade was mainly in slaves, during the 19th century palm oil became the dominant export. Prior to the late 1860s, the people of Opobo lived in and were members of the Bonny Kingdom, so our story must start there.

Bonny’s power base was a military organization in which the king and his council of chiefs were each independent traders, operating a navy of cannon-bearing war canoes, each chief supplying at least one armed canoe with crew. Some of these canoes were large enough to carry more than a hundred musket-armed warriors, and during the early 19th century this team of war canoes both gained a monopoly over products of the interior and was able to dictate terms of trade with the European merchants visiting the coast.

In the late 1860s, dispute among Bonny’s ruling families brought civil war, and one faction, led by a military, political, and economic genius named JaJa, abandoned that town, having identified a militarily and economically strategic position at the mouth of the Imo River, and established a center there which became the trading state of Opobo. So successful was JaJa’s leadership that the Opobo settlers quickly replaced Bonny in controlling and expanding interior oil markets (the Imo River being the main corridor inland), and in 1873 they obtained a treaty with England stating that English merchants trading with Opobo could only do so at the port of Opobo Town, and giving JaJa the right to intercept and fine them if they tried to bypass him and enter the interior.

But very soon, expanding European commercial ambitions brought intense conflict with JaJa, and in 1887 the British seized and imprisoned him in Teneriffe (Canary Islands), where he died in 1891. Opobo traders adapted well to their changed situations for a time, but when the world economic depression struck in the 1930s they were financially ruined, and most Opobo people had to emigrate to other parts of Nigeria for economic opportunities. Having taken advantage of their earlier contacts with Europeans, they had pioneered in western education (a Christian school opened in Opobo in 1874), acquired professional skills very early, then settled in other parts of Nigeria as strangers, becoming eventually leading members of the new Nigerian elite, but (as nationalism and interethnic competition erupted in the 1950s) they occupied increasingly uncertain positions in what then became independent Nigeria. This was their situation in 1961 when we visited Opobo.

When Leonard discussed their situation with Opobo people living and working in the Northern Nigerian tin-mining center at Jos, he found them intensely concerned with the preservation of Ijaw culture, and dedicated to the goal of reviving their home town, which for most of the year was now practically a “ghost town”, with a care-taker population ranging somewhere around 300 people. They were especially concerned that their children learn to speak Ijaw as opposed to English, and to re-experience cultural features of times past, including wearing native styles of dress and performing the roles of canoe-team warriors.

Below, Leonard (at right wearing shorts) and his friend Samuel Bel-Gam (wearing the pink dress-shirt) arranged our ferry transportation from the creek-side pier at Bori.

Bori pier still stands today near the head of a sinuous creek that feeds into the Imo River. In 1961 the ferry departing from the end of the mainland road docked at this site, negotiating this creek before entering the open waters of the Imo River estuary. As in 1961, today road access is limited to the eastern side of the river, to the location labeled below “Industrial” Opobo, a site now containing an aluminum smelter complex named after the Ibibio town to the east. (Today this is part of the Ibibio-dominated Akwa Ibom State.) The Opobo we were visiting was the original community, located on the west bank of the river further south and marked by a blue square on this satellite map below. Today this is part of Nigeria’s Rivers State, while the land across the river to the east is in Akwa Ibom State. (Thanks to Google Earth and the other companies indicated for this 2008 image.) Other current images indicate an oil field now located at the mouth of Imo River at map bottom.

In 1961, what we label here “Industrial” Opobo was called by Opobo people “Egwanga Opobo”, and was the main site of market trade (including palm oil), district administration, and boat construction. Many Opobo people lived and worked there, along with Igbo and Ibibio people. [pc B.F., see Sources. According to this source (Ms. Fubara), “The name Egwanga is a corruption of the old Ibani (Ijaw) language. The original term was Igwuanga which means “those hillsides”. You see from Opobo Town’s point everything is more elevated. As one approaches Egwanga from Opobo Town, one sees the red clay hill rising from the waterside, at least that is what I saw as a child.”]

Below, a view of boats on the creek from near the ferry pier. Helen stood waiting at lower right.

Below left, another view of canoe travelers from pier side; below right, a view from the ferry as we embarked.

As the ferry was negotiating the creek, one of the Opobo War-Canoe teams came driving by:

This dugout canoe was a contemporary version of a pre-colonial canoe, which was (in the words of G.I. Jones, describing the form during the 19th century) “a large dug-out… armed with cannon fore and aft which were lashed to the thwarts and it occasionally carried another on a swivel amidships. The fifty or more paddlers now carried muskets….” (Sources, p. 55) Contemporary teams like the one shown here were unarmed (and recruited by different criteria than in former times) but attempting to operate according to Canoe House traditions of performance. The banner on this canoe reads “Ofo na ogu”, meaning (in Igbo) some ritual powers/protections. [p.c.B.F.]

We then saw Opobo Town at a distance from across Imo River:

As we approached, various multi-story buildings became visible. Most of these large, iron-roofed structures were built during 19th-century boom times of the city. And most were, for most of the year in 1961, largely unoccupied.

On closer view, one could see that some buildings were of more recent construction, as the pair at right, below (belonging to the Siminialayi family) [pc B.F.].

The most striking building in Opobo town was King JaJa’s palace, below, which he had ordered prefabricated in England. It was now entirely unoccupied. JaJa’s compound, its central courtyard and some of its encompassing buildings shown below, was Opobo’s largest, while a number of smaller compounds ranged around it repeated this pattern at smaller scales. These were physical reflections of social groups making up traditional Opobo society, called Canoe Houses.

During the 19th century, a Canoe House was a dynamic organization, composed of a number of households, each comprising a man, his wife or wives, his children, servants, slaves and other dependants attached to him. A group of these composite households formed a Canoe House when its leader, having spawned or purchased enough dependants capable of manning a war canoe and mobilized enough wealth to engage in necessary militant activities, was recognized by other chiefs and the king as having “filled his war canoe”, and became a chief in his own right.

The terminology of “house” and “compound” is likely to be confusing to outsiders. According to [pc B.F.], Ms. Fubara, “The way I would describe the terms ‘compound’ and ‘house’ as I have been using them, would allude to the Ijaw erms of ‘polo’ and ‘wari’ , where ‘polo’ is quite literally a compound of different ‘wari’s. ‘Wari’ also means individual houses, but depending on the context, it also means a household or homestead if you will, for a particular clan. So the polo/compound is presided over by a main chief, and the waris/houses by fellow chiefs who may be considered as secondary chieftaincies. These houses are most likely war canoe houses in which case the chiefs were prosperous enough to outfit and man war canoes.”

While JaJa’s compound was the largest, the town was carved into a number of them. Viewed across rooftops, you can see several basically rectangular outlines below. The flag rising over rooftops at left-center represents one Canoe House.

The Canoe House as settlement consisted of a walled compound entered through a gate, shown below. The main House within it stands here at right, raised off the ground on pillars, with living quarters mainly on the upper floor. The house inside is the Omubo Pepple house, within the larger Pepple compound. In former times every compound of this kind had a protective gate. [p.c.B.F.]

This one below shows the basic pattern most clearly, with living quarters above and storage level below, the whole presenting a fortified structure to outsiders. This house belonged to Chief Oko Jaja, a subordinate chief to King Jaja [p.c.B.F.].