We arrive in Onitsha near the end of September, 1960, riding on the great vehicular ferry then running across the Niger between Asaba and Onitsha. We stay overnight in the government-run Catering Rest Houses (arranged fopr us by our contact, Dr. Lawrendce Uwechia. (Helen enjoys a cup of tea in front of our casita.)

The next day, Dr. Uwechia arranged for assistance in finding us housing. We had specified our desire to live in “The Inland Town”, which considerably constrained us. Our first visit to a potential residence was near the northeastern edge of the Inland Town (near Awka Road), located in Umu-Eze-Aroli Village, and this was a great shock to us. (regrettably, I took no pictures of this place, so eager was I to depart from it.)

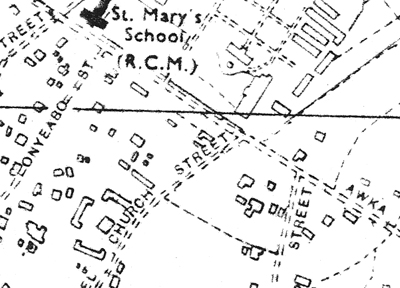

This place a is visible on the map at left, directly south of St. Mary’s School along Emmanuel Church Street. What you see is a “square” marked off by three large, U-shaped buildings facing a center. On the ground these buildings were very massive, and I later learned that the complex was indeed a “palace” built by Simon Egbunike in the 1930s, anticipating that he would become King and occupy this spot.

(See Chapter Five, “Sought…”, “Umu-Eze-Aroli…, no. 5, “The 1931-35 Interregnum”. for more details regarding the history of Mar. Egbnuike).

At the time I retreated from this sight as fast as I could, not pausing to wonder why we had been shown something as monstrous as this giant bed of stair-stepped concrete. Perhaps this was an informal guess regarding our available wealth — there were definitely ample quarters for large numbers of servants should we have been wanting them.

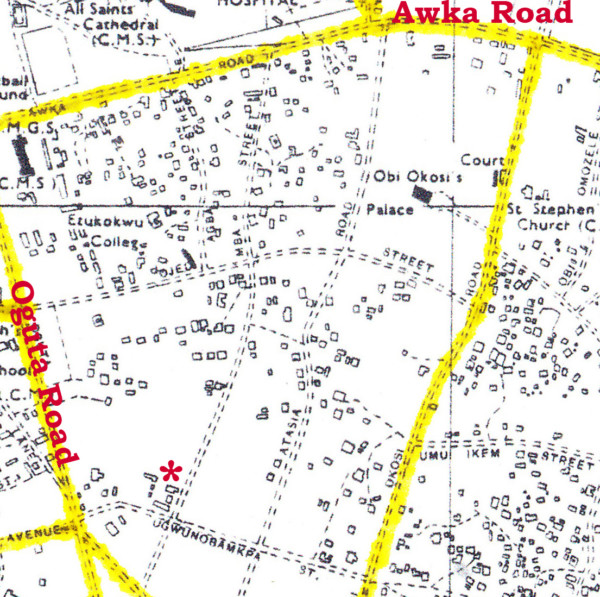

The second prospective rental was at the opposite end of the Inland Town,

This house was located on the far southwestern edge of the Inland Town, as shown by the red star along Mba Road near the east-west Ugwunaobamkpa road that leads further in. This was the southern edge of the macro-village of Umu-Dei (though this house was owned by an Isiokwe men (a fortunate connection for us, as we shall see).

This rental was the “upstairs” portion of a two-story building, with walls running round the perimeter (topped with broken glass to deter thieves). the entryway is at far left (obscured by the palm fronds), an open stairway leads up to the front balcony where Helen stands in this image. The living room was behind her; the room at right became an office. Behind that was a fully operational modern bathroom , behind that a bedroom, and at left behind the living room was the kitchen with a wood-burning stove. The grounds were gated and we could park our tiny vehicle, “motu machis”, inside.

The homeowners lived downstairs, the husband/father Albert Erokwu (and Ozo-titled man from Isiokwe village, is wife Merci,,a native of Obikporo Village, and their four children (two older girls, two younger boys). The rent was 12 pounds six shillings per month. We lept at the chance.

When we arrived in 1960, the Inland Town boundary was still marked to the west by the Oguta Road running southward from the Roundabout, and to the north (though more roughly) by the Awka Road running east from the roundabout (dividing the Inland Town from the European Quarters still housing mostly Government establishments and officials). Behind this perimeter, the indigenes actively defended their “High-Onitsha” (enu-onicha) space, using such mechanisms as forbidding land transfers to outsiders and mobilizing the Incarnate Ghosts (mmanwu) Masquerade organization to intimidate interlopers, and although the boundaries had become permeable (we ourselves lived within a peripheral zone of the Inland Town — we had Onitsha villagers next door to our north and immigrant ndi-Igbo neighbors next door to our south), those living inside this space were either “Ndi-Onicha” or they were transients.

While by 1960 there were many more European style houses and corrugated tin roofs dotting the Inland Town than Leith Ross described for the 1930s, the contrasts still obtained between “noise vs. silence,” — but, more accurately, in the kinds of sounds one might hear: between the Waterside’s omnipresent building construction materials/activities, throngs of traders (mostly men), horn honking, madcap driving motor traffic, and the Inland Town’s silent gardens, houses of traditional design, extensive patches of high forest, small groups of women sitting in casual village markets beneath great trees, occasional orchestras accompanying brightly-costumed social groups dancing by, often singing in aurally enriched social formations (mostly women). Because of very frequent funeral activities, sounds of drumming ( and sometimes, of mourners calling out “Ewo, Ewo” [“woe”]) filled the air.

Helen and I very much preferred the aesthetic ambience of the Inland Town, but our Westernized elite Nigerian contacts (whether Onitsha or non Onitsha) mostly sniffed at this in response, describing the Inland Town as “dirty” (a reference to its mostly unpaved roads and the prevalence of vegetation, including stretches of “bush”), and they preferred the Waterside (which we found too noisy, over crowded, florally and faunally barren, and persistently stinking faintly with its very numerous open sewers and ever smouldering, almost centrally located garbage dump).

The Inland Town resounded with frequent but sufficiently distant drum music by day and (often) into the night, and (as ethnographically entranced semi- insiders) we enjoyed the periodic visual, aural, and social emergence of unfathomable mystical forces from nearby patches of forested bush. On more than one night, we were actually visited by the mysterious Ayakka and were embraced beneath its swirling roar. For some visual examples, See the riches celebrated in Chapter 3, in the page “Enu-Onicha 1960-62,” section 4: “Boundaries protected by the Incarnate Dead.”)

What we did make clear by this residential choice, however, was that we did not intend to participate much in the “local elite” life centering around “European-style” activities in the Waterside. This definitely made us peripheral to that world, which was in any case necessary for our plans of work: our Ford Foundation Grant did not encompass efforts to engage seriously in the local High Society, which was high enough and intensive enough that our residence in Onitsha would have become drastically foreshortened due to limits of funds, and of course we would have been pulled away from the historical dimensions that quickly became our primary focus. 1

We did visit the Waterside regularly, conducted research inside the Main Market and several local schools, and Ifekandu Umunna and I conducted a photographic & descriptive survey of much of the Waterside along the two main streets. [See, in this chapter, the page on “Otu (Waterside)]. But it is fair to say that our work was strongly skewed into the Inland Town and its occupants relative to those outside it..

- A book describing “Nigerian elites” was published in 1960 while we were still in Onitsha. See Smythe & Smythe 1960 in Chapter 9, Bibliography. [↩]