Above: Ime-Obi, The Palace of the Obi of Onitsha. Note the protective “mediicine” (oda), a bundle suspended over the arch entryway, which protects inhabitants within from dangers that may be brought in from without.

At left, the Palace “looks out”over its Public Square (ilo), which contains a second building of spiritual importance (middle right). The entryway (middle left) leads into a major meeting space where, every year traditionally, the King emerges from seclusion to dance among his chiefs in the presence of the public..

Note: On this page we provide the briefest of visual and written introductions to this “heart” of the”+two-hearted” city. A much more detailed account appears in Chapter Two, under an almost identical heading. Here we merely open the doors so speak.

At left, the District Officer’s map from the early 1930s draws the contrast between Otu and Enu by simply assigning numbers to each of the distinctive villages of the latter. Unlike the very recent occupation of most of the Waterside, these primarily residential unitsassociated with these numbers have ancient history, and their various residents can trace their arrivals here over some centurie (and in some cases from various “other places”.

When, in 1960-62, we depart from the streets near the Main Market and enter these Heights with their intensified vegetation, we encounter places that contrast sharply with the Waterside (Otu): as you see below, we suddenly encounter bodies of forest, garden spaces, scenes ordinarily much quieter than the Otu;, mostly-unpaved streets dotted with small buildings some painted white to indicate specific loci of spirituality, and others of similarly “non-functional” character:

Villages are ordered around shrines

At left, both of these buildings are shrines, the white one dedicated to Ojedi, a famous woman associated with UmuDei Village, the red one dedicated to Omumu, a childbirth-supporting Spirit venerated by the people of Ogbe-Onira (a sub-village within Umudei). Every shrine is associated with one of the Villages (Ogbe-) of the Inland Town.

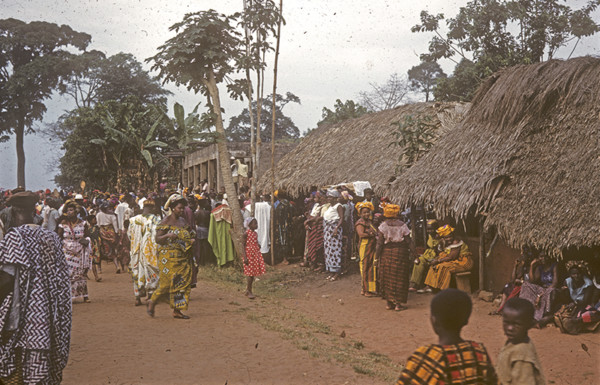

Sociality emphasizes dramatic dress styles

And Below, dress styles and behaviors in the Inland Town tend to contrast sharply with those typical of people whose current activities focus in Otu. In the (quite frequent) formal occasions, much more wealth and “style” is displayed in clothing worn, styles are more diverse, and behavioral patterns tend toward the collectively dramatic: in this massive ritual gathering seen below, the feathered crowns worn by these Onitsha titled chiefs (ndichie) are highly potent symbols conveying many layers of sociocultural meaning. And observe the dress of men toward to lower left: diverse forms of formal dress are in display.

And for major ritual events, Onitsha People accommodate themselves in openly non-“modernr” decorated halls, carrying (and wearing) ritual objects whose meanings both testify to holders’ wealth and affirm that they represent more esoteric symbolic values: at left, a woman representing a senior female organization of the wider community is escorted into the Palace Courtyard by two spiritually-purified men (holders of the sanctified ozo title). Symbols indicated by white colors are prominent; the greatly prized ivory (in horns held by the men and in the leg-ornaments worn by the woman) are direct indicators of spiritual (and social) power.

The Spiritual Qualities of People are descent-divided, stratified and age-graded

Several layers of Spiritual Quality exist, capped by the Onitsha King (Obi), as he appeared at his Emergence from his ordinary seclusion inside it in 19601. While he stands at the apex, his social powers, replicated and transformed, appear at several levels in this society.

On that occasion, he was forrmally saluted by his array of Chiefs (Ndichie)., each of which is selected from a particular Onitsha Village. Different levels of Village tend to be represented by different levels of chieftaincy title.2

At left, an “Age-grade” (Ogbo) — Inland-Town-wide organization grouping together all persons within a three-year birth period that cross-cuts all village divisions. These organizations actively participate in a variety of community events, and one of them is said to “Watch Over the Land”.

Within villages, residential houses take peculiar forms. Some we might class as “modern”, others definitely follow a different standard. The older versions were built according to a very specific set of household standards, and some of the newer ones also follow this in their interior designs. Socially the most important houses are those defininging a patrilineal descent-group “church”, what I have called an “Ancestral House”.

Villages (and sub-villages) are spatially marked by physically obvious ritual centers, called ilo, which provide ritual foci for the villagers, for example hereat left a shrine (the omumu ‘birth shrine”) dedicated to ensuring the fertility of village wives , a rounded mound of earth into which kitchen pots have been molded and which receives regular acts of social recognition. While this particular example is a very small Ilo, it contains crucial ceremonial aspects of the form, including banana trees (at right), planted there to attract children who have died to reincarnate in this village.

And in each village, households are organized around the focus of a patriarch who regularly sits on his ‘throne” (ukpo) and supervises the worship of various “idols” as part of his task to ensure the welfare of his subjects. All members of this group are subject to the powers of these objects.

These objects take a startling variety of forms:, each of which has its own distinctive function — for exmple, note the set of objects (lumped together as ndi-mmuo, “ghosts”) that are covered with chicken feathers: each set of feathers records a distinctive act of blessing given to these “ghosts”.

Note the all-white, boat-like-shaped object at lower right in this image. This is an object of central social significance for di-Onicha: it is a sign that this particular priest is a holder of the Ozo title, which means in turn that he has attained a permanent level of spiritual purity that places him above that of ordinary men.

Ozo Title: The Social/Spiritual Transformer (for men)

And — particularly at the edges of the Inland Town — strange figures that I eventually called “Incarnate Dead” (because although they take obviously visible form, Onitsha people insist on calling them “ghosts” (ndi-mmuo), and they stalk through the streets, “untouchables”, yet accorded the highest degrees

of respect. they actively “police” the social order where they go.

Thus the activities of Ndi-Onicha within and between the Villages of the Inland Town are many and diverse. But it must be said that a great number of activities focus upon what may best be described as “both mourning and celebrating death.” To give one specific illustration here:

During the seasons of funerals (Ikwa-ozu, “Lamentation”)the Inland Town rings with the sounds of bells, gongs, and drums, and social groups of various sizes and modes of organization throng through the streets in colorful arrays. At left, a n;umber of different social groups congregate at the Death house, where the patrilineage Daughters (umu-ada) strand by to protect a coffin-like symbol of the deceased. This is but one small example of a variety of distinctive kinds of ritual that engage large proportions of the Inland Town during a year.

Part of the reason for this great elaboration of customs revolving around the death of individuals is that such a high proportion of the Inland Town are elderly — a vastly higher percentage than live in the Waterside. While numerous children live in Enu-Onicha, and when they die they have funerals, enu-Onicha has a much higher proportion of very elderly people, hence much more frequent funerals3.

The average age of Waterside inhabitants is far lower, and beyond this, when individuals living in Otu die, their corpses are most likely transferred immediately to their rural homelands. Consequently, the Waterside is substantially less occupied with mourning (and when Ndi-Onicha who live there die, their corpses are mostly conveyed into Enu Shrines-&-Ilo-Ikemefuna 1962 for the appropriate ritual treatment).

Summary Overview:

This brief survey should provide a strong sense of how different Inland Town (enu-Onicha) social life is from the Waterside (Otu.) In terms of meaningful heights and depths, these people of “High Onitsha” tend to reject any claims to social equality with theirimmigrant Waterside neighbors , most of whom have come to Onitsha from similar uplands to the east (from towns whose people are called (Ndi-Igbo).4 Ndi-Onicha instead affirm their ancient connections with those of the Riverine floodplains (Ndi-Olu), yet they also state that (historically) they “cannot swim”. They also say, “We are the landowners”, claiming to own the lands immediately around them in all directions. Yet they also boast of ancient migrations — that they came from far away, over uplands far to the West across the Niger. Generally speaking, they reject immigrant Ndi-Igbo demands for equality, formally stating on one 1958 proclamation, “They can pack and go!” (back to their homelands).

For their part, the migrant Ndi-Igbo traders and others who live now (most of their time) in the lower elevations of Onitsha he city called Otu, reject any suggestions of their inferiority to Ndi-Onicha, and (this is 1960-62) proudly call themselves “Non-Onitsha Ibos“.

Finally, should we turn more closely to examine the affairs of Ndi-Onicha, we will find that internally, they themselves have highly divided identities: some Ndi-Onitsha villagers claim they can swim at birth, call themselves Ndi-Olu and on occasion sass their fellow Ndi-Onitsha as being “Ndi-Igbo” in contrast to themselves. Others regard various sub-divisions of Enu-Onicha as secretly Ndi-Igbo (though those so-labeled staunchly deny it and may label their accusers as Ndi-Igbo as well. Chinua Achebe’s observation that Onitsha contains “a zone of occult instability” would appear to apply in a number of personal, social, and cultural dimensions.

A Brief Reality Check:

Bear in mind here that so far we are looking at an Onitsha of the past. The city was largely destroyed during the Biafra-Nigeria Civil War of 1967-70, most of its occupants dispersed , and it was described in elegaic terms by one of the most insightful chroniclers of its pre-Civil-War Onitha market literatures, Dr. E.N. Obiechina, who wrote these words shortly after the end of the War5:

“Onitsha market… was totally gutted and its many thousand colorful and adventurous denizens scattered near and far. Onitsha itself… lies battered and in ruins, drained of its vitality.”

“Onitsha was a unique town. It attracted to itself all types of adventurers, self-confident and imaginative people… a town with a highly developed sense of its human consciousness…. Everyone there was acutely aware of his human relevance whether he was rich or poor, trader or artisan, professional or casual labourer….

“Onitsha attracted both the good and the bad, but mainly those young men and women who were running away from the rigours of traditional life and tribal village custom. It held an umbrella of anonymity over their heads and allowed them to give free play to their individualities.”

It drew into its bosom an assortment of peoples from beyond the immediate neighbourhood…. The Hausa ivory trader… Nupe and Igala clothdyer and dealer in bric-a-brac… Ijaw fisherman and canoe-puller… Yoruba petty-trader…Edo produce merchant.. Sierra Leonean professional. Each of these brought his peculiar calling, his peculiar habits and customs and his peculiar psychology to add to the colour and diversity of life in Onitsha, to enrich its general pool of human experience.”

We will briefly examine some of this history in later parts of this work. For now, let it suffice to say that city and market were rebuilt during the 1970s, and Onitsha has grown massively in population since the end of the Nigeria-Biafra war, but to what extent it has recovered its 1960 dynamism so admired by Achebe, Obiechina, and other writers describing those earlier times is problematic. The next chapter will now focus on more detailed views of that late 50s-to-early-1960s, hyper-energetic past.

- The poor quality of this image–(among others at the time — led me to scrap the use of my telephoto attachment t my t Aires camera. [↩]

- Each exalted person here wears headgear reminiscent of “A mighty Tree”. [↩]

- Ojiabu Onyeachonam, shown here, was an octogenarian when he died during our time there in 1961 [↩]

- One opinionated Onitsha man said to me, “We regard them as Beasts!.” [↩]

- Obiechina 1972, pp. 27- 9. [↩]