[Note: Click on any image you may want to enlarge.]

During the weeks of late April through May 1961, while the Royal Clan meetings struggle at evolving a viable organizational focus, members of the Enwezor group find themselves chafing at an enforced period of relative idleness. While they make some efforts to discourage the Umu-EzeChima meetings, their own few Committee meetings are aimed largely at obtaining the support of the Onitsha Prime Minister, Anatogu Onowu. 1 But from their point of view the Onowu appeares to be stalling; on May 20 Aniweta tells me that when the Ndi-Onicha Prime Minister consulted with Nigerian Governor -General Nnamdi Azikiwe (then visiting Onitsha) about the kingship, Zik told him to wait: the time is not yet ripe for making final decisions.

This troubles Aniweta, because it exposes a point of uncertainty felt by Enwezor’s group concerning the Prime Minister’s disposition toward their candidate. The Onowu is a Daughter’s Child (nwa-di-ani) to Ogbeabu, not only Zik’s own village but also that of the late King Okosi II in Okebunabo. An Onitsha public legend asserts that Anatogu, as a condition of completing his Senior Chieftaincy title, was required by Okosi II to swear an oath to support whomever the Okosi family might eventually choose as successor to Okosi II’s throne. Since such an oath is regarded as doubly binding when made by a Daughter’s Son to his Mother’s People, and since Zik is also a member of Okosi II’s major village, there is ample reason for anxiety within Umu-EzeAroli about what the two men may have discussed in their recent meeting. Might they be hatching Ogbeabu- (maybe Okebunabo-) oriented plans?

Okebunabo, the largest major segment of the Royal Clan, is anyway now becoming a more serious source of anxiety for Enwezor’s group, in part because (as the home of the Okosi dynasty) its members are very strongly Roman Catholic in Christian affiliation (thanks partly to the Holy Fathers’ helpful intervention bringing them kingship in 1900), and word is circulating that the devout-Catholic kingship candidate Moses Odita is now touring Okebunabo and offering money to various leaders there in exchange for their support. Since leaders of Okebunabo are, moreover, also very much involved in the Royal Clan Conference (whose activities are visibly gaining momentum), it seems probable they might be swayed to use that involvement to further Odita’s cause in the Conference Special Committee’s current deliberations. Odita is considered an exceptionally serious threat because of his national (and even, modestly, international) reputation as well as his devotion to the RCM.

Obiekwe Aniweta, however, is consistently a man of action and has no intention of leaving all the initiatives to others. On May 25, after he escorted me to a visit with Igwe Enwezor to discuss who are the real “immigrant” groups in the Royal Clan, he excuses himself, saying he must visit an important leader of the OzoTitle Association, to obtain “some anti -Catholic material to use as a political device.”

1. “Religious Politics” in Onitsha Urban: “Otu” Focus

Briefly to foreground this account from the perspective of readers in the 2000’s years or thereabouts, bear in mind that we are here describing a time and context that was prior to the Vatican II Council of the Roman Catholic Church. To quote an eminent Jesuit priest2:

“Before the (Vatican II) council, Catholics were not only forbidden to pray with those of other faiths but also indoctrinated into a disdain or even contempt for them. (This was, of course, a two-way street.)”

………………………………………

We hear the phrase “religious politics” repeatedly in Onitsha from the beginning of our stay in 1960, always with reference to the unstable balance of strength or influence between the Anglican Church Missionary Society (CMS) and the Roman Catholic Mission (RCM). Both missions are prominent, powerful, and thoroughly established, not only in Onitsha but throughout most of Eastern Nigeria. But from the initial entry of the RCM into Onitsha in l885, invading a sphere which had been proselytized by the CMS since l857, the two groups have been locked in a protracted, often bitter struggle for dominance, and this conflict has intensified with the advent of Nigeria’s Independence. 3

While most Nigerian political organizations now officially aim to expunge religious issues from party organization, a very strong concern is rising with 1960 Independence about the relative “balance” in numbers of Protestants and Catholics occupying ministerial and other official positions in the new Eastern Regional government, which is dominated by Nnamdi Azikiwe’s NCNC. While substantially more people identify themselves as Roman Catholics than Protestants in Eastern Nigeria, Protestants are now more strongly represented in key positions of regional Government, and the RCM (which keeps careful account of numerical representation) is dissatisfied with the NCNC’s current pattern of official leadership. The fact that Zik’s loyalties are unambiguously Protestant no doubt intensifies their worries. Azikiwe’s opposition to the expatriate priests of the RCM was evident from his first years as editor of the West African Pilot, where he gave positive coverage almost exclusively to the CMS. 4

From the beginning of our fieldwork we try to avoid being identified with either group (emphasizing to anyone who asks that as anthropologists we are of course students of all religions, though especially interested in the study of non-Christian ones), and we make efforts to associate with adherents of both of the two major Christian types. But it gradually becomes clear to us that for some local people mission affiliation is a primary indicator of social and personal identity, while for most others for at least some social contexts it becomes a highly significant indicator.

To the Irish Roman Catholic priests who at this time fill the church hierarchy in Nigeria, visiting Americans like ourselves, who emphasize our strong support for the new American president (John Kennedy having taken office barely 5 months after our arrival), are welcome guests, and they not only invite us into their quarters but encourage our research. Still, they quickly sense we are not ourselves Catholics. The Anglican churchmen (who remain mostly British expatriates at the top, but have substantially Africanized their middle ranks) seem to assume we are Protestants, though we give them no affirmations of religious affiliation. (I once turned away from then-Bishop Patterson’s slightly extended finger-ring. Not something I had any idea of what to do.) We seek and receive advice from both groups about documents and individuals to consult in our historical research (for example, the works of CMS missionary G.T. Basden) 5.

Among the African population at large, we experience almost no overt discrimination directed towards our religious affiliations (or lack of them), while among Onitsha people considerable delight is expressed that we are anthropologists and therefore people presumably prepared to respect their traditional religion. The experience of positive welcomes from most sides gives us a false sense that we can move more easily among the various religions competing for souls in Onitsha town than will actually prove possible in the long run.

The religious situation in Onitsha is a peculiar one. In my early work find that most traditionalist Inland Town informants who discuss the subject affirm to me that they have been raised during at least part of their careers as Roman Catholics, and many even now (in the early 1960s) consider themselves Roman Catholics, but they then typically add that the Church is too strong in its current assault on African tradition and that the CMS is much preferable in that regard. In fact, the Anglicans in the Eastern Region of Nigeria have reached a degree of accommodation with traditionalist groups, at least to the extent that some native ritual forms are strongly penetrating CMS rituals at the village church level and that Anglican leaders have accepted the right of local members to perform certain kinds of traditional worship and still participate in Communion and other Christian ritual forms.

The Roman Catholic Mission is however quite opposed to such accommodation, and is instead engaging in a frontal assault on the traditional Igbo world, an assault which many of the hinterland Ndi-Igbo immigrants to Onitsha clearly approve. Many young migrants from the hinterlands to Onitsha display the evidence of intensely competitive proselytizing in their very selves: they tend to be either committed Catholics or committed Anglicans, and many join “Youth Fellowships” in Onitsha which dedicate themselves to “defeating” the other side. Quite noteworthy to us among these young Ndi-Igbo is an idealism regarding the progressive potential of Christian values, an almost unquestioning faith in the virtues of the West. (This is not universal by any means among Ndi-Igbo,but it is very much a popular view.)

It would take us too far afield here to describe in detail the history of these developments (see Chapter 2, “Deep Searching”,, pages on “European intrusions” and beyond for more discussion) but to draw a brief contrast:

************

The CMS pioneered in teaching the gospel in the Igbo vernacular, and encouraged early Africanization of the lower levels of the clergy. Its orientation to social change in the colonial dependencies was to encourage a gradualistic development under enlightened (and often remote) English tutelage while maintaining those roots in African tradition which did not violate the colonial conception of “natural law”. The French and then Irish Fathers of the Holy Ghost Roman Catholic Mission (though intruding later into a CMS-occupied domain) gained a larger share of converts over the long run by using white missionaries who lived in the local scene, dispensed Western medicines liberally to their converts, to some extent suborned CMS catechists by night, teaching their charges in English and crash-training Africans for the skills they would need to work in the colonial bureaucracies. Broadly, the RCM followed more realistic-practical procedures, while the CMS remained for many years stuck in somewhat anachronistic ideals (educating their chargess primrily in trhe vernacular, stressing arcane virtues like “self-denial”, etc.).

The RCM policy of directly modernizing the African population proved more appealing to most Africans of the early 20th Century than that of the CMS policies of a gradual transformation beginning with a traditionalist base (emphasizing gospel-teaching in the vernacular, a theory paralleling the ideals of British Indirect Rule), because it conferred an early competitive edge to its converts — material assistance, especially in obtaining jobs (and the policy was also substantially more popular with the Colonial officials because they very much needed skilled African clerks).

To cite just one example, one of my best traditionalist informants, Akunne Oranye of Umu-Ase Village, who was at age 75 one of the oldest retired colonial civil servants in Onitsha, told me he had begun his training in the CMS in 1898. But his parents saw that (as he put it) while the CMS taught in the vernacular and had only one white man on their staff, the RCM taught in English and had many whitemen. The obvious inference was that their son would learn the white man’s ways more quickly in the RCM. So in 1900 he was switched to the Catholic school system in order to get the kind of training which would (and did) enable him to get a good government job (which enabled him and his family to prosper). A large number of Ndi-Onicha followed this sequence from the late 19th into the early 20th century, with the significant consequence that they gained perspective on both versions of the Christian faith and its proponents, an overview of the dualism and its conflicts not yet available to most of the (somewhat later) Ndi-Igbo immigrant converts .

In addition, in its assertiveness the RCM quickly moved into active participation in local political struggles (unlike the CMS, which in keeping with its position as an establishment religion under the British Crown adopted a more passive, officially apolitical stance): early alliance with a strategically placed Niger Company officer who was also a Roman Catholic helped them gain an initial foothold, followed with successful backing of their convert Samuel Okosi for the Onitsha Kingship in 1900. Continuing to build strong relationships with pivotal colonial officials, Roman Catholic Christianity rose to dominance in Onitsha Province by the 1930s, and by the 1940s their consistently assertive policies toward Westernizing the African population gave the RCM a substantial lead in the educational field in Eastern Nigeria, though the CMS managed to remain competitive, and RCM aggressiveness also generated a deep political split within Onitsha Inland Town, and created considerable disillusionment and antipathy toward Christianity among the people there, including as the struggle for Independence grew, overt hostility toward the RCM. Nnamdi Azikiwe’s attitude toward the RCM is emblematic of this.

Their very success in pursuing a strong form of Westernization encouraged the Catholics to adopt a very strict rejection of what they deemed obnoxious patterns of traditional culture. In some measure Roman Catholic abhorrence of traditional Igbo culture seems to have been deeper, broader, and more categorical than that of the CMS from the beginning (the CMS difference partly related of course to the latter’s use of repatriated Africans as their first missionaries, some of whom showed considerable interest in traditional culture), and this RCM rejection intensified during the 20th century. After the RCM’s successful sponsorship of a convert as the Obi, tradition-conserving Ndi-Onicha (and especially those whose side had lost the 1900 contest, namely members of Umu-EzeAroli) became increasingly antagonistic toward the Catholic Church.

During the nationalist struggle for Nigerian Independence (led in its early phases by Zik in association with a number of other prominent Onitsha and other Igbo men), the white Reverend Fathers’ rejection of African traditional forms, their calculated political militance against what they defined as the threat of “Godless Communism”, and the contradiction inherent in the Catholic mission policy (systematically training Africans in skills of the modern world while reserving a near monopoly of the higher levels of the priesthood for the Irish expatriates) brought them under increasing criticism in the 1930s. Throughout the nationalist struggle, Zik’s West African Pilot repeatedly criticized the power of the Roman Catholic establishment in Onitsha and elsewhere, while RCM leaders repeatedly accused NCNC radicals of embracing “Communist Atheism.” While nationalist leaders encouraged greater degrees of pride in “traditional African customs”, the Church attacked this as “Paganism”.

The CMS was more accommodative to (at least it less vigorously resisted) the movements toward Independence. To some extent by the time of Nigerian Independence, Anglicans in the Eastern Region of Nigeria were accepting some traditionalist activities, to the extent that native ritual forms were penetrating CMS rituals at the village church level and Anglican leaders had accepted the right of local members to perform certain kinds of traditional worship and still participate in Communion and other Christian ritual forms. The RCM was however quite unwilling to allow much accommodation, and was instead demanding increasing militancy on the part of its parishioners, urging them to eradicate non-Christian acts.

As Nigerian Independence approached, a very strong undercurrent of concern arose within the RCM about the relative “balance” in numbers of Protestants and Catholics occupying ministerial and other official positions in the regional government, now dominated by Nnamdi Azikiwe’s NCNC. While there were substantially more Roman Catholics than Protestants in Eastern Nigeria (and more Catholic primary schools than those of all the various Protestant Churches combined), Protestants were much more strongly represented in the cabinet of Zik’s 1956 regional Government, and the RCM (which kept careful account of this numerical representation) was dissatisfied with the NCNC’s official leadership. The fact that Zik’s own loyalties were unambiguously Protestant (with a history of occasionally baiting the Catholics in his newspapers), together with the overtly religious Apotheosis rendered to him personally by some of his more fanatic followers, no doubt intensified their opposition: The National Church of Nigeria — founded in 1948 — took Zik as their prophet and regularly likened him to Christ (Coleman 1958:302 3). Zik, though denying he was a “New Messiah”, nonetheless saw fit to observe in his autobiography that “the eve of my birth was signalised by the flash of a comet….” He definitely had a somewhat messianic sense of his own political importance (Azikiwe 1970:7).,

But the heart of the problem was the movement of his Eastern Region Government from 1954 onwards toward a “Universal Primary Education” (UPE) scheme which would shift control of primary schools out of the hands of the missions and into those of local governments, thus denying the RCM its main way of claiming a majority of converts6.

Faced with the reality of a UPE Law enacted in the Eastern Region in 1956 which appeared to foreshadow expropriation of their main infrastructural base (school-children), and observing that Premier Zik’s cabinet was predominantly Protestant, the Roman Catholics mobilized to contest the 1957 Eastern Regional elections. Late in 1956, a group of leading lay Catholics assembled in Onitsha and formed the Eastern Nigerian Catholic Council (ENCC), charged with the task of increasing the representation of Catholics in the NCNC-dominated Regional Government. 6 This action quickly begat its antithesis, a Convention of Protestant Citizens (CPC), organized in early 1957 to oppose what one of its members later called the ENCC’s “crusade of total political annihilation of Protestants in Eastern Nigeria.”6

In its last issue prior to the March 15, 1957 polling day for these elections, the weekly regional newspaper of the Catholic Church, The Leader (whose circulation was eventually claimed to reach 30,000), editorialized that 7

“It is an incontestable fact that the main issue at stake in the election is that of education. The natural rights of Catholics have been violated, their protestations ignored. They and their church have been the object of a lie and smear campaign. On March 15 the religious future of their children is in their own hands. After March the 15th it is in someone else’s!”

While Church involvement in this election did not show an immediate, overwhelming effect at the polls, Catholic candidates were sufficiently successful 8 that in its aftermath the cabinet of the Eastern Nigeria Government evolved to a more equal balance between Protestants and Catholics, but while after Independence most political organizations officially aimed to “expunge religious issues” from party organization, new interest groups representing both denominations began contesting elections more openly. Intense competition between the RCM and the CMS in the Onitsha hinterlands directly affected many young migrants to Onitsha, who proclaimed themselves either committed Catholics or committed Anglicans and joined “Youth Fellowships” in Onitsha which organized themselves into quasi military formations and dedicated themselves to “defeating” the other side. 9

***************

When we arrive in Onitsha in September of 1960 on the eve of Independence, we find that the Onitsha branch of the NCNC has just been dissolved due to RCM/CMS conflict within its leadership, and replaced by a Caretaker Committee whose task is to resolve the dispute. During the Independence celebrations and shortly afterwards, people we meet spesk confidently that these sectarian religious conflicts are a thing of the past, but issues of religion again intensify in Onitsha when on January 5, 1961 the Nigerian Spokesman reports the Eastern Nigeria Government’s announcement that a number of County Council elections (including Onitsha Urban) will be held during the coming Fall.

On the following day, the Spokesman prints an editorial which, after duly exhorting the local populace to “rally round the N.C.N.C.” and denouncing the current propensities for discontented party activists to form “mushroom organizations,” concludes with a solemn warning “against infiltration of religion into our local politics in any form.”

As if in response to this establishment admonition, both local newspapers are soon filled with

controversy over the relationship between political and religious affiliations. Initially this focuses on an internal conflict in the NCNC Onitsha Caretaker Committee involving Madame Margaret Obinwe, a prominent Onitsha Inland Town trader who is Vice Chairman of the local Women’s Wing of the NCNC and also a member of the Caretaker Committee.

Madame Obinwe’s Situation

Madame Obinwe, a very impressive Onye-Onicha, is the widow of the previous Onitsha Onowu (who died in 1953). 10 On January 12, Madame Obinwe announces to the press (in the Eastern Observer) that, though she has been a confirmed Roman Catholic since her baptism in l9l0 (the year of her birth), now despite many years of faithful service to the Church she is being suspended from making Confession and receiving Holy Communion because of her political views. She is being victimized in this way, she claims, because she has spoken out against the activities of certain Reverend Fathers in Onitsha, who are advocating that Catholics pursue “policies of non-fraternization” with Protestants, and who are, she say, working to place Roman Catholics in all the critical positions of political power in Eastern Nigeria.

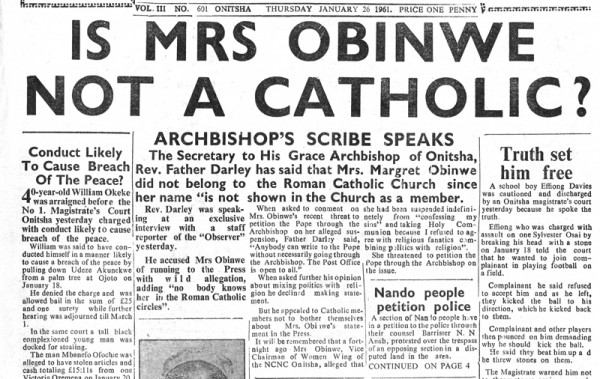

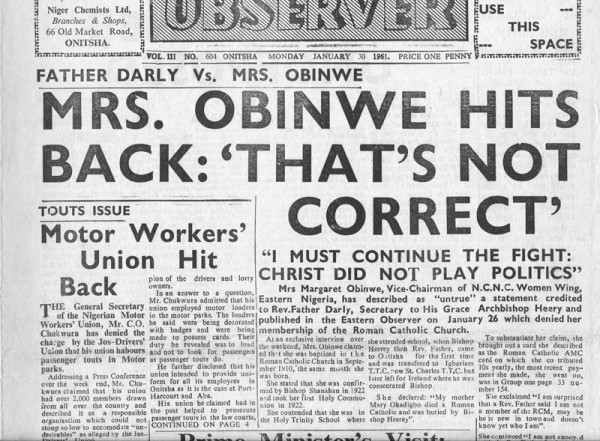

Madame Obinwe further says that she had first tried as a loyal member of the NCNC to air her case in the Nigerian Spokesman, but because of the delicate situation in the NCNC party’s Caretaker Committee the Editors of that paper have refused to bring the party’s religious conflicts to public light. So she and some of her supporters have arranged the broadcasting (over the Eastern Programme of the Nigerian Broadcasting Corporation) of a radio news flash that the NCNC intends to petition the Pope with a complaint about the conduct of the local Church authorities. When local NCNC officials then publicly deny this assertion, she has turned to Onitsha’s local Opposition Party paper, the Eastern Observer, and the Editors of the Observer oblige her with banner headlines, reports of interviews they held with local Church officials, and a series of Letters to the Editor written by various readers. For example, on January 26:

The Observer quotes the Secretary to His Grace Charles Heerey, the Archbishop of Onitsha, as denying that Madame Obinwe is a member of the Church, or even known to church authorities. Madame Obinwe responds with a long list of events and accomplishments. Here is one of her Observer statements 11:

Here she presents her considerable biography of association with the church (and her mother’s connections as well), and a list of events and accomplishments which demonstrate that her own affiliation with the Onitsha RCM is of much longer duration than either of “these Irishmen.”

One Observer correspondent then writes a long article calling for rapid Nigerianization of the Church, while another demands that the Archbishop’s Secretary explain “to members of the Roman Catholic faith the policy of non fraternization expounded by a Reverend Father during the last December retreat at the Roman Catholic Church (in) Fegge (Onitsha Waterside).” 12

Local Roman Catholics then respond to the Observer’s publications, one explaining that the “non fraternization with dangerous and illicit religious people” recommended by the Reverend Fathers has referred not to Protestants but to “superstitious dealers, juju priests, and fortune tellers.” Another submits a long article headlined, “You are Wrong, Mrs. Obinwe,” arguing that “taking for granted that (the Reverend Fathers) do take part in politics there is nothing wrong in that because religion and politics are indivissible (sic) partners catering for the welfare of man.”

Madame Obinwe and her supporters continue to pursue their objectives by pointedly establishing a new organization which they called “The Onitsha City Mothers Association, in Alliance with the NCNC,” and which demands (beneath a big headline in the Observer) the removal of Mr. C.C. Anah (a prominent Roman Catholic activist and politician) from his post as Organizing Secretary for the Onitsha Branch of the NCNC. Mr. Anah replies through the Spokesman, warning Onitsha women to desist from organizing “unconstitutional” women’s branches of the party.

There is a wider context to these local disputes. Both at the national and regional levels, Nigerian newspapers are carrying accounts of conflicts between the Roman Catholic Church and the governments of various countries around the world. In Onitsha, these reports appear like scattered echoes: an article on the same day the September elections are announced headlines that “CEYLON GOVT. TO TAKE OVER CATHOLIC SCHOOLS” (without paying compensation); letters attacking and supporting the Reverend Fathers for their sermons against the admission of Communist Russian agencies into Nigeria; and scattered accounts of progress and dynamism in the Soviet Union, for example a headline “RUSSIAN SCIENTISTS SAYS (sic) DEATH CAN BE OVERCOME” (i.e., by means of transplantation of animal organs).

Many Nigerians we encounter at this time speak of the Soviet Union with fascination, for they have occasionally seen its then-unique earth satellite moving through the night skies overhead. There is a somewhat vague wondering if the Soviet system might constitute a viable alternative way of life, and the intense RCM antagonism toward communism probably to some degree increases the interest in this alternative.

2. “Religious Politics” in the Inland Town

While the Inland Town is in some measure affected by these developments (Madame Obinwe and most of her strongest supporters being Ndi-Onicha residents there), religious affiliations are differently viewed in Enu-Onicha than they are in the Waterside, in part because so many Onitsha people have experienced sufficient education and training in both RCM and CMS contexts over the years that they can hardly avoid taking more balanced (if in some cases derisively skeptical) views.

In my early work I find that most traditionalist Ndi-Onicha informants who discuss the subject affirm to me that they have been raised during at least part of their careers as Roman Catholics, but they then add that the Church is too strong in its current assault on African tradition, and that the CMS is much preferable in that regard. Despite this criticism, many claim even now to be Roman Catholics, and to be regular attendants at St. Mary’s Sunday Mass. (Such commentaries and such ambivalence are rarely expressed by Ndi-Igbo immigrants to Onitsha whom we interview. By an overwhelming majority these latter are committed to one or another Christian denomination, and most of them strongly distance themselves from their Igbo traditions, which they tend to depict in negative light.)

Obiekwe Aniweta, who has only recently ceased teaching in a Roman Catholic school, announces to me one morning in mid April that he must postpone our census work for a while because, he said, there are “movements afoot” in the Inland Town which he intends to forestall. The Reverend Fathers are, he claims, trying to push Moses Odita into the kingship, and Aniweta intends to determine the facts and then write about it, “to expose them all.”

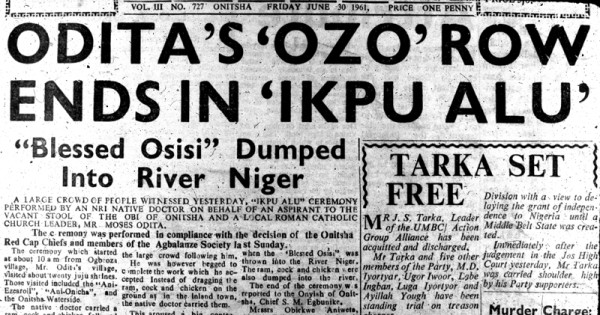

On April 27, the Eastern Observer presents this headline:

This (previously unheard of) organization, “The Onitsha Aborigines Society”, proposes to send a protest delegation directly to the Archbishop. The notice continues:

“A meeting of the Society held early this week expressed great concern over the current rumour in Onitsha to the effect that the Roman Catholic Church had sponsored one of its members to contest for the vacant stool.

“Members wondered about the authenticity of the rumour, but observed that if the rumour was correct, it was nothing short of a foreign religious body meddling with the sacred institution of ‘our land’.”

On the back page of the same issue there appears another headline:

STRUGGLE FOR ONITSHA THRONE HEATS UP:

CATHOLIC CHURCH IS WARNED TO KEEP CLEAR OF THE BATTLE OR….

The accompanying article describes a press release made by Mr. Obiekwe Aniweta, who is attacking the Roman Catholic Church for adopting a “policy of intervention in the politics and government of the Onitsha people:”

“Before the death of the King of Onitsha, the entire public of Onitsha have been complaining about the unenviable role the Catholic Council has been playing both in the Local Councils and in the Regional Parliament itself. But the people in authority in the upper heirachy (sic) of the church always refute these allegations and try to explain away the points.

“But the stool of Onitsha is now vacant and a successor is needed. There are many aspirants to the vacant throne. But the only possible candidates are Mr. J.J. Enwezor a director of a contracting firm in Eastern Nigeria; Mr. J. Onyejekwe a police officer and finally Moses Odita.

“It is worthy of note that the last named has been to Rome on a religious mission, on the Catholic platform.”

Aniweta then observes that in l900 Okosi I was installed King of Onitsha “through the instrumentality of the Catholic Church. By that time Religion was inseparable from Government and our people were living in fear and ignorance.” Okosi II had also been “a papist;” the question to be asked now is, Who will be the next King of Onitsha?

“Those of us who are familiar with Onitsha custom will agree with me that Roman Catholicism is incompatible with Kingship of Onitsha.

“It is traditional for any body aspiring to occupy the Throne to be a ‘Medicine Man.’ By this I mean that the person must be a juju priest. He must in short be an ‘Ozo man’ i.e. a title man.

“Again the person must have performed the second burial of his wife or wives. This condition is precedent to the assumption of the office of King of Onitsha. It is therefore plain beyond doubt that the Roman Catholic Religion forbids all the above.

“Yet in Onitsha events have assumed unmanageable proportion. The scriptural principles are now being side tracked. An influential member of the Roman Catholic Church has been allowed to perform the second burial of his wife yet the church still allows him to take holy communion in the Church….”

“Another rumour current in the town is that the Roman Catholic Church is sponsoring a papist in the contest for the Kingship of Onitsha. It is impossible for a papist King to reign in Onitsha any longer.”

Aniweta concludes his press release with a threat to the Archbishop (after first exhorting him to “investigate and take necessary steps)”,

“But should the Roman Catholic Church (of which I am an active member) decide now to sacrifice her religious principle on the shrine of political prejudice, I will be compelled to become the Nigerian Martin Luther or another Henry VIII.

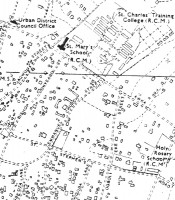

On April 29, the Observer reports that Archbishop Heerey has written the newspaper denying the allegations that the Church intends to sponsor one of its members to contest the Onitsha throne, affirming that it is in no way interfering with the succession process and that it has no intention of doing so. He warns the Observer against making unfounded accusations against the Church. And at the Sunday morning Mass held at St. Mary’s Church (see map at left), Father William Obelagu reads to his communicants a similar letter from the Archbishop stating that the Church would recognize whomever might be appointed to the throne, “no matter what his antecedents or religion.”

Fr. Obelagu is an Onitsha Indigene, highly respected in Onitsha. More than a year after the events being discussed here, on December 21, 1962, the Nigerian Spokesman reported the full text of an Address presented by Moses Odita to Right Reverend Monsignor William Obelagu on the occasion of his Sacerdotal Silver Jubilee. Here I excerpt some statements in scattered quotes: “on December 19, 1937… you were raised to the Holy Orders.” “Your first station was Aguleri … 1938, … then Oturkpo”… 1940 you were posted back to Aguleri.. For about 10 years you toiled alone in that great and fertile Masters Vine Yard. All the impassable bush paths in the Anam area were your thoroughfares…. On 1949, posted to St. Mary’s Parish, Onitsha”. Many speakers praise his contributions to the building of the impressive complex now comprising St. Mary’s in Onitsha. The Ajie, Ogene, Ojudo, Akpe, and Oduah are there (“and many other red cap chiefs”). “Mr. R.R.N. Olisa, M.B.E., Knight of St. Sylvester… says Monsignor Obelagu descended from Obi Chimedie of Umu-EzeAroli.”…His family lived in Ogboli Quarter from where the church sprang up, and for the time being, the church was known as Ogboli mission” See on the accompanying map above, at lower right, “Holy Rosary School” for the approximate location of the earlier church.

This interchange between the RCM (in the form of Fataher Obelagu’s statement) is revealing for several reasons. First, Aniweta adopts a stance both within and in opposition to the Catholic Church (coloring the two poles with heroic images of the Reformation). His voice from within adopts a rather Inquisitorial tone: will the local Church allow its “scriptural principles” to be set aside? His outsider’s voice attacks the RCM from the perspective of a tradition- oriented Onitsha man, perhaps that of a member of the Onitsha Aborigines Society. (When I ask Byron Maduegbuna what he knows about the “Onitsha Aborigines Society,” he grunts that it is probably “something cooked up in the minds of Umu-Anyo“. (The latter is of course Aniweta’s Village in Umu-Aroli.) Later confronted with this view, Aniweta smils and admits it is a construct he has found convenient to fabricate for the purposes of the moment.)

Second, Aniweta accuses the agents of the Church of chronically employing deceptive tactics, in this case for the underhanded purpose of installing one of their members as King by allowing their chosen candidate to perform “pagan rituals” they have strictly proscribed for ordinary folk, and he describes their standard mode of response when they are publicly accused of such deceits. Third, the reported responses of the Archbishop appear to follow the course Aniweta has predicted.

3. Lamentation (Ikwa-Ozu), Ozo Title, and the Church

On May 2 both local newspapers present extensive discussion of the allegations about the Church’s sponsorship of a Kingship candidate, and cite from two open letters written by Obiekwe Aniweta and Arinze Onuorah from Lagos. Both letters affirm that the customary Ikwa-Ozu (“Lamentation” ritual) of the late Mrs. Cecilia Odita (Moses Odita’s previous wife, who had died in June of 1959) has just been performed at Ogbeozala in Onitsha beginning April 20. Observing that he can recall a large number of prominent deceased Onitsha Roman Catholics who never received their appropriate Ikwa-Ozu rituals “because it is against the law of the Church and the punishment for offending the Church law is excommunication,” Onuorah points out that

“The Onitsha native law and custom forbids a man who has not performed the native burial ceremony of his deceased wife from joining the Agbalanze Society (OZO TITLE) or from competing for the Office of King of Onitsha because he is not clean.”

This passage clearly identifies the dilemma now facing Moses Odita: if he wants to contest the Onitsha Kingship, he must engage in traditional activities of ritual self purification, and these should bring him immediate Excommunication from the Church. He must take the Ozo title, and in order to do that he must perform the Ikwa-ozu (also rendered in English as “Second Burial”) of his deceased wife.

Onuora Arinze continues: 13

“It is alleged that this prominent Christian (i.e., Moses Odita) has explained to his parish priest (Father Obelagu) that he was not responsible for performing the native burial ceremonies of his Christian wife and as a result he is allowed still to receive the Holy Communion.

It is probable that the Archbishop is not aware of this incident. The public would like him to investigate it and make a statement in all the churches otherwise the community of Onitsha will continue to believe that the Church is extraordinarily interested in a particular person for the appointment of King of Onitsha.”

In his companion letter Obiekwe Aniweta carries this point further:

“The ‘Igbudu’ insignia (symbolic coffin) was arranged and this has connection with idolatry which the Catholic Church forbids.

But in the church on the 30th April, Mr. Moses Odita, the husband of late Mrs. Cecilia Nwanyife Odita, received the Holy Communion.

I wish therefore to know from His Grace the Archbishop of Onitsha whether it is proper for Mr. Odita to receive the Holy Communion when it is plain that the Ikwa-Ozu of his late wife had been performed in the traditional way.”

Aniweta concludes his statement by warning readers against “a conspiracy of silence on the issue” and, adopting the stance of a True Believer, he calls for “positive action” by the Church “in order to preserve the Christian ideals from a satanic scourge.”

The Church’s direct response to these allegations merely denies knowledge of the ritual in question, but a Church spokesman does state publicly that he knows Moses Odita has performed a Christian ceremony, unveiling a memorial to his late wife. This, he reported, was done on the afternoon of April 30, when the Reverend Monsignor Obelagu and Moses Odita led a procession of mourners to Onitsha’s New Cemetery, where they viewed the newly installed life-size statue of the deceased.

Here both accusing letter writers pursued Aniweta’s earlier tactic: by publicly identifying the contradictory requirements of the two religions, they make it very difficult for the Church to do what many Onitsha people believe to be its intention, namely to ignore technically “excommunicable actions” being done by Moses Odita. But the Church’s replies merely follow their previous course.

The unveiling of busts or statues of socially prominent deceased persons is a well established practice in Onitsha, and such occasions are often blessed by local clergy of both Christian faiths. Performance of Lamentation ritual (ikwa ozu) is however an explicitly pagan celebration which by 1961 only the Anglican mission have become resigned to tolerating within its ranks. Lamentation (lit., “Crying for the corpse”, usually translated as “Second Burial” in native texts) is intended above all to escort the wandering ghost of the deceased person into the Land of the Dead with gifts of care, food, utensils, and symbols of social position. Until it has been done, the ghost hovers in the vicinity of its previous world, allowing the survivors (who are tinged with the “dirt” of its presence) little peace. Therefore an appropriate send-off of the deceased relative is a cleansing process, and traditionally an essential prerequisite to the pursuit of such greater self purifications (or “hand washings”) as the taking of Ozo title for men, the prime label for access to all formally institutionalized roles of higher leadership.14

The pivotal funerary ritual revolves around the Igbudu, a box framework wrapped with burial mats and which represents the original burial coffin. At the climactic moment, the ghost is ritually invoked into this container and given gifts for use in the next world, and (accompanied by much prayerful exhortation) the box is finally interred at (or near) the actual grave site. This ritual, which includes a blood sacrifice over the symbolic coffin prior to its interment, has been unequivocally condemned as idolatrous by the Reverend Fathers of Onitsha since their early days, and they might only continue to accept Moses Odita for Confession and Holy Communion if they now remain officially unaware that the act has occurred, or if they can attribute responsibility for it to some other person.

After a man has finished his obligatory Lamentations, he may then proceed on the path of ritual self purification toward obtaining his Ozo title, which makes him eligible to pursue further paths toward chieftaincy and even possibly kingship. All of these roads are (using this verb in the sense of a “traditional” present tense) strewn with blood sacrifice and other offerings to gods, spirits, and ghosts, the use of magical medicines, and other “idolatries” abhorrent to the Church. In brief, what is traditionally defined as “cleansing” in Onitsha religion is by 1961 defined as a “stain” on one’s character in that of the RCM.

This stark cultural confrontation was embedded in the history of the colonial era, and its rationale (already implied in previous chapters) will bear further exploration. At this point in the narrative its significance is that it means, in effect, that the Chiefs and other Ozo men of Onitsha (the most prominent official authorities of Enu-Onicha aside from the King) necessarily stand outside the realm of direct Roman Catholic Church influence. The Church however has tolerated King Okosi II, presumably because of his descent from the first Roman Catholic King (Okosi I), because he claimed to follow the latter’s innovation of not directly performing sacrifices (“the king has no juju” was a proverb-innovation of the Okosi line), because he continued to profess his Catholicism and had close Roman Catholic advisors, and because the Church simply turned its back on some of the activities done in his name. But the Church has remained unbending in its insistence that Onitsha indigenous “idolatries” specifically, those connected with funerals and with title-taking are agencies of Satan, and refuses to accept those who overtly practice them within its ranks. To do so would open the door to floods of sacrificial blood.

The tension accompanying this problem has risen for a number of years, especially (as we have seen) as National Independence approached and active practice of “traditional” (“pre colonial”) Onitsha customs gained concomitant momentum. During the late 1950’s a number of prominent Onitsha Christians made efforts to reconcile the Ozo title with the demands of the Roman Catholic Church, since (given the numerical predominance of Catholic converts in the community) the Church’s rigid stance on the issue was stimulating much intra-family conflict.

Early in 1960, Archbishop Heerey wrote a letter to King Okosi II suggesting how the ritual of Ozo title taking might be changed to make it acceptable to the Church. In this letter, the Archishop began by noting how from time immemorial the Ozo ritual entailed “a number of acts of idolatry and superstition which have made it impossible for a Catholic to take it and remain a Catholic,” and submitted for the consideration of the Onitsha king, chiefs, and titled men a proposed Declaration which affirmed that, while any title taking Catholic might pay the necessary sums of money and distribute it to the Ozo men in the customary way,

“no part of this money is to be set aside for any deity, spirit, or deceased ancestor. No native sacrificial food may be allowed at any feast, and there will be no insignia such as ‘Osisi’ (Title Staves) that has connection with idolatry or ancestor worship. The ankle strings and eagle feather may be allowed, but these will be blessed with Holy Water and must not touch any idol or shrine.”

Finally (the Archbishop concluded), the Ozo man must make no claim to participate in a “priesthood.”

In reply, the Secretary of the Onitsha Ozo Title Association wrote the Archbishop that his colleagues had carefully considered the contents of the proposed Declaration, but they regretfully “inform you that the Said Declarations are most unacceptable, and beg that further correspondence on the subject may cease.”

Shortly after King Okosi II’s death the issue was raised again, almost casually, in the local daily papers. On March 8 in the “Vox Pop” of the Spokesman there appeared an article entitled “The Church and Ozo Title,” under the pseudonym “Ofo Diali” (an allusion to the senior lineage priesthood of the Diali branch of UmuEzeAroli, part of a subdivision of Ogbeozala to which, notably, Moses Odita belongs). We have outlined this previously in this Chapter (in the page on “Umu-Eze-Aroli and other Royals”), but some additional comments are now relevant here.

The article asserts that “thousands of adherents are deserting her as a result of anachronistic wrong concepts by the Church of the traditions and customs of the African.” Noting that the Church has singled out Ozo title as “an abomination in the sight of God,” the writer attacks the Church’s basic argument to the effect that “goats and fowls are killed before wooden images which the Africans worship.” These inaccurate views of African religion were, understandably, conveyed to the Reverend Fathers when they first arrived, through the “inadequate language of the early semiliterate interpreters”, but such misunderstandings should now be corrected:

“The fact is that the Africans do not worship images, but regard them as media through which they lift their hearts to God and their departed relations.

The images represent dead relations who live exemplary and saintly lives, believed to be resting peacefully with God.

The Church has her saints whose many statues adorn her houses of worship.

The Church condemns the wooden images of our forefathers because their beauty does not measure up to that of statues imported by the white man.”

It is by means of similar logic, continues the author, that non-Catholic Christians are condemning Catholics for worshipping the images of saints. The misunderstanding in both instances is at root a difference in aesthetic standards, not one of moral differences. Moreover, the Church condemns the killing of goats before wooden images, but does not condemn Abraham and the others described in the Old Testament who made such sacrifices. In fact,

“When Africans slaughter goats or cows before wooden images of their fathers, the cows and goats are not offered to the images because the images which are inanimate cannot eat.

They are offered to God through the blessed dead, as was done by the ancients of the Old Testament.”

Therefore, the author concludes, it would be stupid of Africans to condemn their customs simply because the Church misunderstands them. The Ozo Title is a glorious and noble custom, “the ambition of every Onitsha man:”

“For the Church to continue to frown at Ozo title taking is nothing short of the outmoded old imperialist condemnation of everything African.

This is an enlightened generation and the Church should not continue to live in the past.”

When this article appears I am strongly impressed by it, because it states with sophistication and elegance what many Onitsha men have been telling me since my first arrival in the field. At the traditional rituals I attend, participants often give more attention to pointing out correspondences between Onitsha customs and those of the Christian churches than they devote to expounding the traditional beliefs and values (which often appear to be poorly understood, especially by the more educated men raised largely outside Onitsha who form the predominant social class now taking the Ozo title). They call the Ozo title a “Holy Order”, describe its rituals as acts of “consecration” with each candidate undergoing “anointment” and “purification” until “ordained” by his descent group “priest.” They equate the Title Staves of Ozo men to the shepherd’s staves carried by bishops, the Chief’s leather cap to the bishop’s mitre, the Igbudu of Lamentation to the Catalfalque of the Roman Catholic funerary Mass, and so on.

With great confidence, Onitsha titled men are constructing and proclaiming a system of correspondences between their own ritual practices and those of the Christian clergy. (The most widely remembered public proclamation of this sort occurred in 1945 ‑‑ as active nationalism was upwelling in Onitsha ‑‑ when Reverend V.N. Umunna, an Onitsha Anglican Deacon from Ogbeoli-Olosi, presented before a meeting of the Onitsha Youths Literary Circle a detailed set of ritual correspondences between Onitsha customs and their Old Testament equivalents. See Onyejekwe, JO. 1987:100‑101. ).

The descriptions of the title process I receive are highly varied (depending largely on the background experience of the speaker), but as I collect material I am impressed with the elaborate cultural meanings associated with these rituals as transformations of the self, and with their emphasis on the social responsibilities of title holders. While I recognized that the models of leadership implied in the Ozo title are by no means the same as those formulated in Christian frameworks, the suggestion that the Ozo title process is a Satanic scheme seems to me quite incredible, even ridiculous. Certainly the contemporary rituals I was witnessing does not fit this kind of mold of Evil-doing to any degree, as far as I co see. (While I do sometimes privately cringe while the sacrifice of animals is performed in my presence — often with poorly-sharpened knives, I find it hard to believe that the ritual-free mass killing of similar animals in United States meat factories is in any way morally superior to these individually-directed sacrifices, which are followed by careful distribution and consumption of the animal ody-parts ).

In some ways, the RCM’s view of indigenous religions seemed to me almost Medieval. This sense of what we might call Paranoid thinking — demonizing the Other — became palpable in the set of experiences I present here below.

4. Anthropologists Observe The Holy Ghost Fathers’ Anti-Juju Crusade in Nnewi

I have remarked that from the beginning of our fieldwork we try to avoid being identified with either of the two major Christian denominations (emphasizing to anyone who asks that as anthropologists we are of course students of all religions, though especially interested in the study of non-Christian ones), assuming from my modernist perspective that I will be seen as an “objective presence”, since that is what I think I am.

I begin to sense, however, that the Catholic priests in Onitsha during the early 1960’s have no hint of an anthropological tolerance of traditional Igbo religion in fact, they accept the most negative stereotypes professed (for example) by Ndi-Onicha and Ndi-Igbo toward each other, and identify these as the core features of native traditions (human sacrifice and cannibalism, etc., as discussed in other chapters). More profoundly, many of them appear to be strongly obsessed with visions of native magicians controlling uncanny powers, actually themselves believe in the real existence of these powers, and seem determined to root out these “Satanic” forces from their entire domain in Eastern Nigeria. Their efforts to fight against Satan have apparently intensified with the advent of Nigerian Independence, associated with a sense that problems of sociopolitical morality will soon bring the country to a crisis and that strongly decisive action on their part to intensify commitment to Christian values is essential at this time.

On July 3, 1961, I happen to see a brief report in the Spokesman about a Retreat held at the Odoakpu Roman Catholic Cathedral in Onitsha Waterside, where the Irish Reverend Father was reported preaching a powerful sermon condemning the keeping of idols and “juju” by Christians:

“His sermon went deep into the hearts of the church men and the following day members of the church who had idols gathered them from their houses and deposited them at the door of the Cathedral.”

The article says that this example stimulated others to collect their own objects of traditional veneration, to add them to a growing pile which will soon be destroyed at the church premises.

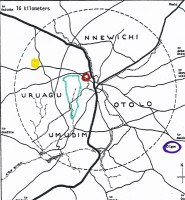

Interested in seeing what varieties of objects had been donated (and thus to get a sense of the kinds of traditional ritual activities are being imported by Ndi-Igbo when they migrate into Onitsha township), I go to Fegge to visit the Reverend Father there, hoping to examine the pile (and hopefully make some collections of ritual items for museums). But I am too late to see the jujus: a diffident man, the priest tells me he tried to avoid looking closely at them, feared their dangerous power, and supervised their burning immediately after their collection several days before. He adds however that the Retreat in which he was participating is being organized by another Reverend Father, who has very recently arrived in Eastern Nigeria and who is supervising a series of these activities in various parts of the region. He says that this priest is now conducting a similar Retreat among the school children of Nnewi (l5 miles SE of Onitsha in the Hinterland, a major center of Catholic activism in the Eastern Region and politically as well as economically a very important township).

Christian Juju-burning in Nnewi

Helen and I drive immediately to Nnewi with a Nnewi friend, Mr. Jonas Onwuka,15 where we meet this Reverend Father in the hallway of the main church, surrounded by an impressively large and expanding collection of traditional Nnewi religious art objects. These include not only substantial numbers of exquisite wooden masks and statues, in fact I am stunned by what I am seeing. Helen and I have agreed to collect some objects of Igbo art (Museum officials at Berkeley had allocated us the very modest sum of £ 100 for the purpose), but in our occasional efforts we have encountered only a few things worth collecting. Now, I see among the vast array of piled-up carved wooden objects, some of gorgeous, highly sophisticated quality. I remember one particular very large wooden mask of a ram’s head, indeed it remains to this day a haunting figure in my mind, it was obviously a significant loss to the art traditions of humankind.

In these piles were for example small objects clearly associated with personal gods of individuals and the masks of various social groups, but also the entire large scale statuary retinue of the Edo Spirit (Alusi), Nnewi’s most famous shrine. As we observe this active social scene, we see Nnewi school children busily bringing various objects in to the Mission church, having seized them from the altars of their fathers (in many cases without asking permission). A grand ritual burning is planned, to be held in the middle of the football field located nearby.

After introducing ourselves as anthropologists, I argue at length with the priest over the disposition of these ceremonial artifacts, being especially impressed by the aesthetic quality of some of the carved wooden masks. The Reverend Father replies that he can see no beauty in any of them, that they are the work of Satanic agencies and as such utterly abhorrent to him. Moreover, he strongly doubts that any ethnographic value might be obtained by discussing their nature with the “magicians” from whose altars they have been taken, arguing that these men would never tell the truth about their sources or utilization, and that the “magicians” themselves possess dangerous powers they will probably bring to bear against any questioner who approaches them.

In reply to my suggestion that the artifacts should be reserved for Nigerian museums, he maintains that so long as the objects are known to exist anywhere the people will continue to believe in the “demons” they represent. Ultimately I win from him the concession that the Edo shrine objects should be set aside for a museum collection, and also he says he will notify me when the final Retreat ceremony is to be held so I can come to the Mission beforehand and sort through the religious objects collected in order to save some of the most distinctive specimens.

The map of Nnewi16 at left shows some major features of the town. Nnewi is historically organized by a system of ranked clans, the four major ones dividing the territory, by order of seniority Otolo, Uruagu, Umudim, and Nnewichi. The Sacred Forest of the Edo Goddess (the ruling deity for all Nnewi) is located in Uruagu Quarter (home of its hereditary priests), but the Head Chief of all Nnewi (by the 1950s called “Obi“, though in earlier times all Nnewi chiefs were called “Eze“) comes from Otolo Quarter, and my understanding is that only he can “speak to Edo” (and dip his hand into the Udu pot kept in her shrine in the center of the forest). Note how the the Sacred Forest stands beside the Main (Nkwo day) Market of Nnewi, thus located where it sanctions its everyday operation (in traditional times).

We enter the Edo Forest during our visit there, accompanied by our friend and guide Mr Onwuka, who is a native of Nnewi.

At left Helen and Jonas Onwuka briefly tour a very small portion of the vast Sacred Forest of Edo, seeing a number of the traditional shrines including the shrine house shown at left. We look inside a small one of these houses, below right, where we can see evidence of very recent ritual sacrifice.

In this shrine image at the right here, note first the massive array of sacred, Awka-carved doors which bar the view into the inner sanctum. Just visible behind the open portion of the doorway you can see the lower portion of a large clay mound dedicated to the Goddess (or one of her minions). The bones of large animals sacrificed that hang from the rafter do not obviously convey their age, but cones of white clay lying below indicate recent ritual activities, and at bottom of the picture, a large array of white clay markings with accumulated masses of chicken feathers attest to many years of dedicated devotion continuing down to the present day (in 1961).

Some days later, in Onitsha, Jonas Onwuka appears at our home to inform us that the Retreat-burning ritual is scheduled for that very day, so we drive in haste to Nnewi in the late afternoon, where we find the Reverend Father at the church amidst a great bustle of activity. He evinces what seems to me a distinct (and surprised) expression of chagrin confronting our sudden appearance, but quickly recovers and says that he has “forgotten” to notify us of the ceremony. Many hundreds of schoolchildren are gathering for the climactic procession, and a small army of boys are carrying amassed ritual objects out from the church to the

football field where a large pyre is being built, and over which liberal quantities of kerosene are being poured. We manage with the priest’s permission to grab a few small items not yet removed from the church (For example, the image of a small ikenga, readily held in one hand, shown here bracketing the text as one example of the very few objects I manage to pick up at the scene. This one is so blackened with sacrificial blood (obviously not a discarded, unused object) that I later have to scrape it quite a bit to see its features; clearly it has been in perennial use by its previous owner.17, and I also manage (after much adamant insistence on my part; I tell them I will not leave the scene without it) to secure the large Edo Shrine figures, which we place in the back of our car as the twilight procession begins.

We then stand at the edge of the field as the children hold lighted candles and sing hymns while they walk in a great double line that begins to circle the running track surrounding the football field, following a leading group of girls who hold over their heads a tableau dominated by an illuminated statue of the Virgin Mary. In the center of the field, the pyre is lighted and a great billow of dark smoking flame begins to engulf the ritual objects, as young men run about throwing more things into the fire. As the Reverend Father exhorts the group, his brief words about the significance of these events for the moral future of Nnewi are given rich and extensive elaboration by his Igbo interpreter. As a number of bats begin flying through the illuminated smoke in the darkening sky above, children jump about excitedly, pointing up at the flitting creatures and repeatedly shouting “Ekwensu!, Ekwensu!” (in Union Ibo Bible translation, “Devil!”).

We return home with the Edo objects in the back of our Fiat 600. I hastily (and, sad to say, inadequately) photograph them (see the image below):

See here the well-dressed male and female Edo figures, their very massive dog companion to their left, and the great Edo Ekwe drum on the right. In the foreground from left, a statue representing the four days of the Igbo week, a medicine bundle in front of the large figure of Agwu, the vulture-headed figure representing native powers of medicine and divination, a pot for shrine water flanked by two clay-offering trays, and another wooden figure that I fail to identify. I feel uncomfortable having these objects in my house, and do not contemplate studying them.

I sit down and write a letter to Bernard Fagg, in 1961 the Director of the Nigerian National Museum in Jos, notifying him of what is happening in Nnewi. He in turn writes the Church demanding they desist from these activities (which are indeed in violation of the new Nigerian Antiquities Act). He also sends a museum representative to collect the Edo shrine figures from our house. The person who comes to our house to collect the objects is Philip Nsugbe, who is stationed at this time in the Museum at Oron in the Niger Delta. Sitting as a guest in our house at 24 Mba Road, he talks as though he thinks I have been planning to steal the objects, and later in print he claims for himself the achievement of having saved them from destruction.18

The RCM officials in Onitsha are unsurprisingly19 outraged at our interference with the central aims and accomplishments of these highly staged Retreats, and Helen and I find ourselves no longer welcome at the Roman Catholic Mission (where we have been examining old records to learn about the earliest Onitsha converts).

Initially stung by the priests’ rejection of us for our action (which I have regarded naively as a straightforward effort to initiate a communication between the Church and the agencies of Government which might prove beneficial to both groups), we begin slowly to sense that what has happened very likely does not reflect any “failure” of communication at all, but rather a tactic the missionaries have considered themselves compelled to adopt in the new Independence situation, where native traditional forms are now being accorded a newly positive respect by national leaders and where Roman Catholic powers are being challenged. Therefore they conclude that immediate (and even sub-rosa) actions must be undertaken against what they see as these newly-respected but implacably opposing and utterly evil forces. And, in fact, the RCM does not cease its destructive raids on Igbo ritual objects near Onitsha, despite the Museum’s warnings. On September 13, 1961, the Spokesman reports an event associated with the same Church:

The reporter says that an RCM Retreat at Uruagu, Nnewi has involved Catholic enthusiasts going from house to house to collect “jujus” in the absence of their rightful owners. In Onitsha, Reverend Father Patrick Smyth is quoted as saying that, while “it would be in the interest of the Church” if individuals voluntarily give up their jujus, “the church would be the last body to encourage lawlessness.” Obviously, if quoted correctly Reverend Smyth is in this particular instance lying.

They still continue pursuing these illegal activities in 1963, long after we have departed Nigeria. According to the Nigerian Spokesman of August 27 of that year. Under the heading, BURNING OUR IMAGES, the newspaper reports that the Nigerian Museum has been warning them, but “the missionaries’ response has not been very encouraging”.

This experience again confirms that what initially seemed to us a generally benign and cordial social scene as displayed in such activities as the Ozo title is viewed by some of its participants as much more deeply embedded in perceptions of danger and evil than we have been inclined to presume (and to which such rumors as “royal human sacrifice” and “Igbo cannibalism” have by now been introduced to us). In any case, by the time the events just recounted occurred, there is yet obviously another reason still for the Roman Catholic Fathers to feel suspicious toward us: my frequent and visible association with Obiekwe Aniweta and other (as they perceive them) “anti-Catholic forces” active in the Inland Town. Aniweta alone would be an associational curse, and I am seeing him frequently now since he is actively involved in his latest “spying”..

5. Moses Odita Performs his Ozo Emergence Ritual

Early in May we learn that Moses Odita, the devoted Roman Catholic dignitary who has announced his candidacy for kingship, is openly negotiating with the Ozo-titled men of Umu-EzeAroli to take his Ozo title. To many Onitsha people this implies that at last, the Roman Catholic Church is preparing to make a compromise with the indigenous community over the long standing issue of “idolatry.” During the month while his ritual preparations proceed, Odita’s standing as a prospective candidate for the Kingship rises continuously among those now participating in the Royal Clan meetings, many of whom hail him as an alternative far superior to Enwezor.

Committed Catholics who have long been torn between their devotion to the Church and their desires for prestige, authority, and influence within the Inland Town now express hope that his example will produce the fusion of the faiths which will soon make it feasible for them to take the title as well. Others who have admired Odita’s exceptional public service accomplishments, but have rejected his candidacy because of his religious commitments, begin to voice second thoughts about his worthiness for the throne. Throughout the Inland Town I witness a rising exhilaration, an awareness that a new era of reconciliation may at last be at hand.

At the same time, skepticism remains widespread. Seventy five years of experience with the RCM in Onitsha has generated a large number of converts in the Inland Town, but has also produced a notably large and rather vocal crowd of strongly (and vocally) ex-convert, now cynics. People ask how Odita’s Ozo-taking rituals will actually be conducted, and what shortcuts and omissions may be made out of public view. This negative perspective is of course especially prominent among Enwezor’s followers, though he and his core supporters emphasize their own status as Catholics when expressing it.

Aniweta hints to me that what he calls “a gross subversion of tradition” is being plotted, but he adds that “We have our own spies at St. Mary’s” (the main Inland Town parish of the Church, served as we have seen by Father Obelagu, an Umu-EzeAroli man who is Odita’s regular Confessor and advisor). St. Mary’s is directly across the street from Umu-EzeAroli.

Odita’s Ozo emergence ritual is performed on June 16, on the land of his people in the midst of Ogbe-ozala. In sharp contrast with Luke Emejulu’s20, it has not been widely publicized beforehand and so the crowd of commoners gathered along the roadway is considerably smaller, in fact I barely learn of it in sufficient time to attend. Many of those present however express unusual exuberance: one says, “This is a historic day in Onitsha!” and another, “For the first time, a Christian has taken Ozo title!”

When the Ozo men of the town come forth and join together to escort the candidate’s surrogate (the same man, by the way, who played this role for Barrister Emejulu earlier) in the grand procession to the Mother Earth Shrine of King Chimedie (founding ancestor of OgbeOzala), neither Odita nor his Vessel of God (Okwachi) is anywhere to be seen. Since the presence of a virgin girl dressed in white carrying this vessel atop her head has been a prominent feature of all the other Ozo title emergence ceremonies I witnessed, the omission seems noteworthy (especially in light of the fact that Odita’s own daughter is eligible to play this role). Obiekwe Aniweta, wearing his red Agbada, leans against a wall and comments pointedly on the absence of this symbol, and I sense he is keeping some kind of account of every stage of the proceedings.

I am later told that Odita did participate at one point in the subsequent celebratory dancing, but it must have been a very brief appearance since I never saw him. In contrast, his new wife plays a very prominent role, and her age-grade participates actively while Odita’s own age-grade does not dance in procession to this scene to salute him, as might well have been expected. I leave late in the evening, feeling that this Ozo Title ritual has been unusually vague in quality despite the exuberance of some of the participants.

That night, however, Byron Maduegbuna dismisses my questioning description of Odita’s public ceremony, saying that the details of the ritual sequence are not really very important. In his opinion, this event has now reduced the number of serious kingship candidates to two: Moses Odita of Ogbeozala and Moses Emembolu of Isiokwe. But realistically, he says, in light of this new Ozo man’s far-superior education and public prominence, Byron’s people will probably now give way, and he anticipates a situation where the Royal Clan Conference will now probably select Moses Odita unanimously. The Nigerian Spokesman of June 19 reports the event under a strong headline:

CATHOLIC LEADER TAKES “OZO” TITLE: NO CHURCH BLESSING:

HISTORY MADE.

Commenting that although there was anxiety when thick clouds gathered “as though it was going to rain,”21 the reporter added that the sky brightened for Odita’s Egwu Ozo dance as the performance began:

“Although the new member did not do the traditional dancing himself, Mr. Odita who was clad in white native suit ‘TOS Benson in London’ and wearing an eagle feathered cap at a certain stage, jumped into the circle and danced to the tune of the traditional drum amidst cheers, and shouting of his title name ‘Ozo Obi Akazua.'”22

“Asked whether his initiation received his church blessing, Ogbuefi (Cow- Killer) Odita said: ‘I wouldn’t say that.

‘All I know, I have not contravened any law of the church through my initiation ceremony.’

He also denied any suggestion that he took the title under some condition dictated to him by the church.

Observers over the week end however, described the initiation as epoch making in the annals of church history in Onitsha.”

6. Devout Christian commits Pagan “Sin”

The final serious ritual test through which an Ozo title aspirant must traditionally pass is the “Reckoning of Ozo Accounts” (Igba Ugwu Ozo), in which the men of the candidate’s Ozo group (in Odita’s case, those of Umu-EzeAroli) assemble with him to criticize his performance and levy any additional fees or duties deemed necessary. According to my informants, on Saturday, June 17, The three Senior Lineage Priests of Umu-EzeAroli (the heads, respectively, of OgbeOzala, of Umu-Omozele, and of Agadagba segment of Umu-Aroli sit on the throne together presiding over this ritual with the representatives of Odili family (Odita’s immediate lineage segment within Umu-Odiali) when one of the priests, Ononenyi Emejulu of Obi Omozele segment, is accused of having accompanied Moses Odita to St. Mary’s Roman Catholic Church prior to the Ozo emergence ceremony, where Odita (it is alleged) took his Ozo Title Staves (Ossissi) to be blessed by Reverend Father Obelagu.

Ononenyi Emejulu at first denies the accusation, but when asked to confirm the denial with an oath on his ancestral ghosts, refuses to do so and then confesses that he went by night in a car to the church, where the Ozo Staves were (1) marked with the figure of a cross, and (2) blessed with Holy Water by Father Obelagu. This means that the Surrogate Ozo man who was presented before the Mother Earth Shrine of King Chimedie had come there wielding contaminated Staves. The Ozo men of Umu-EzeAroli now refuse (despite impassioned pleas by those close to Odita’s lineage) to complete the conferral of his Ozo title, and insist that new Ozo Staves be prepared at once.

According to people close to Odita, this was quickly done, but when it is pointed out that, furthermore the Okwachi which should have been carried by Odita’s daughter did not appear at the ceremony, and that the sacred Eagle Feather (Ugo) had also been taken to the Church for blessing, the Umu-EzeAroli Ozo men refused to continue the ritual.

Odita’s agents appeal to the Onya as Head of Umu-EzeAroli, but the Fourth Minister (together with most Ozo men of Umu-EzeAroli) decide that the whole performance has definitely been an insult to Ozo titled men of Onitsha, and so the matter is placed before the Onitsha Chiefs (Ndichie).

On Sunday morning, when the Reverand Monsignor Obelagu gives Moses Odita Holy Communion at Mass, hisses and voiced comments are heard from some in the congregation. Some members walk out as Father Obelagu openly proclaims in his sermon that Odita brought his Staves to the Church for blessing and that other Catholic Christians who aspired to the title should emulate his example. (Saying this shows that Church officials knew their cover had been blown away.)

These startling developments are reported in front page headlines in both the Spokesman and the Observer on June 19 & 20. The Spokesman supplements its account of the events with an editorial suggesting that Odita “has stabbed Onitsha almost fatally from behind,” while the Observer (quoting Obiekwe Aniweta as its source) reports an element which has been spoken privately but did not appear in the Spokesman account: an allegation that “the wrong person handled the Osisi [title Staves] for Mr. Odita.” In private conversations I learn that this latter action is considered by many to be the most grievous of the several offences committed, in the eyes of many Ndi-Onicha: someone in St. Mary’s Church who handled the Title Staves (and other objects) is said to have an abominably blemished genealogy. Such a person, several Onitsha traditionalists asserted, should never be allowed to touch any Ozo symbols, regardless of any relationship he might have with the Christian religion.

On June 22 and 25, the case is heard in the house of the Onowu, first before the Chiefs and then before all the Ozo men and other elders of Onitsha. At the meeting of the Chiefs, men of Odili lineage (Odita’s own branch of Ogbeozala) speak for Odita. They insist and are able to demonstrate that there are numerous precedents for de facto association between traditional Onitsha and Roman Catholic symbols, but the Chiefs respond that the contamination of the Staves reaches deeper than that: the fact is that a “wrong person” has handled the Staves. At the plenary meeting, Odita for the first time decides to defend himself, and denies that he took his Ozo Staves to the Church for blessing. He admits that he carried them in his car when going to St. Mary’s for Confession, but denies removing them from the car.

Barrister Luke Emejulu (now himself an Ozo man and a strong supporter of Enwezor) then rises to express surprise that Odita now denies these acts when at the previous meeting no question was raised about the facts of the case. The Senior Priest of King Chimedie family then calls on his throne-seated colleague, Ononenyi Emejulu (who is Luke’s immediate Senior Lineage Priest), to confirm his earlier statement about the trip to Saint Mary’s, but Emejulu now denies ever having said he made such a journey.23

After consultation among the Chiefs and Ozo men at this meeting,

“the Onowu of Onitsha, Chief Philip Anatogu, traditional Prime Minister and Regent, announced to an anxious audience that henceforth any “Ozo” title taken by person who before or after the initiation takes his “Ozo” emblem (“Osisi,” “Ugo,” “Okwachi,” et cetera) to the church for blessing will be nullified no matter if the person offers millions of pounds.”

The Prime Minister then ordered Odita to perform the following ritual acts:

“(1) That he should first destroy the church blessed ‘Osisi‘ and bury it because it has been desecrated by the church processes it was subjected to.

(2) That he should get the people of Nri, three members of the family, provide one ram, one cock and one young chicken to perform the propitiation ceremony of ‘Ikpu Alu’ (clearing of an abomination) as the church blessing of ‘Osisi‘ is regarded, and in performing the ceremony, they should pass through all parts of Onitsha,

(3) That after that and not before should a new ‘Osisi’ be made for him.

According to custom he should pay a certain sum of money to the people of Onitsha for reconciliation, and this was assessed at 10 pounds sterling.”

On June 27, the Spokesman prints an Editorial entitled “Historic Decision on ‘Ozo‘ Title,” which refers to Archbishop Heerey’s putative involvement in case as a “slap on the face of the people of Onitsha,” and concludes that

“While it was the desire of the Head of the church among us to remodel ‘Ozo’ so as not to make Catholic adherents feel below or ostracised in the society in which they live because they do not join the ‘Ozo’ society, the people of Onitsha felt that tradition was one thing and the church quite another.

Perhaps it will be a lesson to all those who underrate the stand of Onitsha people in the preservation of their tradition.

Perhaps it will be realized now that any modification ought to come from the people themselves after due consideration and should not be dictated or imposed on them.”

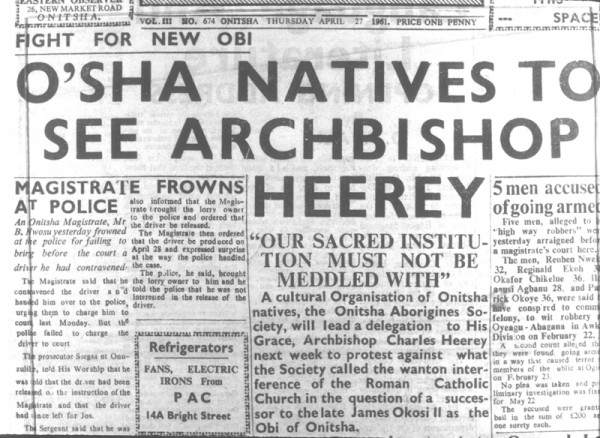

7. Performing Ikpu-Alu