In the fall of 1960, when we begin our Onitsha research phase working with Byron Maduegbuna of Isiokwe Village in Onitsha, he often surprises me with a suggestion that we travel to some hinterland Igbo community in order to witness some kind of event. (I think sometimes he had business in these locations, and knowing that our Fiat vehicle (motu-machis) was available, he could thus gain transportation with less bother than he would have to face when negotiating with the grasping touts who worked the Onitsha Lorry Park. Many other conveniences would result from having transportation at his destination also.

But this is idle speculation: The fact was that he was very alert to the affairs of the region, he knew where my interests lay, and he was interested in a wide range of social and cultural activities himself. We in fact enjoyed each other’s company and interests.

Note: Click on any image you want to enlarge.

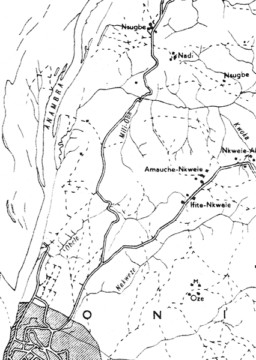

On this occasion — the day of the outing of a grand Ijele masquerade, organized for the people of Nsugbe by their new Igwe or Obi — we drive from Onitsha on a dirt road, shown on the map at left. The three named places shown along the northern end of the map are all parts of this town. We first traverse the uplands directly north of Onitsha, from which we view, below, the lower foothills dropping down toward the Anambra River and Mamu River basins. At far left-center a portion of the Akpaka Forest Reserve(north of Onitsha) is visible.

In the view above, you can see how the land drops into that part of the Igbo country called “Olu” — the Riverine Lowlands. The Anambra River is visible in the remote distance. Nsugbe spreads out from the Anambra River’s edge into the low hills visible at mid-right in the photograph. 1 The closer view here at right shows the crowded traffic (mainly pedestrian) heading toward Nsugbe, a portion of which is visible beyond the trees in this image.

As we approach the town along this road, the traffic becomes much denser, and we stop briefly to observe the crowd. A few lorries are moving among the many pedestrians, nearly all market women and their children, but a passenger automobile suddenly comes rushing through, its hired driver , accelerating with a jerk, then braking abruptly, endangering pedestrians as he honks his horn and pushes past them. 2

Byron’s Target “Family”

Arriving at our destination, our first stop is the home of Byron’s personal steward, the young man at rear–right in the group photo at left, who at the family’s insistence poses here with Byron and members of his Nsugbe family. 3 The man at left, the steward’s father, excuses himself upon our arrival and reappears for the photograph wearing the costume you see here, regarding which Byron jokes to me about the “most curious garb”. It was a very colorful array including what I would call pajama pants — unfortunately I was working with black-and-white film. The man wearing the feathers in his cap is a senior, titled family member, clearly an Ozo man judging by the feathers and the elephant-ivory horn perched beside him to his rigfht. The form of his cap , and his ivory bracelets, are distinctive features of an Nsugbe man’s title apparel in the early 1960s.

Meeting the New Obi

Then Byron takes us to meet the Igwe, the “Obi ” of Nsugbe. I put this title in quotation marks because — as I later learn — this is a new title for Nsugbe, elaborated in light of the newly established “House of Chiefs” established in the governement of the Eastern Region of Nigeria. 4

(For this meeting I have meager personal memory and no photographic record at all. I become somewhat bewildered by the entire situation, but Byron provides very little context, though he informs me that the celebration we are attending entails the Obi‘s presentation of the Ijele Masquerade to the people of Nsugbe. After I have been introduced to him in a cursory manner, he offers me a drink of English tea, and we sit quietly together for a few moments. I must experience utter confusion, since I record nothing of our talk, and later remember nothing of what he says (which is very little), and I am nearly speechless.

I do manage to observe that he is of lighter facial color than most Africans I have been meeting, and he has wavy black hair. (Helen had not joined us for this trip, I am not sure why. Had she been present, no doubt better and more informative conversation would have emerged.) Byron tells me afterward that the man is in fact an Isiokwe native (i.e., Onye-Onicha), but this is not a subject to be discussed at this point. (Okunwa T.B. Akpom later told me that his name was Anyansi and that he indeed was originally a member of Byron’s village of Isiokwe in Onitsha.)

The Public Arena

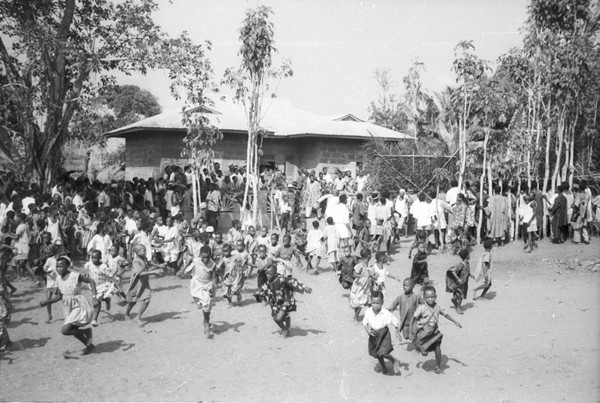

Byron and I then walk to the public square (Ilo) of Nsugbe, below, where a substantial crowd has gathered and a group of children are dancing,. To the rear at far right, the masquerade is contained within its construction fence, officially still invisible as a “place of creation”.

The chamber of creation is concealed by a high fence of bamboo interwoven with sticks and various protective medicines (ogwu).. Groups of men however dare to gaze into the chamber, which is flanked by a large grove of banana trees (symbolic of childbirth).

Children, both female and male, dance in the village square (ilo), wearing their best clothing

The Appearance of Nne-Mmanwu (“Mother of masquerade”)

Then, while a group of village women dance behind her at left,, the Mother-of-Masquerade (Nne-mmanwu) strides forth, making her own remarkable dancing signatures: brandishing her long, slender staff, she repeatedly casts its tip out on the ground in a dramatic, abrupt zig-zag way, leaving long, jagged dark marks running left-to right on the ground with each statement. I ask Byron what these actions might signify, and he says, “she is showing that her Igwe has the power to write”.

[Editor’s note: Over the years since observing this moment, I have thought of the Book of Daniel — “the Writing on the Wall.” Here the writing appears not on a wall but on the ground, the “mother earth” (ani, as the Onitsha Igbo say it). Some Onitsha and other igbo-speaking women are thought to have powers of prophecy, and in this moment this woman was performing a remarkably prophetic act, saying “Writing is Power”.

In closer view, Nne-manwu displays some striking features. Her headdress appears to be classical Igbo women’s style. Compare two Onitsha women 1960 : Her face is covered with white clay, her nose has a slightly Roman cast, and her neck presents what appears to be a complex gorget-like material around the front. Her left arm has what appears to be an ivory bracelet, while her right shows a design pattern around the elbow, and a pale-colored horsetail fly-whisk dangles from the wrist. The skirt portion of her dress forms a multi-colored-and-patterned array of strips, reminiscent of the strips of dangling cloth that mark the skirt of the Ijele (see further below). She appears to be barefoot (or perhapswears fine sandals). Balanced designs apparently similar to the elbows appear also on her lower calves.

The female dancers behind her at left are dancing in synchrony but do not seem to wear uniform costumes. Note the interesting figure, possibly male, visible toward the left of the dancing group.

Ijele Emerges

Now, at image left, the Ijele emerges, guided by the Masquerade Elders directing it from their stances in the center of the Ilo. At right, the mighty figure stands to greet the core of its crowd. Here you can see clearly the strips of cloth that cover the (hidden) body of this great figure (alluded to in the dress of Nne-Mmanwu, above).

Below you see a closeup view of this mighty action-figure, now standing and walking amidst all the assembled members of Nsugbe community.

It would take us far afield to provide here a detailed discussion of the symbolic, indeed profoundly religious meanings of this figure, a super-human being but one known informally to be human-self-propelling. Here I just say that this Ijele represents the full ideal community of Nsugbe in the context of all its cosmic involvements: above, the sun and the sky, below, the earth and its fertile creativity, and in its mound-and-tree creatures that inhabit it: at the base (and the head-dress-waring figure below it, well-clothed), the fertile earth is guarded by a primary protector, the encircling python. Out of the earth emerges a great, burgeoning termite hill, its amazingly fecund residents communicating with ancestors in the earth below; out of the termite hill emerges the great tree which provides food and residence for all its creatures. The community is shown to be vital, thriving, and beautiful. (It is also somewhat terrifying in its scale — it rises so high (suggesting rainbows), and displays complexity; it moves, it is alive, dynamic.

For full details on the meanings of Ijele, see

Henderson, Richard and Ifekandu Umunna, 1988, African Arts vol. XXI, no. 2, pp 28-37 (with many images): “Leadership Symbolism in Onitsha Igbo Crowns and Ijele”. (Available as a .pdf through Jstor inn University libraries)

Some Further Comparisonns in Time and Space

The Ijele figure occurs in many Igbo communities, and certain features recur, but each one is also unique. Here I will simply note a few major features.

In these parts of Igboland, respect for figures high in authority is often translated into a much more ancient power figure: an armed person riding a horse as we see at left, (this one atop our current Ijele looks like a Euaropean-colonial officer and carries a rifle on his back). That this specific ritual symbolism is ancient among the earliest representatives of Igbo-speaking Kingship is shown by the bronze figure at right,from one of the Nri-linked Igbo-Ukwu archaeological sites located southeast from Nsugbe and dating to around 800-900 A.D. 5 The pattern of facial scarring in this horse-riding figure makes the Igbo connection indisputable.) In the Nsugbe horse-rider at left, the fact that ascendant power-holder is clearly a European personality; reflects the fact that — although 1960 was a time of incipient Nigerian Independence — Igbo-speakers generally gave these colonial figures their due while they remained in official power. Note, however, that standing strong behind the British overlord figure in the image at left is a large, black statue of the Vulture (Agwu), a spirit-being of great power and one transcending time. It’s no accident that this profoundly respected figure is located near the top of this micro-cosmos (and of course, vultures are creatures “of the sky”, they fly far above our earth-bound heads).

A Glance Ahead (and Beyond)

the disastrous Nigeria-Biafra Civil War ended in 1969, the Onitsha native Ukpabi Asika was appointed to act as the Nigerian Federal Administrator of the newly-designated East Central State, charged with guiding the re-integration of Igboland into Nigeria. During this time he witnessed in 1970 a new Emergence of an Ijele in the town of Awkuzu (shown at left here). (Mr. Asika — who later became the Ajie Onicha, a senior title there– stands at left foreground in this image, a copy of which he generously sent me by mail.) At above right, you can see the elevated figure at the top of the complex. Like the Nsugbe Colonia-eral figure, the master in 1970 still wears what appears to be a pith-helmet, but his face is clearly black. (Note also the greater elaboration of the “Mighty Tree” motif presented in this version, with its leafy branches very prominently displayed.)

Presenting views of European rulers as figures located “on high” in religious symbols of Igbo community appeared in many parts of Igboland during the Colonial era, for example in some of the famous “Mbari houses” found in areas southeast of Onitsha — see Herbert Cole’s brilliant accounts of these massive, termite-mound-based symbolic structures, dedicated primarily to the Mother Earth.6 At above left, a small one I photographed in 1961; you can see here the typically stepped-conical form of the mound (protected by iron roofing), and at right , beneath the roof of a larger one I found nearby, you could see its upper tiers displaying an array of obviously European colonial officers looking out and down from windows near the top. Note the secretary at the far right, writing industriously at his desk. (Writing was very strongly emphasized as a symbol of colonial power). I guessed this Mbari house had been created at least a couple decades before I arrived to witness its gradual rotting back in the direction of earth-ruin.7

Returning our focus to the Nsugbe Ijele, a closer view of the central structure reveals at left a large central trunk rising out of the rather conical-shaped mound standing on the base. The view of the midsection is complex — many creatures may be seen perching at various branching levels — but a central feature of the base is the image of the python (agwu-ola), a major figure in igbo religion.

Finally, after Ijele has toured the town, and returns to the home base, a culminating public event occurs: the people e dance out again, and in this moment another figure leads:

The Ijele itself is immortal, the Ancestral-Community-Cosmos incarnate, but everyone of the age of sense knows that only a very mighty and fully dedicated human being can bear the masses (and problems of balance) contained in this enormous construction, not simply lifting it but dancing with it on his head around a large circular passage of the town. Should he fail in the task, this would be a frightful omen for the people of Nsugbe, and the administers of Agwu (the prophesying powers represented by a vulture) would be hard-pressed to divine what troubles loom immediately ahead for them as a consequence. But this Ijele has succeeded, gloriously, and accordingly, the bearer (still wearing his protective headdress but now seen in his full humanity and wearing a white t-shirt), leads the procession in its culminating dance around (and in celebration of) Nsugbe town.

Nne-Mmanwu’s Genealogical Connections Uncovered —

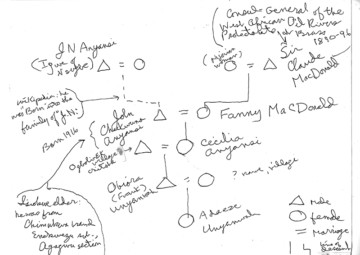

In late 2018, I received an email message from Adaeze Uyahnwah, a native Onitsha woman from Ogboli-Eke village who was searching for information and images regarding her great-grandfather, John Chukwuma Anyansi, who she knew was in the past the Igwe of Nsugbe. She said she was searching for images of him, and of his wife, Fanny MacDonald, who she said was her great grandmother, and “the daughter of a Nigerian woman and a British soldier who acted as consult general to Nigeria in the late 1800’s.” These connections had aroused her interest in this webpage, and she wondered if I had images of them.

This led me into further research, with her and with the Obi of Onicha and with members of Isiokwe family of Onicha (which, as I reported at the outset, Byron had said was the original family of Igwe Anyansi. On the basis of my subsequent communications and a brief scanning of Wikipedia, I present the following (incomplete but I believe accurate) genealogy of the people remembered, together with images of two of the main characters:

Sir Claude, above center, served an extensive and prominent career in the British Military, including his tour as “consul-general at Brass in the Oil Rivers Protectorate” (“Nigeria” did not exist until 1914) between 1889 and 1896, when he retired from Service.8

Regarding the person shown above left, I strongly suspect that she was (in at least one of her names) Fanny MacDonald.

Of course, remembered genealogical links are unproven as such without genetic testing and comparison. But in my view this evidence adds an interesting new dimension. Both Sir Claude and John Anyansi have biographical entries in Wikepedia. My hope is that from John’s we can obtain a photograph of John Anyansi that will compensate for my failure to capture one when I met him so briefly in 1960. Obi Achebe of Onitsha remembers him in some detail. Anyansi attended Obi Achebe’s first ofala celebration in 2002, and later communicated with him regarding it, but no photo was obtained.)

- It is classed among Indi-igbo as “olu” or “adagbe“. [↩]

- I neglected to photograph this scene, but was quite alarmed for the safety of bystanders. In 1960 , any person of means was expected not to drive his own vehicle, but to hire a servant for this purpose. Many of these hired drivers were grossly ill-trained, and seemed to regard their social roles as direct expressions of personal power. [↩]

- Byron may have some business to do with them. [↩]

- Onitsha people are acting as instruments for spreading the “ObiI” tittle among people who have previously lacked it. [↩]

- Shaw, 1970, Volume II, Plates 365 & 366. In this volume, see Chapter 2, the page on “Niger-Benue Worlds…Nri. [↩]

- Cole 1969a and 1969b. [↩]

- As Cole observed in his essays, once these massive communal creations had been built and presented to the community at large, they could never be repaired, but were left to erode slowly into the clay from which they had come. [↩]

- This information and the associated image comes from his Wikipedia page. [↩]