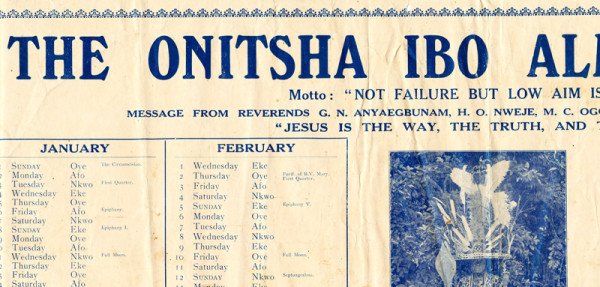

Above: a fragment of “The Onitsha Ibo Almanack 1933”, wall-poster Icon of the Inchoate Home Branch of the Onitsha Improvement Union. Its Motto: “Not Failure But Low Aim is Crime”.

[Note: Click on any image you may want to enlarge.]

Ndi-Onicha received increasing pressures regarding “modernity” early in the 20th Century, coming from their fellow “natives” living “abroad” (primarily in Lagos, the main birthplace for Nigerian nationalist politics). Efforts to establish an “Onitsha Friendly Society” began there as early as 1918, to be repeated with greater success in 1926.1

These early associations aimed to enhance cooperation among Lagos residents whose permanent homes are located in what is at the time Onitsha Division, and as such these experiments in group-formation initially included men who were non- Ndi-Onicha, for example educated Africans from Yorubaland or the Gold Coast who had long resided in Onitsha, and educated men who were natives of various Igbo-speaking communities in the hinterlands of Onitsha as well. But when Nnamdi Azikiwe returned to Nigeria in 1934, already speaking out as a harbinger of African Freedom from Colonialism, the political perspectives of all literate Nigerians changed.

When a Home Branch of the “Onitsha Improvement Union” was formed in Onitsha Township in 1935 (the Lagos community having already established an OIU in that city), educated Nigerians everywhere were discussing prospects of eventual self-government.

1. “Certificate of Membership” Insignia

The formative processes of this Home Branch are reflected in its earliest 1935 Minutes . After initial reference to a previous meeting for which apparently no record was kept, the minutes of March 8 show the prospective members focusing their attention on concepts and images which might convey the meaning they intend for membership in the Union. After a brief debate it is agreed that admission to membership would entail a “firm declaration” to the effect that

“I the undersigned do hereby affirm after having read to my understanding and satisfaction the regulations and bye laws governing the society, that I will be a member of Onitsha Improvement Union, Onitsha, and will ever be faithful, loyal and obedient to the said regulations, bye laws and all manner of orders issued in connection with the union’s affairs. So help me God.”

The declaration is noteworthy for its emphasis on literacy and British legalism, while its emphasis on loyalty and obedience to orders outlines a rather military oath of allegiance.

Once the declaration had been signed, proof of the individual’s membership would then be formally embodied in a “certificate” stating the date of his admission and signed by the President (and “three or four other signatories to be decided by the meeting”). Developing a suitable form for the certificate — one providing a formal visual and written symbolism expressing the meaning of Union membership for the individual concerned — then became an issue which would occupy the members’ interests for several months.

At the July 3 meeting the President and Secretary presented their design for “the certificate to be printed for the Union.” In response to a member’s request for the meaning of the traditional Onitsha ceremonial sword (Abani) and spear staff (Ogbanchi) represented as a crossed pair on the design2,

“The president explained that the two imply the well known maxim Igbo Enweze (the short form of Igbo enwegh eze, “The Igbo have no King”). The secretary supplemented this by saying that the two are emblems of authority originally the ndichie (Chiefs) were warriors of the king…. In view of their position they hold Ogbanchi or Abani as their insignia of office in order to distinguish them from the commoners or the plebs. It was agreed that members should dive to know further possible explanations of the two objects.”

The proverb stated here by OIU President P.H. Okolo connects the insignia to the most salient traditional cultural distinction contrasting Ndi-Onicha and the Ndi-Igbo who were now almost surrounding them in the city. Secretary M.O. Ibeziako‘s supplementary explanation emphasizes the social inequality associated with this distinctiveness, the presence in the Onitsha indigenous community of an elite circle of superior authority holders (underlined here by the contrasting reference to “plebs”).

While the words reported as those of P.H. Okolo and may well have been his own, Secretary M. Ogo Ibeziako was an administrative clerk in the Onitsha Resident’s Office, and had therefore gained active participation in anthropological research undertaken by C.K. Meek, subsequently published in his Law and Authority in a Nigerian Tribe (1937), a volume used by colonial officials in their efforts to redesign their system of governing in Igboland.

This is not the place to expand on Mr. Ibeziako’s various and often important roles in the history of Onitsha communities, but for more details on his career see this link: Onoli M. Ogo Ibeziako.

The new President, his Secretary, and several other members of the Onitsha Improvement Union obviously shared a close (and for some career-salient) interest in relationships between Traditional and Modernizing activities.

The significance of the crossed sword and staff insignia was further discussed on August 7, when members reported various details about these two instruments of chieftaincy, all reflecting a single dimension of significance. The Secretary recounted that

“In these days of old the only goal (sic., “means” is intended, RNH) to gain any honour was through championship in war. Men aspired to obtain enemy’s head in order to be decorated with eagle’s feathers and be awarded the appelation of Ndi-Ogbu (‘Killers’). Such conquerors besides had to parade the town and (people) sang the praises of their bravery. They were applauded with initiations and rituals, and as promotion occurred they take the much coveted title of ndichie (chieftaincy). This title has as its insignia of office a spear (Ogbanchi) and a sword (Abani). With them they swore allegiance to the King.”

At the same meeting, two members began to press for a committee to be formed in order to gather more information on the subject of these two traditional emblems to be displayed on the certificates, but the minutes record that

“The president saw no reason of further anthropological research… the primary objective in going into the matter was to secure a uniformity of meaning of the general symbols of Ogbanchi and Abani. So far this has been achieved. If the union would wish to embark upon further ethnographical issues that would be a different matter. So far Ogbanchi and abani are emblems of war; the union is not going to busy itself in further details the matter is closed at that.”

Setting aside what seems to me the remarkably articulate sophistication of this passage (in 1935, a time when comparable discourse vocabulary in English was rare in most parts of the world), these icons focus the achievement of leadership primarily on means of killing human beings, and link the associated insignia to a connection of such action to positions in a hierarchy of authority. Taken together, the two statements imply both an emphasis on the Union’s need to recognize and understand the bases of existing Onitsha chieftaincy/kingship, and an assert that these institutions symbolize the members’ difference from the “Ndi-Igbo” as Ndi-Onicha, defined as those accustomed to superiority and to operating in positions of superordinate (and subordinate) authority. The legitimacy of this authority is pegged to killing.

Subsequently, members proposed various complications of form for this apparently simple visual emblem of the Certificate of Membership.((While the minutes nowhere contained a sketch. I did see some examples of an Onitsha emblem of this kind on various documents encountered elsewhere, some of which added a confronting leopard’s face placed above these symbolic weapons, the leopard representing the “king” (Eze) of the bush (Afia), that is, the top predator of the encompassing wilderness.))

Overall the minutes are sketchy on these elaborations, but immediately after the President’s authoritative closure of the sword/staff discussion, they register the following:

“Mr. Odogwu suggested an inclusion of the Union Jack to appeal to outsiders mostly European that in all our endeavours we appreciate British Justice Fairplay and equity which the Union Jack symbolizes. This suggestion met with unqualified endorsement of the meeting.”

Thus the members emphasized that the Union’s identity as expressed in the militantly oppositional emblems of crossed staff and sword was not directed against the Colonial Presence. On the contrary, certain specified British values and principles are claimed to comprise an important supportive context for the group’s activities.

On August 21 a draft of the certificate design was again circulated to the members, and thereupon “Mr. Onwuatu opposed the presence of the coat sleeve etc. on the two hands shakes in the design. He held that in as much as the Union was for things African the coat sleeves suggested Western Ideas.” This gave rise to an extended controversy which

“gave birth to three schools of thought one advocating the deletion of the coatsleeve the other that a substitute of two drawings of Africans (this word has been crossed out) natives hanging loose cloth in shaking hands would depict better the true position the third say no reason for any departure from the existing designs.

“On the motion of Mr. Mbanefo that the design was in order and nothing further should be added to or deleted from it, Mr. Onwuatu moved the following amendment: that the coat and shirt sleeves on the hands of the design should be removed so that only the bare hands could be seen.

“The amendment was put to vote the result was that 6 voted for and 10 against consequently the amendment was lost the motion was unanimously carried.”

While this voting registers the presence of a significant opposition to the coat sleeves, it is clear that European dress was a strongly-supported aesthetic standard for the group. At the April 3 meeting where the taking of a group photograph of all foundation members was unanimously voted “as a token of remembrance of inauguration of this society”, a directive followed: “Members to appear in uniform, namely black and white with collar and ties of course.”

Even more interesting is the evidence of an apparent conflict concerning the appropriate discourse of self reference, and its ostensible resolution (“natives” is deemed more appropriate than “Africans”). Relevant contexts of this issue include not only the immediate prospects of local government change but more broadly the newly-emergent pan African movement. In 1935 Nnamdi Azikiwe was currently writing from Accra, emphasizing (as he would soon broadcast internationally through his compelling book3, the rise of “renascent Africans” who were attaining such identity transformations as “mental emancipation” and “national risorgimento”. Employing the term “African” was politically controversial in contemporary Nigerian social contexts wherever Europeans were present (or might otherwise learn of such talk). From this perspective, use of “native” conveniently avoids such controversy. (It was important at this point to avoid alienating the British Authorities.)

However, this choice may well have arisen less from a “colonial mentality” on the part of the discussants than from a desire to emphasize in their discourse that the hands shaking were those of Onitsha indigenes rather than of any broader social category. As the symbolism of the Membership Certificate implied in its crossed royal sword and spear symbol, this Union excluded non-Onitsha indigenes (and specifically Ndi-Igbo) from its membership. While the early minutes suggest some degree of openness on this point, membership rolls indicate strong closure on these narrow ethnic grounds.

2. European life styles in the context of Kingship

That capacity to operate in European circles was very important seems clear from the fact that even Onitsha indigenes who lacked the credentials underpinning an appropriate “collar and tie” life style were marginalized or excluded by means of various social pressures (for examples, see further below). “Colonial mentality” is of course today a pejorative term in social science discourse, but the term skews into presumed attitudes what may as well be described as a behavioral strategy that makes sense when a societal context of overwhelming Colonial Government power is acknowledged. Using the more neutral term “accommodation”, the question arises: To what contextual conflicts does this constitute a response?

One striking feature of the Home OIU minute books for 1935 is an almost total absence of any overt specific reference to the contemporary politics of Onitsha town, beyond the abstract and apparently academic references to the significance of the Onitsha King and his chiefs described above.4. This is remarkable in light of the fact that from 1931 through 1935 Ndi-Onicha were living without an Obi, in a fluid process of complex and bitter factional competition while “the King is Sought but Not Seen”. In this condition the Onitsha community had become even more disorganized than it had been during the reign of the previous, broadly unpopular (and now deceased) Obi Samuel Okosi, and eventually the Colonial Government began holding numerous meetings of the community seeking to stimulate resolution of the conflict, while persistently refusing to intervene. By mid-1935 no solution was in sight, and yet the Home Union minute books remain silent on this subject, in marked contrast to their strong concern with the symbols of chieftaincy and kingship in the abstract. This suggests the presence of an unwritten rule barring such attempts by the group to “eat ants” (one trenchant metaphor indicating such controversy).

No doubt a number of good reasons were relevant to this silence, including the task of building internal solidarity in the new organization despite the fact that its various members probably supported different candidates for the throne. Beyond this, the fact that many members had in some measure deliberately distanced themselves from affiliation with “native culture” seems certain: some OIU leaders, for example, repeatedly slighted these meetings in favor of attending Christian retreats and confessions (including the President). Though religion is not strongly emphasized in these minue books, an orthodox (Catholic or Anglican) Christian version of “modernity” is implied in many of their discussions.

But more salient were the plans the colonial regime was now openly developing for governing Onitsha township. By 1932 the Government was reorganizing the whole of (what was then) Onitsha Province in light of the newly systematic policy of Indirect Rule, changing local administrative and judicial systems away from more or less direct and continuous domination by European officials (and some of their casually-selected lackies) and toward allocating greater measures of power to more carefully selected “Native Authorities” (those whose tenure and roles would be based on current anthropological research into “native law and custom”).

But (as the Resident of Onitsha Province put it in 1935) while “the less forward areas” of the Province had already been reorganized along those lines, “Onitsha the Headquarters of the Province and probably the most important unit therein… could do nothing in the part of progress”, because Ndi-Onicha were proving themselves unable to autonomously select their new Obi.((O’Connor (1936 37):paragraph 34. That Onitsha was the expected leader of “progress” is reflected in a remark contained in the 1936 Annual Report for the Southern Provinces, where the writer says “what Onitsha thinks today, the rest of Ibo thinks tomorrow.”))

Since the new Secretary of the OIU, M. Ogo Ibeziako, was Chief Typist in the Resident’s Office, and another of its members was an Interpreter for the District Officer, the men who formed the Union were well informed of these plans for local government reform being discussed by Government as they developed during the 1931-35 Interregnum, and by 1935 the members of the OIU knew that reorganization of Onitsha town would establish an Onitsha Native Authority (ONA) that would include both the Obi and his Chiefs in a Council (which meant that some 39 Onitsha chieftaincy titles, many of which were then vacant, might well become eligible to draw salaries), that both Native Court and Township (with their revenues) would soon be under control of this Obi in Council, and that later on “non-chiefs”, that is to say educated people, selected eventually through some kind of “democratic” process, would probably be included in a broader “Onitsha Town Council” which would then proceed to manage the entire Township.

All of the behaviors of the OIU just described must be read in that light, in fact on the same occasion (November 8, 1935) when the Acting Resident of Onitsha Province presented Government’s decision to recognize James Okosi (a literate son of the much-maligned Obi Samuel) as the new Obi, he also reported the Governor’s approval of the first of these political changes.((O’Connor (1936 7): paragraphs 39 43, 46.))

The Union’s focus on the symbols of Kingship and Chieftaincy was thus very timely, as was its linkage with the reference to the Others (particularly ndi-Igbo) populating the city in rising numbers, some of whom were beginning to voice interests in its governance and who thus comprised prospective competitors for power. The salience of “Union Jack” lifestyles and values becomes obvious in view of the fact that British Government officials would soon be screening prospective local “non traditional” leaders to occupy “Indirect Rule” positions, and presumably looking for those who would be supportive of their own world-views.

3. The OIU confronts the “Age Grades”

In September of 1935, the minutes record what may have been the OIU’s first Ndi-Onicha public action, a message directed to the Chiefs “with regard to the improvement of the Onitsha Inland Town Road,” but it recorded that “the chiefs were divided in their views and so did not make any move.” Although the meeting of 6 November (2 days before the Official announcement of Government’s selection of the new Obi) made no mentions of the Obiship, a special meeting on November 27 now openly discussed this, recording a list of expenditures made in connection with Obi James Okosi’s forthocming accession. Telegrams had been sent to the various union branches: “Obi coronation ceremony 23rd instant under auspices Improvement Unions soliciting your financial support bank urgently. (Secy)”, and the sum of £15 had been collected from the various branches and was spent by the Home Branch on the new Obi‘s first public Festival (Ofala). On January 9, 1936, Secretary Ibeziako was publicly thanked for his work on the accession Festival, and the minutes record that the new Obi was negotiating with the union for “a new dress” for him to wear in a group photograph to be taken together with members of the Union.

These passages mark the beginning of a sustained effort by the leaders of what they now called the Mother Union to build new connections between itself and the traditional leadership of the Inland Town. In April 1936 the Obi accepted the Union’s request that he become its Patron, and the Secretary said an interview had been arranged to discuss with the new King the “proposed amalgamation” of the Union with “the other functioning age grade association.” This proposal (which later minutes indicate was suggested by the Obi) was addressed by several OIU speakers, who agreed to oppose it on the grounds that

“1) The IU is already a central organization containing representatives of all age grades now functioning. Such representatives could always take the interests of their respective age grade when occasion demands it.

“2) The consolidated age grades or their representatives could not be emerged (sic) with the improvement union at the expense of confusion and dissolution of the federation.

“A committee was deputised to interview the Obi.

“One member was accused of divulging meeting matters at the meeting held at the Obi’s palace by P. Egbuna, concerning amalgamation.”

Later minutes (and supplemental data connected with the 1931-35 Obiship dispute) help to clarify these points. On May 6 it was noted that P. Egbuna had called a mass meeting in the Obi‘s Palace to propose his stated scheme for amalgamation of the OIU with the Age grades; in the May 27 meeting, Peter Egbuna’s membership in the union was debated, and he was replaced on its Executive Committee by another member. On June 10, 1936, the meeting accepted his letter of resignation from the Union.

Peter Egbuna is an important figure in this context because he, together with another Onitsha man, Peter Achukwu, held reputations (when I was in Onitsha during the early 1960s) as long standing “Orator Spokesmen” (ndi-ekwulu-ora), a social category whose embodiments performed important (and often counter- hierarchical) political roles in the traditional social structure of the Inland Town.5 Both men played significant parts in the effort to resolve the 1931-35 Interregnum conflict by mobilizing the younger levels of the traditional Onitsha age-sets (refered to as “age grades” in the minute books, and in most Onitsha reference works) into an organization that came to be called the “Eight Age grades” (Ogbo isato, sometimes also called the “Seven Age grades”, Ogbo-isa, and which generated something of a local mass movement seeking to resolve that conflict).6. This amalgamated cluster would be classified in anthropological terms as (for tht time) a broad age grade of married “youngmen”, roughly from 30 to almost 50 years old.)) Acting Resident O’Connor referred to this group in his decisive Interregnum Memorandum:

“Early in January 1935, the Ogbo Isato a group of age grades in Onitsha endeavoured to exert influence in bringing the Ndichie and Elders and others of Onitsha to end the disputes.

“This attempt from circles not immediately involved in the election of an Obi was very creditable and instanced the general desire of Onitsha to have an Obi and to end the wrangling of candidates. “One direct result of this was to induce the Administrative Officers to renew their attempts to procure a settlement….

“It was suggested [to one section of competitors] purely as a piece of advice that if they really could not bring about a decision they should adopt the suggestion of the Ogbo Isato and choose the candidate from Umudei [i.e., James Okosi].”

Thus the Eight Age grades took their stand behind the most educated of the candidates, the eventual winner, James Okosi, and thereby presumably gained his gratitude. In early 1936, fresh from this triumph, this amalgamated group was pressing the new King to give them formal recognition in the Inland Town social structure as its prime agency for stimulating efforts to “improve the town”. Part of this effort, reflected here in these Onitsha Improvement Union minute books, was an attempt led by Peter Egbuna (and also Peter Achukwu) to meld the (by then, Seven) Age Grades with the Home Branch of the OIU. [Such a representation (presumably seven sets, each with seven “delegates”) would of course swamp the core OIU members within a very large group.]

The name Peter Achukwu appears in the first meeting recorded for the OIU, merely to say that he should be regarded as a “non- foundation member” (that is, not one of the creating elite). He seems to have been a very marginal member from the outset, and in the sole reference to him thereafter he acts as a spokesman for the Age Grades. At the 1939 Annual General Meeting he was expelled as a “non member”, suggesting that by this time he was viewed as an antagonist.7

As the Union’s involvement with the Obi, his council of chiefs, and the Eight Age Grades becomes more prominent in the early Minute Books, another feature appears: efforts to change the membership criteria of the Union. On March 4, 1936, a member recounted his visit to Port Harcourt, where there were

“some criticisms levelled to the Home Union by the PH members at a private gathering. The major ones were that the Home Union is composed of wealthy class and that the President once refused one Mr. _____ room for admission in the association.”

In June, at the same meeting where Peter Egbuna’s resignation from the Union was accepted, the matter was raised that Mr. Odogwu (the Assistant Secretary and one of the leaders in founding the Home Union) had written the Union an insulting letter. Asked to defend himself, he said that he had submitted his report as before but a previously acceptable level of work was now deemed unsuitable;

“That reminded the Accused of a certain time in the meeting in which he was described as a mere holder of St. VI certificate. The meeting was silent and no enquiry was instituted to such an action which was highly improper.”8

References in a number of meetings during this period suggest that outsiders believed the union was “too exclusive” in its membership, as well as snobbish in discriminating among members. Literacy was clearly a screening criterion, but the comments of Mr. Odogwu indicate that finer distinctions were being drawn concerning relative educational qualifications among the members themselves. Several references suggest that OIU branches abroad were pressuring the group to admit a “wider representation”.

In this context, the movement to associate the Union with the traditional Age Grade system of the Inland Town pressured the leadership to accommodate. At an Emergency Meeting August 6, the President reported “the recent mission between the representative of the Union and the Ekwueme age grade” had been advised by the Obi and Council to “summon a representative meeting of all the functioning organisation (sic) in the Town” to consider their unification. The President suggested

“1. That the Onitsha Improvement Union as a full registered, extensive body not based on age grade should be the central organization.

2. That all age grades from Ekwueme to Ogbo Douglas should have two representatives in the Union.”

After much debate it was unanimously carried that the members should go to the Obi with this proposal, and they met with the King and (according to the minutes) obtained his agreement:

“The Obi further remarked that all the age grades societies (sic) could function as such but the improvement union should serve as a body representative (and) should control the interest of other societies.”

However, later minutes of 2 September record an angry discussion that suggests the Union’s dominant position was by no means secure. Mentioning the “Seven Age Grades” by name for the first time, members of the Union proceeded to directly attack this group:

“The Ogbo Isa: The President and Treasurer saw and interviewed the Obi who said that he would not countenance the new Ogbo Isa…. It was shewn that no member should support the Ogbo Isa in any way. A breach of this will lead to a dismissal of a member at once. Mr. Chukwura held that the Ogbo Isa should not live long because of its personnel and general inefficiency…. After long and interesting discussion it was moved by Mr. Mbanugo seconded by Mbanefo that no member of Onitsha Improvement Union should be an officer (added: or member) of the Ogbo Isa this should bind all members under the penalty of immediate dismissal.

“Mr Onwuatu suggested that it should form part of the regulations that no member should belong to any other society or club which is anti Onitsha Improvement Union. The President pointed out that the Union should formulate scheme of work to present to Obi and Council.”

In the aftermath of several very defensive motions suggesting the Union’s sense of the subversive potential incurred by the fact that each its members was also (formally) a member of one of these pan-Onitsha age sets, the President’s final suggestion, directing the group’s attention to the need for presenting a program of action to the King and his Chiefs which would justify a favorable response to the Union’s appeals, indicates that the merits as well as the prospects of the case remained very much in doubt. The topics suggested at this time for the forthcoming interview at the Palace included relations between the Union and the Obi and Council; suggestions for amending the council; council meetings to be held at least monthly; council minutes to be recorded in writing and submitted to the Government; council agenda to be circularised; and “the council to be expanded compared with other native states Ibadan, Abeokuta etc etc.”

Thus the Union’s immediate response to the call for a “scheme of work” was to formulate a set of plans for instituting substantial changes in the King’s Council itself, in the direction of greater formalization along Western lines. That this might appear threatening to the Chiefs (of whom most but not all were at this time illiterate) was surely apparent to the members, but their attention seems to have been concentrated on overcoming their organized age-mate opponents by displaying superior grasp of European councils and bureaucracy.

4. A Strategic Defeat at the Ime-Obi

The OIU minutes do not record that the members presented these suggestions to the Obi and Council at the subsequent meeting ,but this Palace event did not proceed as the Union had planned, as an apparently anguished set of subsequent minutes of 24 September detail :

“The Secretary made certain observations in respect of the activities of the new Committee of 49 asking if members still stand by their solemn promise to be ever faithful to the Improvement Union. The speech inspired members to lively discussion. It was shown on the whole that all the members stood by their declaration. Messrs. Onwualu and Osaka wished it to be stated what would be the fate of a member who was dismissed from his particular age grade for refusing to take the orders of the age grade as to being one of the representatives of the Committee of 49….

“It was pointed out that no age grade should be so prejudiced to pass such a judgement granted that that became real, the member concerned could safely denounce such a company which is anti Union.

“It was then unanimously carried that no member of the Improvement Union should accept an office as a delegate to the Committee of 49.”

The President then “gave the general analysis of the events which gave rise to this conflict by the Committee of 49.” After the Union had formulated a plan of work (” in advisory capacity to shew Obi and his council” ) and had prayed to the King to grant them an interview, the Obi kept postponing this meeting, until he opined that the chiefs were not yet inclined to grant the Union an interview”, and suggested that meanwhile some members of each age grade should be “embodied in the Union to make the whole thing of wider representation.” To this the Union had agreed.

“Later the Obi issued out circular meeting (sic) in which he warned all the age grades to send four representative (sic) to the Union which should be a central body for the improvement of the town.

“The age grades bolted away ignored this order and began anti union organisation…. They went to Obi and prayed for a hearing. A meeting was held between the Obi and this body, unkown to the Improvement Union. Here began the repetition of the Wolf and the Lamb diplomacy.”

Meanwhile, the Union sent a Select Committee to the Obi to arrange events for the forthcoming King’s Ofala Festival. “In consultation with the Obi,” the union sent a news telegram to the Nigerian Daily Times:

Obi and Ofala Festival

His Highness, James Okosi, the Obi of Onitsha

will hold his annual Ofala festival on

Thursday, October 8.

The Onitsha Improvement Union will play

an important role in the celebration in an

effort to make the occasion both elaborate

and remarkable.

The minutes continue:

“The Secretary on the day the telegram was sent saw the Obi and from his verbal instruction the secretary prepared a letter signed by the Obi convening a general meeting between the Onitsha Improvement Union, the agbala Nze society (the association of Ozo titled men in Onicha) and the ‘Committee of 49’. The object of the meeting was to see that both the Agbala Nze and the Committee of 49 send some representatives to the Union.

“The meeting was held in the Obi’s palace. The Committee of 49, the Improvement Union and the Agbala Nze made statements as to the formation of their particular group. The Improvement Union felt satisfied that all were well so long the organization was out for the improvement of the town. The Ogbo Isa or the Committee of 49 held that their mission was to take the reigns (sic) of Government. The Agbala Nze posited that all organizations should be headed by them as they head by virtue of their titles and dignity.

“The Obi summed up the position. He found to his own opinion that the Improvement Union was a well organised body but according to him some members of the Union were not steady. He then asked in view of this the Ogbo Isa or Committee of 49 to take the lead.

“This pronouncement by the Obi wounded almost the feeling of the members of the Union who never at any one moment were divided in any shape or form. However as a father would do to his children the members pledged their loyalty to his Highness.”

As this meeting drew to a close in an atmosphere of defeat,

“As a test case that the members were not split up and also with a view to strengthening the Union’s position financially, it was resolved that a voluntary subscription be raised by members at a minimum rate of 5 shillings a member. After a due discussion this motion was unanimously carried by 12 votes to 3.”

Thereupon Mr. I.A. Mbanefo offered to donate one guinea, and 5 others L1 each. Mr. J. Anionwu offered L2, and paid L1 of that on the spot “amidst great deafening cheers.” A subscription list was to be circulated for the other members to do their best, and arrangements were later made for publishing an account of the donations (“care being taken that the amount donated was not disclosed”).

5. Peter Achukwu and the Agbala-na-iregwu (“Those Who Support and Dignify”)

The OIU meeting with the Obi and his Chiefs described in the minutes of September 24 ended with a significant defeat for the union in its effort to penetrate (and in some measure begin to dominate) the formal traditional structure of Onitsha Inland Town. This failure occurred in a context of multiple revitalizing traditionalist movements, which were themselves being stimulated by the colonial reorganization of Indirect Rule, and included not only amalgamating Age grades but also some broader “democratic” (as well as resurgent-hierarchical) processes stirring within the Inland Town. Such reorganizations, to which C.K. Meek’s 1937 book on “Law and Authority” among Igbo-speaking peoples was partly addressed, were under way during the 1931-35 Interregnum, and in his book Meek said of Onitsha (which he characterized as “a centre of progressive ideas and many of its inhabitants are well educated and highly cultured persons”) ,

“It will be interesting to see how far they will be able to devise for themselves a constitution suited to their immmediate needs, or whether they will continue to throw the entire onus of this on the shoulders of the Government.”

During the founding of the OIU in 1935, Peter Achukwu, then a young Onye-onicha motor-mechanic (in his thirties), used his role as a leader of the Eight Age Grades to promulgate a system of “rules governing the Obi of Onitsha”, which then evolved (through his position as Secretary of that group) into an effort to design a written “Constitution of Onicha Eze-chima” to guide whole community political action.((The term “Onicha Eze Chima” “identifies the whole Onitsha community in light of its shared legends of origin.)) While the initial project culminated in a promissory document that was apparently signed by the eventually successful candidate in 1932,9, the more substantial aim had less tangible results (though it may have produced a subtly significant cultural transformation).

Though historical documents so far available to me do not permit definitive statements about this process, Achukwu’s own records (items of which he occasionally shared with me when we discussed both past and present in his home, often over a dram of advocaat) show his systematic and persistent effort (in his role as Secretary of the Eight Age Grades) to create an Inland Town system of government based on precolonial categories but reformulated in light of a British Parliamentary model. The Achukwu Constitution undergoes several stages, the details of which are too complex for discussion here, and what follows is merely a sketch excerpted from several incomplete sources, to provide a sense of his intent:

First, defining “constitution” as “the sum total of all those principles according to which Onitsha is governed”, Achukwu affirms that this constitution is a “limited monarchy” in which “The Obi, the Ndichie (Chiefs), and Agbalaniregwu (“Those Who Support and Dignify”) form “the three estates of the realm. The Legislative, Judiciary, and Executive power is shared by the Obi and his subjects.”

After a section (entitled in one version, “Power and privilege”) describing the rights and responsibilities of the Obi, the Constitution states that the Onitsha Chiefs are “the Council of Elders. This council is purely an advisory body and assists the Obi in all his deliberations. They are representatives of the Obi in their various quarters.”

This definition, which sharply downgrades the potency of Onitsha chiefs, presages a strong affirmation of the importance of those sometimes also categorized as “Commoners” (or, as Ibeziako might have said it in more denigrating terms, “plebs”):

“Agbala-na-iregwu”

This consists of the OZO men, the di-okpala (senior lineage priests) or spiritual lords and the untitled men. They form a big portion of the nine quarters of Onitsha. Their representations in all the town meetings summoned by the Obi is (sic) essential. Before any bill becomes law of the country, it must be presented to the ndichie by the agbalaniregwu for their considerations and supported thru Ogbo-na-chi-ani (Age Grade Ruling the Land). If the bill is supported by the ndichie it is then submitted to the Obi for his approval. No bill can be submitted to the Obi for approval by the ndichie if such a bill does not receive the unanimous or majority support of the Agbala-na-iregwu.”

Other versions he produced more explicitly equate the Agbala-na-iregwu with the “House of Commons”, the Ndichie with the “House of Lords”. Consistently he emphasizes that creativity in the form of legislation should begin with the Commoners, consent (with perhaps some modifications) residing with the chiefs and the King. While the Achukwu Constitution does not mention the Eight Age Grades by name, their role is implicit in the reference to the Ogbo-na-chi-Ani (which would presumably but not necessarily be the senior set of Ogbo), while including the Ozo-titled men as “Commoners” sets up a broad opposition between a vast majority of the populace versus the Obi and his Council of chiefs. this was quite a radical re-conception of some components of this traditionally-complex society, one that would convert it into something much more “democratic” than it was previously conceived.

While the document itself was never formally accepted by the authorities it designates, it gained wide circulation among Onitsha people both at home and “abroad”. My Achukwu files contain a copy of a letter from him in March of 1938, addressed to Nnamdi Azikiwe in Lagos, “to remind you of the work as regards the draft Constitution handed over to you for amendment for over three months now.” Although neither Zik’s answer nor the exact subsequent fate of the document is known to me, by 1960 the centrality of the Agbala-na-iregwu as a concept was substantially established in Onitsha Inland Town opinion outside the immediate circles of chieftaincy.

Whether this social category existed in precolonial Onitsha society, or was a creation of the time just described, is an issue I cannot decide. In The King in Every Man (1972). I inferred that it was precolonial, on the grounds that its several ingredients could definitely be discerned in documentary evidence from the 19th century10, but the term does not to my knowledge appear in historical literature until this more recent time. Members of the OIU referred to it only as the “so called Agbalaniregwu“, implying an illegitimacy in their eyes, but even while rejecting it they alluded to their own lack of effective social support, for example in the Minutes of October 30th 1937 where their members resolve to convene a

“meeting with representatives of all Quarters of Onitsha”… for the purpose of cementing better affectionate relation between the Union and the majority of the townspeople… to explain away certain aims and objects of the Union.”

So if “Those Who Support and Dignify” was a categorical innovation from the 1930s, it represented a synthesis of some strong tendencies already present in older Onitsha social structure, but which became more strongly salient when Colonial policies purporting to rule more thoroughly by means of “traditional structures” emerged. The OIU home branch leadership remained however consistent in their rejection of such democratic inclinations.

6. Pivotal Triumph for the OIU

Following their Inland Town defeat at the hands of the Seven Age Grades as recorded on September 24, 1936, OIU members proceeded in their meeting of 30 September to draft a letter to the Obi asking if he wished the Union to play any role in the forthcoming Ofala Festival. While his reply is not recorded, an account of the Festival written by John Stuart Young (an English trader and writer who lived for many years in Onitsha Waterside, was befriended many Onitsha people, and significantly influenced their culture) was placed in the Union minutes at this point, and this document records the Union’s role.

After celebrating the holding of Onitsha’s first Ofala Festival in five years, Stuart-Young (writing under his then-current nom de plume, “St. John”) described the arrival of various crowds, including European guests and the assembly of the Chiefs. As he put it, “The work was most ably supervised by officers of the Onitsha Improvment Union, the Salvationist of the welfare of the Town.”

After the Chiefs performed their traditional War Dances, the Obi made his three customary appearances before the crowd, escorted by his Chiefs and their retinues, and then

“There was an address to the Assembly by His Highness…. Although Obi James Okosi is more than ordinarily literate (proven by the extreme simplicity and directness of his message to the Onitsha people) he wisely chose to have his speech read aloud. This task fell to the lot of the always enthusiastic Honorary Secretary of the Onitsha Improvement Union Mr. M. Ogo Ibeziako.”

While there was a traditional taboo against the Obi of Onitsha speaking in public, his appropriate traditional surrogate should have been the Onowu his “Prime Minister”, rather than a young untitled man. But the text of the speech was in English, and it addressed matters of interest to the Europeans present, urging his people to “take keen interest in the administration, and urging the young people to “learn various kinds of trades especially in native crafts and agriculture in order to save the country from impoverishment and decay”.

Such words were best spoken by one who had the sophistication of a Chief Typist from the Resident’s Office. (The Prime Minister did afterwards address the assembly on behalf of the Chiefs, pledging their allegiance to the new Obi and emphasizing “the pleasure everybody felt” at the occasion.)

At the conclusion of the ceremonies, Mr. Rockson, the Gold Coast Photographer, made a series of full plate studies, which Stuart-Young briefly describes:

The Resident, W.H. Lloyed (sic, Lloyd, RNH), Esquire and Mrs. Lloyed were seated next to the Assistant Commissioner of Police A Caclachlan and his wife; and they were in front of the camera while Mr. Odogwu (Headmaster of the Holy Trinity School) moved a vote of thanks, on behalf of the Onitsha Improvement Union, to the Resident.”

Stuart-Young concluded his account with an interview with the Obi, who “gave praise to the Onitsha Improvement Union for the splendid work they had done to bring about such an unqualified success”, applauded the work of the Union’s Secretary (Mr. Ibeziako), and offered “the Obi’s salutations and those of the Onitsha Improvement Union” to the various branches of the Union abroad.

This account was in fact written for newspaper distribution, and no doubt found its way “abroad”. Its content (as well as its mode of distribution) illustrates how the Union, despite its great tactical defeat within the arena of the Obi‘s court inside the Inland Town social system (at the hands of an organization much more effective in mobilizing mass community opinion), was nonetheless tactically superior to the Seven Age sets in other ways, namely its capacity to organize distinctively Western forms of interaction and communication, and thus to bridge the gap between the African and European communities in Onitsha. In this sense, it was (despite its formal “defeat” at the Palace) able to make itself indispensable within the Inland Town itself, because the latter needed individuals and groups capable of building such bridges.

On September 30, the OIU also abruptly voted a subscription for surveying and constructing a “tennis court etc.”, which was completed (and largely paid for) by 17 November. On 20 November an emergency meeting was held to organize a “Send off” for the official Resident of Onitsha Province, W. H. Lloyd. (“Send off” parties for important people transferring elsewhere were an entrenched practice among Onitsha educated people well into the 1960s.) When it was learned that the local African Club intended to hold a tennis tournament in the Resident’s honor on the same date, the OIU arranged for a combined Send off to be held at the OIU site. “three separate palm booths” were to be erected, and “twenty prominent Africans” and all the town’s Europeans were invited.11

A report on the social repercussions of this Send off is contained in an unsigned and undated account placed in the minute book:

ONITSHA IMPROVEMENT UNION: HEALTHY AND RAPID PROGRESS

“Having won the franchise from the first of the intelligentsis” (sic) of the African Community, and (by degrees) convinced Government, through the agency of the various Political Officials of the District, of the Union’s utilitarian objects, we are glad to report a very healthy and speedy development of the conception.

“At the head as Patron is the OBI. That monarch has imbibed modern ideas, and is willing in every possible way to foster the dream of a Native Administration that (duly sponsored by the right European mentor) shall ultimately be able to look after its own affairs. There seem at this time, therefore, proofs that the recently appointed Resident of the Onitsha Province, Captain Dermot P. J. O’Connor will see carried into concrete affect (sic])the ideas which he maintained while acting at Onitsha as District Officer.

Subsequent to the Reception, recorded in these pages, when the former Resident, Mr. W.H. Lloyd was present at the Opening of the Union’s new Tennis Court, Onitsha Town, the members seem to have grown determined to strike while the iron was hot. At the Opening of the Tennis Court over fifty Europeans congregated, together with an immense concourse of Africans, headed by Obi James Okosi and his Councillors. As a result of a deputation… there was a formal interview granted to the Improvement Union by Captain O’Connor. The Resident listened with great attention to certain submissions of the Members of the Union, and the advice that he gave was of a friendly and fatherly kind.

“The following day, the same Deputation waited at the Local Authority`s Office, where the newly arrived Mr. R. K. Floyer gave patient and considerate hearing to the Members. The main items were dealt with at most commendable speed and it was thus shown that the Onitsha Improvement Union had aptly chosen its name for the Improvement of the Motor Park was placed on Government agenda instantly. The congestion on Bright Street… had been causing disquiet for a long time. The suggestions will doubtless lead to the produce market being shifted a little nearer to the river, so that the road frontage of the Park may be made longer for the accommodation of the annually increasing number of lorries used for Road Transport to all the interior towns and villages. It is a splendid conception, and one for which the public in all parts of the town may feel duly grateful.

“Hence it was that on Saturday, December 19th, the Resident and the Local Authority together met the Improvement Union at the Motor Park. Suggestions were noted in detail, so that the earliest attention for reconstruction might be given. The Union must be encouraged (in as much as it represents the considered judgement of leading Africans of the Town) to make these ideas known from time to time, and thus help European Officials. These latter have to become familiar with all the pros and cons of local requirements so as to form constructive decisions without a lot of unnecessary detail and correspondence among interested parties.”

The account goes on to record some details of yet another social event:

“As a practical illustration of what may be done by an Official, if he shows the right spirit of receptivity, we may place on record that Mr. and Mrs. R. K. Floyer held an “At Home” and Reception on Sunday Evening, December 20th. As Local Authority, Mr. Floyer has already been here with Mrs. Floyer. The African Officials and their wives, together with an odd one or two members of the secular coloured community from commerce and the schools, were both surprised and delighted at the congeniality of the atmosphere that met them when they arrived at the Reception. In every way Mr. and Mrs. Floyer laid themselves out to charm. From half past five until half past seven the thirty odd guests were liberally entertained, and host and hostess remained with them throughout, each taking part in intimate talks with the guests, both individually and in groups. A more perfect understanding of each other’s point of view is bound to result. A group photograph was also taken.

“Mr. C.B. JANNEY, Local Treasury Assistant, gave the vote of thanks, as evening drew on. His speech was full of humour, and caused much laughter. The Vote was responded to amid loud applause. Mr. Floyers, on behalf of himself and his wife, said that the pleasure had not been at all one sided, in as much he looked back upon the past couple of hours as among the most pleasant in his life. Three cheers were given before assembly dispersed, crowned with the usual refrain, For He’s (She’s) a Jolly Good Fellow, and everybody went home full of admiration at this breaking down of the barriers of Colour.”

That such efforts bore subsequent fruit seems confirmed not only by annual Government reports at the time extolling the “educated elements” of the Province as “most progressive”, but more specifically by a letter from the Acting Resident to the Onitsha Obi and Council in August 1937, wherein, after mentioning the carrot of prospective Council control of Township revenues, he points to the fact that the Council still has vacancies, and asks, Why not fill them with younger, more educated men:

“Already, today, you permit the members of bodies such as the Onitsha Improvement Union to approach you upon matters of public interest could you not go further and admit them to your deliberations by making them full members of the Council?”

Then, on September 23, 1937, the Onitsha Market caught fire and many market stalls were destroyed. The OIU minute books record a meeting held in the Onitsha Native Court on September 27:

“Present.

The Local Authority (J. M. Stow Esq.)

The Obi of Onitsha

The Ndichies [chiefs]

The members of Onitsha Improvement Union

The general community of Onitsha

S. C. Obianwu Spokesman for the Ndichies

P. H. Okolo Spokesman for the Union and general

community of Onitsha

I. A. Mbanefo Interpreter

M. Ogo Ibeziako Secretary”

“Mr. Okolo… aired the grievances of the people as follows:

1. That since the Onitsha Market stalls were burnt… there have been some unpleasant rumours concerning the matter of allotment of the market stalls…. In the interest of peace, equity and justice a deputation of the Improvement Union… met the Local Authority on the 27th of September morning in the market and prayed for this meeting in order that we might ventilate our grievances.

2. That unlike the other women folk of the neighborhood in doing farm work, making of palm oil and kernel etc. the chief occupation of Onitsha women from time immemorial lies in trade.

3. That looking through the list of all stall holders in Onitsha Market register today, it is lamentable to find out that the percentage of the stalls allotted to the genuine aborigines is rather negligible.

4. That in other localities, such as Lagos, Ibadan, Benin, Calabar and so on the natives of the places have prior claim and do have greater consideration for the market stalls before the strangers. Whereas at Onitsha the opposite is the case and the word ‘Onitsha’ market is a misnomer in that the stranger elements have certainly ousted the very native owners of the place.

5. That sad still to narrate… these strangers pay their rates and taxes into their respective native treasury so as to benefit their fatherland. It then devolves upon the natives of Onitsha to pay for water rates and taxes in order to maintain and upkeep the town and this very market which today the strangers feel themselves justified to claim as a common ‘Booty’.

6. That under the circumstances it is respectfully urged that the new market stalls should be reserved exclusively for the natives of Onitsha proper. Then at the expiration of the current year’s stall rent, the whole system to be overhauled to give adequate and ample stalls to the self sacrificing native owners of the place.”

After Mr. Okolo’s presentation, Mr. Obianwu spoke on behalf of the Chiefs in supporting these views, and, reporting rumors that the staff officials of the Local Authority were undertaking the allocation of stalls, requested that the Local Authority himself should supervise the allotment. The Local Authority replied that he had already received 400-500 applications for the new stalls which might amount to about 60 in number, and agreed that a fairer distribution should be devised. He promised to discuss the matter at the next Township Advisory Board meeting, and reminded the people that “in the near future it might be that the Obi and Council would have control of the market.”12

The December 3 minutes record that “the bulk of the applications” for market stalls had been submitted to the Obi, and that “the Union was invited to take part in the sorting of the individual applications.” Thus the Union’s efforts to intercede with the Local Authority had again borne fruit, and members were directly assisting the Obi in this economically crucial process of distributing rights to market stalls (thus ensuring the security of Ndi-Onicha as major holders of market stalls, a pivotally valuable rental resource).

On 22 June 1938 the Home Union’s delegates to the forthcoming Onitsha Provincial Conference were directed to propose that membership in the traditional title system should not be a criterion for holding a position in the next version of local government. On August 2, under the heading Onitsha Native Administration Council, the Union resolved that the basis of the Council should be “broadened to embody representatives of educated elements and all shades of opinion,” and stated a formal proposal for presentation to the Conference that Onitsha should be divided into seven administrative units comprising six traditional village group divisions of the Inland Town and one for the Waterside. For each of the seven divisions there would be chiefs as representatives, and in addition two or more named educated men. Of the 20 non chieftaincy appointees recommended in the OIU proposal, 7 were foundation members of OIU and most of the others were known supporters of it.

The Government’s response to this proposal was immediate, and at the OIU meeting of 25 August, the “President expressed the satisfaction it gave the union for the recent appointment to the Council membership which consisted mostly of the members of the Union.” It speaks, he said, volumes about the progressive advance of the Union. By the end of 1938, President P.H. Okolo, Secretary M.O. Ibeziako, and founding member I.A. Mbanefo (the three most prominent figures in the minute books to this date) were now members (and Ibeziako became the first Secretary) of the new Onitsha Native Administration Council (ONAC). In 1939 British colonial officials were warmly praising “The vigour of the Obi & Council of Onitsha with their additional 20 members of the intelligentsia”13.

Thus the OIU leaders moved past their defeat at the hands of Ndi-Onicha indigenous leaders to gain a major triumph in the now clearly secularizing community.

Even in their triumph, however, these “intelligentsia” members of the ONAC, all of them Onitsha men, could not avoid finding themselves repeatedly embroiled in conflicts involving various sectors of Inland Town traditional politics (including the Obi, his chiefs, Ozo-titled men, the Age Grades, and various Onitsha women’s organizations), some of which reflected intensifying opposition between advocates of modernity and representatives of teraditional authority.

Perhaps the most striking event I encountered in the documentary record occurred when M.O. Ibeziako, still Secretary both to the OIU and to the ONA Council and also a clerk in the Resident’s office, “transgressed the Nmo” (the mmanwu, the Onitsha Incarnate Dead Masquerade organization) and was personally rescued by then-Resident D.P.J. O’Connor from being dealt with (and very likely killed) within his own village in the Inland Town.((See the West African Pilot May 13, 1940 for one account of the incident, and Henderson 1972: for descriptions of traditional roles of the Masquerade in old Onitsha Town.)) Obviously, a serious case of hubris was involved. Soon afterward, Ibeziako was transferred to the Nigerian Secretariat in Lagos, removing his Western-vanguard skills from their local expression (and turning them anew, into more radical scenes of socio-political reference in the national scene) while the OIU continued to confront an unbroken network of traditionalists back at home.

7. The Meaning of “Igbo” (continued)

During 1937 the minute books record a number of apparently quite congenial interactions between the OIU and the “Ibo Tribe Union”14, in which the OIU was at that time represented. However, as the OIU now achieved effective participation of “educated elements” from the Inland Town in the Local Government, it came into intensifying conflict with the growing (and also educated) community of other Igbo speakers residing in Onitsha.. On October 30, the minutes refer to a “damnable article contributed by a Non Onitsha” on the matter of Onitsha Market stalls. This constitutes the first use of this identity-label in the Union’s records (presaging the long-lived political identity of “Non-Onitsha Ibos” coming later). The meeting of December 3 also reported the views of members of the OIU branch in Kano, who emphasized that the appellation given to Obi Okosi on the OIU Almanac should include the word “Eze”, in order “to show a line of distinction between us and Ibos.”

This dedicated adherence to a “line of distinction” points to persisting contradictions in the OIU model of the Onitsha social world, looking back to the first portion of this page and forward to the next one. In its fundamental behavioral patterns, the OIU projected a strongly Europeanized “intelligentsia” image upon the hometown screen, using this image to set themselves apart from (and to claim superiority to) other local Africans. At the same time, they presented as a prime feature of Onitsha identity the adherence to a hierarchical model of power and authority, now however legitimized not primarily by achievements in war but more succinctly in Western life styles (the collar & tie men who now may rule the “plebs” in a more “Enlightened” way than have the old chiefs and king). In conflating these two aspects, they emulated patterns long pursued by their main Colonial masters, but the social and cultural context was changing: those aspects of the Western world (including Christianity) which imply “democratization” were now stirring, and the OIU had at least two problems in “drawing a line”: how could they gain power in the Inland Town while separating themselves, as elitists, from their own Age Grades (who were staking their claims partly in light of democratic values), and how could they justify the governing claims of “intelligentsias” without opening wider doors, since increasing numbers of Ndi-Igbo could also claim membership in this superior category? (This latter form of “stirring” was emerging, too obvious to ignore, among the Ndi-igbo residents of the town..

Our OIU seems to have had no effective answers to these questions, and its subsequent evolution was to slide in a direction of continual decline. Its main creators were anyway now moving elsewhere, seeking to make their marks in other venues.)

- Note: My evidence for the OIU derives mainly from its Home Branch Minute Books, which I borrowed briefly from Jerry Orakwue in 1961. The Minutes described in this chapter were recorded by the Union’s new Secretary, M. Ogo Ibeziako, whose early writings are remarkably detailed and reflective of the group’s efforts to forge symbols of the group’s emerging sense of self-definition. I also want to acknowledge a paper written for a graduate student seminar I conducted that focused on my Onitsha materials, written by an unusually perceptive political science graduate student at the University of Arizona named Timothy Luke. Ideas presented there contributed significantly to the page that emerges here; see the Bibliography in chapter 9. [↩]

- See Henderson 1972:267-72, 319-24 for symbolic discussion of these emblems. [↩]

- Azikiwe 1937 [↩]

- A highly significant exception to this generalization is reference to land disputes between Obosi and Onitsha, which began to appear in court at this time [↩]

- See Henderson 1972: 378-9, 492-3 for examination of the role as it appeared in precolonial contexts. [↩]

- In this work I defer to the Onitsha English translation of Ogbo as “age grades” rather than the more precise anthropological term for these social groups, “age-sets” (which I employed in The King in Every Man, Henderson 1972). The ambiguity between “seven” or “eight” reflects the fluidity of Onitsha age set organization (sets sometimes merge or divide [↩]

- Achukwu looms large in our story of Ndi-Onicha in the 20th century, a figure comparable to (and quite in contrast with) that of our OIU Secretary M. Ogo Ibeziako. Both men are Greats in our story, bearing in mind Lord Acton’s (no doubt disputable) dictum that “All Great Men are Bad.” [↩]

- Standard Six” refers to a full primary school education, surely a considerable achievement for 1936 but apparently not enough to warrant prominence in the Home Branch of the OIU. [↩]

- After his Installation however Obi Okosi II proceded to violate many of these rules rather drastically, the justification for this being the convenient tradition that “the Obi can be bound by no human laws”. [↩]

- See Henderson 1972: . [↩]

- Palm booths” are ramadas provided for rituals held outdoors, to protect participants from sun and rain. The importance of tennis playing as a social bridge among African elites, and between them and their British overlords during the 1930s, is reflected in Azikiwe 1970:237, 241, 267, 281. [↩]

- C31, DO 722 28 August 1937, O’Connor to Obi and Council [↩]

- 1939: 11679 vol XVI, OPAR’s [↩]

- For history of this group see Coleman 1958, Sklar 1963. [↩]