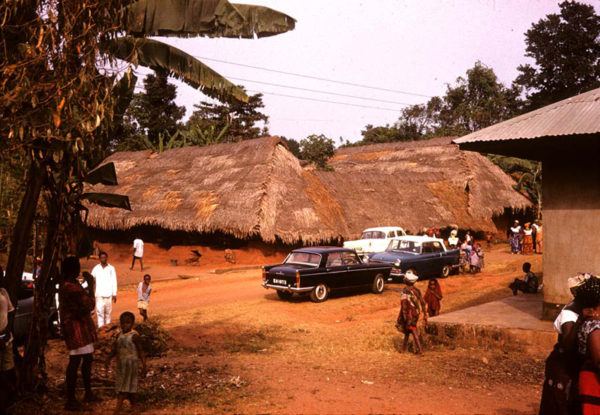

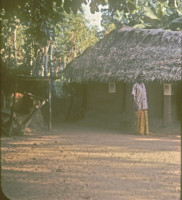

Above, a View of Umera Ozi’s House from the South, 1960

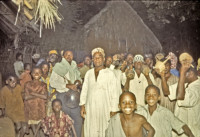

When I first photographed this uniquely magnificent traditional building in color above, a funeral was underway for the late Akunne Agusiobo, a member of an Odoje family, and the center of the ritual activity where I was taking the photograph was occurring directly across Ugwunabamkpa Road from the Ozi‘s house. The vehicles present were associated with the funeral, not directly linked with the Ozi and his house at this time.

[Note: click on any image you want to enlarge.]

Before I survey this topic, I should point out that, in traditional Onitsha (as in many African societies), certain houses play central roles in defining social identities and coordinating group activities of the people. Here, they provide ritual centers dedicated largely to ancestors, primarily those forming lines of “fathers” and “sons” but also (as you will see) women and crucially important social connections formed with and through them. Sacred concepts and images serve to focus the meanings of all kinds of social relationships, and these are often labelled through physical forms.1

Umera Ozi’s house is the grandest Iba (Ancestral House) of carefully “Traditional” construction in all of Onitsha in 1960-62, and (though I failed to ask) I suspect it was built by master craftsmen from Awka vicinity (as also, probably, was Obi Okosi II’s palace, completed in 1919). When I first see it early fall 1960, Its posts and walls are covered with multicolor images (including bas-reliefs) of great beauty (and no doubt reflecting important ritual meanings). Note in the enlargement of the image at left, you can see that the entryway pillars are not obviously painted. They have icon markings on them, though. 2 At right, observe the framework for an Oda Guardway, located just downhill along Ugwunaobamkpa Road. I do not learn the exact meaning of this particular structure for this portion of Odoje (the Oda fixture as a type denotes a social-moral boundary between local groups that requires medicinal protection/defense for those who cross it).

Not long after the two earlier images above were captured, the Nigerian Government declares the place a national treasure (a “Museum” designation), whereupon the Ozi‘s wives proceed to cover nearly all available interior spaces with an all-blanketing whitewash paint, which they then paint over again with black (as readers may see on the entry pillars at left), and since I have not previously entered the place for close examination with my camera, those figures and paintings are now lost to view (forever, I fear). If you click on the image at left (taken later, when I attended the funeral), you can see the the whitewash and black images covering the entryway pillars. You will see more examples of the whitewash-blackpainting work below.)

The Ozi‘s house is an especially fine form of the Iba — the others present in Onitsha in 1960-61 are considerably simpler (though basically alike in their formal elements). I will describe some of these forms before further exploring Iba Umera Ozi.

The Ancestral House as a Hallowed Onitsha Type

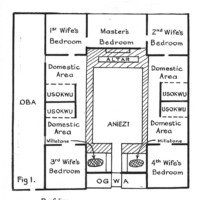

The Iba is a centrally visible unit of the traditional Onicha social and moral order, representing both a unit of a “village” (ogbe) and a “patrilineage” (umunna) within the larger society. As such, its form is quite distinct from those of most nearby igbo-speaking neighbors, and reflecting formal similarities to elite houses found among Western Igbo speakers, the people of Benin, and the Yoruba. I described its properties in some detail in The King in Every Man ((Henderson 1972:166-76)), and provide my diagram of it from that book, here at right.

The Iba is a centrally visible unit of the traditional Onicha social and moral order, representing both a unit of a “village” (ogbe) and a “patrilineage” (umunna) within the larger society. As such, its form is quite distinct from those of most nearby igbo-speaking neighbors, and reflecting formal similarities to elite houses found among Western Igbo speakers, the people of Benin, and the Yoruba. I described its properties in some detail in The King in Every Man ((Henderson 1972:166-76)), and provide my diagram of it from that book, here at right.

Frank Mbanefo, a native of Onitsha and an architect, provided a valuable account in a 1962 copy of Nigeria Magazine, which focused on the elemental forms, Here at left he presents a somewhat different version of the living arrangements, but the basis pattern holds. Note his provision of paired grinding stones as part of the kitchen.

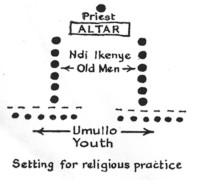

Frank Mbanefo, a native of Onitsha and an architect, provided a valuable account in a 1962 copy of Nigeria Magazine, which focused on the elemental forms, Here at left he presents a somewhat different version of the living arrangements, but the basis pattern holds. Note his provision of paired grinding stones as part of the kitchen.  At right, he emphasizes the social centrality of the place: when formal ritual meetings are held at the iba, the wives’ positions are marginalized and the social roles of men are carefully ordered: the senior priest sits behind the primary altar, the “elders” along the flanks of Ani-Ezi, and the young men (“Children of the Ilo ” or village square) in the Ogwa, the entryway, guarding the door.

At right, he emphasizes the social centrality of the place: when formal ritual meetings are held at the iba, the wives’ positions are marginalized and the social roles of men are carefully ordered: the senior priest sits behind the primary altar, the “elders” along the flanks of Ani-Ezi, and the young men (“Children of the Ilo ” or village square) in the Ogwa, the entryway, guarding the door.

Mbanefo drew, alongside this image at above right, a major Onicha ritual object, the Okpulukpu, a symbolically carved wooden box shown above. This object represents the spiritual dwelling-place of a titled ancestor, its paired parts fitted together, the interior containing treasures to be known only by Ozo-titled men like the ancestral figure who took his sacred ozo title. In each Iba, one or more of these shrine objects are kept, their numbers accumulating over time, providing miniature spiritual houses for the hallowed Persons to come and receive offerings from their living descendants.

Mbanefo drew, alongside this image at above right, a major Onicha ritual object, the Okpulukpu, a symbolically carved wooden box shown above. This object represents the spiritual dwelling-place of a titled ancestor, its paired parts fitted together, the interior containing treasures to be known only by Ozo-titled men like the ancestral figure who took his sacred ozo title. In each Iba, one or more of these shrine objects are kept, their numbers accumulating over time, providing miniature spiritual houses for the hallowed Persons to come and receive offerings from their living descendants.

We now look more closely at some examples of these houses:

At left, you see two houses. the one to the left is the home of an ordinary person, with a simple gabled roof. In that same house on the right, however, you see more clearly that a living tree is growing out of its center, which identifies it immediately as an iba, in this case one of the Omekam family of Umu-Anyo (a sub-village in Umu-Aroli). At right you see the interior, its thatched roofs designed to draw rainwater into the Ani-Ezi (which then runs out through a drain provided, called “ulolo“, see below). Here the household head sits at the throne, his wife beside and below him to his left, beside her kitchen. The tree in the center is an egbo (the First Tree that grew on the Land), and represents the Iba-holder’s spiritual self. The bottles arrayed along the earth before the throne are not a formal-defining feature of the iba as a type, but they do here reflect the fact of past ritual performances where drinks have been offered to Spirits and Ghosts.

At left, you see two houses. the one to the left is the home of an ordinary person, with a simple gabled roof. In that same house on the right, however, you see more clearly that a living tree is growing out of its center, which identifies it immediately as an iba, in this case one of the Omekam family of Umu-Anyo (a sub-village in Umu-Aroli). At right you see the interior, its thatched roofs designed to draw rainwater into the Ani-Ezi (which then runs out through a drain provided, called “ulolo“, see below). Here the household head sits at the throne, his wife beside and below him to his left, beside her kitchen. The tree in the center is an egbo (the First Tree that grew on the Land), and represents the Iba-holder’s spiritual self. The bottles arrayed along the earth before the throne are not a formal-defining feature of the iba as a type, but they do here reflect the fact of past ritual performances where drinks have been offered to Spirits and Ghosts.

At left, the iba of Ezekwezili (Jerry Ugbo), the designated Senior Priest (diokpala) of Umu-Anyo. In this frontal view, you can see that the door is open and the place is illuminated from within through the open atrium (a ritually and socially important fact — the “fortress” aspect is significant).3 At right, the view of ani-ezi you gain here (and here, paved; this is quite unusual) is taken from the throne side. You can see at the base of the egbo tree, a small anthill-clay mound. This designates a ritual surface (with the mound a maternal significance), a place where sacrificial offerings are made.

At left, the iba of Ezekwezili (Jerry Ugbo), the designated Senior Priest (diokpala) of Umu-Anyo. In this frontal view, you can see that the door is open and the place is illuminated from within through the open atrium (a ritually and socially important fact — the “fortress” aspect is significant).3 At right, the view of ani-ezi you gain here (and here, paved; this is quite unusual) is taken from the throne side. You can see at the base of the egbo tree, a small anthill-clay mound. This designates a ritual surface (with the mound a maternal significance), a place where sacrificial offerings are made.

At left, a view of the throne (with its altar space) in Jerry Ugbo’s house, and at right a closer image across the altar space showing some of the important ritual objects that are part of this iba. You can see clearly a set of ozo-title staves (belonging to ancestors), which are leaned against the wall, their bases seated in a box containing what are called collectively ndi-mmuo (the ghosts). Beside this box lie a rather substantial array of okpulukpu (shiny-black, indicating they have received regular blood offerings). This collection tells you immediately that this is a very important Ancestral House — representing the entire descent-group of Umu-Anyo. However, since Jerry Ugbo has not completed his own Ozo title, he is not able to preside over Umu-Anyo rituals that involve titled men of this village unit; for that purpose a designated titled man of the descent group must act for him in such rituals. That Jerry Ugbo aspires to higher achievement is however very much indicated in the size of his Ikenga (which stands against the wall above the assembled okpulukpu). The size of this particular figure reflects the scope of one’s ambitions.

At left, a view of the throne (with its altar space) in Jerry Ugbo’s house, and at right a closer image across the altar space showing some of the important ritual objects that are part of this iba. You can see clearly a set of ozo-title staves (belonging to ancestors), which are leaned against the wall, their bases seated in a box containing what are called collectively ndi-mmuo (the ghosts). Beside this box lie a rather substantial array of okpulukpu (shiny-black, indicating they have received regular blood offerings). This collection tells you immediately that this is a very important Ancestral House — representing the entire descent-group of Umu-Anyo. However, since Jerry Ugbo has not completed his own Ozo title, he is not able to preside over Umu-Anyo rituals that involve titled men of this village unit; for that purpose a designated titled man of the descent group must act for him in such rituals. That Jerry Ugbo aspires to higher achievement is however very much indicated in the size of his Ikenga (which stands against the wall above the assembled okpulukpu). The size of this particular figure reflects the scope of one’s ambitions.

Some activities relating to Iba

Historically, the Iba is the traditional center for many central Onitsha personal and social activities, from birth to death. As Frank Mbanefo put it, “During festivities, the decoration includes the hanging of tapestry and various carvings in wood, calabash and ivory on the walls…. [Tradtionally], The Onitsha family… obtains its relaxation through dancing, singing, and various types of indoor games. All these activities take place on the ani-ezi, , where the family congregates after the day’s work is over, to enjoy themselves, singing, dancing, acting and telling stories.”4 Formal meetings to make decisions regarding various descent-group or village issues are of course of central importance. I did not witness many of these activities as they occurred in the strongly traditional houses, but in 1960-61 funerals definitely revolved around them and I did see a number of those.

Activities occur within them and also outside, where they may provide an orienting frame for events staged around them. For example, in January 1961, I attended a portion of the Ikwa Ozu (Lamentation, or “Second Burial”) of Chief Oziziani of Ogboli-Eke. As Helen and I observed (in The King in Every Man and in her dissertation), Lamentations are joyous — they mark the incorporation of the deceased into the ancestral group — and in the case of a very prominent man like the Oziziani, quite elaborate. In the image at right, you can see a substantial crowd, mostly dressed in their finery, assembled in from of the Oziziani‘s Iba, the thatched building in front of which stand a group of the Daughters (umu-ada) of the deceased, guarding the Igbudu (the “mock coffin” which stands in for the one previously used for the deceased), the box which will receive symbolic objects associated with him. In this image the box, covered with white cloth, has been placed just above and behind the Daughters, who remain in vigil with him during this time. Later It will later be taken inside the Iba and be buried there, in the same location as his previous burial.

Activities occur within them and also outside, where they may provide an orienting frame for events staged around them. For example, in January 1961, I attended a portion of the Ikwa Ozu (Lamentation, or “Second Burial”) of Chief Oziziani of Ogboli-Eke. As Helen and I observed (in The King in Every Man and in her dissertation), Lamentations are joyous — they mark the incorporation of the deceased into the ancestral group — and in the case of a very prominent man like the Oziziani, quite elaborate. In the image at right, you can see a substantial crowd, mostly dressed in their finery, assembled in from of the Oziziani‘s Iba, the thatched building in front of which stand a group of the Daughters (umu-ada) of the deceased, guarding the Igbudu (the “mock coffin” which stands in for the one previously used for the deceased), the box which will receive symbolic objects associated with him. In this image the box, covered with white cloth, has been placed just above and behind the Daughters, who remain in vigil with him during this time. Later It will later be taken inside the Iba and be buried there, in the same location as his previous burial.

In this image at left, one of the “Age-Grades”5 related to the Oziziani dance in parade in front of the Iba. What you see here is mostly the yellow-headdresses of the women of the Grade (or Set). At right , the “Douglas Age-grade” (so named because the birth range of the group coincided with the 1906 assignment of this infamous British officer to a position of power in Onitsha) dances past the Iba, the men in front (Ozo men brandishing their elephant-ivory horns), the women dancing and singing behind. 6 The Head Mourner of this funeral, second son of the Oziziani, stands at near right wearing his father’s two-feathered red chieftaincy cap normally appropriate only for the chief himself. This designates his role as a successor to his father. Beside him at far right, two female mourners from the descent group.

In this image at left, one of the “Age-Grades”5 related to the Oziziani dance in parade in front of the Iba. What you see here is mostly the yellow-headdresses of the women of the Grade (or Set). At right , the “Douglas Age-grade” (so named because the birth range of the group coincided with the 1906 assignment of this infamous British officer to a position of power in Onitsha) dances past the Iba, the men in front (Ozo men brandishing their elephant-ivory horns), the women dancing and singing behind. 6 The Head Mourner of this funeral, second son of the Oziziani, stands at near right wearing his father’s two-feathered red chieftaincy cap normally appropriate only for the chief himself. This designates his role as a successor to his father. Beside him at far right, two female mourners from the descent group.

A culminating public moment for this Lamentation is the arrival of the Ndichie (Oziziziani’s fellow chiefs), who kindly pose for a group photograph (at left), then they are then led by the mourners further away from the street to a place prepared for their reception and entertainment (their procession is shown here at right).

I do not witness the further details of this “Second Burial”, but I do

attend a portion of a much smaller one from the Umu-Anyo subdivision of UmuAroli, Umu-Alabo branch, which is the immediate descent group of my close friend and research assistant Ifekandu Umunna. Here I will present the full array of photos I took at this funeral, which will give another sense of the social activities that may swirl about the Iba.

At left, the Head Mourner (Onye-isi-ozu) stands amidst the most prominently active group early this night. the Umu-Ilo (lit. “Children of the Village Square”), the male “youths” (unmarried) accompanied by some guiding elders. You can see some instruments of their quite substantial (and very accomplished) orchestra. At right, the Umu-Ilo proceed to march about the sub-village (guided by an elder, at far right), performing their songs.

At left, the Head Mourner (Onye-isi-ozu) stands amidst the most prominently active group early this night. the Umu-Ilo (lit. “Children of the Village Square”), the male “youths” (unmarried) accompanied by some guiding elders. You can see some instruments of their quite substantial (and very accomplished) orchestra. At right, the Umu-Ilo proceed to march about the sub-village (guided by an elder, at far right), performing their songs.

At left, a group of the Village Wives (Ikporo-ogbe, lit. “Village Women”) are performing their own dance at far left, to the tune of the senior woman’s metal gong. At right, an elder dances while the umu-ilo orchestra performs, now seated in front of the entryway into the Iba

The lineage Daughters (umu-ada) of the deceased remain inside the Iba with the igbudu throughout the night. At one point, they are joined by male elders, who play instruments and sing with them, but the Daughters will remain there overnight. At right, two of them are preparing for sleep beside a wife’s kitchen.

While I never have an opportunity to watch the process of burying the Igbudu and its sacred materials at the site of burial within an Iba, I do manage to see a subsequent ritual, which culminates the Lamentation process in relation to the grave (ini). My good friend T.C. Ikemefuna of Umu-Orezeabo, Umudei Village, invites me to observe the “Rubbing of the Grave” (itu-ini) of his father. Below left, you see Ikena standing in front of his father’s Iba. Second, he is seated on his father’s throne and holding his father’s Ozo title fan (as a mourner, he can do this, though in 1961Ikena is untitled). This is one of the smaller traditional-type iba I deal with while in Onitsha, but it has all the basic features. Third, you see some native goats wandering about the Ani-ezi (with the sacred egbo tree in the Ani-Ezi foreground, blessed with its subconical clay mound marking the locus of regular ritual offerings). These goats are treated as welcome pets (but are also sometimes sacrificed in rituals). The fourth image shows two umu-ilo of UmuOrezeAbo preparing the gravesite for receiving its final sacrificial offering, as Ikena stands by, guiding their efforts.

Below, at left, Ikena’s senior brother Ononenyi, who is Ozo-titled, cuts a goat’s throat as the lads restrain it, thus allowing its first blood to fall on the grave as an offering to the deceased. Then in the second image the mass of the blood is saved into an iron kettle. The goat corpse is then taken out in front of the Iba, located directly at the site of Ilo-OrezeAbo7 , where its hair is thoroughly burned off while the mourners watch. Finally, Ononenyi conducts the division of the meat, portions of which will be quite widely distributed to all of the father’s kin who have a claim.

Detailed views of Ozi’s Iba

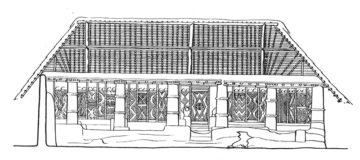

Soon after my earliest encounters with the great building, and the declaration of it as a National Museum, the Nigerian Government sendst an expert student of comparative architecture, a citizen of Poland named Zbigniew Dmochowski, to Onitsha as part of his wider tasks of recording the traditional forms of Nigeria. I escort him around various villages as he examines several traditional houses in Enu-Onicha (including of course the Ozi‘s Iba). Many years later, this remarkably talented man published his works on the architecture of various parts of southern Nigeria, and he included the Iba Ozi among them. ((See Dmochowski, Zbigniew, 1990, An Introduction to Nigerian Traditional Architecture. (Three Vols.) London: Ethnographical Ltd.)) Since in 1960-61he gratefully authorizes me to use his materials, I will present some of his drawings at relevant points, as here,

where Dumochowski drew a frontal image of Ozi’s house. This drawing shows the system of pillars that flank the entryway located slightly right of dead center. The carved wooden panels marking the front wall were presumably the work of Awka master craftsmen. Note the slightly flaring formal figure drawn at bottom just right of the stairway: this is the outlet of the Ulolo drain for the open atrium inside.

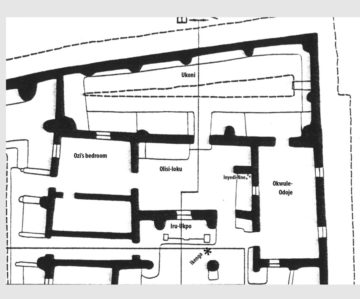

Now we have at right an overview of the whole structure of Ozi‘s house through Dmochowski’s layout. (The orientation here is roughly left-to-right = west-to east. ) This is not the basic form of the Iba (some examples of which we have already seen), but rather presents an elaboration, done for a man who has become a Chief (onye-iche).

The entryway to the typical Onicha Iba (“Ancestral House”) is typically called the Ogwa, though it may also be called Ibali in the case of a chief. The main, central chamber is called Ani-Ezi, “courtyard land”, typically with an Egbo tree standing as the central shrine (Newbouldia laevis, a sacred tree regarded as “age-mate of the land” and identified with the builder’s personal god). (I will deal with the features unlabeled on the right side of this courtyard diagram further below.) From the far end of Ani-Ezi, an entryway leads outward into a similar room called Agbala-Eze, “Servants of ‘exalted priest'”. This too has the courtyard structure, but this space is reserved for more private, intra-family, intra-descent-group matters, while the Ani-Ezi is used for more public — village, or  wider civic — events and topics. The Oba or “Barn” contains a series of vertical racks containing stored foodstuffs — yams, cocoyams, maize, other harvested goods.8

wider civic — events and topics. The Oba or “Barn” contains a series of vertical racks containing stored foodstuffs — yams, cocoyams, maize, other harvested goods.8

Note that flanking both sides of ani-ezi are spaces devoted (potentially) to four wives. These include both bedroom and kitchen for each.

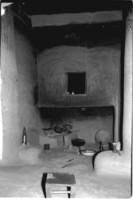

Below left, two views of wives bedrooms, showing clothing hanging above, the bed, and various trading items (stools, baskets, etc) below. Immediately adjacent is each wife’s kitchen (usokwu), which has a set of standard features. In the third image, you look directly into one particular kitchen, with its standard features: a tripod of stones. with firewood emplaced; directly above it, a smoke-oven (anuru); at lower left is a small adobe pen for fowl. The fourth image shows a somewhat larger kitchen, and you can tell from the presence of the ulolo, the atrium drain at bottom right, that this kitchen is located directly to the right as one enters the Iba. The pen for fowl is located just above it, and atop that is a platform for grinding-stone et al.

Below left, another view of a kitchen, here showing the akpata (shelves) at left, where the traditional pottery plates, bowls, and cups were stored on the shelving above, with water pots and mortars below. Then observe, in the second image, a closeup of a feature nearly invisible to the casual observer: a sacred shrine dedicated to the “Mothers” of this particular wife. Technically, this particular form is not quite standard; the typical Oma-nne shrine takes the form of a fully rounded mound toward the left, followed by a diminishing series that fades gradually toward nothing. The farthest-right photo below here (drawn from another kitchen in the Ozi’s house) shows it, but the image is so poor many may not be able to make it out (the left-curving crescent-line scratch is a photo-blemish just to its left). Every wife brings such a shrine to her marital home (though it may take somewhat different forms), dedicated to the maternal sources of her identity.

Turning now to the right-hand side of Dumochowski’s plan-diagram, focusing on Ani-Ezi and beyond, here for convenience I shift the orientation 90 degrees counterclockwise, so we start with the upper portion of Ani-Ezi at the bottom.

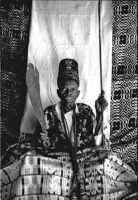

From a viewpoint at the base we look upward toward Iru-Ukpo, the “Face of the throne”. The pair of rectangular blocks linked by a horizontal line in the figure at right is Dmochowski’s icon for this location, indicating a portable support-structure that can be set up in front of the throne (ukpo) where the Senior Priest sits when a ritual is undertaken, and typically removed when it is finished. Ozi’s Ikenga figure is located close to the left side of the Throne, but as you can see in the series of photos shown further below, it is so completely covered with the residues of past ritual offerings that the type-figure cannot be seen at all. (Contrast Ezekwazili’s Ikenga shown beside his throne in the images above.) Note there is dried blood at the foot of the throne in the left-hand image below, showing that some sacrifice has recently been made directly before it. Also shown below, our hosts bring the Ozi himself out to sit for photographs on his throne, after he has been dressed and suitable cloth decorations have been added to the scene. 9

Referring again to the diagram, immediately behind the Throne room lies a ritually hidden room that is distinctly constructed for protection, from fire and from improper entry. This room is called Olisi-loku (or ofili), a “treasure-storage” room. Traditionally, it was said that the senior son of the head of this household was forbidden entry to this room during the lifetime of that senior priest. In Ozi’s room, we photographed the following features:10

At left, entering the room from the main hall, to the right near the entryway lie a set of fired-clay mounds dedicated to his “mothers” (the array is labelled inyedi-nne, “bringing in mother”). The symbolic importance of these links to maternal ancestries may be estimated by their size and visual prominence together with evidence of sacrificial gifts associated with them. This shrine links the Ozi to relatives through his maternal line, and is obviously an important aspect of his identity (and that of other members of this house). At right is a substantial alcove containing a number of important ritual objects, including a feathered fan (a special ritual fan) hanging on the wall. Just to the left of it is his chieftain’s ritual bag (akpa). Some metallic staffs are just visible at lower right. Behind the ekwe drum stands an array of ossissi (staves owned by Ozo-titled men). The drum is typically held by a chief for summoning people of the village — presumably the Ozi uses it primarily to summon his sub-village in Odoje.

At left, entering the room from the main hall, to the right near the entryway lie a set of fired-clay mounds dedicated to his “mothers” (the array is labelled inyedi-nne, “bringing in mother”). The symbolic importance of these links to maternal ancestries may be estimated by their size and visual prominence together with evidence of sacrificial gifts associated with them. This shrine links the Ozi to relatives through his maternal line, and is obviously an important aspect of his identity (and that of other members of this house). At right is a substantial alcove containing a number of important ritual objects, including a feathered fan (a special ritual fan) hanging on the wall. Just to the left of it is his chieftain’s ritual bag (akpa). Some metallic staffs are just visible at lower right. Behind the ekwe drum stands an array of ossissi (staves owned by Ozo-titled men). The drum is typically held by a chief for summoning people of the village — presumably the Ozi uses it primarily to summon his sub-village in Odoje.

Looking closer, at left you see (middle-right in the photo) the Ozi’s okwachi (the Personal God of an Ozo-titled man, bathed as always in white clay so long as he lives), this sitting atop two Okpulukpu (“housing” for two of his close titled paternal ancestors) and behind these, two pairs of ossissi (presumably those of the Ozi himself together with those of his father?). Just left of the ossissi, pinned on the wall, is the string-array used to hold ossissi when a ritual is performed at iru-ukpo. In the image at right, we move closer into this alcove. I did not obtain details regarding these objects, but the metal staff at the top is masquerade (mmanwu)-related. I was told that one box contained a cylindrical wood icon of untitled (and unnamed) ancestors — ndi-mmuo, the ghosts. Regarding the “boat-shaped” object in the center of the image: this was entirely unfamiliar to me in 1960s Onitsha, but I did see something that looked comparable —

Looking closer, at left you see (middle-right in the photo) the Ozi’s okwachi (the Personal God of an Ozo-titled man, bathed as always in white clay so long as he lives), this sitting atop two Okpulukpu (“housing” for two of his close titled paternal ancestors) and behind these, two pairs of ossissi (presumably those of the Ozi himself together with those of his father?). Just left of the ossissi, pinned on the wall, is the string-array used to hold ossissi when a ritual is performed at iru-ukpo. In the image at right, we move closer into this alcove. I did not obtain details regarding these objects, but the metal staff at the top is masquerade (mmanwu)-related. I was told that one box contained a cylindrical wood icon of untitled (and unnamed) ancestors — ndi-mmuo, the ghosts. Regarding the “boat-shaped” object in the center of the image: this was entirely unfamiliar to me in 1960s Onitsha, but I did see something that looked comparable —

far south from Onitsha in the Delta coast at Opobo, where in December 1961 we witness ritual persons carrying fire-smoking boat-like objects on their heads during the holidays there. I suspect, (but fail to inquire), that this object may have similar ritual uses.

Two more rooms are labeled in Dumochowski’s plan of the spaces behind Iru-Ukpo: the ukoni , the chief’s (or a “King”s) sanctified kitchen, a place where historically the sanctified household head would eat alone, of food prepared only by prepubertal boys. 11 I have one photograph of this space, but have misplaced it. In the Ozi’s house, it is almost entirely empty and I do not believe it is currently being used.

Secondly, what I have labeled the “Okwule-odoje” (though it might represent only a sub-section of that village), a secret room where ritual involving very hidden ritual activities may be undertaken and the necessary paraphernalia are kept. I think the image at left is taken in this location, but am uncertain. The large Medicine bundle in the mid-background is a remarkable feature. But the two objects at bottom right suggest to me patrilineage connections rather than masquerade per se.

At left, we now look into the Agbala-Eze from the perspective of the entry (shown in the diagram at right as the bottom of the vertical line marked “C”). You see in the center an egbo tree. flanked by pots and bowls indicating the relevance of ritual processes. I should say here that, as it turns out, I never have the opportunity to look closely or ask questions about the features of this part of the building, except for the presence of the shrine objects called Umu-ada. I do not manage to return and investigate further, so further details are lost.

At left, we now look into the Agbala-Eze from the perspective of the entry (shown in the diagram at right as the bottom of the vertical line marked “C”). You see in the center an egbo tree. flanked by pots and bowls indicating the relevance of ritual processes. I should say here that, as it turns out, I never have the opportunity to look closely or ask questions about the features of this part of the building, except for the presence of the shrine objects called Umu-ada. I do not manage to return and investigate further, so further details are lost.

Below left, my guide at the time of this visit, Akunne Matthew Uwechia, stands at left, and I believe the man right of him is one of the Ozi’s sons, here standing in front of the egbo tree . At his left grows a substantial taro plant. I never saw this in any other iba that I visited in Onitsha; taro (Colocasia esculenta) is symbolically distinctly a female’s plant12. Toward the right stand a pair of tall vertical poles, clearly of ritual import. The image below-center displays the large metal-enclosed shrine fixture, obviously very important, whose significance I entirely fail to identify. Below right you see the rounded clay mounds by the entryway, dedicated to The Daughters of the descent group (umu-ada), the bottles and white-clay chalk-marks indicating recent ritual offerings to them. Taken together with the ndi-nne shrines shown above, these mounded shrine objects clearly indicate the indispensable importance of linkages through women — mothers, sisters, daughters — for weaving together,regulating, stabilizing community affairs: in short, for maintaining the strengths of Onitsha society. Obviously, the Agbala-eze is a very important locus of the Ozi’s ritual life.

This concludes my observations regarding the Onitsha Iba. One additional image seems appropriate

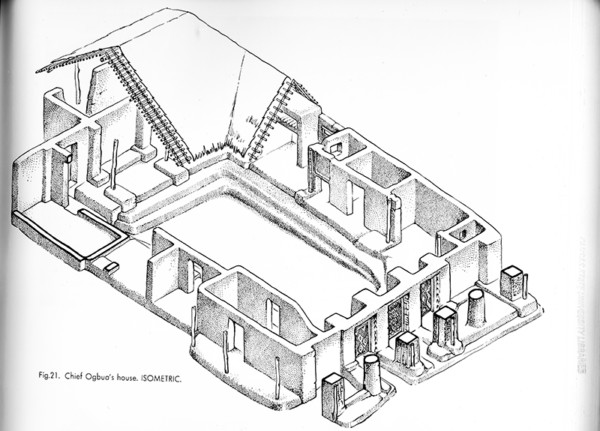

Dmochowski’s isometric drawing of the iba of Chief Ogbua gives a very nice sense of what these marvelous buildings are like to move about, both outside and within.

A Historical puzzle: Crowther’s 1857 account of “Onitsha housing”

In his initial survey of Onitsha Inland town, Ajai Crowther observed:

“Houses are very inferior here: they are mere enclosed verandahs, in oblong squares of mud walls, without rooms. After diligent search, we fixed upon one small square, which needed much alteration to make it habitable for any length of time.” (until our own place is built. Its loaction in the uplands was the reason for choosing this poor building. ” At another point he emphasizes that “The native houses here are mere sheds or verandahs, and afford no safe shelter for any length of time”, emphasizing that we need better accommodation to receive visitors from the interior.”

These observations impose upon us a requirement for reconciliation. Either Crowther seiously misjudged onitsha housing in 1857, or the qualities of that housing underwent very considerable elaboration during the subsequent century. I am inclined to believe the latter: a later passage from the CMS records, from 1883 during the “blockade of Onitsha” when the missionaries had moved their attentions to the town of Obosi, one report — CMS Int. & Rec. 1883: At Obotsi: most efforts of 1882 spent there; Cannibals, but their town is neater than Onitsha, houses better built have partitions and rooms, while at Onitsha simply enclosure within an enclosure, without separate apartments. (693 6). Josiah Obianwu went there for service. George Anyaegbunam interpreter. “The people of Obotshi appear more intelligent, thoughtful, and likely to take impressions than the people of Onitsha.”

This looks like a corroboration, but I will leave this issue for others to explore. A fuller history of housing practices among the Western Igbo-speaking populace would be a useful place to exploare.

- For details, see Henderson 1972, which covers the subject more fully than most readers will want to learn. [↩]

- Unfortunately this image is badly scratched horizontally across the surface. I initially tried having my film developed locally, but after seeing how cavalierly it was treated by a local “Photo Shop”, I sent all later film to London for processing. These were processed as accurately as the current technology allowed. [↩]

- Ezekwezili himself can be seen here at far left, performing an early phase of the annual harvest festival. [↩]

- 1962:25. [↩]

- I use this term in place of the anthropological convention of “age-set” because NdiOnicha used this term when translating their Ogbo into English. [↩]

- The disproportion in numbers between men and women in their fifties in Onitsha is due to the fact that so many Ndi-Onichamales have government jobs “abroad”. [↩]

- Note here the “motherly” presence of the mounded omumu shrine, devoted to increasing the descent group’s childbirths, together with the banana trees thought to draw both human and spirit children into the ilo. [↩]

- I neglected to photograph the Ozi‘s Oba, but see the example at left, which shows how the produce (in this particular case, cassava roots) is stacked. This particular Oba is quite different from the Ozi’s: located in Onicha bushfarmland, it is much larger, contains mainly cassava, and is protected only by fencing; the Ozi’s is walled and holds a diversity of harvest, primarily yams. [↩]

- I cannot resist reporting how we encountered Umera the Ozi on this occasion. (He was 90 years old at the time.) We were escorted into his bedroom (shown on the Dmochowski diagram here), and I am unsure whether he was sleeping in the room so marked or in the smaller one shown just below it. But we found him wrapped up in a fetal position, and the kinsman who escorted us “unpacked” him, so to speak, sat him up and dusted him off. In later years, when I chanced to see the comedic movie “Cat Ballou”, where the hero Lee Marvin first appears when he is “unpacked” from the rear trunk of a just-arrived stage-coach, I had the stunning memory of this improbable event. [↩]

- I must add here a caveat for any future students of the Henderson-Onitsha archive: while in Onitsha, at some point I made a map-drawing of the house — I think it must have been quite a while after my last visit — which, after carefully examining my photographs together with Dmochowski’s plan, indicate that the map contains some kind of serious error. My solution here was to discard the details of this map. [↩]

- See Henderson 1972:283). [↩]

- See Henderson 1972:159-62 [↩]