[Note: Click on any image you may want to enlarge.]

When I next spoke with Byron Maduegbuna, he voiced the opinion that the Enugu campaign pursued by the supporters of Onyejekwe had sufficiently influenced both the Eastern Nigerian Government and the various news agencies that Government was no longer likely to give quick recognition to Enwezor. Another factor he saw working in the favor of the Royal Clan Conference was the prospect of gaining the commitment of the non royal Umu-Ase to bestow their Ofo on Onyejekwe.

1. The prospects of support from Umu-Ase-Iyawu

Byron described the recent effectiveness of the Conference’s tactic of distributing among the IUmu-Ase-Iyawu many copies of the secret written promise the Prime Minister had made to the late Obi Okosi (that he would not support his own people in advancing their sectional claims), accompanied by careful exposition of Enwezor’s tactics and aims. The evidence of this document had aroused many of them against the Onowu, and Byron now affirmed that the Umu-Ase overwhelmingly supported Onyejekwe.

My own information on this village (drawn from ethnographic work there in the company of Mike Agbakoba) suggested that, aside from the chiefs and a handful of important senior elders, Umu-Ase opinion was much as Byron said. This was quite remarkable in view of the apparently great popularity the Onowu had enjoyed prior to committing himself openly to Enwezor. A group of their leaders had formally warned him not to make a decision on the kingship which might estrange them from him, and the village youths I heard voicing opinions in non political situations spoke openly against Enwezor.

In addition, Byron had a very important ally in the person of Omodi Nzekwu, the uncrowned Eze-Idi (Hidden King) of Obampkpa clan, with whom Isiokwe people held a Mother’s People/Daughter’s child relationship and with whom they had long cultivated deep loyalties. The fact that the March Agreement among the Umu-Ase-Iyawu had conferred the control of the Royal Ofo into the Omodi‘s hands made his position pivotal, and he was now working with the Royal Clan Conference (and with Akunne Oranye, one of his allies in Umu-Ase and father of Onyejekwe’s wife) to build support for Onyejekwe inside the group.

At this time, however, the issue of public support had become immediate, and the Umu-Ase-Iyawu were being pressured to make their formal commitment now. And although those supporting Enwezor were a minority, they included such influential elders as their three invested Ndichie (the Onowu, the Oduah, and the Asagwali) and two important senior elders, Akunne J.N. Offiah (an Onitsha Customary Court Judge who was the senior priest of Okwulinye segment) and Akunne J.A. Ifeajuna (a former Treasurer of the Onitsha Urban County Council who was a powerful elder of Okwugbele subdivision in Ogbaba segment).

(Genealogical chart here somewhere?)

The first public evidence of an absence of unity appeared in a report in the Spokesman of November 30 under the headline “Ofor for Onyejekwe”, describing a letter sent to Nzekwu the Omodi in his capacity as head of Umu-Ase-Iyawu from Mr. J. Onuora, an untitled elder from Odiegwu sub family (the subdivision of Ogbaba segment which had in traditional times held the right to confer the Royal ofo on the new Obi). In this letter (which was copied to both “H.R.H. J.O. Onyejekwe” and to “The Secretary Umuezechima Committee Meeting”) Mr. Onuora seemed to accept as factual a forthcoming presentation of the ofo to Onyejekwe, but he rejected the Umu-Ase-Iyawu Agreement of March, 1961, which had given the right of bestowing the ofo to the Omodi.1 He insisted that “the right to confer the Ofor on any Obi elect of Onitsha is in the port folio of Mr. J.A. Adaka who is the head of Ogbaba, Odiegwu, and Anumudu families of Umu-Ase, and must not be usurped by any living soul because of wealth and dignity so far he is alife (sic).” He called on the whole group to “come together and perform our duty” by giving Mr. Adaka his right and making an effort to recover the old ofo which Adaka had bestowed on the late Obi Okosi II.

This letter briefly exposed a facet of internal opposition to the recent Agreement signed among the Umu-Ase-Iyawu. The publication stimulated a flurry of letters from other elders of Umu-Ase, including one from an Enwezor supporter who claimed that the Family had no plans for bestowing the Ofo and one from a supporter of the Omodi who claimed that the right to bestow the Ofo had actually rotated among the Family’s major segments during the nineteenth century. I knew in fact that the Royal Clan Conference was trying to mediate the dispute by arranging for the traditionally rightful holder, Mr. Adaka, to return from his residence in Lagos and play his historically appropriate role together with the Omodi, but that this effort had failed. Now the pressure of events was forcing the Umu-Ase-Iyawu to make a less than consensual decision.

2. Disposition of the ancient “Anvil Ofo” (Ofo-Otutu)

Obiekwe Aniweta used the publication of these Umu-Ase letters as a basis for giving public justification for a prospective course of action by Enwezor’s group. In a Spokesman article published on December 2, he observed that the Umu-Ase “village has collapsed like a house of cards”, and recounted evidence of disagreement and “confusion… as to the rightful family to confer the ‘Ofor’ authority”, opining that

“There has been an organised conspiracy to overthrow the leadership while the followership is still confused. But it is not too late to retreat. The only avenue of escape is to accept the genuine leadership of Onowu Iyasele of Onitsha, Chief P.O. Anatogu… who has been doing his best to consolidate and systematise the ‘Ofor Institution’ of Onitsha and particularly that of his village, Umu-Ase.”

Aniweta then proceeded to recount the history of how “the ancient Kingdom of Umu-EzeAroli was challenged” and lost at the turn of this century, when Samuel Okosi of Oke-BuNabo was made King.

“Now the most important question is this: did Obi Samuel collect the Original and ancient Ofor from Obi Anazonwu? I emphatically say No. The Original Ofor still lies with Umu-EzeAroli people who refused bluntly to hand over these ‘Emblem of Authority’ to another ruling house.

Ofor-Eze-Aroli is therefore in tact here in the Ancient Kingdom of Umu-EzeAroli. Personally I don’t think it is necessary to hand over any other ‘Ofor’ to His Highness Enwezor I who already is in possession of the ‘Sacred and ancient Ofor’ of King Aroli Anazonwu.”

Thus after emphasizing the disunity among the non-royal Umu-Ase in claiming their right to bestow the Royal Ofo, Aniweta struck a final blow: the proposition that Umu-EzeAroli do not need non royal support anyway (except for that of the Onowu). And on the very day this article appeared, without any public announcements, the heads of umu-EzeAroli who supported Enwezor gathered at Enwezor’s house and bestowed upon him the two ancient royal ofo which Umera Anazonwu had brought from his family compound. The ritual was given but vague newspaper reporting, and only in the Observer which however strongly trumpeted its significance on December 4:

“NEW ONITSHA OBI NOW GIVEN ‘OFOR’

Dynasty Returns to Umu-EzeAroli”.

On December 9 however both the Observer and the Spokesman printed a letter written to the former by Dr. A.C. Anazonwu (an Epidemiological Specialist in charge of the Rural Health Headquarters, Oji River), saying,

“I have been directed by Akunne Joseph Agulefo Anazonwu, the present head of Anazonwu family of Ogbe-Ozala quarters in Onitsha, to refer to the publication [of December 4]…. Akunne Joseph Agulefo Anazonwu wishes to make it abundantly clear… that at no time was he consulted about, let alone acceding or otherwise to the removal of the Original ‘Ofor’ that belong to the Umu-EzeAroli family and which was used last by his late father Obi Anazonwu I, from the Iba (Ancestral House) of the Anazonwu family.

He wishes to stress his utter amazement at the current allegation that the ‘Ofor’ has been given to one of the contestants to the Obiship of Onitsha allegedly with his knowledge and endorsement of the act. He was, at no time, aware of any preparation for, and/or ceremonies connected with the alleged handing over of this ‘Ofor’.

Finally, he states that he will greatly appreciate it if the present recipient would disclose to the people of Onitsha the means, which appears now to be shrouded in mystery, by which he came to be in possession. He holds the view that the ceremony of presentation of Ofor to an Obi of Onitsha is a solemn one that should not be clothed in a ‘hush hush’ atmosphere.”

This sense of secrecy was expressed by others who commented about the action, and I felt it myself. While I was invited to attend the ritual dancing by the chiefs in Igwe Enwezor’s home courtyard on December 3, I was not even informed about the Ofo presentation of the previous day.

3. Egwu-Ota at Iba Enwezor

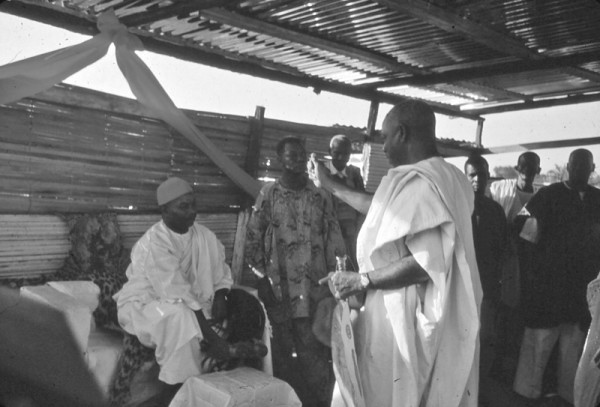

The December 3 dance ritual, also unpublicized and quite brief, was attended by about 70 of his close supporters. When I arrived, preparations were well advanced for a festive occasion.

I brought along my Wollensak tape recorder, and was photographed by an agent of Rex Studio.

At right, Igwe‘s courtyard was newly-decorated with many hanging cloths. Note here central-image toward the back, the ritual place occupied by those who stand as Di-Okpala to the host (Mother’s People, etc), now examining drinks being laid out for them as a group.

At right, Igwe‘s courtyard was newly-decorated with many hanging cloths. Note here central-image toward the back, the ritual place occupied by those who stand as Di-Okpala to the host (Mother’s People, etc), now examining drinks being laid out for them as a group.

The public event here was limited to expositions of the Royal War Dance (egwu ota).

Umera Anazonwu, now a highly visible figure in the courtyard, performed the chief’s dance as the war drums were played by an elder seated on the floor to the right of Enwezor’s throne. He (like the children I also saw doing the dance) conducted it in a formally correct manner, with synchronized movements of arms and legs, first using the right leg as a pivot while circling clockwise and then reversing both pivot and direction, marking closely the rhythms of the drum. The chiefs then entered the court, richly robed and carrying their leather fans but bareheaded, and Enwezor entered the room from his private chambers to the right. Sitting on his throne, dressed in white with feathered red cap, he was first saluted by the chiefs in the traditional manner, and then the chiefs began to dance in reverse order of seniority.

Umera Anazonwu, now a highly visible figure in the courtyard, performed the chief’s dance as the war drums were played by an elder seated on the floor to the right of Enwezor’s throne. He (like the children I also saw doing the dance) conducted it in a formally correct manner, with synchronized movements of arms and legs, first using the right leg as a pivot while circling clockwise and then reversing both pivot and direction, marking closely the rhythms of the drum. The chiefs then entered the court, richly robed and carrying their leather fans but bareheaded, and Enwezor entered the room from his private chambers to the right. Sitting on his throne, dressed in white with feathered red cap, he was first saluted by the chiefs in the traditional manner, and then the chiefs began to dance in reverse order of seniority.

The Eseagba, one of the oldest men in Onitsha and the most junior chief present, enacted a rigorously traditional version (his joints creaking audibly as he worked). The Odua, who followed, seemed scarcely to dance.

The Owelle, Onya, and Odu did recognizable if somewhat wandering, very modestly executed versions. At the conclusion of each dance the performer held his leather fan out horizontally above the altar, and Igwe Enwezor slapped the fan with his Ceremonial Sword (twice for the lesser chiefs, three times for the senior ones). In each instance the actions expressed mutual commitment between the parties.

The Owelle, Onya, and Odu did recognizable if somewhat wandering, very modestly executed versions. At the conclusion of each dance the performer held his leather fan out horizontally above the altar, and Igwe Enwezor slapped the fan with his Ceremonial Sword (twice for the lesser chiefs, three times for the senior ones). In each instance the actions expressed mutual commitment between the parties.

Finally, the Onowu emerged, wildly cheered by  the congregation. Wearing a gown that matched the color of his coral necklaces, he smilingly tied up his wrapper with exaggerated movements, then stood, holding his huge fan in his right hand, rocking slightly foreward and back, closed his eyes, puffed out his lower lip with a frown, and began nodding his head with a jerking punctuation while waving his left arm up and down in front of his face. The crowd erupted with cheers and laughter. Suddenly he took long bouncing steps, while both arms flopped about in apparent awkwardness, then stopped, turned, surveyed the crowd with an extremely deep frown. His eyes then closed, the jerking motions began again, and the sequence was repeated. I was astonished, but nobody else seemed at all perplexed. People expressed much amusement and delight.

the congregation. Wearing a gown that matched the color of his coral necklaces, he smilingly tied up his wrapper with exaggerated movements, then stood, holding his huge fan in his right hand, rocking slightly foreward and back, closed his eyes, puffed out his lower lip with a frown, and began nodding his head with a jerking punctuation while waving his left arm up and down in front of his face. The crowd erupted with cheers and laughter. Suddenly he took long bouncing steps, while both arms flopped about in apparent awkwardness, then stopped, turned, surveyed the crowd with an extremely deep frown. His eyes then closed, the jerking motions began again, and the sequence was repeated. I was astonished, but nobody else seemed at all perplexed. People expressed much amusement and delight.

Later I asked T.C. Ikena, one of the most traditionally knowledgable Onitsha men, about these patterns in the chiefs’ dancing, suggesting that most of the Senior Chiefs made at best mediocre renditions of the traditional form. He agreed that they were technically not very good, but pointed out that most of them had spent much of their lives in Western occupational pursuits, some located outside Onitsha. When I singled out the Prime Minister’s mode of dancing, Ikena mimicked it and laughed. “It is not real Egwuota,” he said, “it is just his art, his own style.”

I then suggested (myself assuming very much a purist-traditional stance at the time) that it seemed to me he was ridiculing the whole tradition of chiefly dancing, but Ikena defended the Onowu‘s right to develop his own version of the style. “It is just a dance there is no meaning in it. Why should he not create his own artistry?” To the extent I was able to explore the matter, his views were typical, and I realized more clearly that the Prime Minister was a very popular man, so much so that he might well convert a comical parody of this kind into something admired, a style which might in time become a new standard of performance.

3. The Umu-Ase-Iyawu vote, and its consequences

Shortly after Aniweta’s article was published and Enwezor acquired the ancient Anazonwu Ofo, leaders of Umu-Ase-Iyawu scheduled their voting in accordance with the provision of their March Agreement, which stated that “In the case of disagreement… the families shall each elect by ballot one candidate… and … in a general meeting… the Ofo shall be conferred by the majority of the five families….”2 On December 4 the Omodi sent letters to all senior priests of the Clan, directing them to hold their respective elections and then to convene at his house on December 6 to make the final majority decision. Akunne Offiah, as head of Okwulinye segment, refused to conduct its election, and Akunne Ifeajuna refused to bring his Okwugbele subdivision of Ogbaba segment to the latter’s voting, but otherwise members of the four participating segments met on December 6 in the house of their respective senior priests, and (according to the Spokesman‘s report on December 8) “In three of the four families Obi Onyejekwe had 100 per cent of the votes cast, and in one family he had 44 out of 45 votes cast….”

In a town famous for its manifold internal schisms, this was a truly noteworthy result. To what extent it was due to the immediately preceding behavior of Enwezor’s group in bypassing their traditional Ofo-bestowingprerogative, to the effective campaigning of Omodi Nzekwu and Akunne Oranye with the aid of the Royal Clan Conference, or to the charisma of Onyejekwe, was hard to assess. But the result was a stinging rebuke to the Onowu, whose social popularity did not translate into political results indeed, his own Ogbo Family (headed by the Omodi) had thus decisively rejected his leadership. Letters written by the two dissenting elders, Akunne Offiah and Akunne Ifeajuna, were later published in both local newspapers3, each expressing the opinion that the Umu-Ase-Iyawu‘s Ofo eze should be withheld until Government recognized a successor), but since both their names were listed as signatories to the March Agreement (and since they were known Enwezor supporters) the weight of their dissent seemed less telling than it might otherwise have been.

4. Dedicating an Ofo-Eze for Onyejekwe

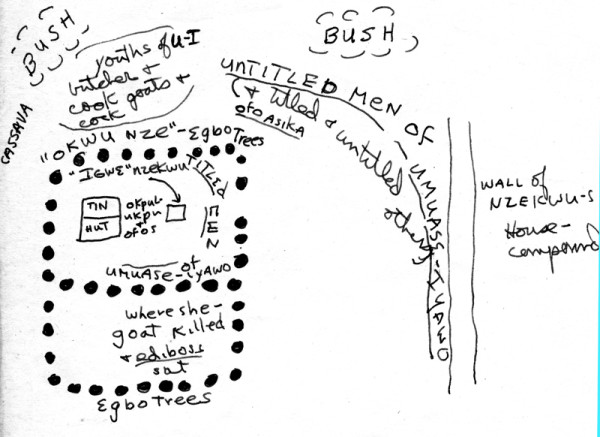

On December 8, I arrived at the Omodi‘s compact, cement block house on Oguta Road very near to the Onowu‘s, where the Royal Ofo was being dedicated for Onyejekwe. Seated on the porch, Mrs. Nzekwu directed me “to Nze,” pointing to the left around the side of the house. There, just outside the wall of Nzekwu’s compound, was the Sacred Grove of Nze (okwu nze) and its associated Square (ilo), where about 50 men and youths had gathered for the ritual.

To the right near the wall, in the Square, the untitled men and youths of Children of Ase Iyawu, and in the center a mix of titled and untitled men from other groups were congregated.

To the right near the wall, in the Square, the untitled men and youths of Children of Ase Iyawu, and in the center a mix of titled and untitled men from other groups were congregated.

To the left, the Sacred Grove formed an open rectangle bounded by /egbo/ trees and divided through the middle by a row of trees, so that two distinct inner sancta were formed.

To the left, the Sacred Grove formed an open rectangle bounded by /egbo/ trees and divided through the middle by a row of trees, so that two distinct inner sancta were formed.

In the sanctum on the far side, seated on a low goatskin covered stool facing the miniature tin hut which ordinarily contained the Nze objects, Nzekwu Omodi (clad in white singlet and wrapper) directed the rituals, flanked around by fellow Ozo men of Umu-Ase-Iyawu who were seated on goatskins on the ground. To his right sat the other senior priests (Di-okpala) of Umu-Ase-Iyawu (Akunne Offiah was absent, but a representative from his Okwulinye segment was there in his place).

In the sanctum on the far side, seated on a low goatskin covered stool facing the miniature tin hut which ordinarily contained the Nze objects, Nzekwu Omodi (clad in white singlet and wrapper) directed the rituals, flanked around by fellow Ozo men of Umu-Ase-Iyawu who were seated on goatskins on the ground. To his right sat the other senior priests (Di-okpala) of Umu-Ase-Iyawu (Akunne Offiah was absent, but a representative from his Okwulinye segment was there in his place).

In the sanctum on the near side, Akunne Ediboss sat on a folding chair, acting in his capacity as one of Onyejekwe’s two official representatives to the ritual. The second, Ofo Asika, sat on the ground of the square with myself and other visiting men. (Mr. Asika later told me with some indignation that Ediboss did not belong in the privileged sanctuary space, but “the bloody fool!”, he said, had insisted on separating himself from the others present, as befitted a superior person closely associated with the new Obi.)

In the sanctum on the near side, Akunne Ediboss sat on a folding chair, acting in his capacity as one of Onyejekwe’s two official representatives to the ritual. The second, Ofo Asika, sat on the ground of the square with myself and other visiting men. (Mr. Asika later told me with some indignation that Ediboss did not belong in the privileged sanctuary space, but “the bloody fool!”, he said, had insisted on separating himself from the others present, as befitted a superior person closely associated with the new Obi.)

The Nze itself was a complex formed by a pair of Okpulukpu, Ancestral Treasure Boxes (and their secret contents), on top of which was placed a very large (forearm length) ofo stick with a massive heavily medicine-bundled knob, alongside which was placed a bundle of nine small (finger sized) ofo sticks. These objects had been drawn out to a position in front of their hut for ritual invocation, and Igwe Onyejekwe’s newly fabricated Ofo-eze was placed on the ground to the right of and beside this complex. Bottles of beer, stout, a bottle of schnapps, and a jug of palm wine flanked the ritual objects.

The Nze itself was a complex formed by a pair of Okpulukpu, Ancestral Treasure Boxes (and their secret contents), on top of which was placed a very large (forearm length) ofo stick with a massive heavily medicine-bundled knob, alongside which was placed a bundle of nine small (finger sized) ofo sticks. These objects had been drawn out to a position in front of their hut for ritual invocation, and Igwe Onyejekwe’s newly fabricated Ofo-eze was placed on the ground to the right of and beside this complex. Bottles of beer, stout, a bottle of schnapps, and a jug of palm wine flanked the ritual objects.

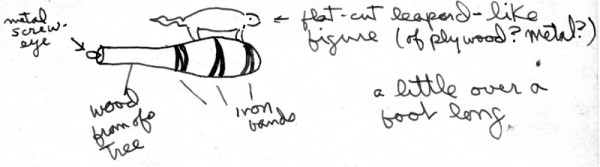

This Ofo eze was a staff of ofo wood about a man’s forearm (12″ or so) in length which thickened from its handle end 1/2″ in circumference to a roughly 8″ long swelling toward the other end that reached 2 1/2″ in circumference at its mid point. It had been painted a bright red with some substance. Along the swollen part 3 iron bands had been placed about 2″ apart, and on its top side stood a flat cut metal quadrupedal figure representing either a leopard or a chameleon painted dark brown on one side and green on the other, and encaged with four small flanking pieces of metal. Harding 1963: 143 provided the precise measurements; I managed to obtain only a brief and non‑tactile view of these objects. The photograph above is what I got, along with the following hastily-drawn figure:

This Ofo eze was a staff of ofo wood about a man’s forearm (12″ or so) in length which thickened from its handle end 1/2″ in circumference to a roughly 8″ long swelling toward the other end that reached 2 1/2″ in circumference at its mid point. It had been painted a bright red with some substance. Along the swollen part 3 iron bands had been placed about 2″ apart, and on its top side stood a flat cut metal quadrupedal figure representing either a leopard or a chameleon painted dark brown on one side and green on the other, and encaged with four small flanking pieces of metal. Harding 1963: 143 provided the precise measurements; I managed to obtain only a brief and non‑tactile view of these objects. The photograph above is what I got, along with the following hastily-drawn figure:

The ritual of dedication followed the usual Ndi-Onicha sequence of offering kola nuts, palm wine, and schnapps, then killing fowl and goat. The food, drink, and animals were first presented by Onyejekwe’s agents, then by the Omodi to the Nze in sacrifice, then shared first to the agents, then to the titled men of Umu-Ase-Iyawu, then to the other outside titled men, and finally to the remaining participants. However, a distinctive feature in dedicating something to the Nze is the use at the very beginning of the ritual (even prior to offering kola) of a baby chick in the act of “calming the body” (iju aro). The Omodi lightly beat the chick around the body of the Ofo-eze to absorb any “heat” contaminating it, then split the beak of the animal and let its blood drip down on the Ofo-nze.

After kola and drinks had been offered to the Nze, a cock and a he-goat were presented to it and their throats were cut so the blood flowed upon the Nze objects and the Ofo-eze, and the remaining blood of the goat was collected in a pan into which the Omodi dipped his hands and rubbed onto the various ofo sticks before him. A female sheep presented for offering was however sacrificed separately in the other sanctum, and neither its blood nor its meat could enter the Nze sanctum proper. When I asked if any woman could step into the Okwu-Nze, the elders responded, “What? Never!”, and pointed out that no man could wear any cloth there which he had previously worn “going to a woman.” While cooking, the two types of soup were kept separate and the senior priest himself could partake of only the male type.4

The Omodi invited each of Onyejekwe’s agents into the Nze to kneel and receive the remainder of partly libated drinks from his hands (saluting him, “igwe”, in reply to his salutation), and I too was invited for a shot of Schnapps. Then, while several young men prepared the meat and cooked the soups (one a mixture of he-goat and cock, the other of the female sheep) , a man walked out from Nzekwu’s house carrying the red tail feather of a grey parrot (called /a’wumme/), which he took into the Nze and assisted the Omodi in affixing it to the Ofo-eze. (This feather represents the power of killing dangerous animals. Other feathers, which I was unable to detect, were also placed onto the Ofo at some other time.) Meanwhile, people sat and talked about football pools, national politics, rituals and dances scheduled elsewhere in the Inland Town, and the Obiship.

When the soups were ready, one youth carried that made of he goat and cock into the Sacred Grove of Nze, while another brought that of the female sheep among the men waiting outside the shrine. A third carried a large stack of enameled tin pans into the grove. After calling each of Onyejekwe’s representatives into the shrine to notify them of the next steps, the Omodi with the pot of soup to his right, took the great Ofo-Nze in his left hand and placed it over the Treasure Boxes (Okpulukpu), while holding the soup ladle in his right, and began praying to the ancestors while pouring soup over the Ofo. As two youths argued outside, one elder shouted to them, “Be quiet! They are begging the ghosts (igo-mmuo)!”

Then the Omodi held the cooked head and legs of the cock and offered them to the Treasure boxes, praying, “Ofo-Nze, this is the head and the leg of the cock offered to you by Joseph Onyejkekwe, the Obi-elect.” Then he placed them on top of the Treasure Boxes and called his senior son, who entered the shrine and took away the head and legs as his own special share. Then the Omodi called Akunne Ediboss, who was given a piece of goat meat as Onyejekwe’s share.

The most junior Ozo man inside the shrine, the “divisor”, began to ladle out equal shares of goat and cock soup into the 13 pans provided for the 13 men in the Nze sanctum, and at the same time 13 pans were being filled with sheep stew for the titled men outside the shrine. As the Ozo men received their shares, they immediately began calling youths to come and share their portions. More pans were then brought out, and the remainder of the people were served portions from both inside and outside the shrine. the people ate their food and soon began to disperse.

4. Presenting Ofo eze to Onyejekwe

During the day of the dedication, agents of the Royal Clan Conference distributed leaflets through the Inland Town which announced

. . . . .

“UMU-EZECHIMA (Kingmakers) of ONITSHA Inviting

All Citizens of Onitsha

to attend the Ceremony of the Presentation of Ofor,

(The traditional Staff of Office and the Symbol of

Authority and Divine Power) To His Highness J.O. Onyejekwe I

BY THE ENTIRE UMU-ASE-IYAWU FAMILIES OF UGWUNAOBAMKPA

OF ONITSHA, THE TRADITIONAL CUSTODIANS OF THE STAFF OF OFFICE (OFO)

OF ALL OBIS OF ONITSHA.

On Saturday 9th Dec. 1961 at 4. p.m. at Ime Obi (King’s Palace)

Ogbeozala Square Onitsha.

C O M E O N E ! ! C O M E A L L ! ! !

Come And Watch This Important Historic Event.

. . . . .

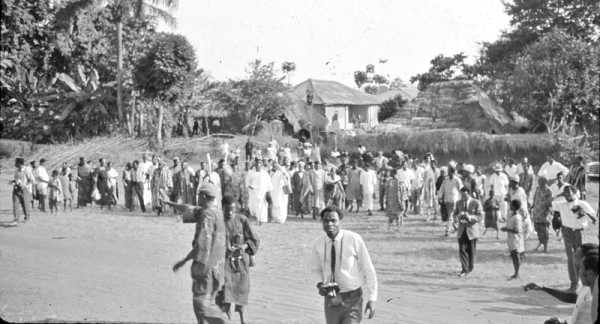

That Saturday afternoon, a crowd of elders and young men gathered before the house of Omodi Nzekwu in Umu-Ase Village. The Omodi and 14 other titled senior priests of Ugwu-NaObamkpa5 dressed in white gowns and white caps with eagle feathers, some carrying their ivory horns, led a procession of perhaps fifty men (including a small orchestra of village drummers) escorting the newly dedicated Ofo-eze through the streets of Umu-Ase and Ogbe-Ozala.

That Saturday afternoon, a crowd of elders and young men gathered before the house of Omodi Nzekwu in Umu-Ase Village. The Omodi and 14 other titled senior priests of Ugwu-NaObamkpa5 dressed in white gowns and white caps with eagle feathers, some carrying their ivory horns, led a procession of perhaps fifty men (including a small orchestra of village drummers) escorting the newly dedicated Ofo-eze through the streets of Umu-Ase and Ogbe-Ozala.

Igwe Onyejekwe, wearing a white gown and red cap and holding his black horse tail fly whisk (sign of both mourning and high title), began his own orchestrated procession from his house with about fifty men of Ogbe-Ozala (Akunne Ediboss flanking his left side and carrying an ivory horn). At the grounds of the temporary palace they were greeted by a gathering crowd mostly composed of Ndi-Onicha but also now including a substantial corps of photographers (the Conference having taken care to notify all representatives of the media).6

Igwe Onyejekwe, wearing a white gown and red cap and holding his black horse tail fly whisk (sign of both mourning and high title), began his own orchestrated procession from his house with about fifty men of Ogbe-Ozala (Akunne Ediboss flanking his left side and carrying an ivory horn). At the grounds of the temporary palace they were greeted by a gathering crowd mostly composed of Ndi-Onicha but also now including a substantial corps of photographers (the Conference having taken care to notify all representatives of the media).6

Onyejekwe strode up a dusty avenue cleared by the waiting crowd, and entered the palace.

Onyejekwe strode up a dusty avenue cleared by the waiting crowd, and entered the palace.

He sat on his leopardskin covered throne, holding the fly whisk in his left hand, his feet resting on a dais covered with gold-decorated black cloth. Before him on the dais was a low box covered with white cloth to serve as an altar. Akunne Ediboss, who had placed the ivory horn on the dais in front of the altar, now stood bare headed to the Igwe‘s left. Various bare-headed men entered the palace, knelt before Onyejekwe, and saluted him, Igwe, as they touched their heads to the ivory horn.

He sat on his leopardskin covered throne, holding the fly whisk in his left hand, his feet resting on a dais covered with gold-decorated black cloth. Before him on the dais was a low box covered with white cloth to serve as an altar. Akunne Ediboss, who had placed the ivory horn on the dais in front of the altar, now stood bare headed to the Igwe‘s left. Various bare-headed men entered the palace, knelt before Onyejekwe, and saluted him, Igwe, as they touched their heads to the ivory horn.

By the time the Umu-Ase-Iyawu procession arrived at the palace grounds, they were greeted by an enthusiastic crowd of more than a thousand well-wishers, and were saluted by the blowing of ivory horns (Okwu-Odu) and by cannon fire. Their orchestra entered the palace and, kneeling before Onyejekwe, played him a salute, while outside the senior priests prepared an arena before the palace stairs where the Ofo presentation could be made.7

By the time the Umu-Ase-Iyawu procession arrived at the palace grounds, they were greeted by an enthusiastic crowd of more than a thousand well-wishers, and were saluted by the blowing of ivory horns (Okwu-Odu) and by cannon fire. Their orchestra entered the palace and, kneeling before Onyejekwe, played him a salute, while outside the senior priests prepared an arena before the palace stairs where the Ofo presentation could be made.7

While the other priests of Umu-Ase-Iyawu removed their caps, they wrapped the Omodi‘s head with a broad band of white cloth, insignia of his Eze-idi (Hidden King) status. Flanked by his priests, he knelt before the stairs to the palace, addressed the Ofo-eze with prayers to his ancestors and to the former kings, then took the stick in his two hands and declared that on this day, I bestow upon you this Ofo-Eze, which according to Onitsha tradition is the exclusive right of my ancestors. May your reign be blessed with peace and prosperity. (The reader will note the press-photographer competition I was dealing with at this pivovtal moment. The chamedeon Icon on the Ofo-Eze is visible here, however.)

While the other priests of Umu-Ase-Iyawu removed their caps, they wrapped the Omodi‘s head with a broad band of white cloth, insignia of his Eze-idi (Hidden King) status. Flanked by his priests, he knelt before the stairs to the palace, addressed the Ofo-eze with prayers to his ancestors and to the former kings, then took the stick in his two hands and declared that on this day, I bestow upon you this Ofo-Eze, which according to Onitsha tradition is the exclusive right of my ancestors. May your reign be blessed with peace and prosperity. (The reader will note the press-photographer competition I was dealing with at this pivovtal moment. The chamedeon Icon on the Ofo-Eze is visible here, however.)

Then he entered the palace and, bending his knees before the throne, presented the staff with his right hand to Onyejekwe, who palmed it in both hands then took hold of it with his right. As men came forward to kneel and touch their heads on the altar, the now-formally Obi tapped the Ofo-eze on the altar in acknowledgement, returning their salute. The Ogene also came forward and presented the raised thumb greeting appropriate for those of Ndichie-Ume rank..

Then he entered the palace and, bending his knees before the throne, presented the staff with his right hand to Onyejekwe, who palmed it in both hands then took hold of it with his right. As men came forward to kneel and touch their heads on the altar, the now-formally Obi tapped the Ofo-eze on the altar in acknowledgement, returning their salute. The Ogene also came forward and presented the raised thumb greeting appropriate for those of Ndichie-Ume rank..

Outside, more cannons were fired, one shot generating a remarkable smoke ring which rose and expanded above the palace itself. Onyejekwe then stepped out of the palace and, escorted now by his red capped chiefs and most of the crowd, walked back to his house where refreshments were being served.

Outside, more cannons were fired, one shot generating a remarkable smoke ring which rose and expanded above the palace itself. Onyejekwe then stepped out of the palace and, escorted now by his red capped chiefs and most of the crowd, walked back to his house where refreshments were being served.  The Spokesman of December 11 reported the ritual under a banner headline, and inserted in a separate small headlined box the information that

The Spokesman of December 11 reported the ritual under a banner headline, and inserted in a separate small headlined box the information that

“Both the Press and private cameramen focussed their attention towards the sky at the Ime Obi of His Highness Obi Onyekekwe I to have a snapshot of a strange sign which featured during the presentation of the official ‘ofor’ symbol of kingly authority to the Obi, last Saturday.

The sign, which took the shape of a crown high up in the sky and diametrically above the palace where Obi Onyejekwe was seated, was quickly formed by smoke which sparked off from a cannon shot heralding the historic occasion.

Over the week end observers described the sign as ‘meaningful’.”

Enwezor’s people were not so impressed with the rituals, to judge by Obiekwe Aniweta’s release printed in the same issue of the Spokesman. He quoted a statement by the Onowu condemning the bestowal of an Ofo to Onyejekwe by “a negligible section of Umu-Ase Family,” and pointed out the fact that the three Umu-Ase chiefs and two senior elders (Offiah and Ifeajuna) had dissociated themselves from the action, while the village segments of these two elders, “the whole of Okwulinye (and of Okwugbele) family ridicules with the greatest contempt for a minority group in Umu-Ase to present Ofor to Mr. J.O. Onyejekwe.”

- ftnt: see Ch. 15 pp. 18 20. [↩]

- See Ch. , p. . The text of the Agreement was published in full in the Spokesman of December 7, 1961. [↩]

- Dec. 9, 1961. [↩]

- For the significance of Nze in Onitsha religion see Henderson 1972: 259 281, 307, 368 70. [↩]

- This included not only titled elders from Umu-Ase-IIyawu but also some from Odoje and Ogboli-Eke, other non-royal representatives.. [↩]

- This included Ughas, the well-known “Silver Medalist” Onitsha photographer, seen here in the foreground. [↩]

- The praise-singer shown here was part of the performing group, but exactly who he was I did not manage to determine. The white eye-mark is a ritual icon, but not used much by people in Onitsha Inland Town. [↩]