The osilike Age-grade of Onitdsha is composed of native Ndi-Onicha who were born between 1916 and 1918 (in 1962, aged in their forties). Among these membersof this “grade”1 was Jerry Orakwue, a person of some prominence (athough not a titled man) due partly to his perennially responsibe participaiton in community affairs and his profound knowledge of Onitsha “law and custom”2. Mr. Orakwue kindly invited me to witness a fellow member’s ritual of consecrating his new Ikenga, which I was delighted to do.

Unfortunately my field notes of this event appear to have disappeared without a trace, so I rely entirely on my memory together with the photographs I took of the occasion for this account. 3

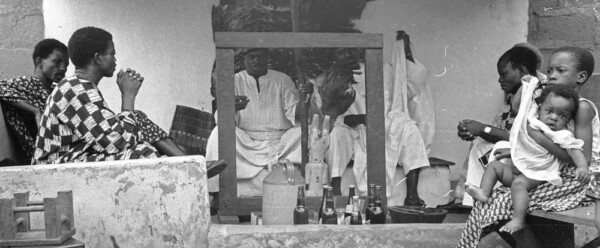

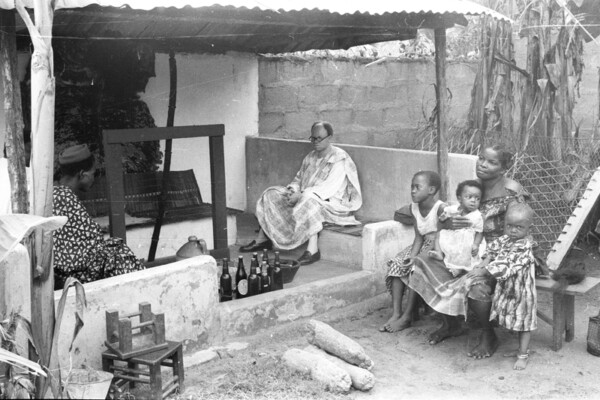

At left, you see, the (rain-protected) outdoor alter building of the priest who will conduct the ritual. Jerry Orakwue sits in center image, dressed in his finery. The priest’s wife sits outside the altar, holding her three children. Note the large guinea yams (dioscorea alata) placed at the foot of the entryway.

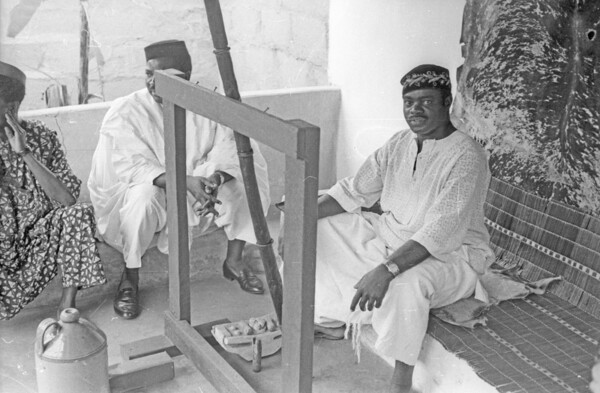

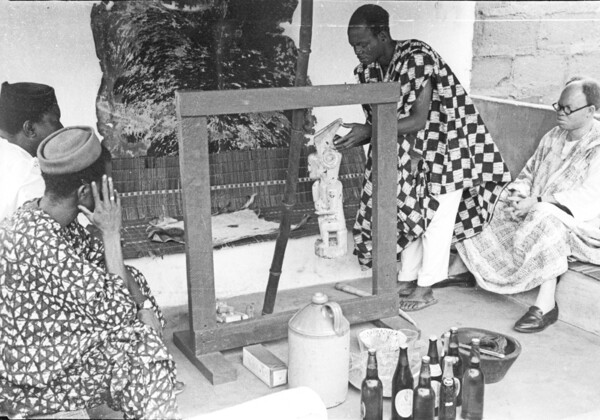

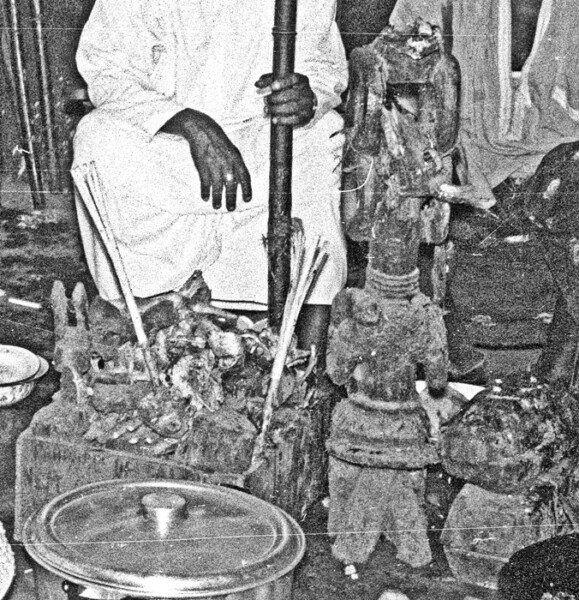

The priest has taken his seat at right, also dressed finery. He is Ozo–ttitled, as you can tell from the iron-ringed ossissi staff resting on the altar before him (a primary symbol of his ozo– priestly authority), the cow-leather tapestry behind him –indicating he is an Ogbuefi (“cow-killer”,) — and the goatskin on which he sits. His companion to his right is also titled, while the third man here is untitled (but also dressed in finery). Note more closely, then, the ritual object behind the altar framework, on the floor near the staff of office.

The white, boat-like object is the priest’s okwa-chi, the sacred emblem of his purified (ozo-titled) self. Next to it is much smaller object, his current ikenga (personal power source) . This is a very basic form of ikenga — very small, its cultural identification based solely on the indicator “pair of horns” shown at the top. I would think he obtained this icon when he “came of age”, and I would guess it has been with him for many years. He now proposes to exchange it for a larger, stronger one.

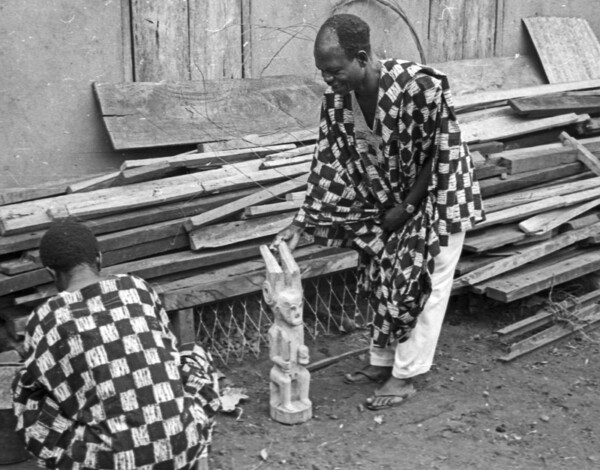

Two fellow age-mates have now brought out the new, replacement ikenga from a private room,, and are clearning it in preparation for presentation to the altar. All age-grades sharee among their members some kind of standard apparel, and I would guess that these two are wearing this type of dress to signal that membership. They treat the new ritual object with careful respect.

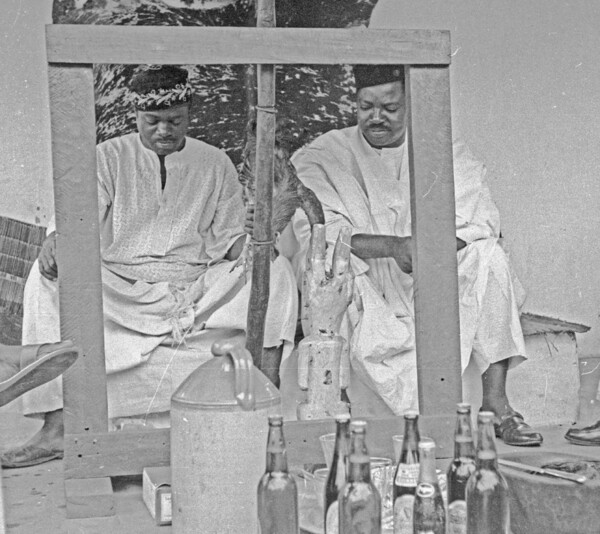

The replacement ikenga is carefully set at the altar. Note before the alter a small box containing Schiedham Schnapps (an Onitsha ritual offering highly favored by everyone), along with a large jug containing fresh palm wine.

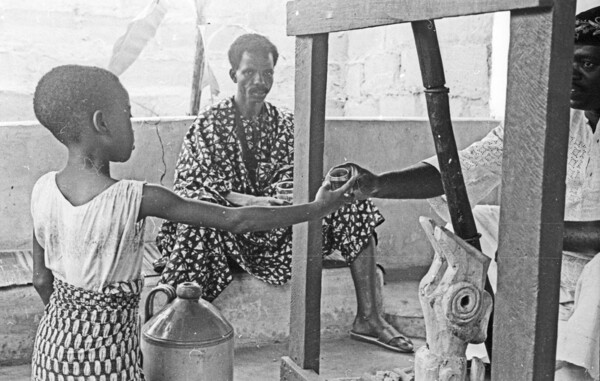

Here, the priest offers a cup of palm wine to his senior daughter (ada), signaling their very profound ritual relationship. The young girl already displays the grown-up poise shown by most Onitsha women who have reached the”age of sense”, in my experience.

Now the priest isj joined at the altar by his fellow ozo-man, who sits at his left acting as a cooperative guide. Holding a live cock in his left hand, the priest presents his affirmations, including appreciations of the cooperation of his fellow worshippers and his hopes and intentions for himself and them for the future.

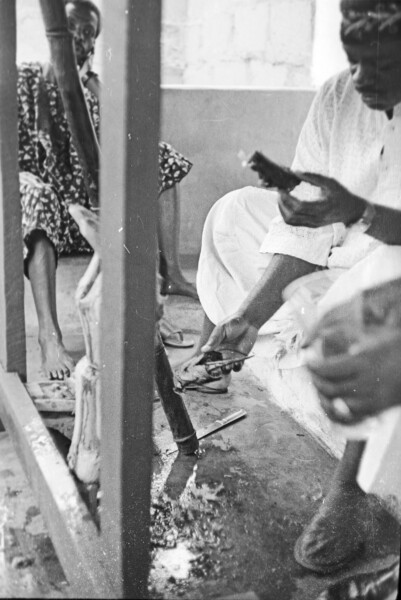

Then, holding the feet of his captive cock with his left hand, he cuts its throat with the knife held in his right, letting the blood flow down on the now-becoming-sanctified ikenga.

And here he is about to dispense with the old one. In some places in Igboland such figures are sometimes retained as parts of a ritual complex

On this occasion I did not wait around to join in the further festivities, but both other family members and other age-mates would be drawn into the boons of this ritual. , The Guinea Yams would be pounded into the stape foo-foo, The cock would be made into a stew, and palmwine, Guinness Stout, and other drinks would be widely dispensed.

Some varieties of Ikenga form

This particuar Ikenga at left was one of a group I seized out of the onrushing fiery furnace created by the RCM priest at Nnewi who was conducting an Anti-juju Crisade (See Chapter 5, the “Religion Matters!” pageathers’ Anti-juju Crusade””page).

It was so caked over with dried blood t from innumerable acts of sacrifice by its previous owner hat it was hard to recognize. (I scraped off the excess to view the essentials of the form.) This is a fairly basic form, though the “pipe” descending from the chin indigates it represets an ancestor of the holder. The body form — a cylinder indented toward the center — is a fairly common icon of a humanoid being’s body.

These all came from my Nnewi seizure. They range from realistic at left to very abstract at right. In the far left form, the horns rise as if out of a helmet, a common style.

This image is however in representational error: I must have scanned the film in reveres: the hand positions are rfalsely presented here. The correct reading is the right-hand holds the means of success (a knife), while the left-hand holds the rewards of effort (an “ivory horn”), symbol of wealth.. (In some styles, a figure of a human head represents the relevant accomplishment.)

The middle forms show standard variants of minimally representing a body.

This Ikenga at left hangs on my dining room wall. I bought it from a master Awka carver who was also selling carved stools for ozo-titled men, tables, etc, all very fine work. This figure exaggerates the horns into an elaborate helmet, and shows the High-achiever seated on a stool. The “means-and-ends” opposition of thie triumphant male’s arms are correctly rendered in this photograph.

At left, this was the largest kenga I saw at Onigtsha. It belonged to Omodi Nzekwu, a very prominent chief from Umuasele Village, who had set it out here while celebrating the Umato festival. We only see its back, but it sits on a title stool and its very high horns are massively entwined with the residues of past ritual performances. (Note that at far left in his box of Ndi-mmuo you can see a small Ikenga there. This presumably represents one of his ancestors.)

- The correct anthropological term is “set”, but Ndi-Onicha use the term “grade” and I follow their practice her.e. [↩]

- Some portion of which is embodied in his Onitsha Chapbook publication, Onitsha Custom of Title-Taking. [↩]

- The names and titles of the other participants have not been retained in my memory. [↩]