RITUAL ROLES OF WOMEN IN ONITSHA IBO SOCIETY

By Helen Kreider Henderson

Ph.D Dissertation Department of Anthropology, University of California (Berkeley) 1969, Copyright 1970 Helen K. Henderson

…………………………………………………………..

Editors’ Note: Helen never found time to revise her dissertation for wider publication. This was particularly unfortunate: it was immediately identified by her Thesis Advisor in 1969, Professor William Bascom, as “a feminist tract”, and it soon gained considerable attention among those anthropologists of the early 1970s who were actively opening that field of research soon to be called “Women’s Studies”, countering such male anthropologists’ stereotypes as “Women have no culture”. However, since it remained solely a microfilm text, her book never obtained the wider recognition it deserved.

And it has remained over the years in the somewhat rough form typical for dissertations published solely in microfilm. As her editors now preparing it here for a wider audience, I (Richard Henderson) and our son Michael Henderson have chosen to maintain all of her content and organization (though we have changed numbering of sections to make her many analytic divisions and subdivisions clearer for this text), and otherwise have largely restricted our efforts to correcting some typos and ambiguities of language. (We have not altered her use of “Ibo” for “Igbo“, the former being a term in conventional use at the time of her writing, now largely in abeyance.)

For the most part we have not tampered with the distinctly “objective” and passive-constructing “impersonal” style of authorship that was fashionable for most anthropologists at the time and which Helen carefully followed, but which today gives the text what seems to us a very stilted tone. (In a few places we did insert Helen’s voice a bit more than she allowed herself to do.)

One point should be emphasized to the unfamiliar reader, regarding her use of tenses in this work. In many passages, Helen writes in the present tense about customary procedures –” Onitsha women do so-and-so” — when these practices are no longer in operation, were matters of the past when we were studying in Onitsha, and even in some examples when they were past-tense early in the twentieth century. In much of the text, she uses this “ethnographic present”, or “traditional present”, often mixing this with reversions to the obvious past: “In 1857, Bishop Crowther observed that Onitsha women were conducting…..”. Her writings in this style concern “traditional culture”, what Onitsha people call “Odinani“, matters of the (Mother) Earth, or (in their own common English parlance in 1960) “Matters of Native Law and Custom”. The aim is to convey a social and cultural system of the past in way that does not tiresomely distance the reader from the activities being described. (And some of them do deserve a genuine present-tense, being still in operation today.)

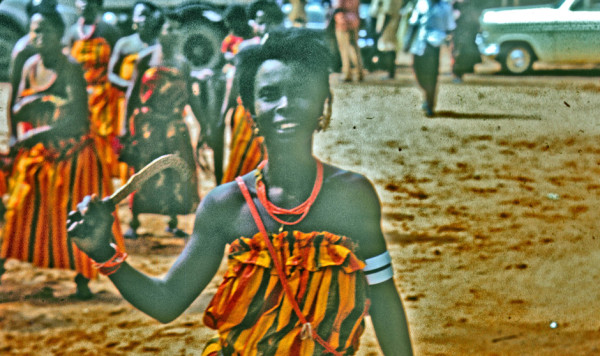

I (Richard) have taken the liberty of inserting images into her text where they seem usefully illustrative (mainly my own Onitsha photographs) and provide some links to other resources in this broader research.

……………………………………………………………

PREFACE

The field work upon which this dissertation is based was carried out in Onitsha, Nigeria in 1960-1962, under a grant from the Ford Foundation awarded to my husband, Richard N. Henderson, which enabled me to accompany him on his dissertation field research.

During the time we lived in Onitsha, it was a bustling commercial center which nonetheless contained a viable traditional core community with a King, chiefs, age sets, and strong popular interest in traditional culture. The model of Onitsha society and religion described here is that of Onitsha from shortly before its very intensive contact with the West to around the close of the 19th century, the latter being a period well documented by missionaries and other travelers. Informants’ accounts of past and recent events have also been relied upon heavily. The manifold activities of Onitsha women were quite striking, especially their funerary activities. The women’s organizations were remarkably dynamic, and appeared to have been so traditionally. The topic of this dissertation emerged after it became apparent that there was a lack of detailed information in the anthropological literature on women’s roles in African religion, especially data which identified women in their respective roles in the society – wife, mother, daughter, trader, etc.

It is hoped that this study will stimulate greater interest in the social-structural correlates of women’s religious activities, and in the symbolic systems concerning women in West Africa. Of the many people who have helped me in this research, my greatest debt is to the men and women of Onitsha who gave generously of their time and knowledge. It is deeply saddening to think of them now, since at the time of this writing [1969] most of them are refugees, the town of Onitsha itself having been substantially destroyed in the Nigeria-Biafra war. Among the Onitsha people who were of invaluable assistance to me were Mrs. Janet Okala, the late Madame Emembulu of Isiokwe village, the late Okunwa T. B. Akpom, T. C. Ikena, Akunne F. Oranye, and my field assistants, Harriet Ofodile, Matilda Emembolu, Grace Araka, Victor Umunna and Byron Maduegbunam. After our return to the United States, Mr. Umunna, who had come to this country to do Graduate work, gave invaluable assistance in organizing the funerary data into more coherent form. I am very grateful to Professor William Bascom for reading this manuscript over a period of years and for his criticisms and encouragement. Thanks are also due to Professor Herbert Blumer and Professor William Simmons for their reading and criticism of the manuscript.

My husband Richard has given me unending encouragement throughout the years of work on this dissertation. Mrs. Evelyn Middleton and Miss Ella Gibson produced the manuscript under rather difficult working conditions. A word should be added concerning certain idiosyncracies of the text. Capitalization has been used to remind the reader that a common English term has been given a somewhat distinctive meaning in translation from Ibo to English; e.g. Burial and Lamentation are capitalized as labeled ritual complexes; and Village Wives, Daughters of the Patrilineage etc. have been capitalized to avoid ambiguity and to indicate the corporate nature of the groups mentioned.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

RITUAL ROLES OF WOMEN IN ONITSHA IBO SOCIETY, By Helen Kreider Henderson. ©1970 by Helen K. Henderson

…………………………….

Editors’ Note: The Table of Contents is extended and quite complex. For example, Chapter One deals with anthropological theories regarding religion that were current during the late 1960s, a subject perhaps marginal to readers whose particular interests concern particular rituals of Igbo-speaking peoples. However, we recommend giving these materials some attention, because Helen’s treatment of these diverse perspectives remains valuable. The same is true of the rest of the work. Chapter Two places Onitsha in relation to wider West African culture, and this introduction will be valuable for anyone wanting to learn about varieties of religious experience encountered there. The same may be said regarding every chapter outlined below, and here we wish simply to emphasize: hidden within the labyrinths of these chapters is a masterpiece of ethnographic description and ethnological interpretation, some of it more detailed and comprehensive in its comparative examination of rituals than may be found anywhere else in the literature on West African religion.

We should note that the numerical listing of the contents differs considerably from the way Helen presented them in the Dissertation (with “a’s” and “b’s” as well as “1)’s” and “2)’s”), but not in overall substance. We have made these changes in order to clarify how she organized the sometimes very complex subject matter.

…………………………………………..

CHAPTER ONE: SOME PROBLEMS AND APPROACHES TO THE

ANTHROPOLOGICAL STUDY OF RELIGION

1.1. The Phenomenon of Religion: An Anthropological Definition

1.1.1. The Position of Jack Goody

1.1.2. The Position of Talcott Parsons

1,1,3. A Critique of Goody’s Position

1.1.4. Robin Horton’s Views on a Definition of Religious Development

1.1.5. The Position of Clifford Geertz

1.1.6. Assessment

1.2. Religion, Magic, and Witchcraft

1.2.1. Magic and Religion

1.2.2. The Problem of Witchcraft and Sorcery

1.3. Methodological Approaches to the Study of Religion

1.3.1 Some Social Structural Approaches to the Role of Women in Ritual

1.3.2. Some Unanswered Problems in Regard to Women and Religion

CHAPTER TWO: SOME ASPECTS OF WEST AFRICAN RELIGIOUS SYSTEMS

2.1. Some Prevalent Religious Themes

2.1.1. The Major Categories of Spiritual Forces

2.1.2. The High God

2.1.3. Spirits of Natural Features

2.1.4. Medicines

2.1.5. Ghosts of the Dead

2.1.6. Masquerades as Representations of Spirits

2.1.7. Destiny and Reincarnation in West Africa

2.1.8. Women’s Relations to Concepts of Destiny

2.1.9. Divination

2.2. An Outline of Onitsha Religious Beliefs

2.2.1. The Concepts of God and Destiny

2.2.2. The Ghosts of the Dead

2.2.3. Spirits of Natural Objects

2.2.4. Medicines

2.2.5. Summary

CHAPTER THREE: THE KINSHIP ROLES OF WOMEN

3.1. Ecological Setting and Historical Overview

3.1.1. Ecology

3.1.2. Historical Setting

3.2. Kinship/Descent Structures

3.2.1. Kinship Terminology

3.2.2. A Comparison of the Roles of Male and Female Members of the Patrilineal Descent Group

3.2.2.1. Boys

3.2.2.2. Girls

3.2.2.3. Decision-making among Adult Males of the Patrilineage

3.2.2.4. The Adult Daughter’s Role in the Patrilineage

3.2.3. Patterns of Marriage Arrangement

3.2.4. Marital Roles

3.2.5. Summary: Women’s Roles in Kinship and Descent Groups

3.2.5.1. Roles in the Natal Patrilineage

3.2.5.2. Roles Established through Marriage

3.2.5.3. Stabilizing Factors relating marriage and lineage systems

CHAPTER FOUR: STRUCTURALLY DIFFERENTIATED ORGANIZATIONS

4,1. The Village

4.1.1. Lineage Heterogeneity

4.1.2. The Role of the Chief

4.2. The Masquerade Society

4.2.1. Membership and Organizational Bases

4.2.2. The Character of Leadership

4.2.3. Major Functions of the Masquerade Society

4.2.4. The Position of Women in Regard to the Masquerades

4.3. The Age-Set System

4.3.1. Membership and Organizational Bases

4.3.2. The Ruling Age Set

4.3.3. Social Clubs

4.3.4. The Position of Women in Regard to the Age Sets and Social Clubs

4.4. Ozo Title System

4.4.1. Religious Basis and Membership Standards

4.4.2. The Relation of the Titled Man to Females

4.4.3. Special Honors Accorded Women

4.5. Chieftaincy and Kingship

4.5.1. The Organization of Chiefs

4.5.2. The King

4.5.2.1. Political and Religious Activities

4.5.2.2. Relations with Women

4.6. The Queen and Her Council

4.7. Some Extraordinary Women of Onitsha

4.8. Summary

CHAPTER FIVE: ONITSHA WOMEN AND RITUAL

PART 1: GENERAL RELIGIOUS RITES

5.1. Women and Prayer

5.1.1. The Kola Ceremony

5.1.2. Women’s Ritual Objects (Non-Seasonal Religious Activities)

5.2. Rituals Involving the Head Daughter

5.2.1. Adultery Confession

5.2.2. Dispute Settlement

5.2.3. Rituals Involving Deceased Famous Daughters

5.3. Rituals Performed by the Town Mothers

5.4. The Ceremonial Cycle

5.4.1. Ifejioku

5.4.2. Ajachi

5.4.3. Umuato

5.4.4. Owaji

5.4.5. Itu Ukpukpu

5.4.6. Osisi-ite

5.4.7. Iru Ani

5.4.8. Osekwulo

5.5. Negative Aspects of Women’s Ritual Power

5.5.1. The Daughter as Witch

5.5.2. The Wife/Mother as Witch

5.5.3. The Punishment of Witches

5.6. Supernatural Attack by Men

5.6.1. Ogboma

5.6.2. Sorcery (Ikunsi)

5.7. Summary: The significance of the autonomous ritual activities of women

5.7.1. Prayer

5.7.2. Ownership and Propitiation of Shrines

5.7.3. Roles played in the Ceremonial cycle

5.7.4. Witchcraft and other forms of supernatural attack

5.7.5. Ogboma and Ikunsi

CHAPTER SIX: ONITSHA WOMEN AND RITUAL

PART TWO: ONITSHA FUNERARY RITUAL Death (Onwu), Burial (Ini Ozu) and Lamentation (Ikwa Ozu)

6.1. Ideas Concerning Death

6.1.1. Death Concepts and Attitudes

6.1.2. Final Causes of Death

6.1.2.1. Predestined death

6.1.2.2. Violent death

6.1.2.3. Deaths caused by witchcraft or sorcery

6.1.2.4. Deaths caused by ancestors or spirits

6.2. Death and Burial

6.2.1. Overview of Onitsha Funerals

6.2.2. Announcement and Burial Rites for Men

6.2.2.1. For Titled Men

6.2.2.1.1. Announcement Sequences

6.2.2.1.2. Other Burial-day Activities

6.2.2.1.3. Pre-burial rites conducted by women

6.2.2.1.4. The Rites of actual Burial

6.2.2.1.5. Activities on the day after burial

6.2.2.2. Mourning restrictions

6.2.2.2. Burial Rites for an Untitled Man

6.2.3. Announcement and Burial Rites for Women

6.2.3.1. For Titled Women

6.2.3.1.1 Announcements, arrangements

6.2.3.1.2. Ceremonies prior to burial

6.2.3.1.3. Activities on the day after burial

6.2.3.1.4.Mourning Restrictions

6.2.3.2. For an Untitled woman

6.3. Summary: an overview of the burial process

6.4. The Lamentation

6.4.1. Indigenous Interpretations of the Meaning of the Ritual

6.4.2. Lamentation Rites for Men

6.4.2.1. For Titled Men

6.4.2.1.1 Preparations

6.4.2.1.2. The First Day

6.4.2.1.3. The Second Day

6.4.2.1.4. Days after Igbudu Burial

6.4.3. Lamentation Rites for Women

6.5. Summary of Lamentation Rites

CHAPTER SEVEN: CONCLUSIONS REGARDING ONITSHA

7.1. Major Religious Values Expressed in Funerals

7.1.1. The Personal God (Chi)

7.1.2. Ghosts of the Dead

7.1.3. Alusi

7.1.4. Medicines

7.2. Other Indicators of the Spiritual Status of Women as Expressed in Ritual

7.3. The Position of Women in Onitsha Social Structure

7.3.1. Ecological and Historical Factors

7.3.2. Rights and Duties of Women in their own Patrilineages

7.3.3. The Status of a Woman as Wife

7.3.4. Women as Community Representatives

7.3.5. The Problem of Witchcraft

CHAPTER EIGHT: WIDER COMPARATIVE CONCLUSIONS

8.1. Comparison Within the Ibo-Speaking Area

8.1.1. Asaba District Ibo

8.1.2. Central Ibo

8.1.2.1. Ritual Objects of Women

8.1.2.2. Daughters of the Patrilineage

8.1.2.3. Wives of the Patrilineage

8.1.2.4. The Role of Mother

8.1.2.5. Organization of Village Wives

8.1.2.6. Religious Activities of Village Wives

8.1.3. Afikpo Ibo

8.1.3.1. Overview

8.1.3.2. Women as Members of the Patrilineage

8.1.3.3. Women as Members of the Afikpo Matrilineal

8.1.3.4. Wives of the Patrilineage

8.1.3.5. Degree of incorporation of Wives in the Patrilineage

8.1.3.6. Divorce and Widowhood

8.1.3.7. Organization of Compound Wives

8.1.3.8. Non-Kin-recruited Associations in the Village

8.1.3.8.1. Age Sets

8.1.3.8.2. The Men’s Secret Society

8.1.3.9. Summary

8.2. The Yoruba: Some Comparative Remarks

8.2.1. Overview

8.2.2. Women as Members of the Patrilineage

8.2.3. Marriage

8.2.4. Women in the Community

8.2.5. Witchcraft

8.3. Conclusion

………………………………………………………….