[Note: Click on any image you may want to enlarge.]

(Note: the original version of my essay was presented at the University of Arizona School of Anthropology Symposium held in Helen’s honor September 8, 2017. Many thanks to Diane Austin who organized it all, and to everyone who participated. I subsequently added a few footnotes where these seem appropriate, and I have since added some further reflections where they seem to be relevant. RNH, June 2019)

My aim here, aside from honoring a wonderful human being now departed, is to shed light on matters of gender, a central political problem of our time — from the far reaches of the globe right down to this room. We live in a world where some people still think that menstruating women give off dangerous toxic fumes — “bleeding in their whatevers” is one obvious example of an egregious comment by one of the worst exemplars of sexist thinking in our time [Donald Trump] — that menstrual blood can drive away thunderstorms, that sex with a virgin can cure a man’s STDs; that a raped, unwilling woman can’t get pregnant; that if pregnant women have bad thoughts, these will ruin their babies; that women can’t, or maybe just shouldn’t, think too much – it makes them angry and infertile. These are just a small sample; we live in a world where sociopolitical policies and practices still find strong grounds in such nonsense, and all of this — beliefs, policies, practices — must change.

I will also venture some guesses about how Helen’s and my own “experiential feminisms” developed over our years together. (Some readers have questioned my rather unusual treatment of pronouns in this essay, shifting from first to third person, etc. Prior to undertaking the necessary memory-research for writing all this, I read a very interesting recent book, The Voices Within: the History and Science of How We Talk to Ourselves (Charles Fernyhough, author ), which made the point that talking to oneself has rather different emotional involvements depending on which pronouns one employs during the process. I found that for my own self-history work of this kind, thinking about this, and moving around in my pronominal references, helped lessen the pain incurred during this kind of memory work.)

I will not discuss Helen’s career at BARA 1. Here I explore her deeper history, how she came to be her BARA persona. How did Helen become the BARA “babe” we knew in the 1980s and 90s: strong scholar/organizer pursuing needs and goals of “Women in Development”? She didn’t start there: 1950s undergraduate Helen told close friends at Syracuse University that her main life’s ambition was to “marry an anthropologist and go to Africa”.

My over-view of the “how” question is, in general: she learned to build strong balance between seeking greater freedoms of action — along the distinctively feminist lines of expanding social cooperation — and the necessary corollary of freedom: increasing one’s capacities for Impulse control.

I propose Eight “Phases”, knowing if Helen were present here today, she’d likely just demolish it with a witty reposte (then, hopefully, we could talk about it some more).

Phase One: “Limited prospects” (Harrisburg, PA)

Strong family patriarchy: her Pennsylvania-German father’s father would de-self his wife — “Quiet, Woman!”, he’d say when she tried to speak socially — but this harsh family culture moderated when Helen was born:

She came late to The Kreiders of Harrisburg, in 1936; (Homer and Nita had feared they would never have children; 40-year-old Nita’s father-in-law (the patriarch), a homeopathic doctor, insisted Nita merely had “a floating kidney”, but Helen’s birth disconfirmed this hypothesis.)

Helen’s mother Nita — now doing her designated life’s-work as mother — conformed to the ethics of Kreider House , but also ran deep-closet resistance to male power, aided by her own loving mother who lived just blocks away. (Nita definitely had “blithe spirits” lurking inside — see the undated image at right, which she labeled “A Duck”.) These two women helped Helen escape the worst de-selfings of Pennsylvania German patriarchy, forging Helen’s creative, “actor” side — One of Nita’s (only slightly realized) ambitions was to do eccentric things: for example, she would amuse her husband’s colleagues and their wives at parties by playing the role of a gypsy fortune-teller .

Helen’s father Homer, only son of the patriarch, a lawyer (later Judge), moved somewhat beyond his father’s views; he and his best friend would enjoy evenings talking “real-politique”, and when Helen reached “the age of sense” (here we’re looking somewhat later, to her teens), they let her entertain them by mocking national political figures. One memorable act was to don her father’s suit-jacket and walk downstairs for her “Dwight Eisenhower Press Conference”, aping the great man’s way of avoiding Press Corps questions by deploying elaborately meandering speech.).

So within this “patriarchy” (And throughout her father’s lifetime to some extent) it was an odd fact that her mother did not teach her manual skills. Nita’s social class standards, and her methods of deception toward males, worked to fix Helen’s gender categories. (I think Nita was caught up in some version of the “Feminine Mystique”. A graduate student who met Helen’s mother briefly in New Haven referred to her as a “Painted lady” — Nita elaborately constructed her face before entering the public eye.) Nita also told Helen, “Don’t let any man know that you can type!” Some sterling deceptions were a striking feature of this upbringing.

Her “Katherine Sweeney Day School”

was Co-ed at primary levels, girls-only at puberty, aiming to place girls in good colleges. Helen acted in plays, avoided teenage “sex-games”, learned French and “serious subjects”. The school was near the Kreider house, so Helen would “host” her friends there. She enlarged her cooperative circles — but within a mainly gender-restricted frame.

Her mother drove a car — not well, but actively , but never taught Helen to drive, which seems curious. Was she overprotective? This was definitely a disadvantage for Helen in later years: (I eventually helped her learn to drive in Tucson, but she did not do it well; fortunately, nobody was physically hurt in any of her numerous driving accidents. )

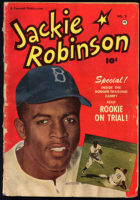

More mysterious, but very important: someone in the Katherine Sweeney Day School inspired Helen to “identify with” an American Black man now becoming a Major-league Baseball super-star. When Jackie Robinson broke the League’s color barrier in 1947, Helen plunged into her first (if virtual) love affair: she created private rituals to help the Brooklyn Dodgers win, then convinced her mother to take her all the way to Ebbets Field in Brooklyn, where she could cheer her hero in public. (That’s Helen’s own desparing “end of season” cartoon at above right.)

This major gain in freedom — both in thought and action –could work because her everyday behavior was mostly impeccable. This was a very unlikely “first-love”-engagement for a middle-class white girl in the late 1940s to early 1950s: a strong “skewing of consciousness” away from her family. Her father, and most other relatives, were quite openly, unapologetically racist, and shocked by this “craze” Helen had fallen into, but her mother trusted, hence actively supported her daughter. In 1954, when one of her Freshman college roommates (eventually a life-long friend, named Ruth Ginsberg) visited the family while these rituals continued, Helen’s father took her aside and expressed his worry — this strangeness, what “mental disorders” may his wife and daughter be suffering?

Phase Two: Syracuse Anthropology and Learning

1)) She Avoided Sororities:

(I have no content inforamtion regarding this, but it was surely decisive — sororoities were dedicated to molding thougt and action into narrow grooves of socfially conformist style.)

At Syracuse in 1954, Helen joined rooming houses, built life-long friendships with diverse, intellectually challenging women. Her social relationships proliferated. For example, she briefly palled around a bit with future award-winning novelist Joyce Carol Oates — they would ditch P.E. together –, and while Helen spoke of writing her own “Great American Novel”, Joyce Carol actually did just that (more than once).

(2) In introductory anthropology,

(2) In introductory anthropology,

She read Bronislaw Malinowski, who explained the social-and-psychological functions of those magical rituals Helen had been doing to help the Dodgers. Grasping these powerful insights propelled her into this major, and to say she would “marry an anthropologist and go to Africa.” Not a full feminist, at this point but her perspectives greatly widened through these kinds of experiences.. (Some might sneer at such talk a bit in the years 2000s, but for her at the time this meant forging some new long-term goals. )

3) Helen was “swept off her feet”

by a graduate student in psychology, tall, handsome, articulate, clever, overt breaker of “social conventions”. (When Helen questioned his hitting the gin bottle while driving his VW bug — tossing the empties out on the streets as he went — he replied “because driving is so boring”.) Engaging, except in intimate social interactions, where his view was purely “What’s in this for ME?” He openly bragged of “consuming” eager female bodies (He drew for her a quite sophisticated cartoon, displaying himself as a “Yogurth Beast” eating his way through a crowd of “shmoo-like” beings, all of them hopping-ready to be chewed alive into his gut.), and soon jilted Helen, departing to northern New York State as a high-school psychologist (a career that would of course put him in contact with many prospective objects of desire).

Heartbroken Helen applied to Anthropology graduate schools, accepted at Berkeley spring 1958, when the recent-jilter called her long-distance: one of his female students was now pregnant, so would Helen please marry him right away! Helen replied, “I’m going to Berkeley”, hung up the phone. Her room-mate, seeing her distraught, said, “Why don’t you just go up there and marry him?”; Helen bawled, “He’s not good enough for me!”

Obviously, she took a definitely proto-feminist step here. “putting down” her feelings, focused instead on interpersonal commitment, and she never recontacted this person, though for a time she retained that “Yogurth Beast” cartoon — she later showed it to me. He also appeared on the national news a few times, as a fringe New-Age Guru, and eventually “came out” as a Holocaust-Denier. (His name was Arthur Kleps — you can look him up on Wikipedia, though the entry seems extremely sketchy, almost perfunctory. He spent time at the MillBrook estate with Timothy Leary, associated with psychedelic activists during the 1960s, founded his own psychedelic Church, etc.)

Phase Three: A Team Forms at Berkeley

Arriving there late August 1958, one of the first people Helen met was me.

Dick was,

Compared with her previous male attachment, I appeared also bright perhaps but quiet, courteous, friendly, interested, cautious with other people. I had learned that considering female wants was imperative in intimate-social situations — note the qualifiers ( I still had much more to learn, but at least I was a strong contrast with the Yogurth Beast).

Educational Skills:

Helen’s Syracuse gave good general grounding, but my New Mexico graduate training was much stronger, in light of what we now encountered at Berkeley (New Mexico in 1958 had provided a link to Harvard’s Department of Social Relations, then-new integrator of social and behavioral sciences. Harry Basehart arrived at UNM with a Harvard Ph.D. in 1955; he was also deeply invested in research on African societies and cultures, and as his student I was committed both to going there and to this “newly systematic social science”..

Helen and I now entered a new-theory dynamo — David Schneider, Robert Murphy, Lloyd Fallers and Clifford Geertz came together. . I was ready for them; Helen, not so much — she needed some assistance at first,and I much enjoyed acting . (I also had a decent grounding in linguistics, which Helen lacked and which she did not get even at Berkeley, which had a separate Linguistics Department. This weakness remained a limitation for her in all her fieldwork.).

We became Co-Residents,

each of us taking a room in the same “Berkeley Shingle” rooming house. (This was a redwood-shingle-sided house with a redwood-tree-yarded, 3-storey building containing a mix of male and female students and former-student hangers-on. People on each floor shared bathrooms, and on my second-floor we shared a kitchen as well. Helen moved into the third floor and had her own kitchen. )

We grew close walking to school together, talking science, sharing food, and by Christmas sharing love: I had never met anyone like her – open, socially outgoing, excited to explore ideas – morally alert, witty in ways both startling and endearing. The only odd thing I noticed, she bit her fingernails down to the nub. She perhaps thought I “Knew Everything”, and I seemed a gentle, friendly person. We both actively sought to please the other. (One way we did this was to go camping. On one long trip into the Marble Mountains of Northern California, Helen spoke with passion about our “primitive” moments together. (But secretly she regarded these ventures as rather a chore.)

Working together — We co-participated in seminars, in which I starred while she first found hardship. Our two introductory seminars illustrate this: (1) an innovative, very sophisticated seminar co-taught by the prominent sociologist Reinhard Bendix (Max-Weber-oriented) and anthropologist Lloyd (“Tom”) Fallers (closely linked to Africanist British social anthropology), this seminar examining the grand subject of the History of Social thought, and (2) in another context we both took a seminar on hominid evolution co-taught by an elder Theodore McCown and then young-buck Sherburn Washburn (he full of startling new ideas and knowledge on that subject). We both fell into these tsunamis of ideas, but Helen was in far more danger of drowning than I was. Helen was not ready for the History of Social Thought seminar; however, she gained real respect when she wrote a paper for the hominid evolution seminar, on the subject of human “cold adaptation”, which showed she could do original research – this one could have been published in the Kroeber Anthropology Papers, it was that new and cogent.). We both established ourselves in the Department by Spring 1959. I applied for a Ford Foundation Research Grant. We married in August, received at the home of Professor Schneider. It looked like Helen would meet her goal: she had married an anthropologist, and we two would go to Africa!

Phase Four: Troubles in Paradise

The “Honeymoon”

I Think I decided what we would do — drive out camping along coastal California. Helen complied. (But I later learned she never cared much for camping. Her motives for the earlier enthusiasms seem dubious. I think that while courting she used some subtle tactics learned from her mother — see Phase 1-A. In later years, we camped a few times; in all these other cases I think the social bonding made the (often uncomfortable) effort seem worthwhile to her.) We went to a campground on the coast, pitched our tent and settled in for the night. It had rained a bit. A stray kitten entered our tent: it was coughing, obviously sick. Helen wanted to keep it (she loved cats). I was allergic to cats at the time, and I must have just said, No. No memory of this conversation, but I was adamant the cat had to go. (Indeed, I rose and escorted it well across the campground, where I left it to its fate.)

Next morning, Helen, now silent, pensive, said to me, “Will we be happy?” She seemed much more distant as we drove further up the coast. Guessing her viewpoint at that moment: a late-1950s version of “Am I stuck here in patriarchy once more?” Dick’s learning here, nil beyond “I guess she’s realizing marriage is a big step for her.”

A recent New York Times essay put the situation well in general terms:

“Strong Man” Collapses

In the first half of this phase, Helen may have learned not to idealize any male. In the second half, she confronted more serious shortcomings of this particular version of that gender.

In this altered frame of view, Helen next had the opportunity to see her new spouse enter full psychological-academic collapse in the fall of 1959 (due to my carelessness in navigating complex intra-departmental politics).

The Department of Antrhopology at Berkelely was in one sense split in two parts at the time, and I carelessly and totally attached myself to the avante-garde side. A member of the other side struck bacck (because I had ignored him mainly outg of shyness) , and my response was total psychological collapse. I was helped through the collapse by all parties concenred — everyone must have been shocked by this totality. But the Department as then structured did not last — the avante-garde partners departed to other univsities soon afterward.

………………………….

Helen stood by me in this moment (and I should add, so did others in my student cohort who witnessed the events) , but — in light of my now-obvious flaws, a Ph.D. of her own must have now became a strong goal — definitely a step toward real “feminism”. (A standard mantra of Helen’s was “Character is fate” — a revealing comment about what people can (or maybe can’t) do about what may befall them — and she clearly had a sense of what her own character should be.

Dick’s learning from this phase remained too deeply painful to conduct a careful systematic analysis, but the experience was damaging for some years to come. I lost some verbal interactive skills, for example, sometimes experienced a kind of aphasia looking for obvious words to finish a sentence (an experience new to me at the time, definitely perplexing). To make a blunt assessment (at a distance of more than 60 years), I think I suffered a mini-stroke of some kind.

Despite the collapse, I won a Ford Foundation grant to go to Africa to study “A City in Transition”. This came directly from the voice of the great political scientist James Coleman, who smilingly said to me, “Why don’t you go to Onitsha? They say it’s split right down the middle!”. (I may have been given the grant because they sensed that a pair of people would be doing it; Helen would help stabilize my somewhat compromized condition).) 2, which shows the power of psychedelics as psychotherapy. This was how I experienced them, more than fifty years ago. (Looking backward, my problem in using them concerned dosage: the “hits” I enjoyed should have been divided up into much smaller amounts, taken much more rarely.)

Beverly Seckinger, our UA anthroological film-maker, has just finished her film on “Hippy Family Values”, which I recommend to you all.

By Spring in 1968, Helen was pregnant.

blooming out in many ways. At one class — these are held for new parents to prepare for childbirth– Helen, far advanced by this time, asks me, “Are those others as big as I am?” Yes, I reply (though they aren’t, not nearly). Later, as she’s examined by her main doctor, he observes bruskly, “Too Many Limbs”; she is X-rayed, then he cryptically states, “Two complete fetal skeletons.” This was definitely a “Doctor of Few Words”, but also competent in his job.

Helen also “bloomed” in warmth, calm, and energy in these times. and when twin sons Kevin and Michael were born February 7, 1969, both parents were magically transformed. (Into loving ones — major social-psychological changes, I will not talk about here).

They arrived home a week later, to a letter from Berkeley: “Submit your completed dissertation by the end of May, or you will be permanently dropped from our Program!” This concentrated our minds, and we both mobilized. By the end of May her completed dissertation was mailed to Berkeley, she went there, defended it, her thesis advisor, William Bascom, commented: “This is a Feminist Tract.” We both wondered what he meant, but now returned to the other distractions absorbing our lives.

“The Feminist Tract”:

See further below here, in this page’s “Appendix”, for more details. I will simply say, the entire work is a tour-de-force comparing Igbo women’s differing ways and means of access to political power during the early historical period. (She even briefly considered the Yoruba. In all these cases she asked what factors appear to favor political weakness in one domain, for example (Collective Wives), strengths in another (lineage Daughters), and so on. Helen’s work received strong positive reception in major universities along the eastern corridor, but so focused were each of us elsewhere at the time that we just “let it go”. This was a serious loss to the new field of feminist publications. It could have been published with modest editing, as you see it here in Chapter 9.)

From 1969 to 1971, the grand flood of activities

carried us along many pathways. Helen and I organized a Relief Fund for Biafran Children and I organized both protests on campus against Federal Policies toward the Biafra War, and a symposium offering prominent speakers on the topic. Stanley Diamond and I tried to organize anthropologists, but this effort failed. I also provided substantial research materials to a student group at Yale wanting to research the issue, but “their house burned down”, along with the documents inside it. Both Helen and I took part in workshops and marches against the Vietnam War, which intensified through all our remaining years at Yale. I helped monitor massive, potentially explosive demonstrations on campus. Helen worked locally in support of anti-war candidates, and she went to The March on Washington in 1967, riding in June Nash’s car. June Nash, one of the earliest and strongest true feminists I met in those days, sometimes extended herself so much that she forgot “trivial things”, to her misfortune. On this occasion, June had forgotten to update her vehicle registration when a D.C. policeman stopped her car; she and Helen ended up at a police station where a fine was assessed, but neither Helen nor June had thought to bring money with them. June was bound for Jail until Helen remembered a friend in Bethesda who she called and who came promptly providing the necessary bail. This was just one episode in a grand avalanche of Henderson Follies during that time.

In 1971, Dick was denied tenure at Yale.

I job-searched. Prospects near the East Coast were inviting, but these required me becoming Chair of Department, jobs that, I knew, I simply could not do. I wanted to go somewhere calmer. So I flew to New Mexico and Arizona for interviews.

My attachments to the West have always been profound. All of my roots were in the West: Mountain Wyoming, from the Tetons and Yellowstone to the Bighorns, Powder River, North Platte and many other Rivers; the southwestern deserts from Utah to Mohave-California; Coastal California; the uplands of New Mexico. I loved them all, and never felt close to the East. Seeing the Arizona Uplands of the Sonoran Desert around the University of Arizona, and the people working in UA Anthro at the time, enchanted me. I leapt at an offer of a tenured full-professorship from Arizona.

And here is a mystery: how did Helen and I discuss why I couldn’t stay East? I think I hardly consulted her at all, yet, I also have no memory of her disagreeing with this decision in any obvious way, 3 and we moved as a family in June 1972. Bob Thompson branded our Toyota station wagon with splashes of Yoruba-style protective medicines, and we drove West to the tunes of “Dark Side of the Moon” and Country Joe and the Fish.

I’ll return to this point of decision later.

Phase Seven: Wellesley Professor Descends to role of Tucson “Faculty Wife”

The University of Arizona had something like a “Nepotism Rule” (excluding spouses of faculty from holding positions, though the Department of anthropology did boast one husband-wife pair of professors.) and Helen aroused no interest in the Anthropology Department. (Feminism appeared to have little hold in 1972 Tucson — “Women’s Libbers” were described dismissively, for example, and “Faculty Wives” were of no more relevance here than at Yale.)

Here, she first got our sons Kevin and Michael established in local schools, while I soon became known as “the Hippie Professor”. (I began offering new courses, often on subjects for which I had little prepared. My reluctance to deal with complex social situations marginalized me in the Department, but I interacted with some graduate students well.)

So Helen began extending social networks where she could find people whose interests related to her own. She located fellow-mothers who shared her desires to open the eyes of their children — for example, she and a friend designed and taught a course on Religions of the World for their class at Unitarian-Universalist Church.4.

And Kevin and Michael became very activie at this time. They were three years old when we arrived in Tucson, and Helen was a strongly devoted mother for the next decade — some people thought she was too devoted, “overprotective”, she expected a lot from them — but I thought she was the best. I’ll let my lads comment more about her mothering in this Symposium, should they care to.

Around the university, she built links with female professors (Myra Dinnerstein in the History Department, later Women’s Studies, always acted as an especially valuable and influential friend. ). She briefly landed a job teaching at Pima Community College — but those doors were closed. She commuted for a while to teach at ASU. (That too was not a viable prospect ) She was not wasting her time: she met new worlds riding that slow-bus to Tempe, enlarging her grasp of “American Culture”: she brought back new social ideas to all of us. (Including new views of “the West”. For example, Helen encountered some “Sons of the Pioneers” on this bus, and one time chanced to sit beside Shadow Ray, my old Casper (Wyoming) Basketball Coach, who now Snow-birded between Wyoming and Coolidge, and talked with her about old times in the Casper of 1949. She listened to radio programs from rural Arizona, and brought us all social reports.)

Then, In 1975, Helen faced a major crisis, caused by her husband’s wandering losses of impulse control. (My son Kevin recently said to me, “You went AWOL from the family for a while back then”.) The fact is, she only faced it by 1975, when I decided to tell her about my situation (too-much psychedelics, a serious case of polyamory).

This brief statement covers a bit of what was in fact a decisive year for us: we had to decide about the future of our marriage, and full commitment was the issue we did resolve. Loyalty accrued for good things past must also have been a strong factor in our remaining together, and abandoning psychedelics carried me out from what had become a deep hole in my personal life

I provide these details (\(This is viewed by some of my commenters as giving too much detail, “embarrassing”, “Sullying Helen”, “enemies will use it against you”.) because I think that moment was decisive for our relationship: from that point on, everything did change (Slowly, and through my own consistent — and now actively supportive — behavior)). I started giving her wants priority, and (I’m guessing this, because we never opened up very much with each other ) she planned and began forging the next steps of her career.

During this time, Helen and I together took Yoga classes with a woman of astonishing qualities named Camilla Bersu, who provided these services at Temple Emanu-el in Tucson. A Holocaust survivor then in her nineties, she taught us to learn deep-centering, using materials and skills entirely her own (These included, memorably, the playing of scratchy vinyl records on a tiny ancient sound machine, the meanings of which nonetheless came through very well.). I think these courses were crucial for both of us, as her wisdom steadily built itself into us both.

In the summer of 1976, the Kreider-Henderson family embarked on a “round-the-Four-corners-states” trip with our boys plus the two Shimony sons from Wellesley, six of us in our Toyota Corona station wagon, on what

became a transformative adventure for us all. We camped out in tents along the way, and immersed ourselves in the truly Awesome Creation that is the Colorado Plateau. This was another step that changed our lives. (Ever since, that region has been Holy Ground for me (and Helen and I returned to it thereafter many times). See the 29 July 2017 issue of New Scientist for a useful discussion of how “Feeling Awe Makes People Happier and Less Stressed”, that is, how the experience of awesome environmental immersions — like good Psydelelics — can both expand and calm fevered brains. We never related better than after we experienced this enormous, mostly silent, endlessly-embracing place.)

Phase Eight: Helen expands her Feminist Research

Recall the political ferment brewing on the eastern seaboard when Helen’s dissertation appeared in 1969: by 1977, this had become a dynamic feminist power group in Washington, which now pushed in new laws at the national level. One was USAID’s creation of its Women in Development (WID) office in 1974, and this led to programs funding field research into women’s roles in West African farming. These programs aimed at land-grant colleges with strong agricultural faculties, so this kind of “women’s studies” reached the UA campus in 1977 when the University of Arizona Arid Lands Studies Program was awarded a relevant grant.

Helen had local helpers, so in 1977 she learned quickly about the Arid Lands Niger Natural Resources Program. While most of the men who commanded the project neither spoke French nor knew much about West Africa5, Helen, an expert in West African Anthropology, had both the French language and the area skills, but when she presented them, the Project Authorities showed little interest.

“Who do you know that you can use?”

We met a man at a Tucson party, where he took keen interest in Helen. She learned that he worked for the project, so she went to his office and consulted him. He said, “Who do you know that you can use?” Helen replied, “I couldn’t do something like that, ‘use’ somebody.” He repeated the question. Helen considered the few Washington DC connections we might have, and could only recall one: “Well, we know Allan Hoben, he works with AID.” Her new advisor replied, “That is the man who has the job of evaluating this project!”

We were old friends of the Hobens, part of our old Berkeley cohort.6).

I telephoned Allan and reported our problem, learned he would soon fly from DC to California, and he could stop awhile Tucson. We set a date, invited Arid Lands Niger Project officials to join us for a party, and they attended in large numbers. Allan circulated freely through the crowd, never mentioned Helen, and a week or so later Helen was invited to join the project.

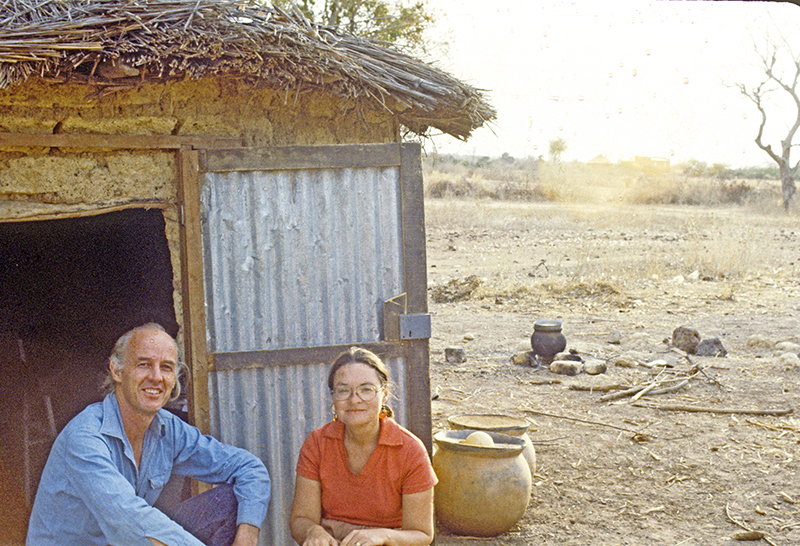

Helen now “got going”, off to Niger in West Africa, while Dick remained at home in charge of her boys (now eight years old), who worried about her a lot )(And also suffered some very low-standard cooking –my first effort was a chicken soup which I managed to burn badly on the bottom. My sons were quite courteous: “It’s all right, Dad — we’re not really hungry right now”. So I enrolled in a Chinese cooking class, learned that art from a real expert, and we three male “widowers” soon found ourselves eating fairly well.).

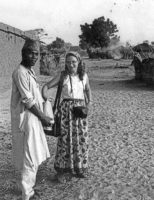

At left, Helen poses with the wives of the Falenko Chief, 1977. ( Helen writes, “These women are cloistered: their husband buys wood and brings water, so they remain in the compound during daylight hours. Because they are cloistered, they do not have to work in the fields. They are dressed alike, since Muslim law requires that all wives be treated equally.” [Thanks to Nancy Ferguson for unearthing this photo.])

From Helen we got air-mail letters, from a strikingly different person: less joking, more contemplative about working alone in the field, no longer fretting her “inadequacies”. The tales she told show that she had found “new ways”.7

“Gorko Madame” (Madame’s Man)

In Fall 1978, Arid Lands again sent her to West Africa, this time to Upper Volta (Now Burkina Faso.) to work in a remote village for a project emphasizing food production by women. I followed her in December solely for support, where I found her highly respected by everyone, from top AID people in Ouagadougou (The Director of the project, who met her at a party, observed her in action, leaned close to her and said breathlessly, “Vous et Unoubliable“), to small children of Koukoundi, who tended to gather round. I could see I was dealing with a new Force of Nature. (While there I became known as “Gorko Madame” — “Madame’s Man”; Helen gained great renown in these villages for her medical expertise, –after providing “Where There is No Doctor” help to a man gored by a cow, part of her daily task became providing “no-doctor” first aid to streams of ailing people who arrived at her door. )

From this time onward, Helen was team leader and I her assistant whenever she wanted , though her main activities now became networking with women across the country and then across the globe, always pursuing feminist goals. (While I became a “bit player” after 1977, I’m proud to say we acted as a team for about 45 years, so the growth of our particular versions of “feminism” was in part a joint effort. The team faced dissolution only once, and that too was a “feminist learning experience” for each of us.)

There will be more materials on Helen’s research work further below (though I will not discuss her work in BARA — that is a task better suited to others), specifically detailing her Dissertation contribution a bit, and then her later work toward publication. But first I want to look back at our history as I’ve outlined it above, looking at how far we came on our respective feminisms.

Reflections on Our Limited “Feminisms” Together

By late August of this year (Helen died in April, and her Symposium was scheduled for September, so I began the writing of this essay), I thought I had good grasp of the “feminist problem” in our relationship — by which I mean the basically “feminist” task of each communicating our felt needs to other, and listening to these differing perspectives — “sitting in circles”, as Gloria Steinem puts it. We never quite managed to do this — you might say, this was our failure to gain “Second-wave Feminism” with each other.

But memory is, as anthropologists and psychologists tell us, a very deceptive thing. Once I had reconstructed (in the “Phases” above) where we didn’t do these tasks, I kept thinking back to each of those major decision-points of these phases.

First, to Phase Four, the cat in the tent. I said that I was “adamant” that the cat should go. It was a unilateral decision. And it had not occurred to me to see that as problematic.

Second, what about the monumental Phase Six decision to leave Yale and come to Tucson? As I said, I don’t remember the details around that particular time, but searching my mind through the broader time period, two occasions came back to me — I’m going to say 1968, but on both of them I was suffering with my own hidden turmoils, on each occasion drinking — I “blew up” so to speak. One time I was working on “My Great Book”, and something Helen said angered me, so in response I shoved our record player so hard I damaged it. I remember feeling good doing that. A New York Times opinion piece for August 27, 2017 notes that It feels good to victimize others (bullying), while it hurts the victimized. That’s how bullying perpetuates itself. This outburst was a stark (if extremely brief) example.

So a light went on in my head: I INTIMIDATED Helen on some occasions when strong conflict emerged. I became VIOLENT — “not directly at her”: My mother had fixed this idea in me very strongly: don’t physically burt people, but above all don’t physically hurt a FEMALE. (But you can “throw something” in another direction to let them know how you feel, says the angry one.)

Now I turn to the third big decision moment, in Tucson, the time of my confession in 1975, when Helen thought I was trying to hurt her by presenting my news. Sometime well before that — 1973, 4, — our two boys were now sapient on the scene, and again, I was suffering in hidden turmoil — Helen and I had some kind of argument in the kitchen, the boys were present, and I threw a ceramic cup, against a wall — it shattered. For me, the memory ended there, but when we talked about this some years back, my son Michael said, “I thought you were throwing it at ME!”

So here’s the thought regarding gender, feminism: intimidating communications — however brief and physically indirect — are likely to damage gender, and feminist, interests in the future.

My father did that “acting out”, a very few times I was small, but those occasions terrified me and later I felt contempt for him. For Helen I know that Homer, her father, did some of that, “acting out”. ( As Nita said, “Don’t ever let a man know that you can type” — that meant, coercion of female is likely to follow.) Feelings of being coerced can operate on remote — stored in the memory of the participants.

In 1987, I took training in Conflict Mediation for the local Tucson program run by the City, then I participated in mediating local conflicts for a number of years, including cases involving domestic violence that had been referred to us by the courts. I think it’s accurate to say that we found, overall, that domestic violence cases were usually not amenable to mediation, because the problem of intimidation was rooted so deeply in these cases.

Jon Haukur Ingimundarson, our first Icelander student here, tells me (having read this essay) that this “Dick-the-Intimidator” image doesn’t fit, but he only arrived in Tucson in 1983. I’m just guessing that Helen’s memories of my “acting out” may have inhibited later behaviors. At this far-gone date –2017 — perhaps we’ll have to wait for other voices who have not yet spoken at this symposium.

(Here, allow me to add another thought regarding the landmark decision I made regarding our job choices in 1972, in light of its impact on the people at this Symposium: if we had stayed in the east, Helen in 1972 at Wellesley would have become merely a part of a large crowd swarming into feminist movements at the time. As it happened, substantially later, in Arizona from 1977 to 2001, she became immensely valuable in building strong feminisms right here in UA Anthropology. There was a big time-gap in the politics of these two locations, and her role here was hugely important during the 1977-2001 period. I personally am very happy we came here, but as regards Helen’s opinion on this, we may never know.)

Helen’s Book-writing Projects

Aside from her ongoing work at BARA (which I do not discuss in detail — that is work for others if they can find time to do it), Helen continued considering a return to Onitsha, now intending to explore the contemporary lives of Ndi-Onicha women. We worked together on various topics related to this during the years from the 1980s into the early 2000s, and she found it hard going in light of all her other obligations. Recently (2018), going through her various documents, we found an undated “diary” entry8 — I can only guess at the date. It may have been written before our 1992 trip (outlined here below), or it may have been done after, but I’m fairly sure it was sometime well before the publication of her co-edited, much more generally focused volume on gender, published in 19959

Here is the diary entry:

Book Writing

Getting a Ph.D was something I fell into since I did not originally (in Nigeria) think that I was capable of going that far academically. But I was encouraged by a professor completed course work in a year and went to New Haven with Dick on his first job. The first year there I studied for qualifying exams took them in the Spring in Berkeley and returned to New Haven. But Then I lapsed into a housewifely phase and put off working on the dissertation (except for reading and collecting some data) for several years. Finally due to fear of failing, and pressure from Berkeley I got started on it.

One cause of procrastination was that I had not really conducted ” field work” with a major theoretical premise, methodology etc. but had collected material for Dick ( as in the court cases) and in response to a request for Dick and me to write short manuscript on Ibo child training. So I interviewed women. I had to work with women (or so I thought) because men either wanted to exclude me to the kitchen (away from serious talk) or chase me around!

Anyway I thought I did not have anything original to say. This is still a problem. But I did pick some issues that I had researched e.g. Onitsha Ibo women’s religious ritual and religious objects and women’s representation as seen in funerals women of different status and contrasting these representations with those of men of similar statuses. I was looking for tie ins between women’s conducting rituals and being representated more or less as equals in a major ceremony funeral and their status in the economic and political sphere.

I am still looking at these themes, but I am opening up the dissertation chapters and re arranging the materials showing changes from ” remembered time” and observations of contemporary (l960’s) women.

And I am adding in more ” voices” points of view more or less as said by the women and men themselves.

Since a major theme in my dissertation (and also in Dick’s book) dealt with women as members of a patrilineage by birth (daughters/sisters) and women as as wives of a patrilineage into which they had married, I am dividing up a large dissertaiton section into several chapters. And I am looking for inconsistencies, problems in relationships that I think are now being idealized largely on the basis of Dick’s work. That is the relationship of sister and brother is examined by using material from native court cases of the early to middle 20th century and point of conflict identified. The same approach is used for the husband wife relationship.

A problem is sitting alone and doing the work. I think it is overwhelming that there is too much material and on the other that I have nothing significant to say. Yet I know that what I didn’t say (by not turning the Dissert. into a book) is being said by others . So clearly what I want to examine is valid and I would think so if somebody else was doing it.

So I invent excitements to escape working ALONE on the manuscript.

But I know I am not totally alone in this in that I can discuss issues with Dick and others in the Anthro Dept and show chapters for critique.

But only I can get the material down in a first draft.

On the one hand I wonder if writing the book is worth doing and if it will be criticized when its done but on the other I know that I am frightened and feel inadequate and that I don’t want to to be licked by this. And I need the book for tenure.

Phase Nine (For Richard): I Claim My Own Belated Feminism

Writing now in 2019, I realize that in preparing this essay in 2018 I completely forgot some important points of my own history (I was told at the time to include as little as feasible about my own personal matters), which now seem very important to clarify here. One crucial experience for me was being drawn into the social experience of learning to conduct activities of conflict mediation/resolution, which began in 1987 if I recall correctly. This was a project funded for a time by the City of Tucson, and was led by a very remarkable woman, Anne Yellott. During the training period and then later when I was involved in mediating local disputes of a considerable variety, I came to know many women active in the project, and I found them far more insightful and skillful in this field than most men. Patricia MacCorquodale of the Sociology Department at the University of Arizona was another very insightful teacher for me at that time. I became a fairly competent facilitator and mediator, an entirely new skill for me, and I am sure this entire experience (which included mediating domestic violence disputes, where women were generally the prime victims) opened my understanding of the politics of gender in an urgent new way. (I designed and taught a course in the UA Anthropology Department during the early 1990s, which wasn’t very successfuIl, but it was a serious effort. (I retired in 1996 in a state of complete psychological burnout.)

In the early 2000s, I began following the rise of Gabrielle Giffords in Arizona State politics, gave her strong support during her very difficult re-election as senator in 2010, and have remained a loyal supporter of her causes since her devastating injuries in 2012. I became a strong supporter of Hilary Clinton during her run for President in 2016, and for now-U.S. Senator Kirsten Sinema that same year. Viewing the current political scene, my favored candidates for President are Elizabeth Warren and Kamala Harris in that order, and I I view New York State Representative Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez as one of the brightest signs of hope for the future of our nation.

Overall, I do believe I finally became fully a feminist, through those experiences between 1987 and the early 1990s. (“Better Late than Never”, an old saw claims.) If we remain open in later life, we continue to transform ourselves, and the conflict resolution experiences did have a strong effect.

What happened when I wrote the main parts of this essay was that, as I uncovered more of my own un-spoken sexist underpinnings (and associated behaviors) from the time of our marriage in 1959 onward, I began to de-value myself, concluding with identifying the features I reflected upon earlier. I ended the essay feeling considerable chagrin, but felt I had to say it all. Now I see myself with what I consider to be a better sense of fairness.

Appendices:

1) Our Research Trip to Onitsha in 1992

[Note: for a full exposition of this visit, see Chapter eight, “Some Aftermaths”, the page entitled “1992: Brief Encounters…..”]

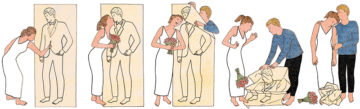

When our Onitsha relative Nneka Umunna told us she wanted to go back to Nigeria and to Onitsha in order to perform the Ikwa-Ozu (“Second Burial”, “Lamentation”) of her mother’s mother Nne-Ci, we decided that now was our time to return: with Nneka’s help we could organize meetings for Helen with important people who could further her efforts, and hopefully could observe and record the funeral.

The story of this journey belongs elsewhere10. Let it suffice here to observe: the research process began very well, but ended abruptly in our second night in Onitsha when Helen, accompanying a group of women walking uphill from our house along a deeply pot-holed road in pitch darkness, fell into a large drainage ditch and broke her ankle. 11 After desperate searching through the darkened city12, her rescue party found her a haven at St. Charles Borromeo Hospital (where they had a generator and therefore electric light). The patterns of our entire stay in Onitsha were drastically transformed, and Helen’s plans for book research completely disrupted (though we continued making efforts relating to it into the early 2000s).13

Kristin Loftsdottir, now a Professor of Anthropology at the University of Iceland, arrived in Tucson the late summer of 1992, as a beginning graduate student in UA Anthropology. Helen had just undergone the necessary surgeries to repair her broken ankle, and was bedridden at the time. Kristin sent me these comments regarding what appears above:

I will never forget that moment. You invited Arni and me to come by your house. I was very stressed and everything seemed so new and a little confusing because I did not know what was expected of me. You showed us in and there Helen was sitting in her chair and when we walk in she would smile this very special smile of hers that was both so kind and so full of life and almost a little mischievous. I did not understand nearly all what she was saying and what was happening because she was talking and laughing, calling “Dick, Dick, get them this, show them that…” It was wonderful! So welcoming, so unexpected. I did not know then of course how welcome I would feel every time in your home, how kind you both would be to me.

I remember when I stayed at your house when I did the preliminary defense. It felt like home, and l loved the bedroom I stayed with Helen’s beautiful dolls from her childhood.

Perhaps you should mention Helen as inspiration to her graduate students, her kindness toward them and how ready she was also to listen and give input. It would almost always be a cheerful moment full of laughter!

We visited Kristin and her family in Hafnarfjiordur in 1997, where I took this photo of them at dinner with Helen:

2: A few words on Her “Feminist Tract” Dissertation — “Ritual Roles of Women in Onitsha Ibo Society” (1969)

This 526-page volume begins with a broad survey/assessment of the varieties of Anthropological approaches to religion, overviews general patterns in “traditional” West African religious systems, then dives into the religious beliefs and sociopolitical structures of Ndi-Onicha in their prehistorical ecological situation. As she proceeds, she draws continual comparisons and contrasts of the statuses and roles of males vs females. As she proceeds she observes that “Some major social structural variables in Onitsha lay a basis for the active role of women in Onitsha society” (in a system where women are, broadly, demeaned).

This structural background in hand, she delves into the variety of roles Onitsha women play in the rich field of ritual processes, first a chapter on the broad domain of ritual in Onitsha and then a very close study of that immense social and cultural domain of death and funerary ritual in all its profound detail. She considers the range of beliefs regarding female (and male) identities, the shrines and other objects controlled by women (and men)14, how rights and duties, beliefs and obligations are distributed, enacted and disputed

during the elaborate stages of Death, Burial, Lamentation, and Reincarnation. In every ritual context, the powers and limitations of various women-identities — as Wives, Mothers, Daughters, traders, and others, and the social groups that form collectivities around these selves are measured and compared — the ranges and limitations of women’s power, how distinctive strengths may imply weaknesses in other social contexts. Then finally, she conducts a substantial comparative survey of other Igbo groups15. The entire work is a tour-de-force, given the data available at the time.

For the full content of this dissertation, see the earlier pages of Chapter Nine in this volume.

- Bureau of Applied Research in Anthropology, part of the University of Arizona’s School of Anthropology. [↩]

- More details about this phase just described will be found in the “About” page; scroll down to “More About the authors,” then scroll all the way to the bottom, to the section marke:d “Looking further backward in time: … sources of my deep affection for persons of Jewish descent….”

Phase Five: Onitsha, Nigeria: Uncertain Spouses in “Strong-Male” Cultures

So walking-wounded husband and now ambitious wife went to Nigeria in late summer 1960. We had no preparative time to research Igbo culture, but stopping en route in Helen’s hometown Harrisburg, Helen’s grandmother, who everyone regarded (with good reason) as a warm-heart-saint, smiled in meeting Dick and gave him her sage advice: “Be sure to stay away from the Blacks!”

Dick entered Onitsha anxious, but we were well received – most Onitsha people welcomed Americans in 1960 – and they liked Helen — she was socially adept, while my task was to change from friendly-smiling blank who shut down when confronted, into someone more active, aggressive, self-assertive. Fortunately, many Igbo-speakers behaved like psychotherapists, pushing me in directions of greater personal strength.

Among The Ndi=-gbo, we now met new social, cultural, and personal forces. The late Stanley Diamond, a gifted anthropologist who knew and admired the Igbo earlier, observed in a paper – he was drawing a contrast between the modern world ruled largely by what he called “dissociated men”, who turn real living action into abstractions, with people -– as he put it, “Reality BLAZES for them”. We now dealt with many people obviously alive with, and expressive of, their emotions. And over the course of nearly two years, it changed us. But it changed me much more, I think. Helen didn’t have to go so far (and, on the other hand, gender roles were newly different).

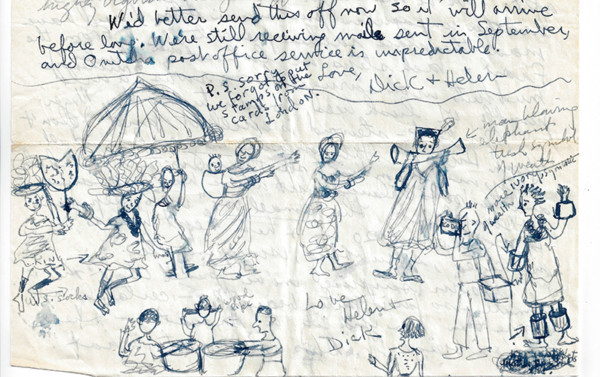

Helen settled quickly into our situation, and by a month after our arrival she recorded some first impressions (from the Obi Onicha‘s Ofala Festival) in a cartoon scribbled out on a letter sent to my two maternal aunts:

Helen’s October 1960 cartoon. Helen stands by our signatures at the bottom; Dick mans his “Kodak” (sic: I used an Aires camera). The whole city was indeed “split down the middle”: there was the “Inland Town”, a coherent, tradition-celebrating community organized by ancient “village-groups” in the Igbo manner, but also diversely structured and stratified, with titled chiefs and ruling “King” (the Obi).

They called themselves “Onitsha Ibos”. We moved into this group, eager to learn more about them. (I was searching what I imagined as everything pertinent to a “study of the City” — a goal which was, as any normal thinker would have warned, was “biting off far more than I could chew”. From the men (including some men boasting more degrees of formal education than I) I got long, often very philosophical discourses on just about everything); from most of the women, Helen received much less, almost entirely interpreted by girls of lesser education than the young men I worked with. In one of our audio-taped discussions, she complained about this women’s lack of a tendency to elaborate reflectively on details of their remembered lives. (Employment-age men were in a minority among our prime research population because most of them were working in Civil Service jobs elsewhere in Nigeria.)

Nearly surrounding this “Inland Town” was a much larger city, called the “Waterside”, most of these people called themselves “Non-Onitsha Ibos”, hyper-democratic, hyper-Christian, rejected Kingship and traditions, mostly traders, aggressively doing their things. (Cross-cutting this major ethnic divide was a large “Western-educated elite” — nearly all lived in the Waterside but they were strongly divided along the ethnic lines just described. Our tack was to contact elites when we needed them, but we did not engage them everyday. Both economically and culturally, it made sense for us to focus mainly on the Inland Town.)

What tasks for Helen?

We were told at Berkeley: “Don’t study women; WOMEN HAVE NO CULTURE.” We carried these blinders with us, and for various reasons never completely lost them. We were guided to study the tradition of Onitsha child-training (Robert and Barbara LeVine, field workers on the Six Cultures Study of Child Socialization at Harvard under John Whiting, gave us direction in this. ), which we did; and we could see that women held powers in some contexts, but for various reasons Helen found it very difficult to draw women out. (Since she lacked language facility, she found it hard to engage women. It did seem that most women she consulted had much less to say. This was an illusion, but a real gulf in Western Education access for women made it seem so, and Helen did not succeed in breaking these barriers. )

But she also took her typewriter into the Onitsha Customary Courthouse, where she spent many

months reading and recording Court cases dating back to 1910, where she found Onitsha women bringing charges against men, some of them testifying “I was the MAN who did this….” Some distinct points of gender interest arose — women could be more complex.

Helen continued her court cases, and she also became the primary typist of our many field notes (though I did a lot of this also). Helen’s mother Nita would have been appalled — she had pointedly warned Helen: “Don’t let any man know that you can type!” But I think Helen actually felt more comfortable and enjoyed this; it took her into worlds of male activity otherwise closed to her. )

Big Deaths:

Almost at once, in February 1961, two deaths: one mainly local — the Onitsha King died — and one hugely international — Patrice Lumumba, the former head of newly-independent Belgian Congo, was murdered by servers of Belgian interests.

Death of the Obi set in motion an interregnum that absorbed our time, drawing us into deeper research about the past. (since the “TRADITIONAL” procedures of succession to Throne now became issues, politically charged; the “Onitsha Ibos” now saw me as deserving respect and interest, thinking I might have hidden connections with the still-influential British officials who continued to occupy decisive positions in the Government which would stand to resolve the issue of who the next king would be. ).

Meanwhile in the Waterside, due to the death of Lumumba many “Non-Onitsha Ibos” I encountered would accost me with anger. (After Lumumba’s death in the Congo, local protesters gathered on the streets of Onitsha, held militant marches, and European-appearing people became open targets of abuse ). I became tougher (and also angrier, myself).

Further complicating things, the “New Nation” of Nigeria was slowly tearing apart. (we watched, with some dismay. Together, the national and international scenes drew us together, despite our obvious interpersonal tensions.)

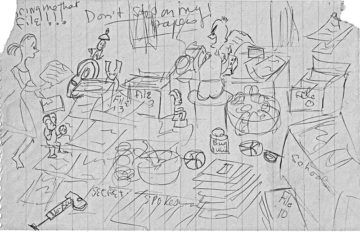

The upshot of all this was important in terms of feminism: I became increasingly confrontational with everyone, a quietly stronger, more visibly6 angry man. Helen’s 1962 cartoon here illustrates our situation. (This scene is a bit “intimidating“, one might say.)

.To summarize “Phase Five”: both Helen and I matured greatly, and despite all our problems we stayed bonded Our fieldwork experts had told us that husband-wife fieldwork is a supreme test for any marriage, and we passed that test.

When we left Nigeria, we enjoyed vacations in Rome, Cologne, and London on the way home, which greatly soothed our haggard lives All of this touring was financed by Helen’s mother, who as a person dedicated to the fine arts strongly urged us to tour Rome and Florence. Here I insert a point that is relevant in several situations of our lives together: transitions, sharp changes in ” ritual context”, were very important — entering “Awesome Experiences” can make powerful healings in people’s lives; our trip to grand cities, the hill country of Orvieto, Florence et al — a tremendously stimulating but also relaxing period as anger melted in situations so different from what had gone before. See the 29 July 2017 issue of New Scientist for a useful discussion of how “Feeling Awe Makes People Happier and Less Stressed”.)

Returning to Berkeley, Helen’s relationship with the more “Assertive Man” moderated as Dick finished his dissertation in the spring of 1963, while

Helen worked to prepare for her own Ph.D. exams . (Clifford Geertz was there, she took a course from him. Geertz participated in progressive national-political protests arising in Berkeley at that time, but we stayed single-minded, largely passive in our relation to these active oppositions to the “House Un-American Activities Committee”, the budding “Free Speech” movements on campus, the stirring of “Black Power” , etc. )

I then landed a job teaching at Yale and we drove across country to New Haven, Connecticut and searched for housing there.

Phase Six: The “Magical Mystery Tour”: Life in New Haven, 1963-72

Here, the back side of 360 Edwards Street, facing the rest of Yale Campus, running downhill to the south for many blocks — this provided an apartment for us for almost seven years (1964-70). Details in footnote. (this 19th-Century Mansion had been converted into a number of apartments, reserved mainly for visiting faculty. Our rooms were inside the white structure at top right, part of the 4th-level “Servants’ Quarters”, while six or seven other renters lived about, including in the former kitchen at far right base, which still had the remnants of a dumb-waiter that led upstairs to what was once the “dining room”. (the Fire-escape ladder was added after we had moved out.) For a considerable time Helen acted as “Super” for this building, a task she performed quite effectively and memorably including some marvelous cartoon-notices that gave gentle direction to new residents (some of whom were exceedingtly outlandish by Yale standards — much more outlandish than we were). Thrilling memories reside in this house; at one point, an undergraduate friend and I successfully brewed multi-bottles of sparkling hard cider in the basement, while a huge oil-burning furnace chugged fiercely nearby — observe the mighty chimney serving it at top right.)

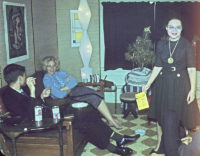

At left, Helen at a party for Anthro graduate students in 1965. While Helen was now designated apart as a “Faculty Wife”, we widened circles of interesting friends. Our lives intensified in many directions between 1963 and 66: I had to learn how to teach, and I did. We both worked Onitsha stuff into publication. Helen studied for her Berkeley Ph.D. Qualifying exams, went there to take and passed them, returned home to start her dissertation.

From 1967 on,

we engaged many activities far beyond “academic”: local, state, national, international politics — labor issues, black power, marching against the Vietnam War; the Civil War in Nigeria. Our Biafra-supportive efforts failed, but we met Anne-Marie Shimony, Head of Anthropology at Wellesley College, and in 1968 she offered Helen a job teaching at Wellesley (which of course Helen took.) This meant Helen commuted to Boston every week. (Hillary Clinton was there at the time; ’68 was her junior year, when she supported Eugene McCarthy for President. Helen voted for him; I thought that foolish, and was right (given the outcome). Hillary spoke at her own graduation in 1969, receiving a 2 minute ovation. I don’t think Helen attended that event, and I have no idea to what extent Wellesley campus politics touched Helen in any way, though it must have had some effect on her)

Helen and I differed profoundly in one crucial way: I think she avoided exploring the wilderness of her own consciousness. (I have lots of evidence for this from my own viewpoint, though others who knew her may remember differently. One example, but I think it revealing: when Helen’s Alzheimer’s became obvious to many after 2000, she steadfastly refused to face it: looking into that interior prospect was just off-limits. This is just one case example among many. ) I was a polar opposite: “opening the doors of perception” became my goal years before we met. (As a late-teen-ager in an Air Force barrack, I read Sigmund Freud and Aldous Huxley, et al, and Huxley’s views about “the doors of perception” became an obsession, opening new directions to follow. I yearned for Peyote in 1950s New Mexico, but had no clue where or how to find it.)

So when psychedelics flowered at Yale in the mid-1960s, I leapt right in, and revelations permanently changed me. Helen leaned toward impulse control — she adhered to our social science categories, while I leaned sharply toward greater degrees of imaginative and behavioral freedom — I joined Sergeant Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band. I’m not quite sure how it links to our prime issue of “feminism”, though somehow it does: as I see it, during this time, Helen adopted strong “social-science realism” studying “women’s access to power in traditional Onitsha”, while my categories and behavior regarding sexuality and gender, for example, widened. Kurt Anderson’s essay here (see the image) suggests that these psychedelic “New Age” ideas — “All you need is love”; Peace, not war, the Hippies celebrating at left, etc. — undermined America’s formerly shared views of “reality”, thus launched all sorts of weird “alternative realities”, spreading a cognitive and moral chaos that now — seven decades later — he sees as engulfing us all (the image at right).

Anderson claims that, before psychedelics, American cognitive disorders were largely confined within the “demonizing religions” of our past, but now anything or anyone can demonize (or be demonized), a social condition he sees as breeding chaos. My take is, this may be partly true, but 1960s “freeing of consciousness” also had much wider personal, social, and cultural effects than Anderson seems to allow. It helped propel a number of important movements — the massive political marches on Washington against a grotesque, evil war in Vietnam, and the power surge of “The Women’s Movement” that arose around the same time.

Freeing of consciousness may definitely have positive social and cultural value — if it retains links to impulse control. But there’s part of the rub. I take Oliver Sacks as my guide in these matters. Sachs’s works over the past 45 years provide just one example of how far cultural-psychological understandings have progressed since the 1960s. Even more cogent for today is the new book by Michael Pollan ((2018, How to Change Your Mind, Penguin Press [↩]

- Photographs of her at this time do suggest a pensive turn, but (again, to my memory) she did not complain. [↩]

- Claire Scheuren was an essential support for Helen’s self-worth at this time. For the children who experienced their particular course, some eyes must have been widely opened indeed. [↩]

- One senior figure always spoke knowingly of “The African farmer, he….”; another, possessing no facility with French whatever, created some very comical moments, for example when he boldly typed out a Program for a meeting with visiting Niger officials, sprinkling his few French words through the text in most bizarre fashion. [↩]

- I gave him decisive job support in 1972 when he needed it (and he deserved it — in my experience he was one of the most brilliant anthropologists in our discipline. [↩]

- We have somehow misplaced all these letters — I hope to find them sometime as we continue exploring her “archives”, recalling more about this time. I have a copy of her report on the project (again, thanks to Nancy Ferguson). [↩]

- She did not keep a diary, but very occasionally wrote down her thoughts. [↩]

- Henderson & Ellen Hansen, eds. [↩]

- see the Aftermaths Chapter in AmightyTree, where it is outlined but not yet developed. [↩]

- Dick was guiding the group along the road with our sole flashlight; Helen had left her glasses behind, and apparently “saw” the ditch as a smoother pathway. [↩]

- One person recommended the “Evolution Hospital” where there was said to be a “good bone doctor”. Driving there, we found a massive three-storey building, entirely dark except for what appeared to be a single candle burning far upstairs. Helen said to Nneka, “Please don’t put me in there!” [↩]

- See “Scatterings of Truth” in Chapter 8 “Asides” in Amightytree, where Dick recounts one of his own brief adventures during this time. [↩]

- The religious “identities” of women have permanence beyond death (as do those of men); mothers may be incorporated into shrines (like men). Men are required to bring in ghosts of their mothers (as well as those of their sisters/daughters). Powers of influence flow through ancestral women to their descendants. [↩]

- and even briefly considers the Yoruba. In all these cases she asks what factors appear to favor political strength in one domain, for example (Collective Wives), and weakness in another (lineage Daughters), and so on. [↩]