“When Our Father is Sought but Not Seen”

(na achoro nna-anyi, ma afu)

[Note: Click on any image you may want to enlarge.]

On July 26, 1961, Aniweta and I join with a group composed mainly of Umu-EzeAroli elders at J.J. Enwezor’s River Side Hotel (left) river- side Hotel, where we view the street from the second floor before departing to meet the men of the sub-village Mgbelekeke, keepers of the Mother-Earth-of-Onitsha (Ani-Onicha) shrine at the base of Old Market Road in Otu (the featured image above shows the venue from the hotel’s upper storey). Here Igwe Enwezor is to perform his ritual petition to that mighty Alusi. The Igwe himself may not attend, being now in his holiness, though he is there in the hotel. Helen as a woman is also required to remain there. But the Igwe‘s prime representative is present, in the form of his senior brother Akunne, whose task is to work with the priest of Mgbelekeke Family, presenting materials, receiving blessings, and generally ensuring that all goes well in the ritual ).

On July 26, 1961, Aniweta and I join with a group composed mainly of Umu-EzeAroli elders at J.J. Enwezor’s River Side Hotel (left) river- side Hotel, where we view the street from the second floor before departing to meet the men of the sub-village Mgbelekeke, keepers of the Mother-Earth-of-Onitsha (Ani-Onicha) shrine at the base of Old Market Road in Otu (the featured image above shows the venue from the hotel’s upper storey). Here Igwe Enwezor is to perform his ritual petition to that mighty Alusi. The Igwe himself may not attend, being now in his holiness, though he is there in the hotel. Helen as a woman is also required to remain there. But the Igwe‘s prime representative is present, in the form of his senior brother Akunne, whose task is to work with the priest of Mgbelekeke Family, presenting materials, receiving blessings, and generally ensuring that all goes well in the ritual ).

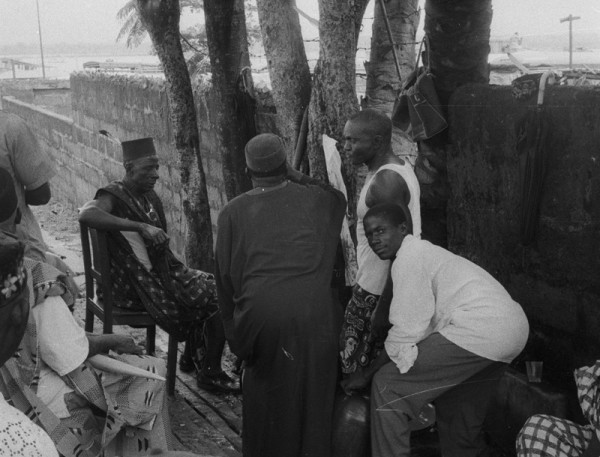

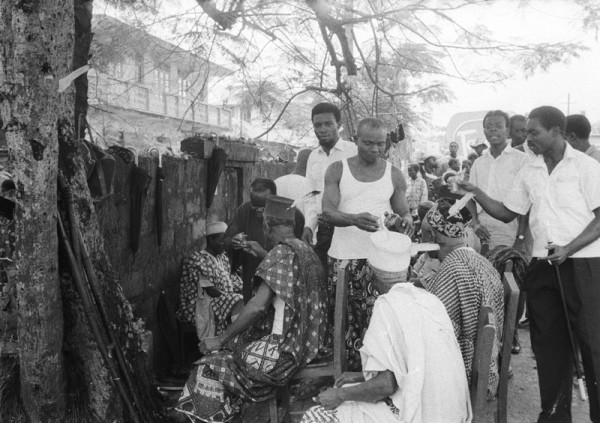

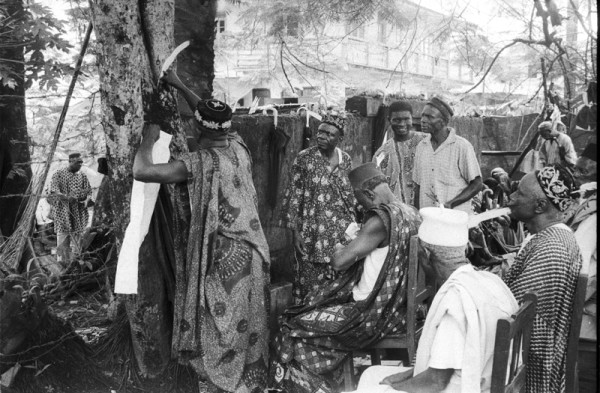

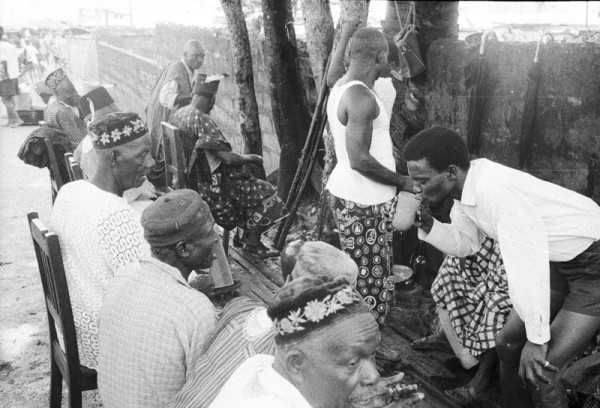

The masters of the ritual procedure have set up chairs along the boardwalk that covers the open drainage ditch flanking Road and Shrine (the latter mostly enclosed within a high wall). Barclays Bank stands across the street, along which massive lorries thunder past, scant feet from the congregants as the driverss ply them on uphill runs heading toward Enugu.

Below, members of the congregation sit in front of that portion of the Sacred Grove (Okwu-Ani)which will receive the offerings. The Diokpala of Mgbelekeke Family, Onwuta the Osuma (an Onye-ichie-ukpo, senior among the Ranking Chiefs or Ndichie Okwa) presides (his support for Enwezor’s candidacy may of course be presumed from his acceptance of the task to perform the ritual). Half a dozen Ozo-titled men sit in the chairs provided (though un-titled men ae also allowed to sit there at times).

The congregation is composed of a variety of Umu-EzeAroli elders and youths together with a few members of the Mgbelekeke family (who conduct the rituals as the traditional caretakers of the shrine, led by their senior priest and ranking chief).

The congregation is composed of a variety of Umu-EzeAroli elders and youths together with a few members of the Mgbelekeke family (who conduct the rituals as the traditional caretakers of the shrine, led by their senior priest and ranking chief).

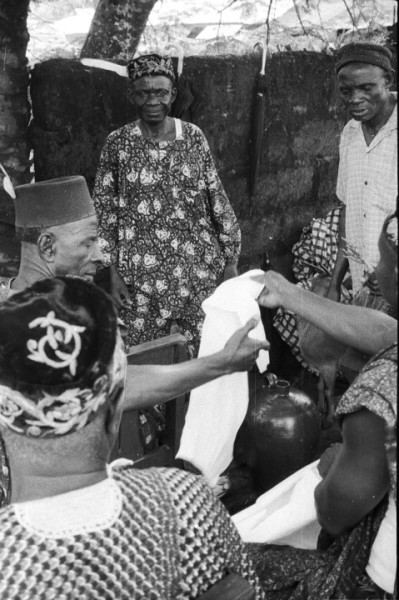

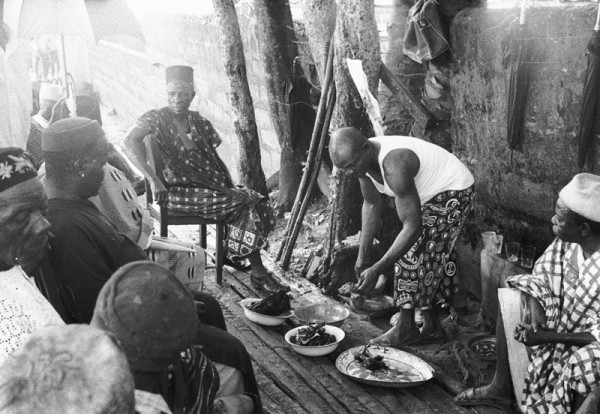

Below, Akunne Enwezor bends over several main ritual gifts: Kola nuts, white cloth, an eagle (Ugo) feather,Mmanya Oka (maize wine, a favorite of Ani),)palm wine, the rectangular bottle of Dutch Schnapps, the Head Fish (Azu-isi), a hen, a she-goat, and a pile of white clay/chalk (Nzu), an essential food for the Mother Earth. The Osuma observes the measures.

As the first steps of the ritual begin, with the Ani receiving her eagle feather (Ugo), Enwezor’s followers express their elation. Obiekwe Aniweta (standing just right of Akunne, below) emphasizes that yesterday’s meeting of the chiefs have demonstrated the efficacy of Enwezor’s recent expenditures on their behalf (affirming an amount of £200 given prior to yesterday’s meeting). He states that the culminating rituals of kingship are now only a few days away.

As the first steps of the ritual begin, with the Ani receiving her eagle feather (Ugo), Enwezor’s followers express their elation. Obiekwe Aniweta (standing just right of Akunne, below) emphasizes that yesterday’s meeting of the chiefs have demonstrated the efficacy of Enwezor’s recent expenditures on their behalf (affirming an amount of £200 given prior to yesterday’s meeting). He states that the culminating rituals of kingship are now only a few days away.

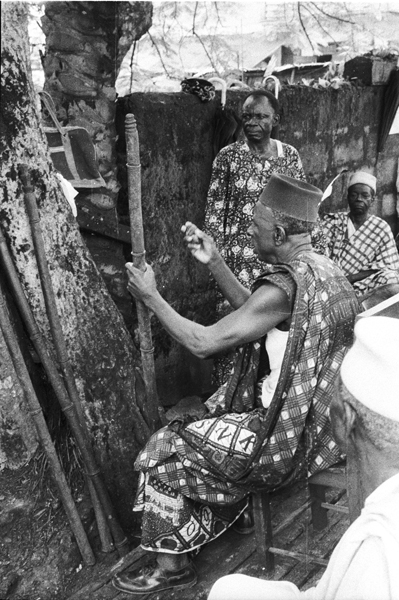

The Osuma begins the formal ritual by breaking kola on the tree, then praying to the Ani and to Onicha-Ebo-Itenani (“Onitsha-the-Nine-Clans”). He touches one piece of kola all around the tree, then gives it to Akunne Enwezor; he then chews his own piece of kola, and spits it over the tree, while the assembly calls out “Ani-Onicha, O..!”

The Osuma begins the formal ritual by breaking kola on the tree, then praying to the Ani and to Onicha-Ebo-Itenani (“Onitsha-the-Nine-Clans”). He touches one piece of kola all around the tree, then gives it to Akunne Enwezor; he then chews his own piece of kola, and spits it over the tree, while the assembly calls out “Ani-Onicha, O..!”

Egbuji Ezenwa of Ogbe-Ozala, an untitled man given that honorary name (“child of Eze”) and a man of respected knowledge, can be seen seated behind Akunne)

Then Osuma receives the white cloth with which to dress Her.

Then Osuma receives the white cloth with which to dress Her.

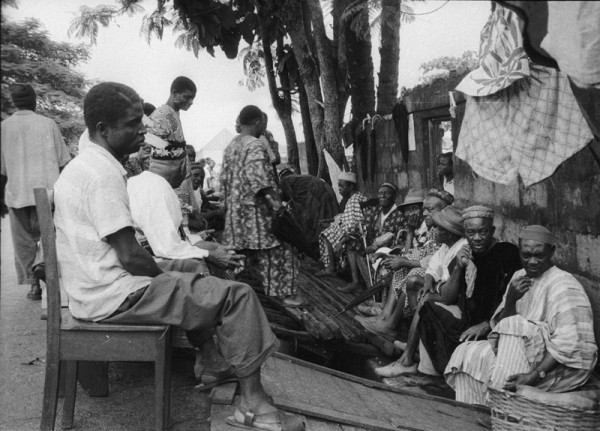

Congregants wait patiently while this is being done. At left front, Umera Anazonwu sits beside an Ozo-titled elder. The Maize Wine is poured on the tree. The Osuma calls Akunne Enwezor, handing a gourdful for him to drink, the rest is then distributed to other elders (who in turn call their dependents to partake).

Congregants wait patiently while this is being done. At left front, Umera Anazonwu sits beside an Ozo-titled elder. The Maize Wine is poured on the tree. The Osuma calls Akunne Enwezor, handing a gourdful for him to drink, the rest is then distributed to other elders (who in turn call their dependents to partake).

Looking toward the Shrine from the end of Nottidge Street, one might not notice anything going on except for the small cluster of people lounging about. But from time to time Ndi-Igbo traders congregate, and the Ndi-Onicha youths disperse them if they become at all intrusive.

Looking toward the Shrine from the end of Nottidge Street, one might not notice anything going on except for the small cluster of people lounging about. But from time to time Ndi-Igbo traders congregate, and the Ndi-Onicha youths disperse them if they become at all intrusive.

Now the Osuma takes the offered hen and rubs its body against the tree trunk embodying the Mother Earth.

Now the Osuma takes the offered hen and rubs its body against the tree trunk embodying the Mother Earth.

He then neatly strips the feathers from its throat, cuts its throat with his knife, then spreads the blood over ossissi, tree, and white cloth lyng at his feet. He then takes feathers and touches them onto the blood running down the tree and cloth and Ossissi.

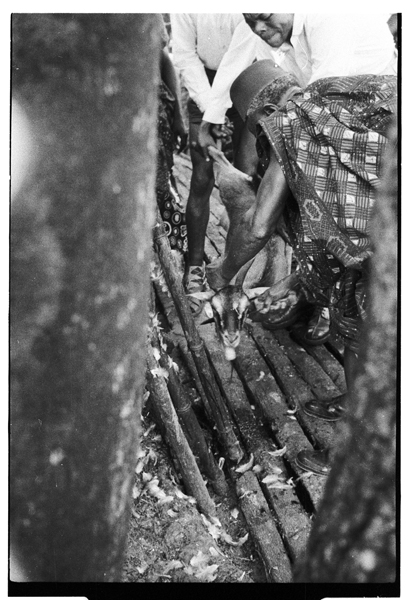

Then he makes an effort to cut the throat of the proffered goat, but the knife seems dull (a chronic condition I observed in distress when attending a number of goat sacrifices in Onitsha).

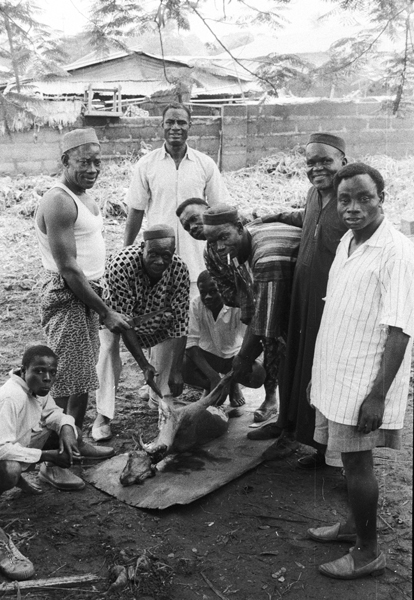

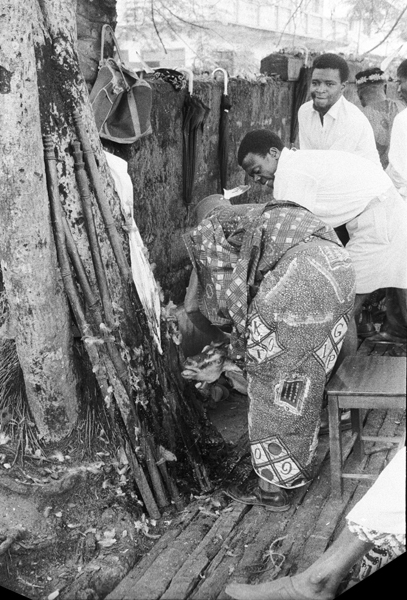

Then he makes an effort to cut the throat of the proffered goat, but the knife seems dull (a chronic condition I observed in distress when attending a number of goat sacrifices in Onitsha). He needs assistance to complete the task. (Note the assembled Ossissi, Ozo-Title Staves, placed where they will receive part of the blood of sacrifice.) The goat’s blood is distributed in the same way as that of the Hen.

He needs assistance to complete the task. (Note the assembled Ossissi, Ozo-Title Staves, placed where they will receive part of the blood of sacrifice.) The goat’s blood is distributed in the same way as that of the Hen.

Members of the Mgbelekeke work crew now prepare the goat for cooking, done inside the sanctuary (where a fire has been started as the ritual began). Philip Obanye (rear center)and Abomeli (at left) are in charge.

Members of the Mgbelekeke work crew now prepare the goat for cooking, done inside the sanctuary (where a fire has been started as the ritual began). Philip Obanye (rear center)and Abomeli (at left) are in charge.

Offering palm wine to Ani proceeds, as elders drink some offered to them and then call upon their juniors to come and drink also.

Offering palm wine to Ani proceeds, as elders drink some offered to them and then call upon their juniors to come and drink also.

Gin is then distributed in small shot glasses amply provided.

Gin is then distributed in small shot glasses amply provided.

While we wait for the goat to cook, a young man appears, dressed in something like a Brooks Brothers suit with tie, wearing sunglasses, and is introduced as “Okafor from Umu-Anyo, from Lagos”. He comments to me briefly something about “my people doing one of their native ceremonies”, and leaves shortly thereafter.

When the food is cooked and ready, portions are sorted out under the watchful eye of the priests. (The head of the goat and the Head Fish is served first, mixed with palm oil and salt, the jaw of the goat presented to Ani and pieces of meat and fish placed on the tree.)

The bulk of the open-fire-roasted goat is then cut into small pieces for distribution to the assembly. An argument arises over whether the meat has been adequately cooked, some elders commenting on its pinkness, but the Igwe‘s senior wife (an Nne–Mmanwu, “Mother of the Dead”, hence qualified to work in the Ani sanctuary and who had supervised the cooking) affirms that it is.

The bulk of the open-fire-roasted goat is then cut into small pieces for distribution to the assembly. An argument arises over whether the meat has been adequately cooked, some elders commenting on its pinkness, but the Igwe‘s senior wife (an Nne–Mmanwu, “Mother of the Dead”, hence qualified to work in the Ani sanctuary and who had supervised the cooking) affirms that it is.

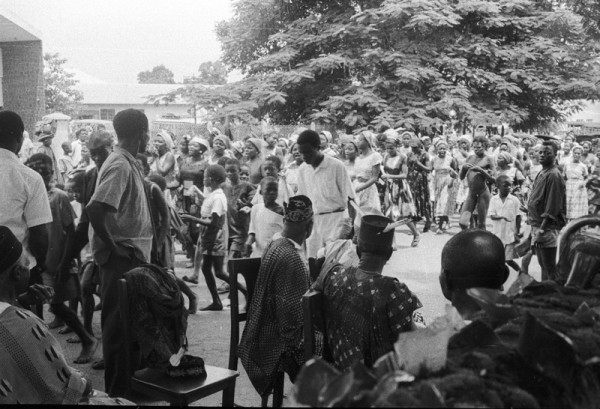

Now, during the long time we sit waiting, a very noteworthy event impinges on our ritual. This day is the 104th anniversary of the CMS’s arrival in Onitsha, an event celebrated in many ways but as we are sitting there a very long parade of school children (of various genders and ages), women’s groups and various others proceeds to march past. They are making a clockwise circuit, first dancing and singing down New Market Road past the Main Market, and then circling to turn up Old Market Road and past our shrine location.

Now, during the long time we sit waiting, a very noteworthy event impinges on our ritual. This day is the 104th anniversary of the CMS’s arrival in Onitsha, an event celebrated in many ways but as we are sitting there a very long parade of school children (of various genders and ages), women’s groups and various others proceeds to march past. They are making a clockwise circuit, first dancing and singing down New Market Road past the Main Market, and then circling to turn up Old Market Road and past our shrine location.

This is a very long and quite congested event, and the assembled groups find themselves standing in place for considerable periods of time. As they do, our assembled elders and youths see many local people they recognize, and at various times women of these groups break out of line to greet their men, and extended conversations follow. Below, a large women’s group passes by, singing and dancing as they go. I suddenly am startled to notice a nearly naked Onye-ala (Mad Person) accompanying them as he walks up the road. Nobody pays him much heed.

Below, a large women’s group passes by, singing and dancing as they go. I suddenly am startled to notice a nearly naked Onye-ala (Mad Person) accompanying them as he walks up the road. Nobody pays him much heed.

Below, you see one of the singers observing the strange person suddenly appearing at her side. She registers surprise, perhaps, but doesn’t lose her beat in the song-and-dance.

After the processions have passed and everyone has been properly fed, Akunne Enwezor as leader of his Umu-EzeAroli ritual team, celebrates the moment by blowing his Ivory Horn Trumpet (Okwu-Odu), accompanied by another Ozo man seated below him. It seems a suitable ending, a sound by which the Old Onitsha Market Place at this location was formerly known (Otu-OkwuOdu).

After the processions have passed and everyone has been properly fed, Akunne Enwezor as leader of his Umu-EzeAroli ritual team, celebrates the moment by blowing his Ivory Horn Trumpet (Okwu-Odu), accompanied by another Ozo man seated below him. It seems a suitable ending, a sound by which the Old Onitsha Market Place at this location was formerly known (Otu-OkwuOdu).

In the final act of the ritual, Akunne Enwezor and Mrs. Enwezor place money into a pan, where it is washed in water and then distributed among both titled and untitled men. I receive sixpense as my share (and of course have partaken in all of the other goods offered to Mother Earth as well).