Chapter Two — entitled “Deep-searching Histories” — contains a massive body of detail. Some parts — especially the early page entitled “:Deep Historic roots of the Igbo Language”, which provides the most accurate estimates of very old prehistoric social and cultural connections among speakers of various languages over various periods of time, also presents a kind of read-“killer” for most readers. It outlines almost the entire language history of Africa, only gradually entering recent times,. While I think it’s reasonably accurate, I conclude that most readers should skip that page –including all 6 of its sub-sections (unless you are committed to learning a lot of tangential detail about those very distant times) The last subsection, on “The Dispersion of Igbo”, is more relevant than the others.

So proceed — after reading this current page! — directly to to the subsequent page, entitled “Niger-Benue Worlds…..”. This page (and those that follow it) I regard as indispensable for a good understanding of ‘Deep Onitsha History.” But recognizing the importance of an initial “Overview” of the whole, I present this current page as that broad overview of what is to follow in much greater detail.

………………………..

I direct this Precis of Onitsha History primarily to those who , having some familiarity with Onitsha, are inclined to summarize its past with very simplistic constructions like “Onitsha People came from Ife”, or “Onitsha People came from Benin.” Both of these statements are false as summaries of what actually happened (though it is true that Onitsha People have historical connections to these places). What follows here at first aims to provide an initial corrective understanding for those kinds of grossly misplaced summary views, and to prepare you for further materials to follow.

1. “Folk History” summaries are inaccurate in very important ways:

First, a general point. we should all be aware that there are important differences between what I am calling “folk history” and “accuracy-tested”, scientifically-informed histories, which we might call “real history”, except that all histories are in a sense are in a sense visits to “foreign places” — we cannot actually “go there.”, and so our “real’ constructions are at best based on carefully-measured evidence. Without that control, human stories about the past tend to be so strongly skewed by the story-teller’s social-political opinions and, more broadly, by his or her basic understandings of what is “real”. that the tale told is best regarded as fantastic. We humans have marvelous capacities to create stories which intermix the real and the imaginary in ways that sometimes become powerfully suggestive, for example in Kurt Vonneguts novel Slaughterhouse Five. But a real history must exclude stories that contradict available evidence.

Questions about what is “real” are not of course concerned only with matters of distant past. We see this every day in our current public discourse, where prominent politicians present blatant lies as “true” versions of our very current realities. In these cases their political motivations for constructing the stories are quite obvious to anyone aiming to uphold standards of truth . But when we deal with the distant past, distortions of truth — while no less frequent — are often not so “obvious,” especially where they seem “realistic” in principle. to any viewer who approaches them with appropriate skepticism.

Let me then start with a widely-known case-example of the contrast:

The Biblical [= “Folk-historical”] text of “Sodom and Gomorrah” in light of new Scientifixc evidence:

The Judeo-Christian Bible is entirely composed of “folk stories”, stories told by people about many kinds of things and events, which eventually were written down by storey-tellers whose motives were mainly moralistic,, subjected to amendments and other editing over long periods of time, and regarded (by its devoted followers) as “true”.

For example, in the Book of Genesis (19) the Almighty (and angry) God sends two of his angels to destroy Sodom, whose citizens have profoundly offended him. After his angels lead the (morally well-behaved) citizen Lot and his family away, God does rain fire and sulfur on these cities, and “all of their inhabitants”, and “on everything that grows there”.

How can we assess the “truth value” of a story of this kind? A first step for anyone who values science would be to doubt the presence and agency of supernataural beings who possess human-like motivations but also possess obviously super-human powers. A second step would then be to look for evidence of very unusual happenings in the location in question.

We now have scientific evidence, drawn from very recent Archeological and geo-scientific work done in the Jordan River Valley, Radioactive dating indicates that, around 1650 BC.E. (“Before the Christian Era”) a cosmic air-burst destroyed Tall el-Hammam, a Middle-Bronze-Age city in the southern Jordan Valley northeast of the Dead Sea. The proposed airburst was larger than the 1908 explosion known to have occurred over Tunguska, in, Siberia, where a roughly 50-meter-wide meteor detonated overhead with ~ 1000 times more energy than the Hiroshima atomic bomb, and lay wasste to a vast circle of forest trees surrounding the radius of the blast. (The event was not direclty witnessed by any known human survivors, though the sound of the b last was heard in some long-distant locations around the world at that time.)

At the vicinity of “Tell-el Hamman”, a city-wide ~ 1.5-meter-thick carbon-and-ash-rich destruction layer has been found, which contains peak concentrations of shocked quartz, melted pottery and mudbricks, diamond-like carbon, soot, iron- and silicon-rich spherules; and melted platinum, iridium, nickel, gold, silver, zircon, chromite, and quartz. Heating experiments indicate temperatures exceeded 2000 °C at ground level. Amid city-side devastation, the airburst demolished 12+ meters of the 4-to-5-story palace complex and the massive 4-m-thick mudbrick rampart, while causing extreme disarticulation and skeletal fragmentation in human remains (bones are found in jumbled arrays at the site) . An airburst-related influx of salt from the nearby Dead Sea fell onto the land, produced hyper-salinity of the soil, causing a ~ 300–600-year-long abandonment of about 120 regional settlements within a greater than 25-km radius. 1

So we learn that a catastrophic event did occur at this location, but the sciences involved also tell us that the collision of a meteor with earth’s atmosphere is entirely a product of the spatial positions and momenta of the two objects colliding, that such collisions occur without the intervention of human (or super-human) wills or hands. These collisions have occurred throughout the history of the earth — indeed, such collisons over time created the earth –, though with continuously decreasing frequency (the last one comparable to the one that hit Tell-el Hamman [that we are aware of] occurred in the remote area of Tunguska, Siberia in 1908, as we outlined above.

And we may entirely dismiss the Biblical morality tales attached to this larger story — for esample, of Lot’s wife being turned into a pillar of salt as an angel’s righteous punishment for her supposed failure to follow a trivial command, though large amounts of salt did fall on the earth there at that time and later passersby may have observed a pillar or two or at least substantial piles of it. (This minor portion of the story suggests, by the way, the gratuitous insertion of a male chauvinist fantasy by the storyteller(s). From that perspective, It perhaps added credibility to blame a hapless woman as a minor part of the tale.)

I think the contrast between a history based on scientific knowledge and on based on “folk tales” is clear here. Both “stories” tell of a disaster that “really occurred”, but the one that traces the event to the intersection of a meteor randomly colliding with the planet earth has strong “truth value” while the one attributed to the acts of a God angry at the “wickedness” of the population in question has no truth value whatever, beyond recording that a disastrous event did occur at this location at some remote time in the past (and perhaps that people of local communities of that time tended to find deep faults in the morality of socially-competing neighboring towns).

And of course we may also infer that all writers of Folk History at the time of the horrific event tended to blame serious natural disasters on one or another supernatural agency (responding to perceived human faults),, thus drawing moral lessons to fit the tellers’ goals and attitudes at the time. . All stories should be examined for teller’s bias, and much of that is evident here.

It would not be wise to infer that today’s socially-involved humanity is all that different. An event of the magnitude of Tel-El-Hamman, happening over one of today’s major cities in our current global political climate, just might set off World War Three. Humans are quick to attach blame for important disastrous events, but careful observation and reasoning make all the difference in the quality of stories being told.

Pursuing the lessons: Some examples of Onitsha “Folk History”

Perhaps two brief examples here of such “summary views” of “Onitsha People’s past” are in order. Here I attach a portion of the first page of M.O. Ibeziako’s chapbook (published in 1938), The Founder and Some Celebrities of Onitsha“:

Mr. Ibeziako was a very prominent Onitsha Indigene (about whom I write elsewhere2 This version of “history” carries Onitsha connections all the way back to Egypt, actively invoking the biblical stories of Moses. Such sweeping accounts — claiming to be “histories” — were frequent at the time Mr. Ibeziako wrote his book, in fact one British official who worked for a time at Nri in northern Igboland was a firm devotee of the “Egyptian Origins” hypothesis then current in some European circles of historical opinion in the 1930s, which held that most l large-scale (“civilized”) historical developments around the world came from Egypt. 3.

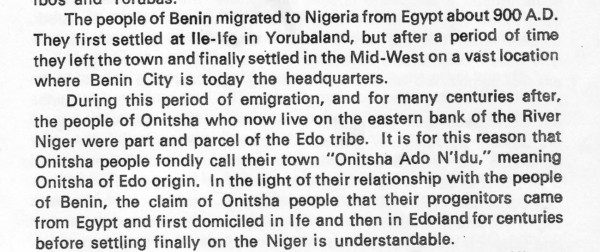

Since Ibeziako’s book, a number of writers have continued to give credence to such ideas. here is a passage from S.I. Bosah’s Groundwork of the History and Culture of Onitsha

Allow me to say here: I am a great admirer of Mr. Bosah’s book overall, which is an outstanding account of many aspects of Onitsha culture. However, this particular passage is another very strong example of “folk history” tht has been pfroduced by educated Onitsha people, meaning stories about the past formerly spread by tales told verbally, previously passed from elders to youths (the kinds of stories which have grown up in all cultures over time,) but which — from what we now know from carefully recorded, cross-culturaly compared l histories — using historical linguistics, archeology and many other scientific methods to test reality values — cannot be regarded as historically true.

2. Genuine histories use carefully critical methods and testing

For example: none of the three major language groups being discussed here — Yoruba, Benin, Igbo — have any traceable linguistic connections with Egypt: the Language Families from which these three known lagnguages come are entirely separate from those found in and around Egypt. We know from archaeology that all three of these three Nigeria-area languages were roughly in their present locations by 900 AD. The people of Benin did not first settle in Ife (in Yorubaland) and then “leave the town” to go and settle in Benin. The people of “Onitsha Ado-n’idu” were never “part and parcel of the Edo Tribe”, though they have been profoundly influenced, even perhaps may have been socially controlled, perhaps at some time had agents from Benin overseeing their existence to some degree in the distant past. Onitsha people’s language had core roots in Ika- Igbo-speakers, and the similarity of some of their words with those of Benin are due in part to “borrowing of words” (an ancient practice in all languages) and in part to the fact that their languages are cognate (related languages continue to share some very similar words for a long time after their ancestral tongues have separated).

So Of course the speakers of these three sets of languages do have cultural -historical connections. Social and cultural scientists, historians, etc have been tracing these connections carefully for more than a century. If you want to see the full details of the actual linguistic-historical connections of the Igbo group of tongues to other languages of Africa, please do plunge into the very next section of this chapter — ” Prehistoric roots of the Igbo Language” — which will show you in detail a sequence of historic roots that link them with other languages located in a pre-historically west-northwestward direction (the geographical opposite of a “connection to languages of Egypt”). And, as you will see in the third page of this chapter — on “Niger-Benue Worlds” — that Onitsha people do indeed have (very deep, ancient, if indirect) connections with Egypt, but these are histoaric-technological connections that arose through long-distance trade linkages, not “people coming from Egypt to settle” (insofar as any real evidence tells us) . 4

3 Our Brief Precis of Onitsha History

The Onitsha Kingdom you see today is the product of far more than a thousand years of dynamic, creative history. As the Anthropologist Igor Kopytoff once observed, “ most African polities and societies have been constructed out of the bits and pieces (human and cultural) of [previously] existing societies. “

Our Kingdom — “Onicha mmillli“ was its original name to distinguish it from near-by and closely-related Igbo-speaking people — “Onitsha of the River Niger” — began its historically recent identity as a modest community formed of “village groups”, located on the east bank of that great river, where its flow absorbs the Anambra stream coming down from very extensive swamplands directly north — some time around 1600 A.D.5

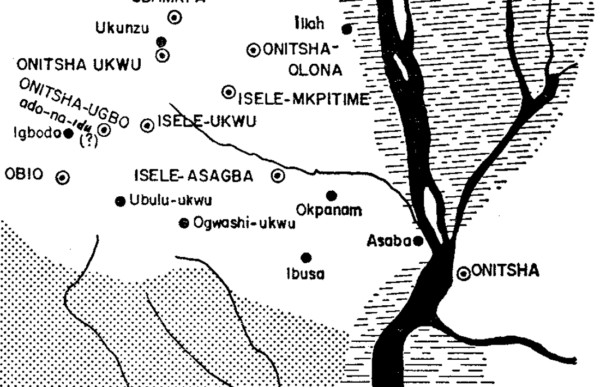

The people who called themselves “Onicha” there at that time claimed that they came from across the river in the western part of Igbo-speaker-land, where other communities sharing that name continue to exist there today, identifying themselves as such — “Onitsha Ukwu”, “Onicha Olona”, “Onicha Ugfbo” and other circled on the map who share some features of self-identification with this group. This points to an immediate companionate origin of closely-related people. How Onitsha people made this river-crossing is uncertain (but one particular folk story — that they rode over by standing on the backs of Manatees, — can safely be regarded as pure fantasy). 6

But the deeper roots of these Onitsha communities — more than a thousand years earlier — lie further north, where the two greatest rivers o West Africa — the Niger and the Benue — meet , have their confluence coming out of two opposite sides of that large portion of the African continent.

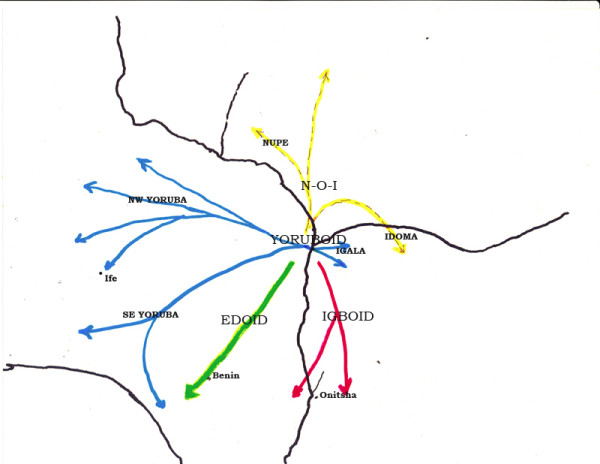

In this region of the Niger-Benue-confluence lived the ancestors of most of the major language groups now occupying our (southern) part of today’s nation of Nigeria: language groups now labelled the Yoruba, the Edo (people related to the Kingdom of Benin), the Igbo, and some others that we need not discuss here .7

Scientists in the field of Historical Linguistics call this ancient “Proto-Language” a branch of an even older group called “West Benue-Congo”, bu we may disregard the name. The point is that in that far-ancient time, these ancestors spoke a single language that later broke apart into these several later groups. as speakers divided into separate communities.

They were at first a “stone-age” people at that (rivers-centered) location, where they used their riverine skills to trade both in east-west directions and also traded to the north, across the Sahel-Sahara dry zones to exchange goods with populations linked to the Mediterranean region.

During these early connections (before later separations occurred),, this Confluence community participated in the development of metallurgy, — a major new technological age of copper, bronze, and iron production, which massively transformed all of their lives: new ways of producing food, cutting down forests to build things, and engaging more potently in warfare (both within groups and without) — changes which , as populations expanded, broke this unitary group apart into several different groups moving in different directions..

Each of these sub-groups began spreading out — like radiating new sprouts abandoning a former mother- plant , into the several directions where their respective language- descendants now dwell: in the north and western portions, the Yoruba— (and Igala—) speakers; east of them, the Edo- spekers (notably, the future empire of Benin), and east of these, the speakers of Igbo. Each of these groups began to differentiate into speakers of a separate language, which in turn grew distinctive dialects as each group expanded their range.

(The details of the spread of Igbo dialects will be presented in the third section of this chapter, labelled “Niger-Benue Worlds……. …Iagbo dispersionn”.)

All of f these groups — we will speak mainly of three, but there were several more — shared some characteristics due to their new metallurgical technologies: increased social complexities, some social stratifications, complicating divisions of labor, etc. With their new economic and political capacities, societies became more complex, as “chiefdoms” and small “kingdoms” emerged. These new social formations also began communicating with each other. We may think of them as early “civilizations”, interacting.

I now provide a brief discussion of three main groups engaging in this disperion:

(1) The Civilization in and around Nri (in Igboland) (in place around 900 AD)

Note that here I give the briefest introduction of the Nri complex, to which I will devote several subsequent sections of this chapter describing this historically very important cultural system. Here the aim is merely to briefly contrast it with the two other systems (of Yoruba and Benin).

At left, the bronze double-bell gong complex with embracing “cock” and radiating “fertile moons”. This mind-boggling piece of Hi-tech artistry was found in the Igbo-Isaiah portion of the complex.8

Some of the beads found in this part of the Igbo-Ukwu complex of artifacts came from the medieval Fustel workshops in Cairo, Egypt (by means of long-distance trade routes whose location(s) remain debatable among contemporary historians).

All of the precise (time-measured) historical evidence associated with archaeology tells us — this is very surprising to some and perhaps even now not accepted by some ”authorities” in the historical sciences — that the earliest — and technologically one of the most astonishingly sophisticated — of these civilizations is the one that arose in the location around what we label “Nri”, in the north eastern part of Igboland. The accomplishments of this great kingdom have been presented in great detail in two grand volumes labelled “Igbo-Ukwu” by the author Thurston Shaw, demonstrating achievements in the metallurgical arts that were in some aspects superior to what was being done in (for example) Europe at the time (ca 900 AD). You will see much more detail on this civilization below, in this chapter, in the page labelled “Easterly core: the Igbo-Ukwu Wonderland.”

Observe at left (from the Igbo-Ukwu complex), atop the handle of a bronze staff of office, the figure of a royal ruler astride a horse. This King displays on his forehead and cheeks the ichi scars that designate a holder of the Ozo title throughout the easternn part of Igboland. This icon shows that the ichi scars on the face of royalty (and other agents of the Ozo complex) trace back to the earliest phases of the Kingdom

Witness (at left) this array of marvelous wooden statues , a display devoted to illustrating the ichi scarifications attendant to Ozo title-takingt in Igboland EAST of the River Niger. As we can see above, these patterns reflect an ancient practice (at least a thousand years old). 9

This very distinctive feature of the Nri complex was part of the a ritualizing form of social organization we call the “Nze-Ozo complex”, a form of spiritual purification and uplifting socio-ritual activities that in a sense “democratized” the Kingdom, giving potential access to any man to a form of social uplifting that made him in some sense the equal of any exalted person of the wider social group.10

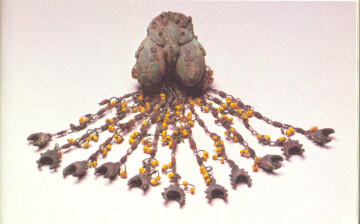

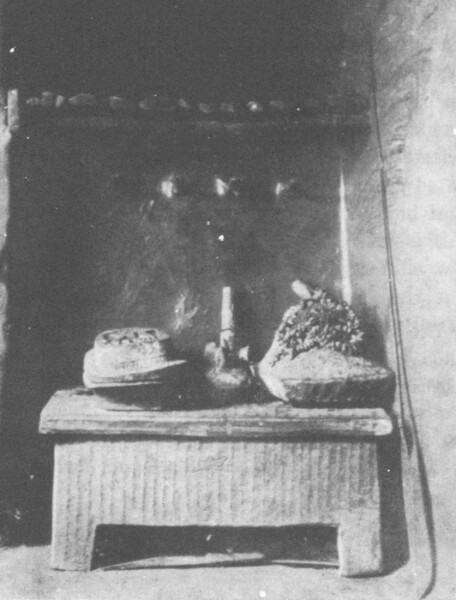

With the spread of this ritual complex across the Niger, the ichi scarring associated with this title system faded out for title-taking initiates there (this is a very dangerous form of scarification), but the Nze complex took strong root in Western Igboland. The pioneer ethnographer of western Igboland, Northcote Thomas, photographed at right what he called the “Nze” shrine objecdt at Onitsha-Olona. The object at left is definitely an Ozo-title-related objedct.

Settting aside, then, this brief diversion into an aspect of the distinctive quality of the cultural grounding of Western Igbo-speakers within this deep historical complex of the Igbo-Ukwu-revealed Nri Kingdom, we must observe that, unfortunately, some details of this civilization remain murky, because the Nri Kingdom was apparently built at its outset in uplands that were undergoing severe soil erosion and depletion, leading to what appears to have become a partial collapse of social quality over some centuries.

As the quality of their soil eroded, the kingdom was forced to “export” their culture, which they sought to do by sending out various Nri (and Nri-related) agents — ironworkers, providers of rituals, medicines and various organizational methodologies — that spread their influence into other parts of Igboland, mainly westward across the Niger into those parts of Igboland where ancestral Onitsha groups were locating. The towns of Igboland west of the Niger indicated on the map above were all influenced to some degree by the se Nri-connected “missionaries”, many of whom settled in and their descendants became part of these towns.

Among these boons brought from Nri was the Nze-Ozo complex just outlined, and this socio-cultural feature became part of these Onitsha groups, and groups of other names in what we’re here calling “Western Igboland”. ( (Note that problems of group designation arise here; by “Igboland” I am designating locations of speakers of the Igbo language, not people who may (or may not) designate themselves as “Igbo People”.)) At some early time, the people of Benin also received some considerable influence from this early “missionary” expansion of the Nri complex (though not, apparently, the Nze-Ozo complex).

(2) The Yoruba-speaking kingdoms related to Ife. (1200-1400 AD)

We will not discuss these Yoruba kingdoms further here, butt the bronze image you see at left is much more familiar to the western public than are those I displayed just above.

I’ll merely say this about the Yoruba: though the origins of this complex civilization are somewhat later than those of the Nri civilization, they were located on more stable, fertile soils and their prosperities and cultural elaborations (walled cities, for example) eventually far outpaced that of Nri. Their influence on Western Igboland occurred largely through their strongly “paternalistic” historic connections with Benin., which greatly stimulated the latter. This we’ll discuss directly below, but one aspect of the Benin expansion did include the formation of some small Yoruba-speaking enclaves in Western Igboland.

(3) The Kingdom of Benin (Edo) (1180-1897)

At Left, a marvelous example of Benin metallurgical art, displaying nicely the dominant motifs of Bini artworks: warriors ready for combat.11

This great socio-political formation, which grew out of a relationship to Ife, evolved strongly militaristic tendencies which became an elaborate slave-seizing and slave-trading political economy after they encountered Portuguese slave-seeking ships on the Guinea Coast weound 1450 AD. Gunpowder became a decisive means, along with elaborate developments in mobilization of manpower and elaboration of military tactics, of subduing societies within their reach, which at one point at least stretched all the way to the West banks of the Niger River.

Their dominance spread well into the ranks of the Western Igbo-speakers, including the “Onitsha” groups we have discussed here, and these recipient societies adopted their own copies of (some aspects of) Benin warfare organization, prominently including named ranks of titled “military chiefs”. The disruptive attacks from Benin set some of these adapting societies in motion, including groups who eventually crossed the Niger to getaway from Benin’s reach. This included the kingdom we have previously labeled “Onitsha mmili”, and also the people of Aboh, who made their own escape into the swamplands of the Niger Delta (where they proceeded to establish their own version of a militaristic and slave-trading Kingdom).

As a result of these — sometimes invasive — influences of Benin, the groups who founded Onitsha definitely possessed a number of sociocultural features: human-sacrificial kingship, titled “warrior chiefs”, and the elaborate ritual procedures associated with these complex socio-cultural features , which made them substantially different from their neighbors. (These real differences provided a basis for the much later political conflicts arising between these two groups during — and beyond — the Colonial Era. ) 12

……………………………

Hopefully this brief summary provides context for grasping the flow of Onitsha’s “Deep History”. In later pages of this chapter, succeeding phases outline the pre- (and proto-) European building of relationships along the Niger prior to the transformational changes when British Colonial forces, agents of the Anglican and then Roman Catholic mission, etc., landed in Onitsha (and changed this kingdom from a small and struggling social formation into an agency which eventually gained considerable historical importance of its own).

- Source: Bunch, Ted E., et al, 2021, Scientific Reports 11;1:18632. [↩]

- See the page devoted to him in Chapter eight. [↩]

- see for example Jeffreys 1934 [↩]

- Fantasies are another matter. A recent novel does trace Onitsha ancestors directly to Egypt. See LeClezio 1997 But fantasies are not history: “Star Wars” may be a fun movie, but don’t confuse it with real history. [↩]

- See Henderson 1972 for a detailed account of this “founding”, and also of course the page on “Niger-Benue Worlds” in this chapter, below . [↩]

- Map source: Henderson 1972: Fig. 3, p. 46 [↩]

- The details of this deeper language history will be found in the page which follows this one, labelled “Prte-Historic Roots of the Igbo language”. Here we focus only on the more recent branches of a series of larger related language groups. [↩]

- Seefor example Plates 274-7 in Volume II of Shaw 1970.. [↩]

- Image source: Front page, Casanovas 2010. [↩]

- The title of my 1972 book, “The King in Every Man”, made obeisance to this distinctive cultural formation. [↩]

- Wikipedia image from “Benin Bronzes” page. [↩]

- See for example, in Chapter Three, the page “Power and Paradox in Onitsha”, where interaction between King (Obi) and Chiefs (Ndi-Ichie) display activities quite different from those of their early Ndid-Igbo neighbors. For considerably more detail, see the page in this chapter entitled “Slave Trade and its Stereotypes”. [↩]