Michael Ogoejiofor Ibeziako is a major figure in Onitsha history. 1 Born in 1904 in Onitsha, he was a great-grandson of the historically prominent Onye-Onicha chief Ogene Eze-Oba of Ogboli-Olosi.

This ancestral figure (whose name “Eze-Oba” is a combination of Onitsha and Benin royal titles, devised by him) became a serious threat to the very definition of Onitsha kingship in the late 19th century, when he blatantly usurped several of Obi Anazonwu’s royal prerogatives. 2 He was only brought down by a subterfuge organized by Obi Anazonwu with the help of Royal Niger Company police. Akunne Oranye, an Onye-Onicha elder I interviewed in 1960-61 (when he was 75), witnessed this event at Otu in 1898.

According to Oranye, Eze-Oba finally breached the limits of tolerable behavior when he had one of his own sons sacrificed to make a protective medicine for himself. Anazonwu contacted Onwuli (a man of Iyawu Village serving as a Royal Niger Company policeman, who later became Onowu of Onitsha) who in his capacity as an RNC agent lived in the Waterside just west of what is now Christ Church. Onwuli directed the KIng to ring the royal bell announcing a meeting at that location, to be held among all Onitsha Senior Chiefs. When Eze-Oba arrived at the meeting, he was arrested, and (since there was no prison at Onitsha) taken by RNC agents across the Niger to Asaba (where he died a few days later). This ended what was effectively a major rebellion against the Obi Onicha.

Ibeziako’s mother was a native of Umu-Anyo family of Umu-Aroli (thus making him a Daughter’s Child to Igwe Enwezor’s sub-village within Umu-EzeAroli). Educated first at St. Mary’s (RCM) School Onitsha, he then attended the prestigious Hope Waddell Institute in Calabar, from which he joined the Civil Service, first working as a court clerk in what was then the Southeastern State of Nigeria. (His early associates remembered him as a remarkably driven man, with both indomitable will to succeed and considerable organizational ability.) There he became fluent in the Ibibio language, and became an interpreter for his colonial superiors, thereby gaining a cross-cultural perspective that would eventually serve him well. (He maintained his fluency in Ibibio throughout his life.)

Eventually transferred to the Resident’s Office in Onitsha, Ibeziako soon found a new opportunity: assisting Dr. C.K. Meek in his studies of Igbo law. Meek was Anthropological Officer for the Nigerian Administrative Service, where he had previously gained a considerable reputation from his publications regarding various Northern Nigerian “Tribes”. Then In 1929 Meek was given the major assignment to “determine how the principles of ‘Indirect Rule’ should be applied to Iboland”3. His research (undertaken in response to widespread women’s “riots” that occurred in Southeastern Nigeria during 1929, which proved highly alarming to Colonial authorities), aimed to identify traditional authority structures among the Igbo-speaking peoples which might serve as more legitimate indigenous bases for Indirect Rule than had the previous “Warrant Chief” system.4 In the Introduction to his subsequent widely-praised (and authoritatively followed) book5 Meek offered his “most cordial thanks” to various British officials and other authorities, and to “numerous members of the Ibo tribe, particuarly Mr. F. Ejiogu of Owerri, and Mr. M.O. Ibeziako of Onitsha, who gave ready, patient, and courteous assistance”.

This was highly unusual Colonial praise for a young “native man” at that time, and his prestige on the local scene rose for many other reasons as well. Overlapping with his research for Meek, he managed as an Onye-Onicha “native” to perform services for Onitsha Township authorities who would otherwise have confronted implacable opposition from those “natives”. For example, when introduction of pipe-born water to Otu was proposed, the influential Ikporo-Onicha (representing the entire female Ndi-Onicha membership) mobilized to oppose the project (on the grounds that it seemed to threaten t their ritual controls over Nkisi Stream, but Ibeziako was able to disarm them by careful persuasion (appealing to concerns for their own children’s health).

Meanwhile he managed to participate in the path-breaking extra-curricular activity of organizing the first local branch of the modernizing assocation named the Onitsha Improvement Union (OIU), building on ground prepared through publication of the first “Onitsha Ibo Almanac” in 1933. Significantly, this almanac (which bears a very strong stamp of Ibeziako’s hand) proclaimed as its guiding “Motto” Ibeziako’s own personal code: “Not Failure But Low Aim is Crime”.

During the first three formative years of the OIU , Ibeziako’s energetic activities (along with those of a number of his cohort there) produced major changes in the organization of Onitsha Township. In response to proposals made by these impressively creative men, the colonial government established a new Onitsha Native Administration (ONA), which in 1938 for the first time included non-traditional, educated “members of the intelligentsia” (as the Onitsha Province Annual Report for 1939 put it)6. Prominent among these was Ibeziako (who was made the first secretary of the ONA Council).7.

During this same period (as if he might otherwise suffer from ennui), he was competing in more abstract intellectual terms with other well-educated and highly regarded local Ndi-Onicha elders, who were known to be engaged in writing what each hoped would be the first authoritative history of Ndi-Onicha, and he (in his own fashion) upstaged them all in 1938 by publishing his own book, The founder and Celebrities of Onitsha. This locally-printed volume was surely one of the earliest productions of what would eventually become the internationally-admired phenomenon of “Onitsha market Literature.”8

His interests in Ndi-Onicha traditional culture also led him to finance and assist a group of Ndi-Onicha girls (members of one particular Age-grade) who sought him to become their Patron. He helped finance their dress uniforms, arranged to hire rental jewelry for their performances, assisted in their rigorous (and secretive) training, prepared feasts for them for their performances, and then joined them in their events. The anthropologist Sylvia Leith-Ross recounted a performance of his “ballet group”, describing the “dress finery worn by the girls”, as well as Ibeziako, “resplendently draped in the same velvet as the girls, a round velvet cap upon his head, a square fan in his hand.” She noted that some girls carred “small square boxes trimmed brightly with velvet and small round mirrors, and destined to receive the offerings of the audience.” (Leith-Ross 1942:4-42, 45.)

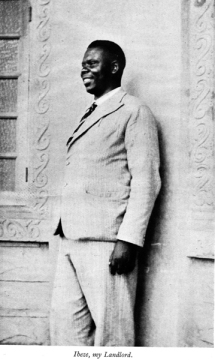

When Leith-Ross first arrived in Onitsha to make “a study of the town” in 1937, Ibeziako (as a former interpreter for Meek and as Secretary of the new, dynamic local branch of the Onitsha Improvement Union), immediately became a helpful and informative contact, in contrast to (as she reported), “…the Resident. Friendlily non-commital. ‘If you don’t bother me, I won’t bother you’ attitude…. All officials are… a little disapproving of white women going to live in native towns” (Leith-Ross 1942:14). Seeking a place to stay in the Waterside, she observed “It’s a new feature to me, this house building as a form of personal expression — at least I suppose it is that, since practically none of the houses are occupied.” (14-15) When she met Ibeziako and saw his unoccupied Otu house, she remarked “It is really a very good house, the best native-built and owned one I have so far seen…. I can rent the top floor only… From a built-out upstairs terrace, I can survey almost the whole downward length of Old market Road, and its upward length to its junction with New Market Road. At the junction is a pump That nearly decides me… To the right, perceived between distant palm trees, there is a grey band…. The Niger. That does decide me.”(15-6)

So she rented the upper floor of his just completed and impressive Waterside building at 60 Old Market Road, where she lived much of her brief (5+ months) stay in Onitsha. Having some problems deciding about methods of work, she resolved these in part (as she put it) by opting for tactics like “sitting still”, “to sit back with half-closed eyes, merged as far as possible in the physical and psychological landscape, unnoticed, and therefore undisturbing, and to record my impressions as they came to me.” (8)

to this anthropologist, this idea of research seems prpossterous, but “to each, his own”. While she did travel considerably around the town, dealt with a variety of people, and eventually wrote an interesting if very impressionistic (one might say fragmentary) report, Ndi-Onicha who remembered her to me recalled that she did seem to spend a lot of time sitting on her upstairs terrace in Ibeziako’s house.

Ibeziako was a source of many conversations she later discussed (as were a number of local market women and other professional men). When she later published a book about her Onitsha experiences, she wrote about many of her interactions with him (identified just as “Ibeze”), for example:9

“His face has a look which is cheerful, confiding, ingratiatingly sure that everybody must take to him; yet he has an occasional frown as of a puzzled child. Life, change, white man, black man, God, Government, it’s all too much for him; all at once, and in such big doses. Frank, loquacious, self centred, yet with unexpected reticences and delicate consideration; awake, interested, observant, yet with staggering ignorances balanced by equally staggering capacities for seeing things as they are. He’s voracious like all the Ibo I have known, though in a pleasanter, more childish way, and sometimes voracious for the intangible as well as the tangible.” (18)

Observing that he showed an intense desire for “civilization”, possessing ideas “of citizenship in a brave new world, some kind of freedom and splendor”, she went on to add,

“But how dissect chaos…? Talking with Ibeze is like walking through a landscape seen in a dream, a gravelled path bordered by good English railings will suddenly narrow and twist snakewise through a jungle; the railings sway, and grow and thicken, and become palm trunks; the neat, firm lawn begins to quiver, black mud oozes up, one’s feet stumble over tussocks and squelch through oily water; the modest violet turns into a fantastic orchid; the trim ivy into flamboyant creepers; the song of birds into shrill flutings; and the familiar thud of the woodman’s axe becomes the beat of savage drums. You start a conversation on Evangelical Christianity, and it leads you on to witchcraft; or on the commercial uses of oil nuts, and you plunge into reincarnation….” (19)

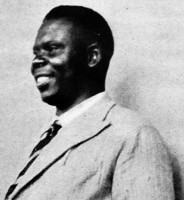

See a closeup of her fine photograph of him at right, labeled simply “Ibeze, my landlord”.

Her words seem insufferably florid today , but in her own way she did register what many observers have experienced in comparable situations: a tendency to alternate rapidly between “western-objective” analytical frameworks and those evoking radically “other” points of view. She would have been wiser to render such observations in simple descriptive terms, since (despite her comments elsewhere expressing great fondness for hm), “the beat of savage drums” no longer resonates as a useful observation (and I have doubts about how it may have sounded to Ndi-Onicha of the 1940s).

Ibeziako could not have read Leith-Ross’s book before 1942 (when it was published),though it’s safe to say he would have found such passages infuriating . (I did hear from some Onitsha people that he often expressed outrage regarding this particular book.) However, in a sense Ndi-Onicha eventually afforded him some degree of symbolic revenge, since when I asked one of my finest consultants, Akunne Akpom in 1961 about what memories he might have of her, he recalled that “everyone knew” she had become Ibeziako’s lover, and spent most of her days sitting on her balcony waiting for him to come and receive her eager embrace. (Based on my own sense of her character — derived from her writings –, this bit of Local Wisdom is preposterous, but of course “We can never know”.)

However, Ibeziako’s life underwent some really staggering changes only a few years after her departure. According to one account, while he was still Secretary both to the OIU and to the ONA Council, and also a clerk in the Resident’s office, he openly “transgressed the Nmo” (mmanwu, the Incarnate Dead Masquerade organization)10, from which traditionally capital offense he was personally rescued by Resident D.P.J. O’Connor, saved from the real, imminent prospect of being killed (“disposed of”) by members of his own village Ogboli-Olosi.11 Soon thereafter, he was transferred out of Onitsha, to the Nigerian Secretariat in Lagos.

After serving there from 1940‑42, when he tried but failed to find funds permitting his travel to the United States to pursue further education, he retired from the Service and embarked instead (in 1942) on a journey to the United Kingdom to pursue a law degree (during which voyage, the ship carrying him was torpedoed and sunk, though he was among those rescued). In London he studied Law at the Middle Temple, and was called to the Bar there two years later.

Upon his return to Nigeria, he set up private legal practice in Lagos as a Barrister and Solicitor of the Supreme Court of Nigeria in June 1945. Thereafter, all the while in private practice, he also played an active role in Onitsha politics and development.

After an extended period while living there, by which time he had long lost any naive trust of Europeans or commitment to following European ways, he proceeded to embrace the nationalist cause, and began writing a variety of essays in Zik’s West African Pilot, for example about Labor problems in the Enugu Colleries.. one example we see reflected in Onitsha’s Nigerian Spokesman , reporting on september 22, 1947, an essay by Ibeziako regarding a visit by Lord Hailey to Nigeria, where he observes that “Whitemen cannot understand our aspirations;” that an overhaul of the Native Authority macchinery is needed:. the powers and duties of Native Authorities should be enlarged. At the present time, he says, a District Officer acting as Magistrate , “though he knows nothing of English law …. can quash judgments based on native customary laws too complex for hi to understand.”

The man’s native brilliance had found new venues to explore.

After contributing substantially to the cause of Nigerian Independence through his career in Lagos, including his writings in the Pilot, he returned to Onitsha and was awarded the chieftaincy title of Onopli by Obi Okkosi II.

By 1960 he had a reputation for rigid insistence on having his way and for vindictiveness toward those who opposed him, and when I met him he behaved in what I experienced as an alarmingly overbearing and challenging manner, telling me in our first meeting that I must come to him and write down exactly what he told me, to make certain I “get everything right.”12

Having been informed he was training his own son in England to become an anthropological historian, and because of his litigious reputation, I avoided further contact with him, partly out of fear that my later dissertation and/or journal publications might become bogged down with legal disputes. By doing so, of course, I cut myself off from what was obviously a valuable source of information, but dealing competently with him was probably far beyond my capabilities at the time. In his final Report on the Obidship competition of 1961-62, Commissioner R.W. Harding simply remarked of him: 13

“The Onoli –President of the Ndichie-Okwaraeze. (and also Mr. Enwezor’s leading Counsel). The Onoli is a man of peculiar consequence among certain sections of Onitsha and is often held in remarkable respect.”

- Portions of this brief account are drawn with thanks from the succinct summary written by his son, John Okechukwu Ibeziako, published in Akosa 1987;128-35. [↩]

- For some of his exploits, see Henderson 1972:474-7;487. [↩]

- Lugard 1937 [↩]

- For an historical account of this system, see Afigho 1972. [↩]

- Meek 1937:xvi [↩]

- ll679, vol XVI [↩]

- For fuller description of these OU-related activities, see the Chapter 2, page on “Cultural Politics and the OIU” [↩]

- For readers who wish to learn more about this work, try consulting Mr. Ibeziako Emmanuel, who says he is a grandson of the Onoli and hopes “to finish and publish the book”. He asks for more photographs of the Onoli. He may be contacted at ibeziakoce@gmail.com. [↩]

- Leith‑Ross, Sylvia, 1943, pp. 18‑19. [↩]

- See Henderson 1972; Bosah; Nzekwu; Chukwudebe; et al. [↩]

- See the West African Pilot May 13, 1940 for a report of the incident. [↩]

- I wondered if he was recalling his experience at the literary hands of Sylvia Leith-Ross. [↩]

- 1963:194. [↩]