1. Visitors learn: Ndi-Onicha, Ndi-Igbo

(Note that here I continue to render much of the text in the “present tense” of 1960-62.)

The first time I hear the word “Onitsha” comes from the voice of James Coleman1 in San Francisco in the Spring of 1960 (by way of suggesting I consider going there to do research), when he says, “…it is split right down the middle”. Igbo-speakers we subsequently meet in California in mid-1960 before we leave for Africa tell us this split concerns the opposition between “Onitsha Ibos” and the “non-Onitsha Ibos”. When we first meet Onitsha people, and hear them speak disparagingly of Ndi-Igbo (“Igbo people”), some explain to us in English that “We (Ndi-Onicha) are ‘Ibo’, but not ‘igbo‘,” though they accept that the language they speak is Igbo (albeit a distinct,”superior” dialect of that tongue). On the other hand, they identify only some of the non-Onitsha Igbo-speaking people with whom they interact as “Ndi-Igbo“, distinguishing other Igbo speakers as what I have previously translated as “Riverain” people” (Ndi-olu, sometimes called Ogbaru) or “Highland people” (ndi-enu-ani) (Igbo speaking people living west of the Niger), and denying that people of these categories are “Ndi-Igbo“(But in certain contexts they also label some of those people they call “Riverain” as “Ndi-Igbo“, as we shall see.)

This terminological complexity suggests considerable relativity in usage, and in time after our arrival in Onitsha we find that the distinctions can be sorted with some adequacy. At its broadest the term “Igbo” refers to a range of mutually intelligible language dialects, and it is this level to which “Ibo”, the early European rendering of the term, became a dominant reference form during the Colonial period, a designation of both the language and the people who spoke its various dialects (pluralized as “Ibos”). ( The confusion of spelling between Ibo and Igbo derives from the early failure of most European language speakers to grasp the distinctiveness of the implosive consonant later rendered /gb/ in linguistic texts.)

However, as a label for designating “people”, the term “Igbo” was historically employed by its speakers in much more relativistic and socially discriminating ways. From the perspective of some groups (mostly uplands dwelling, kingship-lacking Igbo speakers) it appears to have meant primarily a self inclusive “community of people” 2, while for other groups it meant a self excluding, distancing label for those Igbo speakers who lived on uplands east of the Niger, in “bush” or forest, people who lacked institutions of kingship, people who were taken as slaves, or people possessing some combination of these features (including other behavioral criteria) 3 .

In relation to these distinctions, the Onitsha people I interview in 1960-62 define themselves at two major levels of contrast. In relation to the other major ethnic groups currently contesting Nigerian politics, Ndi-Onicha class themselves as “Ibo” (vs. Yoruba, Hausa, et al). In this regard, they include themselves within Nnamdi Azikiwe’s 1940s newspaper political category of “The Ibo man”. But among those falling within this category, they distinguish themselves by a systematic self exclusion: they are definitely not “Ndi-igbo“, for them a distinctly pejorative term (often spoken with a sneer), nor (though they emphasize their close cultural and social bonds with “Riverain People”) do they class themselves collectively as “ndi-olu“: stereotypically, Onitsha people “cannot swim” (though some of their own sub-groups overtly identify themselves as “ndi-olu“) , and for some purposes and in some social contexts, they label some Ndi-olu as “ndi-Igbo“. Onitsha people, they say, are (in contrast) “Onitsha people” (ndi-Onicha), unique and apart from all of those immediately around them (and if they want to emphasize this difference, often label themselves “Children of God” (Ndi-umu-Olisa or Ndi-Umu-Chukwu).

This cultural separateness is rooted in dimensions of their legendary past. Nnamdi Azikiwe alludes to it in his autobiography, referring to a folk etymology of the term “Onitsha” said to be accepted by the widely-scattered people themselves: onini ncha, “to despise others”. When Zik asked his grandmother why Onitsha people are said to “despise others”, she replied to him that “because we belonged to the Royal House of Benin and that we regarded ourselves as the superior of other tribes because they were not connected with Benin Royalty… it was taboo for us to associate with others .”

A related perspective, which gives more sense of interactive attitudes, is given by the Onitsha author Onuora Nzekwu in his 1961 novel Wand of Noble Wood, where he writes:

“People from the Ibo communities around Ado (= Onitsha) and from those beyond, who have had the misfortune to exchange angry words with my people, regarded the Ado (ønye-ønicha) man’s tongue as his most effective weapon. They marveled at the impudence and the shamelessness of its face saving remarks. They invariably winced under its biting sarcasm. This last they found very exasperating, particularly when the tongue was a woman’s, for it lashed out with a sting that was too painful to bear…. Every Ado man was accomplished in the art of weaving and delivering sarcastic remarks. {This} …was the basis of the theory that the name Ado was derived from a much longer expression, which, interpreted, meant one who held everybody and everything in contempt.”

So it slowly becomes clear to us that, from Onitsha people’s perspective, there is a strong symbolic opposition between their own collective connection with royalty and the quality of “being Igbo“, though the full significance of this opposition remains murky, partly because of the slippery quality of the latter concept itself and partly because of an association of both with killing which is

somehow too horrifying at first for me to explore. While in Onitsha I had fewer direct contacts with Ndi-Igbo initially (our first direct contact, made in Berkeley, was an Onye-Onicha, Dr. Lawrence O. Uwechia of Isiokwe Village, and he very much helped to smooth our entry into Onitsha), the comments I hear when we first arrive in Onitsha at Independence time in 1960 from some of the Ndi-Igbo educated elite about their relationship to Onitsha people are suggestive: while expressing the highest opinion of Onitsha indigene Nnamdi Azikiwe as a national political leader, one young Onye-Igbo primary school teacher observes sarcastically that “Onitsha people have taken the wrong side of civilization”. On another occasion, an American trained Onye-Igbo university graduate remarks to me (to my baffled surprise as a newcomer) that Onitsha people “are not yet detribalized enough to enter the modern age.” This assertion, that a people who have achieved educational and professional attainments unparalleled anywhere else in Nigeria in proportion to their numbers, are “less advanced” in their “modernity” than he and his predominantly rural kith and kin points to a paradox I feel ill-equipped to understand.

The foremost ethnographic authority on the cultures of southeastern Nigeria, G.I. Jones, put it succinctly when he commented that since the first world war the Onitsha urban complex had become “the most important educational centre in the Region”, and that “(Ndi-Onicha) were quick to profit by these advantages and the list of famous sons of Onitsha… is staggering when one considers its small size” 4. I can only humbly echo these words, encountering among their numbers people who are in many ways better educated and more sophisticated than myself. I find myself wondering how it was I think I qualify to “study” them……

This paradox plays continuously in the pages of Onitsha’s Nigerian Spokesman newspaper, which is a vehicle of Zik, the “spokesman for the Ibo man”. Zik is a member of the late Obi Okosi II’s Sub clan, as is also the current Editor of the Spokesman in 1961 (J.A.C. Onwuegbuna). As simultaneously Ndi-Onicha and agents of the NCNC (the national political party of overwhelmingly Ndi-Igbo affiliation), they daily find themselves walking difficult paths as both supporters of “the Ibo man” and representatives of loyal Onitsha “sons of the soil”. But in 1961 the Spokesman is showing a strong (if mostly implicit) bias toward the latter and a subtly negative one toward the former.

2. Ndi-Igbo presence via the “Black Juju”

During the time when the fact of the Onitsha Interregnum is emerging in early 1961, Onitsha newspapers are also reporting an intense conflict within the Onitsha Urban County Council over the issue of the use in Onitsha Township of the “Black Juju” (iyi oji, “black oath/spirit”, so called because its widely feared Spirit wears black cloth), a power source residing in a large sacred grove in the nearby Ndi-Igbo town of Nkwelle. For many years during the first part of the twentieth century, diverse parties finding themselves engaged in irreconcilable disputes have brought this Oath out of Nkwelle and into various communities in the vicinity of Onitsha (and also in some cases across the Niger the the west), in order to resolve conflicts by magically sickening and killing the parties at fault (a death thought in this particular form to strike not only the primary disputants but also members of their families and over extended periods of time, an unusual persistence of power).

The Black Juju has gained great notoriety for its effectiveness in and around Onitsha, and its increasing reputation has led its Nkwelle proprietors to change the terms of the oath, which they make more devastating, i.e. to include confiscating victims’ moveable property for placement in the house of its shrine and charging large sums of money from those seeking to appease the Spirit.

For example, the Black Juju is called into an Onitsha Village by one party to an intractable intra-village dispute, the Nkwelle priest bringing into the accused’s house a small pot containing Egbo sticks (symbols of personal identity) from the Juju. The accuser and the accused meet in the presence of this power, the accused swearing his innocence while touching his lips to the sticks. With ordinary oaths, such an action contains a time limit for the effect to occur: for some oaths it may be 3 months, for others a year, but at the end of the designated time the accused (who has typically stayed in seclusion for fear of being surreptitiously poisoned) having survived, emerges in triumph, while the accuser must bring an animal sacrifice for all to share, and the case is closed. But this Black Juju oath has no time limits, so the relationship between the two opposing families is irrevocably altered.

According to a story repeatedly told me in 1961 (and referenced in newspapers and court cases as well), the Black Oath was brought against an Onitsha man (a Government employee native to Enu-Onicha) by his ex-wife in the late 1940’s. Subsequently, shortly after their son’s triumphal return from the United Kingdom as a newly-confirmed barrister, the young man died of a terrible skin disease, and his death was immediately interpreted as an act of the Black Oath. Nkwelle people came to the offending compound in Onitsha, charged the father the sum of £400 to appease the juju, and removed all of the deceased barrister’s law books together with his wig, gown, and chairs to the Black Oath’s Sacred Grove (where they were said to remain there, still on display).

As one Onitsha man said to me, “When the priest does the oath in the accused’s house, then that house is under Iyi-Oji: when anyone dies there, they can come and carry that house off brick by brick, and all its belongings.” ( The Nigerian Spokesman of August 28, 1957 reported a version of the story given by Mbanefo Odu before an Inquiry held by three Ministers of the Eastern Regional Government.)

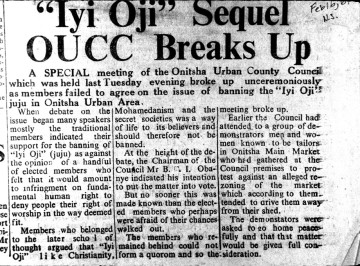

Since 1950, Ndi-Onicha acting as the conservators of “Native Law and Custom” on the Onitsha Urban Council (led by Council members who were Onitsha chiefs, Ndichie) have tried to ban the use of this Oath in Onitsha Township, but the issue arouses such heated debate that the conflict cannot not be resolved. On February 16, 1961, The Spokesman announces:

In this exchange, the “traditional members” refers to the Ndi-Onicha, the Obi and his OUCC-selected Chiefs, and Chairman Obanye is an Onitsha man, while “a handful of elected members” alludes to (mainly at any rate) Ndi-Igbo who oppose the proposed ban. A perhaps ironic component to this is the fact that the Obi and his chiefs strongly support their own rights to pagan worship, while most of the opposing councilors are emphatically Christian, and in ordinary conversation dismiss “pagan practices”. But they in effect “support” the juju because it seems to distress Ndi-Onicha folks.

This case illustrates a recurrent feature of the lives of Ndi-Onicha in 1961: the chronic if often unwilling dependence by some of their members upon cultural specialists living in contigous Ndi-Igbo comunities for traditional “pagan” services that have become largely unavailable within their own ranks. “We have lost these skills” from too much involvement in Western culture, they say, and when I ask them to introduce me to “native doctors” (ndi dibia)), they escort me to Awkuzu or to Nnewi or to some other nearby Igbo town where the most competent such people can be found. While there are “Jujumen” (and their Spirit Shrines) aplenty residing in Onitsha town, the powers of those in nearby Igbo communities hold much stronger respect in regional opinion, and many tales are told to me of currently-prominent Government leaders, holders of advanced university degrees, who in time of need express their dependence on some “bush” doctor for their personal welfare by traveling “incognito” into remote country villages to consult them. But the powers of the bush are feared most of all for their “Oaths”, which are employed to resolve conflicting claims of truth, and which strike with powers like those of the Mother Earth5 but whose influences are (in contrast) not limited to particular localities. The Black Juju can (and does) travel.

After the news about the Onitsha Urban County Council’s struggle with the issue of the “Black Juju” in February of 1961 I learn that James Abadom, an Onitsha man we have worked with (from Ogboli-Eke Village), has affiliations with people living in Nkwelle, and he agrees to escort Helen and me out to visit the shrine. (For a brief account of that visit, see below in this chapter, the Page entitled “Viewing the Black Juju….”)

That the Black Juju is by no means the only Oath of this type widely feared in Onitsha is evidenced from a top-headlined story in the Spokesman of June 19, 1961, reporting that a young woman (apparently the victim of a wild rumor concerning a ‘love deal’ exposed in the produce market) “was alleged to have brought to the market the powerful and most dreaded Abatete juju known as ‘Omaliko’, and “all the seed yam sellers who were panic stricken ran helter skelter….” The article concluded with the observation that, although the police have been questioning a number of witnesses, “the new device adopted by the woman was bound to cut a long matter short as the person involved would of necessity confess or take a costly risk.” ( Abatete village group is located east of Onitsha, beyond adjacent Ogidi. )

Use of such methods reflects a widespread African pattern of countering overt temporal power with covert spiritual strength (held by those less advantaged). While Ndi-Onicha (in their prominently prestigeful social positions at the time) are not the sole objects of such external means of social control, the issue of the Black Juju has clearly become a significant symbol of Onitsha Urban Council politics for a considerable time. Newspaper accounts from 1957 report three Eastern Region Government Ministers in Onitsha holding an inquiry whether the Oath should be banned for having “bad influence over people’s lives and property”, in which Isaac Mbanefo the Odu (Second Senior Chief of Onitsha Inland Town) claims that Ndi-Onicha are being “subjected to fraudulent extortion by the Nkwelles”, while one of his opponent chiefs testifies in opposition that such traditional “Oaths” “help to preserve the rights of common people”, serving to check “feudalism and oppression” .

3. More direct Ndi-Igbo presence: the Obosi Confrontation

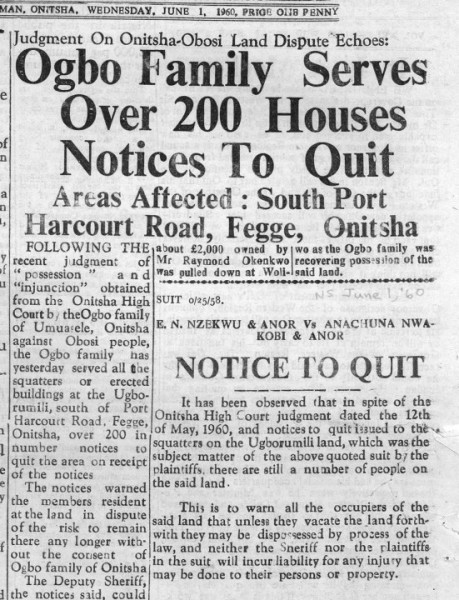

Of all oppositions between Ndi-Onicha and Ndi-Igbo in Onitsha town, the most publicly on display when we arrive in the Fall of 1960 is that involving the townspeople of Obosi, a community located immediately contiguous to and southeast of Onitsha and whose people recount in their oral traditions of precolonial times both periodic tributary relations to and repeated wars with Onitsha. 6 By 1960, following more than two decades of litigation between Onitsha and Obosi people over ownership and possession of farmlands on the south side of Onitsha, the Supreme Court of Nigeria and the United Kingdom Privy Council has awarded judgment concerning contested “Ugborimili” or “Otu Obosi” land in favor of the Ogbo family of Umu-Ase village in Onitsha, according them rights of both ownership and possession. This matter appears in the first Nigerian Spokesman we manage to collect, from June 1, 1960:

For the Spokesman, this combination of headlines — a banner headline trumpeting a court judgement for The Ogbo family (the Ndi-Onicha village of Umu-Ase) and against the Ndi-Igbo “Obosi people” regarding disputed land on the south side of Onitsha, along with a sub-headline presenting a “Notice to Quit” to those Obosi people identified as “squatters” on that land (signed by “C.E. Agbu LL.B Lond.”, solicitor for the Ogbo Family) — will recur in the Spokesman in the coming months. Several hundred members of the Obosi community are occupying houses of their own construction on these lands in the vicinity south of Port Harcourt Road abutting the Fegge Quarter of Onitsha Waterside.

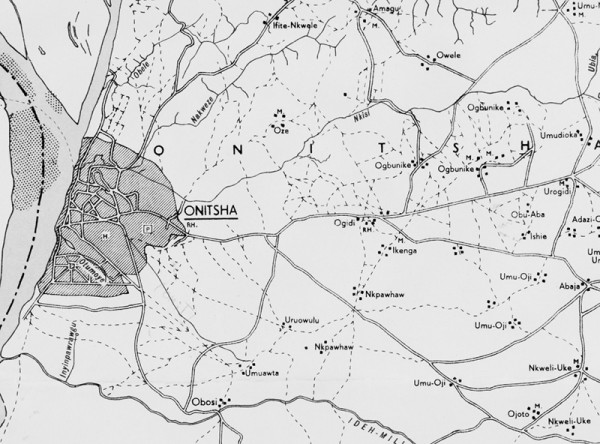

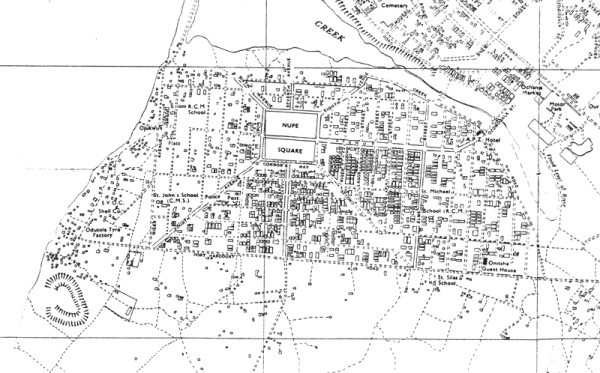

The 1957 official Onitsha map below shows the southwest side of the town around the then-new formal layout called “Fegge” (here unlabeled, but centering around “Nupe Square”, recalling the one-time “Nupe Quarter” located in this area, where traders from the Nupe-speaking Kingdom centering along the Niger in Northern Nigeria settled early in the century, later being relocated to make room for the new developers’ layout). “Port Harcourt Road” runs roughly east-west in the lower part of the image, from the Odutola Tyre Factory near the River to the “Onitsha Guest House” on the right.

1957 Map Otumoye, Fegge, Ugborumili

The scattered houses along the middle bottom of the map, below Port Harcourt Road (and which continue further to the south) are mostly those of Obosi people residing there at the time. Ogbo Family people regarded the “Ugborumili Land” (lit., “farms near the River”) referred to in the newspaper as running from the Otumoye Creek at the top to a point much further south than indicated here, indeed all the way to the Ide-Mmili (“pillar of Water”) Stream which flows freo east to west through Obosi:

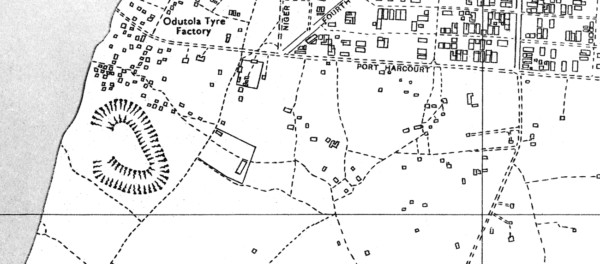

On this offficial map of 1958 (above), the Onitsha urban area is diagonally shaded, while the contiguous Ndi-Igbo towns are rendered roughly as geographically somewhat dispersed “village-groups”. In 1960, Obosi is politically the most salient of these towns, though the others (all Igbo-speaking) have many residents in the Onitsha urban complex as well, and play significant roles in relation to Onitsha. Noteworthy are the two village-groups of “Nkpawhaw” (spelled “Nkpor” in most texts), Umu-Oji, Ogidi, Ogbunike, Nkwele, and Oze. All these are significant neighbors for Ndi-Onicha.

Obosi people, in contrast, consider this southerly portion above the Ideh-Mmili to be part of Otu-Obosi (“Waterside-Obosi”), refering to a location occupied by the 19th-century Royal Niger Company during the years after the European establishments bombarded and then abandoned Onitsha in 1879, and established a substitute trading station there which they called. “Abutshi Wharf”, and which they used to bypass Onitsha in the palm oil trade at that time.

The RNC established some buildings there, and some of its agents occupied the location during the years between 1879 and 1900 (when they moved their locaation back to Onitsha). The exact location of the ‘whorf” is uncertain; by 1960, the houses on the coast were part of Ogbe-Ukwu, the “Great Village” occupied by people from Aboh (and other Riverine-linked comunities). In the map below, these are clustered directly above the circular “swamp”, while the “squatter” houses are those scattered in the spaces eastward from there and below Port Harcourt Road.

……………………………….

On June 3, 1960, the Spokesman trumpets the following Headlines:

HORRIFYING INCIDENT AT UGBORIMILI LAND

SHERIFFS AND POLICE BEATEN BY ANGRY MOB

CHILDREN AND HOUSEWIVES CRY FOR HELP:

200 HOUSES TO BE SEALED.

The accompanying article reports that an armed armed unit of Onitsha police, sent to Fegge, arrived there “with rifles and pistols” to arrest a “hostile mob throwing stones and bottles at the first batch of Police Constables” who had gone to the Ugborumili Land with the senior representative of Ogbo Family of Ndi-Onicha, who was authorized to take possession of 600 acres of that land (containing about 200 buildings) by the recent Onitsha High Court judgement. The mob was “alleged incited by one influential citizen of Obosi, still at large.”

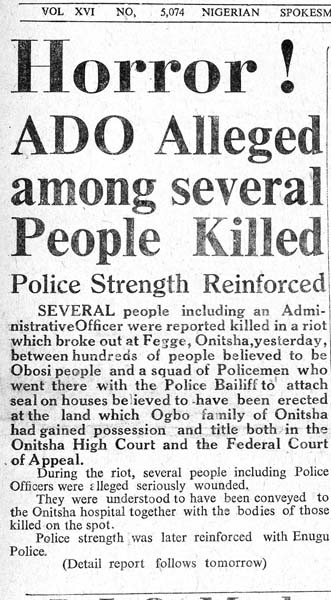

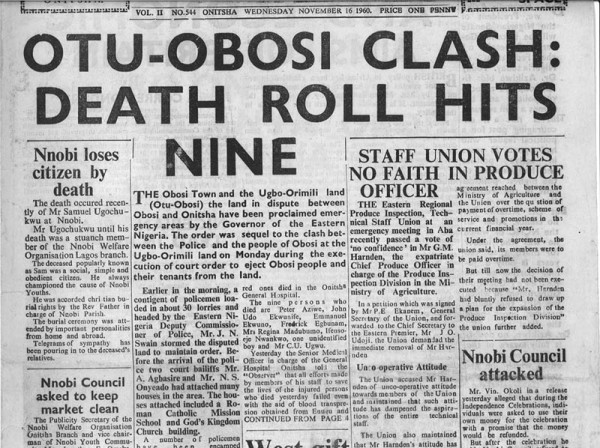

We arrive in Onitsha in late September, shortly prior to the Nigerian Independence Celebration of October 1, and are shocked out of our fieldworking complacency when the Nigerian Spokesman prints this banner headline on November 15:

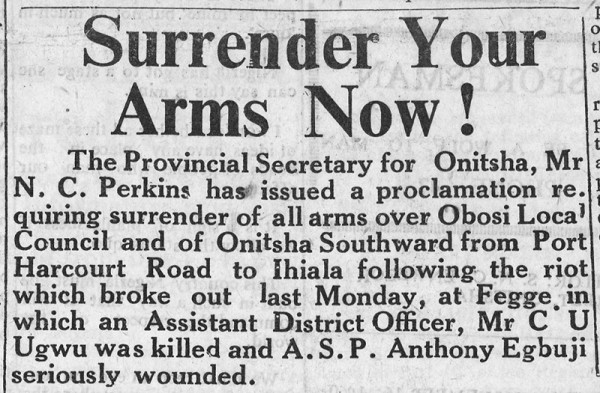

Note the implication that a large group of Obosi people are rioters, and the focus on injuries to the police (including the Assistant District Officer). On the next day the Spokesman prints this notice in the center of the front page:

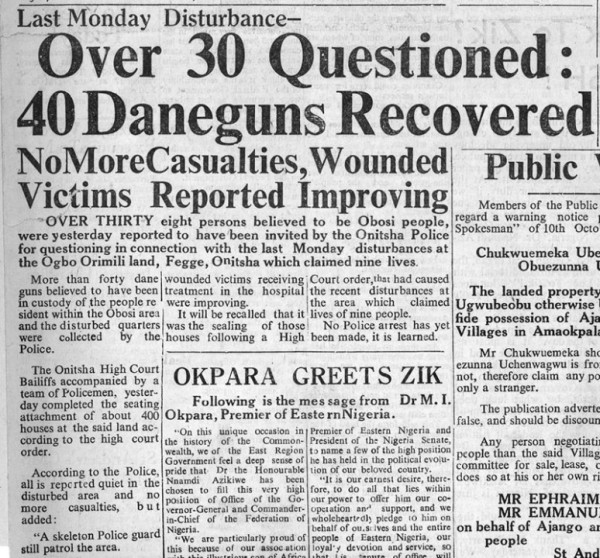

N.C. Perkins is a well-respected administrator, one of the last Europeans still occupying a top governmental post in the Eastern Region. The area covered by the Order would include most of the Obosi population not residing in Onitsha. On the 17th, the Spokesman focuses on the collection by Government of large numbers of “Dane Guns” owned by Obosi people.

So-called “Dane Guns” are flintlock rifles, widely imported into West Africa during the nineteenth century from various European manufacturers, and still widely used in rural Igboland in the middle of the Twentieth, though in most places largely for ritual purposes. At right, a member of the Aguleri Egbueni-Oba (Hunter’s Association) brandishes his before firing it at Obi Okosi II’s funeral in March of 1961. Many rural Igbo-speakers keep these guns and use them (often at funerals, but also occasionally for hunting purposes and self-defense). News reports occasionally report people killed at funerals, when these ancient gun barrels inconveniently explode upon firing.

While the Nigerian Spokesman (the official voice of the NCNC yet also that of Zik and hence his townspeople, Ndi-Onicha) focuses on the work of the police in corraling the rioting Obosis, the Eastern Observer, true to its persistent role of trying to strike a wedge between higher officials of the NCNC, and the current Eastern Region government it controlled — and the rank-and-file NCNC-affiliated Ndi-Igbo traders living in Onitsha, takes a very different stance, suggesting that the police opened fire on the Obosi people, killing and injuring some of them, and noting that Dr. J.E. Iweka, a notable Obosi M.D. who owns a hospital in Onitsha, had tried to help the injured.

Note that the very definition of the place in question has changed. “Otu-ObosiI” is “Waterside-Obosi”, the name given part of this area when Ndi-Onicha and the British 19th-century traders had a sharp separation and a marketplace was set up in this area and given that name.

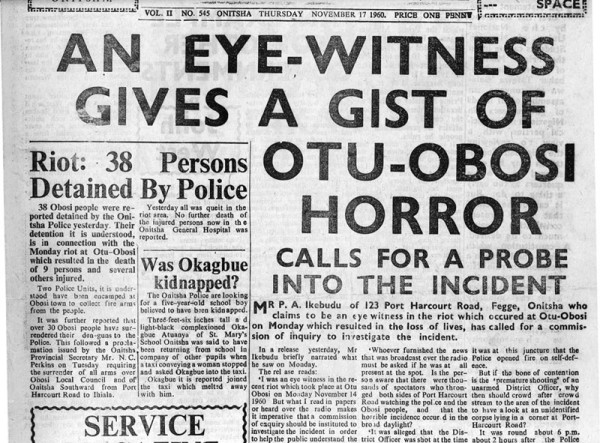

The Observer continues to build this model (the perspective of Obosi people) on the 16th, emphasizing the police role in “storming the disputed land”, naming the dead people, and noting that a church school and meeting hall has been part of the attached lands.

While later accounts of this November 1961 event are confusing and somewhat contradictory, newspaper reports covering the subsequent criminal investigations conducted by Government provide a basis for a (note well!) tentative narrative of the episode, which now follows.

As preparations are made by Government early in November to support the landowning Ogbo family of Onitsha in its efforts to expel the Obosi “squatters” from the land (some of whom have lived there for many years), two leading citizens of Obosi town, Dr. Jonas Iweka and Mr. Isaac Iweka, work to mobilize Obosi opposition to this move. Both men have attained considerable prominence in Onitsha urban affairs. Long ago their father purchased substantial lands in Onitsha Waterside, where Dr. Iweka has since built Central Hospital, a private institution located along the street now named Iweka Road near Fegge, aiming to serve the needs of the immigrant Igbo populace of the Waterside. Isaac Iweka is a Civil Engineer and former Provincial Engineer of the Onitsha Public Works Department (PWD), and is also a leading businessman in the motor parts industry.

Both men play prominent roles in the commercial life of the city, have actively participated in the Non-Onitsha Ibos Association mobilized during the 1950s, and have become so deeply opposed to Onitsha people that they have refused to join the NCNC political party, primarily because of the strongly Onitsha-biased leadership of that party (symbolized of course by its apotheosis of Nnamdi Azikiwe, an Onye-Onicha). Active in the United Nigerian Independence Party (UNIP) which has been formed to oppose Zik’s leadership of the Eastern Region Government during the late colonial 1950s (but is now mostly defunct), they more recently have become supporters of Dr. K.O. Mbadiwe’s DPNC (another party formed to oppose the dominance of Zik and Ndi-Onicha in the NCNC), and since much of Obosi town’s population have followed their political lead, Obosi now stands as a small but stubborn island of opposition to the NCNC in that party’s own Eastern Nigeria heartland.

Isaac Iweka apparently addressed the Obosi people in their town square on the eve of the Ogbo Family’s move to attach the houses at Waterside Obosi, and Dr. Iweka was present at the Fegge site early in the morning of November 14, 1960, when the first contingent of police arrived to mark the houses to be sealed. By 10:30 A.M. a crowd of more than a hundred Obosi women, dressed in ragged clothing (attire traditionally symbolizing readiness for combat) and carrying sticks, stones, and bottles, began dancing before the police, singing a war song, “Today we will die” (Tata ka anyi ga anwu), and shouting, “No! No!” (Mba! Mba!) in response to police statements. As more police arrived, officers were informed that several hundred Obosi men were hiding in the bush, armed with spears, machets, guns, bows and arrows. The crowd began chanting, “The police can leave; we seek Onitsha people!” (Ndi polis ga na, anyi choro ndi Onicha).

When the District Officer, B.C. Okagbue, began reading the Riot Proclamation commanding the crowd to disperse in the name of Queen Elizabeth II, voices from the crowd inquired if he was an Onitsha man, and when he replied yes, they began to ridicule and spit on him. When the Senior Superintendant of Police ordered a police advance to encircle the buildings, men hiding in the nearby bush greeted them with a rain of stones, bricks, and bottles. The police responded with tear gas, but the breeze off the river blew it back in their faces and, as many of the police scattered and ran, shots began to ring out. An Assistant District Officer was later found stabbed to death, 7 Obosi citizens were killed, and some 18 policemen and 30 Obosi people were injured in the melee.

Afterwards, the Governor of Eastern Nigeria declared the disputed land and the whole of Obosi town to be “Emergency Areas”, and some 30 lorries full of policemen drove in to establish order. The police seized substantial numbers of flintlock rifles and invited scores of Obosi people for questioning, as the Eastern Nigerian government began a preliminary investigation into charges of murder and riotous assembly. Dr. Iweka was accused of inciting a crowd to riot and Engineer Iweka of counseling a crowd to riot.

The investigation has formally opened in January 1961 and continues through the first half of the year. Both Onitsha newspapers carry fairly detailed summaries of court testimony during the traditional ritual month of prescribed silence following the death of Obi Okosi II.

Then, on June 2, after a long series of preliminary investigations and as Eastern Nigeria prepares for forthcoming elections to the Eastern House of Assembly, the Spokesman reports that the Premier of Eastern Nigeria, Dr. Michael Okpara, is planning to make an official tour of Obosi town, and that to mark his visit both Dr. Jonas and Engineer Isaac Iweka have declared they are joining the N.C.N.C., along with “all the Obosi people”. On June 5, a Spokesman editorial welcomes the Obosi declaration as “the beginning of a change that is to bridge the gap which has for a long time separated the (Obosis) from the popular camp of “national crusaders”, and emphasizes that NCNC supporters have the “duty to promote common understanding and to eschew clannish leanings and tribal loyalty for which the Action Group is notorious”. (The Action Group, AG, is the party forming the Opposition to the current coalition government.)

The same page includes the text of an Obosi community address (written under the auspices of the NCNC, Obosi branch) welcoming Dr. Okpara on the occasion of his official visit to their town, under the headline “Obosis tell East Premier ‘We are Law abiding'”. The speech concludes by drawing the Premier’s attention to some of the town’s urgent needs, including the “request that consideration be given to Obosi being accorded its rightful position by recognising their Eze, the Igwe of Obosi, as first class traditional chief.” (This would mean raising him to the same level as the Obi of Onitsha.)

By mid June the matter of the “Otu Obosi riot” has dropped from the newspaper columns, not to reappear as a significant theme during the remainder of our stay in Onitsha (though the Iweka brothers do do become involved in some later court dealings in relation to their roles in the affair). Obosi people may rationalize their entry into the NCNC embrace on the grounds that the new leader of this party, Dr. Okpara, is not the Onye-Onicha Zik (now politically much more remote, residing in Lagos and entrenched in his largely symbolic position as Governor General of the Nigerian Federation) but is instead very much an Igbo man (from Umuahia, in the extreme southeast section of Igboland), and who as the new national leader of the NCNC replacing Zik is cautiously but systematically rebuilding the party in his own image. Onitsha people express concern about this change in leadership: they wonder if Dr. Okpara has any commitment whatever to maintaining their historically privileged state in the Township, and Government’s current treatment of the “Otu Obosi” affair has worried the more thoughtful of them.

In midsummer of 1961, in response to my request to visit the old site of “Otu Obosi” (the riverside trading center occupied by the European mission agents and traders for some years after 1879 while Onitsha was in disfavor with the Royal Niger Company during that company’s years of dominance on the river, when the RNC redirected their trade toward Obosi people for the better part of a decade), my research assistant Byron Maduegbuna escorts me to the place (where I see a number of carved gravestones commemorating the deaths of Europeans from malaria in that location prior to the British return to Onitsha in 1900). As we approach this spot, the whole area south of Fegge layout appears to be firmly under the control of Obosi people: we are met at several points of the way by Obosi men (apparently standing as informal guards in the area), and Byron finds it advisable to speak with them in Obosi dialect (rather than that of Onitsha, so they will not suspect he has firm links with Onitsha people).

Thus right on the edge of the city, and in the midst of land “owned” by Onitsha people, Ndi-Igbo people are occupying and defending their space there, openly threatening Onitsha people with violent death and effectively barring them from the place they claim to be their own (backed up by the Federal Government of the time).

4. The Opposition is Stark (But Moderated)

And yet, at the heart of these mortal conflicts there resides deep ambiguity. When I talk with several men of Isiokwe Village (Onitsha Inland Town) in November of 1960 about the “riots” which have erupted at that time, I am surprised to hear them speak with great moderation about the relations between Ndi-Onicha and those of Obosi: the violence was not too serious, they smile, the rift in relationships will soon be repaired. Later I learn that the mothers of these men are from Obosi, and in a brief census of the Isiokwe residential area conducted during that time I discover that among elderly household heads, a considerable number have wives from Obosi (and from other nearby Ndi-Igbo towns), and I also learn that the village of Odoje (of which Isiokwe is a part) includes substantial sections which said to have migrated from the Obosi area. This means that many Isiokwe and Odoje men and women are “Daughters’ Children” (Nwa-Di-Ani, lit. Children-of-the-soil) to these nearby Ndi-igbo communities, and therefore their deepest social loyalties (not to mention those of their mothers and their mothers’ kin) are likely to be sharply divided.

The longer we stay in Onitsha, the more specific evidence we find of extensive historical transgression of Onitsha peoples’ sociocultural boundaries by Ndi-Igbo incursions (through marriage, pawning and domestic “slavery”, and other forms of social “invasion”). And yet in public social contexts, the “hardness” of these identity boundaries seems sharp and decisive to most people on both sides: while behavioral processes are very complex, the public categorical images of the Other are sharply, harshly drawn. Meanwhile, various social formations are “formed out of the bits and pieces of previous societies.”

- Author of the magisterial Nigeria: Background to Nationalism, 1958. [↩]

- Meek, 1937, p. 1, Oriji 1990, pp. 2-4 [↩]

- See Henderson 1972:40-41; Jeffreys n.d., 2:4-8,20, 6:24-27 [↩]

- In Jones The Jones Report… 195 , p. 27 [↩]

- Ani, see Henderson 1972:115-16,176-7 [↩]

- For example, see Henderson 1972:85-86,91-2. A detailed account of Obosi tradition may be found in Iweka-nuno 1924. [↩]