1. The Ajie presents “interesting history”: The Nigerian Spokesman April 20, 1961

[Note: Click on any image you may want to enlarge.]

Many readers in Onitsha Inland Town are surprised on this day to find an article in the Spokesman by Chief Mbamali the Ajie, entitled “Methods of Selection of Next King of Onitsha.” Accompanying the text is a large photograph of the Second Minister himself, grasping both leather fan and ceremonial sword, wearing his Great Tree Headdress, and facing the reader with a confident smile.

The Ajie begins his essay by recalling how the aftermath of the 1931-35 kingship dispute had resulted in a perpetual state of disunity in Onitsha lasting until 1958, “when the present Onowu was installed.” Wryly observing that “events since the illness and demise of His Highness Okosi II seem to indicate that we are returning true to type after a very short spell of unity and peace,” he argues that something must be done to avoid a repetition of the past. An amicable settlement could however be achieved “if elected leaders of all branches of Umu-EzeChimawill get together as members of one family, which rightly they are, to discuss and agree on the lines of succession and methods of selection once and for all time.”

The Ajie begins his essay by recalling how the aftermath of the 1931-35 kingship dispute had resulted in a perpetual state of disunity in Onitsha lasting until 1958, “when the present Onowu was installed.” Wryly observing that “events since the illness and demise of His Highness Okosi II seem to indicate that we are returning true to type after a very short spell of unity and peace,” he argues that something must be done to avoid a repetition of the past. An amicable settlement could however be achieved “if elected leaders of all branches of Umu-EzeChimawill get together as members of one family, which rightly they are, to discuss and agree on the lines of succession and methods of selection once and for all time.”

The appropriate way to pursue this aim, the Ajie continues, is to establish (1) who are the “accredited Umu-EzeChima“; (2) which “branches of Umu-EzeChima” are entitled to the throne; and (3) the “order of succession”: if rotational, between which branches, or if by election, whether each branch should present a candidate for said election. Once this has been done and the procedural sequence pursued, the “democratically selected or elected candidate” may then be unanimously presented to the Prime Minister for “proclamation and subsequent installation.” There would then ensue, says the Second Minister, “a reign of peace and prosperity “… which “…will nip in the bud the gathering cloud of strife and confusion which appears to stare us in the face.”

This opening statement is noteworthy (aside from its colorful array of metaphors) first of all for basic assumptions entirely different from those of the Enwezor group: that the entire Royal Clan (Umu-EzeChima) should gather to decide the kingship succession, and that they should “democratically” select (or “elect”) a candidate, then present him to the Prime Minister. So far the Ajie is acting as an agent of the Royal Clan as a whole, and stating its claim as formulated in the group’s meetings of March 25 and April 8. Secondly, there is the definite implication that the rules of succession themselves are not yet an established tradition but rather an outcome still to be constructed, by means of democratic decision-making procedures.

Having suggested “ways and means of effecting settlement,” the Ajie then seeks in the second part of his article to address what he has characterized as a problem of “accreditation”, or as he now puts it, to provide “some historical facts which will guide and enable the leaders of Umu-EzeChima in taking decisions,” and at this point his discourse shifts into a formulation of mythical chartered, sectional rights:

“It is generally accepted that Eze Chima came from the Benin ruling family who themselves emigrated from a ruling house in Ife in Western Nigeria. He was not destined to cross over the Niger which was his dream. He died on the journey and was buried at Isele.

“His brother Oreze continued the journey with his, Eze Chima’s children. They crossed over the River Niger and established Onitsha Chima.”

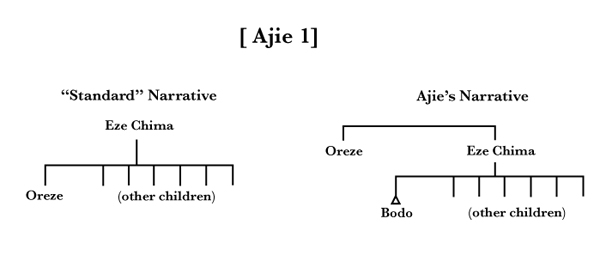

This text conveys a fairly standard version1 of the Onitsha legend of origin, except that the Ajie makes Oreze a brother to the founding hero whereas the more generally accepted versions make him a son (the one who by the clever trickery of concealing a royal drum in his canoe won the rights to kingship away from the other clans of Onitsha). Since the people of Okebunabo consistently trace their descent through Oreze in contrast to other members of the royal group, the Ajie‘s narrative has the effect of questioning their position vis a vis “the Umu-EzeChima” (i.e. the Royal Clan).

This text conveys a fairly standard version1 of the Onitsha legend of origin, except that the Ajie makes Oreze a brother to the founding hero whereas the more generally accepted versions make him a son (the one who by the clever trickery of concealing a royal drum in his canoe won the rights to kingship away from the other clans of Onitsha). Since the people of Okebunabo consistently trace their descent through Oreze in contrast to other members of the royal group, the Ajie‘s narrative has the effect of questioning their position vis a vis “the Umu-EzeChima” (i.e. the Royal Clan).

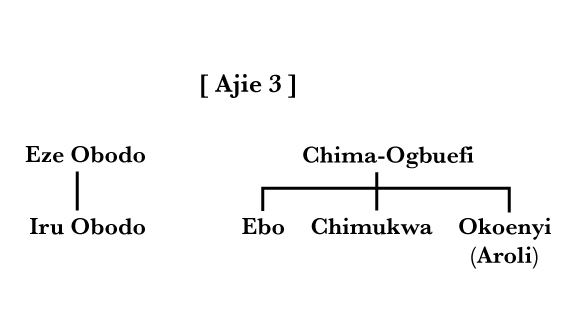

The next portion of the tale is printed in bold, large letters directly beneath the Second Minister’s photograph:

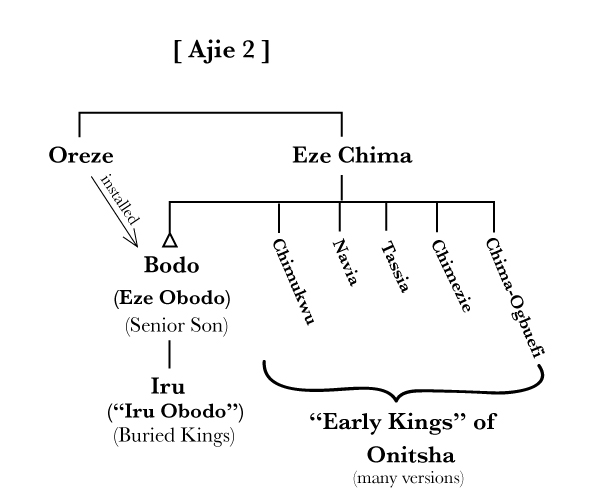

“Oreze installed Bodo, now called Obodo, first son of King Chima who had all his father’s paraphernalia for kingship, the King (Obi) of Onitsha Chima. He has always been referred to as Eze Chima the founder of Onitsha Chima. This has been responsible for his name Bodo going into oblivion in the list of Kings.”

Here of course the Ajie inserts a version of the story he had outlined to Byron and me some time earlier. This is the keystone of his case for the Children of Olosi having an ancestral King (rather than a Daughter) as the founder of their lineage.

Continuing his narrative, the Ajie links this assertion into a standard version regarding succession of the Onitsha early kings, and combines this with further data:

“When he (Obodo) died Chimukwu, Navia, Tassia, Chimezie and Chima-ogbuefi (Cowkiller) took the throne in succession.

On the death of Chimukwu who reigned next after him Iru, the son of Obodo Eze, who was the first to bury a king and therefore knew everything connected with the funeral ceremonies was invited with his children to bury the king.

They also inherited the king’s property as Senior Lineage Priest.

This tradition is still maintained until this day with modification.

Now instead of inheriting the King’s property a few of his personal belongings were accepted in token thereof.”

Here the Ajie presents some further transformation, accomplishing several things. It connects Eze Obodo with the succession sequence I have elsewhere called the “Early Kings,” a list given variable genealogical relations but invariably presented at this primordial stage in Onitsha royal genealogies2 Second, it then provides an explanation of Umu-Olosi‘s traditional specialized duties at the burial of the Onitsha King by defining their role as Senior Priest (Diokpala Umu-Eze-Chima), rather than as “collective Senior Daughters” (Isi-Ada) of the Royal Clan. Use of the name “Iru” facilitates explaining the traditional “Face of the town” (Iru Obodo) appellation accorded to this group as a combination of the names of its two founders, rather than as a result of the group’s having been placed at a frontier location in the community. 3

Here the Ajie presents some further transformation, accomplishing several things. It connects Eze Obodo with the succession sequence I have elsewhere called the “Early Kings,” a list given variable genealogical relations but invariably presented at this primordial stage in Onitsha royal genealogies2 Second, it then provides an explanation of Umu-Olosi‘s traditional specialized duties at the burial of the Onitsha King by defining their role as Senior Priest (Diokpala Umu-Eze-Chima), rather than as “collective Senior Daughters” (Isi-Ada) of the Royal Clan. Use of the name “Iru” facilitates explaining the traditional “Face of the town” (Iru Obodo) appellation accorded to this group as a combination of the names of its two founders, rather than as a result of the group’s having been placed at a frontier location in the community. 3

Continuing his essay by evoking the oral tradition associated with King Aroli, the Ajie relates that:

“Chima-Ogbuefi had three children namely, Ebo, Chimukwa and Okoenyi (Aroli).

Ebo also did not want to reign and both he and Iru Obodo wanted the throne retained in their maternal family lineage and so decided to proclaim Okoenyi King even though he was a minor.”

This passage establishes a distinctive relationship among Iru Obodo and the ancestors of the Isiokwe group (Ebo and Chimukwa). 4, and with King Aroli, these latter figures forming the well-known cultural charter previously outlined. But Ajie‘s version centers around the fact of Aroli‘s juniority to the others, and his having been “sent to Igala” for a period of time prior to being installed as King.

In the Ajie‘s version here, Ebo and Iru Obodo, fearing that their junior brother might be killed in his home town, first sent him off to Igala (his mother’s home), then foolishly retrieved him and made him King of Onitsha. When Ebo and Iru Obodo “summoned the Umu-EzeChima and declared their intentions “to make him King, members of the Royal Clan retorted: “When will Okoenyi come of age?” (“Kedu Aro Okoenyi Geji We Me Madu“). ( This particular question is part of a generally accepted account among Onitsha elders, the meaning of which is uncertain to me. 5

Later, however (the Ajie tells us), having accepted Aroli as their king, the rest of the Royal Clan found to their chagrin that Aroli‘s descendants “repulsed vehemently any attempt by other ruling houses to regain the throne.”

The Ajie goes on to maintain that it was because of this subsequent selfishness on the part of the Umu-EzeAroli that the Umu-Olosi later bestowed upon the Ajie‘s own great grandfather Obijioma (who was the Fifth Minister of Onitsha during the late 19th century) the title of Eze Oba (a combination of both Benin and Igbo highest Kingship titles), and that Eze Oba later conducted his own Ofala (Festive Emergence) ritual in an attempt to regain the throne for his people. This heroic struggle by his great grandfather against King Anazonwu, the Ajie affirms, helped prepare the Onitsha people for breaking the chain of Umu-EzeAroli successions in 1900. 6

The Ajie then concludes his long (and rather complicated) argument by observing that:

“it is pertinent to note that the descendants of Obodo Eze and Chima-Ogbuefi maintained their affinity up to a time.

This affinity was reflected in their oneness in Ozo title taking.

Owing to increase in population and changed circumstances the descendants of Eze Aroli branched off leaving the descendants of Eze Obodo and those of Eze Aroli’s elder brothers, Ebo and Chimukwa (i.e., ancestors of Isiokwe), to continue the relationship until this day.”

This final statement deals with known facts that the people of Isiokwe and Umu-Olosi share Ozo title-taking money as a unit today, and that they both formerly did so with Umu-EzeAroli until (sometime in the nineteenth century) an Ozo money dispute separated the two groups in this activity. What the Ajie contributes to this last oral tradition is an effort to explain these facts by demographic and other sociological factors (rather than by taking account of royal genealogy, since the Obodo model makes Isiokwe and Aroli genealogically closer to each other than either is to Olosi).

So the second part of the Ajie’s article addresses his problematic of Who are “accredited” members of the Royal Clan. In this section he manages to (1) cast some aspersions on the royal legitimacy of Oke-BuNabo, (2) diminish the stature of Umu-EzeAroli by emphasizing their juniority (including here an implication of foreign taint, all of which is valid cultural history) and later “unfair monopoly” of rights to the throne, (3) explain away the imputation of maternal ancestry in the genealogy of Umu-Olosi, (4) explain certain distinctive features of their social connections with both Umu-EzeAroli and Isiokwe without genealogical reference, and (5) identify the Umu-Olosi as a long stalwart segment of the Royal Clan continuously engaged in a struggle to retake a throne which had been unjustly expropriated from them. In all these accomplishments, he cites no external authority but simply asserts his version as truth.

2. Okebunabo spokesman J. Orakwue rebuts

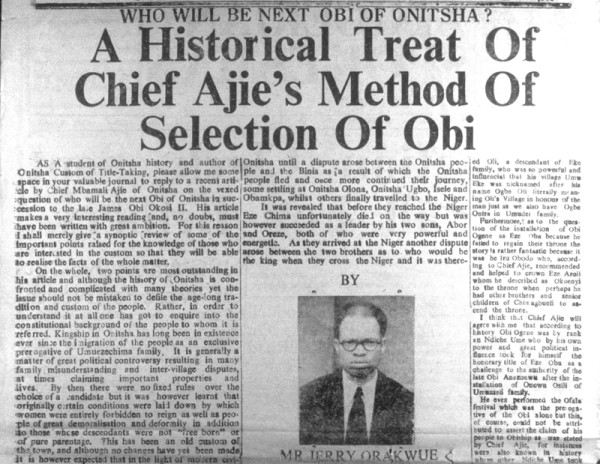

Jerry Orakwue, a self-appointed voice spokesman for Oke-BuNabo who earlier commented to me on the Ajie‘s article by saying, “Well, it looks like we may be having some new history in Onitsha”, now presents his own “Historical Treat of Chief Ajie’s Method of Selection of King” in the Nigerian Spokesman of April 25.

Beginning with the observation that Chief Mbamali’s article “makes a very interesting reading and, no doubt, must have been written with great ambition,” Orakwue observes that “Kingship in Onitsha has long been in existence ever since the immigration of the people as an exclusive prerogative of Umu-EzeChima family,” and proceeds to say that:

“According to history the selection of any candidate was never a concern of any one particular family or group of people but the affair of the town in general decided by the majority wishes of the people hence the award of the title is generally described as ‘Eze Bu Ira Nyelu’ meaning a King is an award by the whole people.”

Thus his preamble in effect parallels a major point made by the Ajie, though stating it in the more general sense as part of a prominent Onitsha proverb contrasting succession to kingship with that to senior priesthood 7 and which clearly affirms a tradition of popular participation in the selection process.

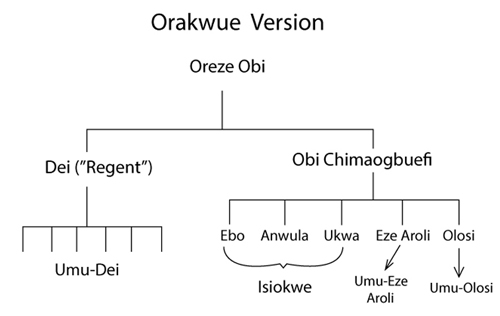

In the second part of his essay, Orakwue’s version of the origin legend begins with the travels of Onitsha people from Egypt, “along with the Ashantis, Yorubas, and Binis,”8 and then focuses in on the founder of Onitsha town, Oreze:

“Oreze the King, it was learned, had sons, Dei and Chima-Ogbuefi, who later succeeded him to the throne and whose descendant(s) now form the main bulk of Umu-EzeChima families.

“Dei whose descendants at present form the Okebunabo families was said to have died as a Regent and was therefore succeeded by his brother, Chima-Ogbuefi, who had four children namely Ebo, Anwula, Ukwa, Aroli, and a daughter who was married to Ugbum and whose descendants it was stated now form Ogbe-OliOlosi.”

Part of a more standard version of the origin tale, this one re-designates the Ajie‘s lineage as descendants of a daughter (as the Ajie himself had earlier stated when I spoke with him in January before Obi Okosi II‘s death), and also nicely places the Okeb-buNabo ancestor “Dei” as one of the two royal children of the founder- King (though evading the issue of Dei‘s own kingship by suggesting he “died as a regent”):

To bolster his own genealogical account, Orakwue attacks the Ajie‘s construction of “Obodo” (or “Bodo“) asking two rhetorical questions:

“If…Obodo was the first son of Eze-Chima and the first King of Onitsha…why was Obodo succeeded to the throne by Chimukwu the son of Dei instead of his eldest son Iru, who was entitled to his father’s regalia?

Again, if Iru was the eldest son of Obodo the first king of Onitsha and son of Eze-Chima who were the other children of Obodo and what families in Umu-EzeChima do they represent?”

As clinching evidence for the “true” genealogical position of Olosi that the Ajie had ignored, Orakwue points out a logical inconsistency in the Second Minister’s account:

“I am happy that Chief Ajie was able to realise the affinity that existed between his people and the other members of Umu-Chima-Ogbuefi in the custom of Ozo title taking merely because they descended from one ancestor.”

The explanation for the Ozo sharing relationship is thus returned to a pattern fitting the standard genealogical history.

After briefly elaborating on the Olosi role as “descendants of the daughter of Chima-Ogbuefi,” and discussing the origin of their village name (Ogbe-Oli-Olosi), Orakwue proceeds to attack the Ajie‘s glorification of his Great grandfather Ogene EzeOba, pointing out that the latter’s seizure of certain kingly prerogatives represented not an ascension to Kingship but merely a “challenge to royal authority” over his disagreement with a reigning King,

“…for instances were also known in history where other Ndichie-Ume (Senior Chiefs) took to themselves titles of Kingship and even celebrated the Ofala festivals in demonstration of their protest and rivalry against the attitude of the Obi over certain matters.”

Witness, he says, the late Odita Ajie of Ogbe-Ozala (High-Grass Village), who assumed the title of Nkisi (identifying him with the sacred Nkisi Stream on the northern borders of Onitsha) and acted like a King in conferring Ndichie-Ume title upon Chima of Ogbe-Ndida (Low-Village) during the reign of Okosi I. Witness the late Okechuku Ogene (Fifth Minister) of Children of Dei, who “performed his own Ofala (Emergence festival) in protest against the alleged maladministration of the late Okosi I.” (These were all fully historical events, not subject to informed denial.)

Thus in his brief rejoinder Orakwue manages to (1) agree with the Ajie about the primacy of the Royal Clan in deciding kingship succession and the importance of “the majority wishes of the people,” (2) reaffirm the royal legitimacy of Dei as a son of Eze-Chima and as the founding ancestor of Oke-BuNabo, and (3) reassign the Umu-Olosi to a subsidiary role as Daughters in the Royal Clan, also casting doubt on the putatively “kingly” behavior of the Ajie‘s own great grandfather.

In contrast to the Ajie, Orakwue grounds his versions in repeated though vague allusions to “historical authority” (“…according to history”, “…it was said that….”), in part perhaps hinting about the contents of his own still unfinished book. ( These sources were written reports, including some from various elders preceding him. Jerry once brought forth to my view his manuscript on the broad history of Onitsha. Unfortunately, this manuscript seems to have vanished, probably as an outcome of the Biafra War. Regretably, I never had an opportunity to read it, and it probably contained carefully collected material no longer available in contemporary social memory. Orakwue was a genuine scholar despite his educational limitations, and he never received the full admiration he deserved.)

3. The Ajie responds

April 29, 1961 …………… (The Spokesman)

Denying any “great ambition” on his part, the Second Minister states that

“as the political head of Umu-EzeChima, I simply did my duty in calling for peaceful settlement so that the unity we are now enjoying may remain unimpaired. It is gratifying to observe that a conclave of representatives of Umu-EzeChima has been formed and God helping us we shall succeed in handling the matter satisfactorily.”

Regarding recent aspersions on the accuracy of his history, the Ajie doubts whether Orakwue has gotten “his own version right from his ancestors”, states that “none of us can claim to be an authority in an unwritten history of Onitsha,” and infers therefore that questions of truth must be worked out among a “reading public”, over such questions as:9

“Whether there was a king called Eze-Dei and whether the word ‘Dei‘ does not mean a prince and the man Dei a prince from Aboh Chima who having fallen out with his people sought for shelter and settled with his kith and kin in Onitsha Chima.”

(The definite cultural distinctiveness of Umu-Dei was another of the many ambiguous cultural features of various sub-groups within Ndi-Onicha There were very prominent Umu-Dei in Oguta town (which has a strong Ndi-Olu connection with Onitsha), for example.) 10

He then attacks the doctrine that Umu-Olosi are “Daughters” of the Royal Clan, pointing out that in ordinary burials the Daughters of the lineage are not the ones who prepare the grave and bury the dead (in fact, the Umu-Ilo “Youths of the Village Square” do these tasks). And why do Umu-Olosi,share Ozo title money with the people of Isiokwe, he inquired; is that something that Daughters do?11

The Ajie concludes his rebuttal by arguing that:

“the name ‘Ugbum’ and the idea that Umu-Olosi are Daughters to the Umu-EzeAroli were mere propaganda stunts originated by late Chima of Ogbe-Ndida (“Low Village”) during the protracted land case of 1914 to 1918 between Iru Obodo Eze and Children of King Aroli. Prior to this there were no such insinuations.”

In sum the Second Minister’s reply continues to (1) legitimize the importance of the Royal Clan meetings while (2) countering Orakwue’s aspersions against his Umu-Olosi genealogy with a tit-for-tat exposé of Orakwue’s own major village, Umu-Dei”, by proffering the well known claim that their founder was a refugee prince from Aboh (thus implying that their claims on Onitsha kingship are not first rate), and (3) defending his own group with the claim that the “Daughter”status attribution to Umu-Olosi is a recent vintage fabrication and inconsistent with relevant culture-pattern facts.

4. Some tactics of renegotiating oral traditions

These interchanges between the Ajie and Jerry Orakwue nicely illustrate how Onitsha people construct and manipulate oral traditions to make legalistic briefs concerning contemporary social legitimacy and rights. Each writer employs a point-for-point logical reasoning between each putative incident in the oral tradition and contemporary custom in order to judge the validity of his opponent’s narrative. For example, the Ajie argues that if the Umu-Olosi were actually “Daughters” of the Royal Clan, they would perform exactly the same roles as do Daughters in Onitsha descent groups, whereas in their actual roles of burying the king they also do tasks that are in normal funerals assigned to the Village Youths. Orakwue argues that if Iru, the putative eldest son of King Obodo, was in fact entitled to “the king’s property” after his death as the Ajie had claimed, why then did not Iru succeed his father as king? Why did a man from Oke-BuNabo succeed instead?

Thus the interpretive procedure is in each case to trace the opponent’s narrative along lines of strictly literal logical consistency with a specific traditional feature, until some discrepancy is found with current cultural practices, and then discount the narrative in light of the discrepancy. This appears to be an effective tactic in some cases, for example where Orakwue asks who are the other children of Iru if Iru was the “senior son” of Obodo, and why do Umu-Olosi and Isiokwe share Ozo title money apart from those of Eze-Aroli (if the “Children of Obodo” are separated from both of them). The Ajie does not reply. It is less effective where the cake of custom is demonstrably quite complex and ambiguous for example, where Orakwue asks why Iru the son of King Obodo did not succeed him (since there are plenty of accepted accounts of lateral succession in the oral tradition), and where Orakwue cites examples of other senior chiefs besides the Ajie‘s grandfather performing Emergence festivals in competition with their kings. In both cited cases one might readily make a different interpretation of the examples than his.

In general, each debater uses a literal interpretation for assessing his opponent’s accounts, with no allowance for metaphorical extensions of custom, but infers metaphorical transformations in presenting his own account, as the Ajie does where he argues that his people, as (putatively) Senior Lineage Priest to the Kings, inherit only “a few of his personal belongings in token (of his property).” I have found this mode of debating quite typical in works of “historical production” such as these.

A final noteworthy feature of both methods, however, is their negotiating the outcome of interpretation itself. Neither forecloses the outcome, each appeals to the reasonableness of his own argument to ground its evaluation. Especially in the Ajie‘s perspective, there is a sense that interpretation must be opened to something like a democratic negotiation process, which each writer regards as now under way.

5. Obiekwe Aniweta transforms the dispute

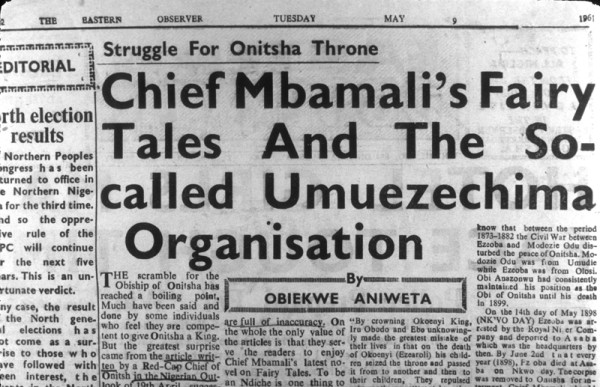

I discuss these newspaper articles briefly with my new social contact Aniweta, who responds by ridiculing the Umu-EzeChima meetings and adding that many of the participants are not genuine members of the Royal Clan. He says he is busy writing an article on the subject, which I will soon have an opportunity to read. He submitted this article to The Spokesman, which he tells me had promptly rejected it. 12, But he knew that the oppositional Eastern Observer newspaper would be willing to air the internal disputes of Onitsha, so he takes his article there, where it appears under the Editorial page Headline13

Noting that since the publication of the Ajie’s article “Onitsha was in a state of excitement,” Aniweta begins his discussion with a sustained attack on the person of the Second Minister, saying that “The Ajie of Fegge” (an allusion to the chief’s residence, not in the midst of his people in the Inland Town as custom woud decree, but among “foreigners” in the Waterside) “has decided to invent his own history of Onitsha,” and pointing out the Second Minister’s own personal interests in the succession itself:14

“Chief Mbamali is inordinately ambitious. He submitted his application to the Prime Minister of Onitsha (Onowu) Chief Anatogu, revealing his ambition to become the next Obi of Onitsha. I am not against anybody being ambitious, but ambition should be made of sterner stuff.”

Concerning the chief’s “school boy history,” Aniweta suggests however that:

“Chief Mbamali should be given latitude for his intelligence and for the fact that he has never read The History of Onitsha written by his senior cousin and an authority on Onitsha History, Chief M. Ibeziako, the Onoli of Onitsha.”

As we have seen, by 1961 a Ranking Chief of Onitsha, Ibeziako (a Daughter’s Child to Enwezor’s family, earlier observed attending the latter’s Ima-Nzu) enjoys a prominent reputation in the Inland Town dating from his years during the 1930s in the Onitsha Resident’s Office when he acted as interpreter for the Anthropological Officer C. K. Meek and also first held the post of Secretary in the Home Branch of the Onitsha Improvement Union during its formative era of development beginning in 1933-35. Since he and the Ajie are fairly close lineage mates, Ibeziako’s own brief pamphlet on Onitsha tradition can (Obiekwe suggests) serve as a check upon the Ajie‘s oral tradition. Citing Ibeziako as “a scientific and academic historian” who should be relied upon, Aniweta notes the conspicuous absence in Ibeziako’s king list of any King named Obodo, and opines:

“In the annuals of Onitsha such strange names Iru, Obodo, Bodo, Okoenyi have no place…. It is most unfortunate that a Senior Red Cap Chief of Onitsha should be subject to hallucinations on this point.”

Turning then to the significance of the Royal Clan meetings currently being held in Onitsha, Aniweta writes:

“But Chief Mbamali is not yet satisfied. He is the Chairman of the so called Umu-EzeChima Association and has even arrogated to himself the title of ‘political head of Umu-EzeChima’…. I have been attending the meetings as an observer.

Umu-EzeAroli an influential section of Umu-EzeChima is not being represented in the meeting since the Onya of Onitsha, Chief Muonweokwu Egbunike and Chief Chude, Adazie Ogulani (who is Aroli himself) have not (been in attendance).”

Chude the Adazie being the Senior Lineage Priest (Diokpala)of Umu-EzeAroli (and therefore “Aroli himself”), and the Onya the Senior Chief of that group, their absence does of course raise questions concerning the legitimacy of Umu-EzeAroli representation in the meetings of the Royal Clan. (Since both are committed supporters of Enwezor they appear to have no intention of attending these meetings, where their seniority would most likely be overridden by others, and they would thus become subject themselves to decisions arrived at there.)

Citing Orakwue’s statement that the “Whole People” of Onitsha traditionally select the King, Aniweta employs this point to undermine what he calls the “locus standi” of the “so called Umu-EzeChima Association,” maintaining that

“The selection of a king is the affair of the whole town. It is futile for any section of Onitsha to arrogate to itself the exclusive right of selecting the Obi of Onitsha.

“Any attempt on the part of any organization or group of people to disregard the influence of Ugwu-na-Obamkpa (i.e., the Non- royal Clans) as far as the present issue is concerned will result in adverse consequences.”

In these passages Aniweta strives to suggest that the non-royal clans would surely refuse to accept the imposing of a king by the Umu-EzeChima. Since the current Prime Minister is a member of the Non-royal group, the statement may also be construed as supporting the latter’s position and implying that the Royal Clan is planning to ignore non-royal input.

Aniweta concludes his article by returning to an attack on the Ajie. First he inquires whether it is proper for Mbamali, as a candidate for the throne, to preside over the Royal Clan meetings, thereby acting as a judge in his own case. Secondly he suggests that if the Second Minister is indeed a genuine candidate, he should return his Senior Chieftaincy Cap and Ceremonial Sword to the Prime Minister, in other words give up his chieftaincy. He concludes his essay by reminding the Ajie of “the story of the greedy dog:”

“A greedy dog was passing through a river. The avaricious dog had a piece of meat on his mouth. He was deceived by his shadow for he saw his shadow carrying a piece of meat. He pursued his shadow to get the other meat. The one he was carrying fell into the river. He left the scene without any piece of meat again. I don’t know if the Ajie could comprehend the moral of this story.”

Later, Aniweta expresses to me pleasure with his article, asserting he has delivered the Ajie a devasting blow. In this context, he appears to envision himself as a lone warrior striving single handedly to bring down a powerful and established chief. Secondly, he confirms to me this is part of his broader plan to turn both the Prime Minister and the other people of Ugwu-Na-Obamkpa against the Royal Clan Meetings. Aniweta appears to sense he has found a strong role for himself to play in the Interregnum conflict, .

The issues at hand

In my Onitsha experience, publicly harsh personal attacks of this kind are unusual within the context of Inland Town politics, though the Nigerian Spokesman occasionally prints even more venomous articles on politics at the regional and national levels, particularly against the Action Group political party (the Yoruba-based source of the local Eastern Observer) and various of its members (and those of similar minds). The Eastern Observer, which published Aniweta’s article, was normally more circumspect in view of its precarious legal standing in relation to the Eastern Region Government, but in this instance their publication of such an assault by an Onitsha indigene and NCNC member may provide a convenient way to present opinions they cannot not themselves safely voice (and which might serve to intensify embarrassing dimensions of conflict within the ranks of the NCNC, of whom the Ajie himself is a prominent local supporter).

I am puzzled at first by the brashness of Aniweta’s personal assault on so prestigious an elder, which includes imputations of callow ignorance of tradition, dishonest fabrications, stupidity, and even psychosis. When I ask Jerry Orakwue if this kind of confrontation by a young man has precedent in Onitsha tradition, he responds in measured but emphatic words:

“In the old days we did not hobnob with the chiefs as we do now. When I was small, no man ever spoke out of rank at a public meeting. Not that he wouldn’t speak strongly if he had courage, but he would wait his turn. If you were Those Who Support and Dignify, you wait until Senior Chiefs, chiefs, and if not titled until the Ozo men have spoken.

When I was small, and the Senior Chiefs came along this street, you would hear the bell announce their coming, and parents would call their children into the house, everyone would run away. Only a middle aged man, if he had courage and knew himself, could stay.

The fact was they could harm you, kill you just to show their power. Even today, when they dance they wear things to protect themselves and to harm others. But other men would clear the way when Senior Chiefs were dancing. It is only today that you find young men challenging these elders.” 15

There is, I had learned, the tradition of the Orator Spokesman, the courageously articulate untitled man who might challenge anyone, but such men generally hold the status of elders, and Aniweta is not at all viewed in that light. Aniweta however regards himself from a quite different perspective, as a modern confrontational political agitator, and he is not attacking the chiefs as such but the personal character of one of them. That he finds the Ajie uniquely vulnerable is suggested by his epithet “the Ajie of Fegge” (i.e., of foreignness), and the aim throughout appears to be to devalue not only his motives but his character.

However, Aniweta is here operating in a primary social setting whose standards of discourse are different from those of the national context, and everyone in that context knows Aniweta’s own genealogical and occupational affiliations with Enwezor.

His own behavior thus reinforces a view of him in the Inland Town context as one of those excessively assertive and irresponsible youths who “excel in anger” and who therefore are to be anticipated, dealt with carefully, and insofar as possible isolated at any serious gathering. While Aniweta hopes for further combat via news release, at their next Royal Clan meeting the members first consider this path but end by criticizing those members who had participated in the game (including the Ajie himself), and their conclusion of the affair takes the form of a resolution mandating subsequent media silence.

However, this interchange has now made public several major issues that will become important in the days ahead. There is the question of primacy as kingmakers: should Umu-EzeAroli, or Umu-EzeChima, , or the Onowu (Prime Minister) and other chiefs have the dominant voice? There is the question of the balance between Royal and non-royal clans: how much voice should the latter have in deciding who would be king? There are issues of legitimacy and rights of succession among the various subdivisions within the Royal Clan oppositions involving at least Oke-BuNabo, Umu-EzeAroli, Umu-Olosi, and Isiokwe,, but potentially other groups as well.

And in all of these matters there is a continuing question: what traditional pathways might be “followed” by people whose backgrounds have been so pervasively influenced by the “modern” (traceable back at the very least to the appearance of the first missionaries and traders at the Onitsha Waterside in 1857)? None of the main characters in the conflict can be regarded as a “truly traditional” figure, yet for all of them a symbolic emphasis on following traditional routes to the Kingship is stated to be paramount. The problem is in part to establish what routes are “truly” (or in current social-scientificcal terms, “hegemonically”) traditional, or perhaps if the pathways have become entirely overgrown, to carve something radically different out anew. Some people involved in the contest do appear to assume that the mass media will have a considerable role to play in deciding the outcome of this process.

6. Some Cultural Entrepreneurs of the Inland Town

When I first re-establish contact with Obiekwe Aniweta, the young ex teacher who as a member of Enwezor’s own village (Umu-Anyo) has previously agreed to work with me on a census of his village (in the context of the presence of Ikenna Nzimiro, a suitably “radical” figure in the eyes of disillusioned youth like Aniweta himself, At this point in the Inoutset of Interregnum, I now think it sensible to begin pursuing that task. In this way, I reason, I can both continue my research into Inland Town residence patterns (which had been displaced at the beginning of this “New AGe”), and simultaneously get to know more people connected with Enwezor’s supporters.

“Young men” as “Organizing Secretaries”

From our first days in Onitsha, Helen and I are astonished at the variety of educational and occupational accomplishments we encounter among Onitsha people. Some examples of this diversity have already been described, but here it seems important to emphasize the senses in which, at a very early stage, we come to feel at home. People of widely differing backgrounds and orientations offer us welcomes, some of which are very much recognizable to our own culture, some rather disconcertingly so. We do not fully appreciate the historical contexts of these feelings of cultural deja vu until a number of years afterward, for example when I (much later) began reading the colonial era words of Zik from his West African Pilot. Consider this passage from 1942:16

INSIDE STUFF by “ZIK”*

The Neglected Ibo

I am sure that the non Ibo element among my readers will be broadminded enough to allow me to use this column, today, to defend the escutcheon of the much neglected Ibo, particularly in the realm of Nigerian politics.

Whatever I may write is not to be deemed either offensive against any other tribe or at the expense of any other person.

Indeed, an objective approach to the study of the status of the Ibo speaking peoples in the social evolution of Nigeria is now necessary, if the governance of this country must attain to its ideal and make life worthwhile for the greatest good of the greatest number.

It is most unfortunate that… in most official publications, State Papers, gubernatorial addresses, and statements of public officers, the Ibo tribe was virtually misrepresented, due to an amazing ignorance of the origins, nature, and functions of Ibo ethnography. Pseudo scientific statements were published to the effect that the Ibo people were “primitive” in their societal organization, that they had no political capacity, and that they were “backward” compared with other “enlightened” and “advanced” Nigerian tribes.

With the passing of the years, the spirit of the Ibo began to assert itself, the soul of the Ibo began to rebel against this species of man’s inhumanity to man, and it became clear that the Ibo is a dynamic tribe that has its share to play in the future destiny of Africa….

Thanks to many sources, the mist of ignorance is fastly disappearing before the rays of the sun of knowledge…. To have an unbiased and objective view of the people, it is wise that the seeker after the truth should consult the following publications, among others:

1. R.C. Maugham, “Native Races of Africa” a series of articles in the “West African Review” where he postulates the thesis that the Ibo was among the most mentally vigorous and physically dynamic tribes on the whole African continent.

2. Dr. C.K. Meek in his “Law and Authority in a Nigerian Tribe” submits the view that the Ibo peoples are exceptionally adaptable and were “one of the largest and most progressive tribes in Africa”.

In Chapter XIV of his book, this anthropologist adduces evidence to show that… the Ibo… are essentially democratic in their political system.

Said he: “It is incumbent, therefore, on the Government to recognize and utilize fully this basic institution and to avoid the mistake of regarding any Ibo community as a mere collection of individuals.”

Set aside for the moment the problem of Zik’s identification, as an Onitsha man, with the “Ibo man”: here he is clearly acting as a spokesman for a newly-recognizable ethnic group. Note rather how he emphasizes an “objective, social science” point of view in this article. This major heroic figure from the pre-independence era of African nationalism took an M.Sc. in Anthropology from the University of Pennsylvania in 1933. When he returned to Nigeria in 1937 to forge his nationalist movement using techniques of American “yellow journalism”, he buttressed his combat with Colonialism by the authority of his credentials in social science.

The popularity Zik has attained by 1960 among Igbo speakers (though by no means universal) generated a “halo effect” for “social scientists”, especially American ones, and Helen and I were very much beneficiaries of this aura, entering a community many of whose members already to some extent appreciated the cultural relativism displayed by such “social scientists” and whose members had also long emulated Zik in their striving for (and achievement of) higher-educational degrees.

Note, in addition, Zik’s emphasis on a calculus of “democracy” attributed to the traditional culture of the “Ibo tribe”, an emphasis which stresses not only this socially horizontal value against the verticality of colonial domination, but also points to the community implications of democratic process among this people in their precolonial lives. While one may readily exaggerate this “democratic” dimension of “traditional Igbo culture” especially in light of the pervasive slave trade during the 19th century, it should not be discounted either, since every ethnography of the Igbo in Eastern Nigeria describes its “democratic” forms.

Fundamental to these in the precolonial structures are such institutions as community clusters of roughly equivalent, land holding descent groups, age sets, the masquerade and other associations, and patterns of intra-community intermarriage, which produce a wide variety of “cross cutting alliance” institutions that generate the kinds of social fields Donald Black has called “tangled networks”, where conflict management through “negotiation” is strongly stimulated 17 . The community which calls itself “Onitsha people” (Ndi-Onicha) has a very tangled array of these, and while they also have a complex of vertically-separating instruments of social stratification that are less institutionally developed among their igbo– speaking neighbors, cross cutting alliances are strong enough that one can talk of “democratic processes” here as well. 18

As more or less typical rising-middle-class intellectual “Americans” 19, we tend to reject pretensions of “social class” and like Bill Clinton 30 years later in another context, we tend to seek out the “middling folk” instead of isolating ourselves among “exclusive elites”, and this enhances our “popularity” among many in the Onitsha populace as compared with other (as they often label them) “Europeans”. And this experience, in turn, enhances our own impressions of the “democratic” aspects of Onitsha.

Helen and I decide very early in our fieldwork that we will not seek intensive personal involvements with the Onitsha modernizing affluent elite, a decision rooted both in the understanding that such involvement would considerably distract us from giving the Inland Town Onitsha community the kind of close attention we feel our major research goals require and also in the very pragmatic recognition that our extremely limited financial resources cannot sustain such involvement.

We find relationships more in tune with our aims (and more congenial to our personal tastes as well) among local Western-educated secondary school graduates (working toward higher degrees, mostly by correspondence) who have not yet established themselves in a career, and who both have time available for and are interested in acting as mediaries between ourselves and Onitsha elders. Byron Maduegbuna is the first of these with whom we establish long term working relationships, and Obiekwe Aniweta is the second.

We first met Aniweta through Ikenna Nzimiro, a young Nigerian from Oguta (a well known Riverain Ogbaru or Olu Igbo-speaking town culturally related to Onitsha) who was a son of one of the richest women traders in Eastern Nigeria. Nzimiro became prominent during his youth as a leader of the Zikist Movement, one of the radical nationalist “vanguards” of the late 1940s and early 1950’s whose members supported Nnamdi Azikiwe’s nationalist campaigns against British colonial rule. When British-led African police killed 21 striking Enugu miners in November of 1949, the “Zikists” (regarded as the militant left wing of Nnamdi Azikiwe’s NCNC) responded decisively by instigating acts of civil disobedience in Aba, Port Harcourt, and Onitsha. Nzimiro, then President of the Onitsha branch of the Zikist Movement, led a closure of the Onitsha Main Market in a “Day of Mourning” for the miners, was sentenced by a Colonial court to nine months in prison for this action, and become something of a revolutionary hero during the confrontational politics of that time.

Although widely recognized for his nationalist leadership, he was given no post in the new Independence-era Eastern-Regional Government, so Ikenna pursued his higher education and in the fall of 1960 when we meet him he is doing field research in Eastern Nigeria towards a doctorate in Sociology from the University of Cologne. 20

We discuss our overlapping interests in research and find them mutually compatible, and support each other in a variety of ways. We go together to talk with Onitsha chiefs and elders, and Nzimiro also introduces me to Aniweta, then a teacher in the Roman Catholic secondary school at Oguta but vacationing at his home in Onitsha Inland Town. 21

Obiekwe Aniweta was born and raised in Onitsha, the senior son of an untitled, poor farmer and his Onitsha wife (both of whom had lived most of their lives in Onitsha). His father died while Obiekwe was a child, leaving him in severe financial straits, but the Mother’s People of his father, the Ekwerekwu family, were wealthy Onitsha landlords and helped foster the education of this obviously bright lad. He attended primary school under the CMS and then secondary schools under the Roman Catholic Fathers, where his own intelligence and assertiveness began to conflict with theirs.

Obiekwe Aniweta was born and raised in Onitsha, the senior son of an untitled, poor farmer and his Onitsha wife (both of whom had lived most of their lives in Onitsha). His father died while Obiekwe was a child, leaving him in severe financial straits, but the Mother’s People of his father, the Ekwerekwu family, were wealthy Onitsha landlords and helped foster the education of this obviously bright lad. He attended primary school under the CMS and then secondary schools under the Roman Catholic Fathers, where his own intelligence and assertiveness began to conflict with theirs.

He married an Onitsha woman, and by April of 1961 he is living with her, their two small children, his mother, his junior brother and the latter’s wife, in his father’s modest house in Umu-Anyo village in the Inland Town. Most of his life experience has centered around the Inland Town, though he has recently worked briefly as a secondary school teacher at the National College in Oguta, and he is now (in 1961) employed as Principal of the Premier College, a struggling private commercial secondary school located in the ramshackle “town hall” of the Onitsha Improvement Union. The job gives him only a modest salary but considerable free time, since his primary task involves periodic inspections of the College premises, and his main economic support now depends on occasional secretarial work for Enwezor.

As Helen and I become involved with Nzimiro and Aniweta, we find each to be gentle and undemanding toward us, tolerant of our ignorance and other social limitations. Because from the beginning we mutually define our cooperation as voluntary, each party free to pursue it as schedules and inclinations might permit, power relations do not become overt issues, and a kind of collegiality develops, partly because we are roughly the same age (pushing 30) and at similar stages of the life cycle (university degree-seekers, not yet established in our careers), partly because we all feel marginal to the societal contexts in which we dwell (and interested in exploring the meaning of this marginality), and partly because (though for rather different reasons) we have “time on our hands” for doing some kind of research.

In building our own lives in Onitsha, Helen and I find working with people like Nzimiro and Aniweta especially congenial, partly because they substitute for a university student cohort we have recently abandoned upon departing from Berkeley. Like those students, they share a concern for the socially disadvantaged, as well as specific critical perspectives toward many current features of American and European international policy (for example, U.S. overflights of the Soviet Union, French atomic testing in the Sahara, questionable U.N. and other European-led activities in the Congo), all of which we can discuss. Moreover, we share interests in discovery through social research, and enjoy talking about theoretical issues.

While both men become stimulating colleagues and friends, their ideological commitments are well to the left of ours, and different as well in other ways we do not fully understand. Each is strongly assertive of ideas and ideals, and prepared to act upon them in impulsive, rather uncompromising ways on the local scene. In their interest in social change they adopt Marxian perspectives and are sharply critical of the current Nigerian Establishment’s emphasis on capitalist development and its associated greed for money, invidious status distinctions, and foreign goods and capital.

Helen and I take ideological stands labelled “Parsonian liberal”, referring to the theory of the late eminent American sociologist Talcott Parsons, whose views on contemporary world society remain both relevant and controversial today,though his name has faded from view. In my opinion, Parsons’ social thinking was outstanding in both its comprehensiveness and open‑mindedness, though his perspectives have justly been criticized for encouraging one‑sided glorification of the “modern” and for excessively privileging the “social scientist” point of view.

We often find our new frends’ more radical opinions quite challenging, and admire their strong convictions from our own critical awareness of the inequalities and acquisitiveness of both American and Nigerian capitalism, though we remain unsure of what kinds of alternatives to capitalism might really work to produce more equitable and also relatively free societies. But while we share these common grounds of attitude and interest, from the perspective of a committed democrat I am often baffled by some features of their attitudes toward the exercise of power in society.

On the one hand, each clearly thrives in what seems to us a somewhat liberally open society in many social contexts, and each especially cherishes his ability to express his views freely and to challenge establishment authorities with whom he disagrees. But on the other hand, as strong admirers of both the Soviet Union and Communist China they express a longing for a truly powerful, decisive leader of the country who will lead it in a strongly socialist direction, and they are therefore attracted to the promise of Chike Obi, the Onitsha man who has taught mathematics at the University College, Ibadan, and whose new “Dynamic Party” promises a style of decisive Nigerian leadership said to be modeled on that of Kamal Ataturk.

Believing that Zik has “sold out” to the “opportunistic commercialists” now leading the NCNC, both Aniweta and Nzimiro agree that a totally new leadership, which will make decisive changes by demolishing the current regime of vested interests, is essential if a genuinely independent and socially responsible Nigerian nation is going to evolve.

They envision a totalitarian organization of power, a leadership both able and willing to strike down all opposition with an iron fist, and they embrace these opinions not secretly but openly and assertively. To me, these different points of view seem mutually contradictory: they too readily assume they will each be associated with the sources of such power, failing to consider the far more likely probability that they will become objects of its use (while they take for granted the existence of an open society whose future existence should be viewed as very problematic).

We experience this constellation of attitudes widely among young higher- education- oriented men we encounter in Onitsha. Interviewing some of the (generally less well educated) Igbo men living in the Waterside, I occasionally meet what seem very extreme forms of colonial rejection, for example while visiting some junior clerk or elementary school teacher during my census work there, I see prominently displayed atop his dresser a framed photograph of Adolph Hitler. When (trying to contain my own then-automatic feelings of hatred and horror at the sight of that brush-mustached Gestalt) I inquire why my host gives Hitler so prominent a place in his private living quarters, he responds that he admired first the way Hitler so strongly opposed the British, and second how he would “stop at nothing” to have his way. These interviewees seem quite unfamiliar with Hitler’s attitudes toward people of African descent or his enthusiasm for genocide, but focus instead on admiring the kind of single-minded will to power which could cast aside both caution and constraining normative rules in order to oppose established powers in order to gain one’s ends. Many of the socially-striving people we meet seem to be in some sense attracted to this kind of power image22.

Even Byron Maduegbuna, in many ways much more politically conservative than either Nzimiro or Aniweta (in his strong attachment to the authority roles of the Inland Town, and in his current position of responsibility as Secretary of the NCNC Branch for Waterside Ward C) surprises us with his enthusiastic verbal support of Chike Obi’s proposed tyrannical socialism. Byron bases this stance on his doubts regarding the current Nigerian experiments with Parliamentary Democracy, whose ideals have interested him but to which neither Nzimiro nor Aniweta is much attached. The three men however share an abiding interest in exploring the question of how diverse forms of society “work”. They are genuinely intellectual, critical of the emerging national establishment and interested in theoretical alternatives, and from this point of view their attraction to Chike Obi as representing an untried alternative makes sense for all three.

The Onitsha Inland Town in 1960-1962 contains an unusually large number of “young men” (some of them well over 40; the label referred more to one’s position on a career trajectory than to actual age). 23 These men profess intellectual interests, concerned mainly with formalizing and criticizing the ideologies of organizations (both “traditional” and “modern”).

Of the older men of this set, Jerry Orakwue, the local historian from Umu-Dei discussed elsewhere24, stands in some senses as an equivalent (for Oke BuNabo) to Obiekwe Aniweta (for Umu-Anyo) and Byron Maduegbuna (for Isiokwe), but he is of an older generation, less well educated, and much less strongly concerned with ideology than they. He works as a local agent of the West African Pilot, but his pay in this capacity is insufficient to cover the needs of his now-substantial family and he finds it necessary to supplement his income in various ways. The author of Onitsha System of Title taking, a cultural treatise grudgingly well respected by local people for its meticulous striving for accuracy and valuable details, he also possesses a long if uncompleted manuscript on Onitsha history and various documents of interest to me in my research. He has acted as secretary for various organizations, including some years Secretary for the Home Branch of the Onitsha Improvement Union, he retains the OIU’s minute books in his personal possession, and I eventually negotiate permission to read them (which he granted for a fee)25 Though he has to subordinate his special skills as a scribe and “cultural expert” to the continuous constraints of making a living, he is both a serious student of Onitsha history and an active and rather sophisticated participant in its political life. My estimate is that he earns less respect than he deserves, but other Ndi-Onicha are well attuned to his opportunistic pragmatism.

There are many others, though most are less accomplished in literary pursuits and degree-earning than Byron or Nzimiro or Aniweta. John Ochei of the Umu-EzeAroli Peace Committee, for example, plays a similar role as a “cultural expert” in relation to the Onya, and takes the most strikingly legalistic stance toward Onitsha traditions of anyone I interview (having received most of his education not through any formal channels but by spending endless days observing Onitsha courtroom proceedings), and he views his expertise in Onitsha tradition unambiguously as a tool for advancing the interests of his particular social groups. As we encounter numerous men from young to middle age who play roles as “organizing secretaries” in various kinds of organizations from descent groups to political parties and who participate in social networks that crosscut ranges of significant groups, the importance of such men becomes evident.

To the extent that we gravitate to people like Nzimiro, Aniweta, Byron Maduegbuna, and Jerry Orakwue, and become somewhat distanced from the affluent elite of Onitsha, Helen and I also become more separated from association with the more typical European roles of attachment to facets of the Colonial Establishment. As companions of these familiar individuals, our efforts in the Inland Town becomes more legitimized (at least to the majority of people who are critical of colonialism and hopeful for Nigerian Independence). Our association with such people helps us gain some degree of access to the groups with which they are involved. In the contemporary social context, most organizations need some members possessing literary skills who can translate local-group interests into Westernized frameworks, and in the Inland Town these organizing secretaries fulfill such needs. Highly diverse in personal background, interests, and points of view, each occupies a position working to translate, transmit, and to some degree to transform local cultural knowledge and skills.

7. Gaining perspectives from Enwezor’s home base

I enter the domain of Enwezor’s group primarily through Obiekwe Aniweta, first talking mostly about divisions and authority structures within his own village Umu-Anyo, and about land tenure and various common funds held by Anyo and its sub groups. As the rightful senior lineage priest of one major Anyo subdivision (Umu-Aguzani), Aniweta is remarkably well informed about lineage and village affairs, and knows the whole of the Inland Town very well. Like Byron does for Isiokwe, he supplies me with valuable records of land tenure conflicts involving Umu-Anyo as well as other groups.

During late April of 1961, as I begin working increasingly often with Aniweta on a census of his village, this also affords me an opportunity to become better acquainted with some of Enwezor’s closest supporters and to talk with them about the progress of their race for the kingship. In our visits around Umu-Anyo Village, we often encounter Akunne Enwezor, the junior brother of the candidate and one of his most ardent supporters in the kingship contest. An exuberant, fiercely smiling man in his fifties who takes great pleasure in his Ozo title (he danced with obvious vigor and presence at Emejulu’s title taking), he speaks confidently and matter of factly about their achievements so far and their plans for the crowning of his brother. He provides some additional details, for example, about Enwezor’s ritual of Ima-Nzu; while Adazie Chukwudebe (the most senior priest of all Children of King Aroli) actually rubbed the clay on Enwezor,

“it was not his right to do it. The right belongs to Otumili Agunyego of Oreze family. Oreze family is the most senior son of all Children of King Chima. But as he (Otimili Agunyego) is not titled, he delegated the right on Adazie. But he was there at the ceremony, and now he cannot do it for anyone else.”

This is not the first time I have heard the name “Oreze Otimili,” for this numerically tiny royal lineage has a social significance which at this point is quite vague in my mind. Akunne Enwezor clearly emphasizes, however, that this young man, by virtue of his attendance and proxy participation at the Painting, has committed himself irrevocably to Enwezor’s cause, and that this commitment is likely to have decisive significance of some kind.

Hearing Akunne Enwezor discussing his people’s views, it becomes evident that one basic assumption of the Enwezor group is that Umu-EzeAroli are the sole legitimate king-making group in Onitsha. He regards the people of Oke-BuNabo as the main conspiratory obstacle in his brother’s path, and loses no opportunity to disparage their genealogies. “Many of them are foreigners,” he says bluntly. He also emphasizes that Enwezor’s group intends to move quickly and directly to complete the contest in a decisive manner:

“We are looking for the Ofo of King Anazonwu. If we can get it, it will go to Onowu. Then we will organize (Going to Udo) around the end of this month.”

It also becomes clear that he regards the Onitsha chiefs as the most essential supporters of his brother’s candidacy. In his view the only really important requirement for success besides holding the King’s Ofo and doing the necessary rituals is to win over the chiefs, pivotally the Prime Minister. “If the Onowu omes around to Enwezor,” he assured me, “the rest of the chiefs will follow and that will be the end of it.”

Aniweta agrees that the Prime Minister’s support is crucial, but worries that the Onowu will probably be unwilling to commit himself to Enwezor for some time. It is to the Prime Minister’s advantage to prolong the contest, he says, because so long as there was no king many royal prerogatives will remain in his hands, and while other candidates are seeking encouragement, money is likely to enter his hands. Still, Aniweta maintains that although many of the chiefs are now uncommitted, when it comes to a contest of bidding Enwezor will be able to outbid any of the candidates standing so far.

The Problem of the Owelle

For example, he says, there is the problem of the Owelle, the Sixth Minister, who is currently attending and participating in the Royal Clan meetings. One day Aniweta accompanies me to talk with the Owelle about his village history, and as we later depart Obiekwe pointedly observes that the chief’s concrete-block house (which had been under construction for many months) remains unfinished. “Since he has just completed taking his (chieftaincy) title,” he remarks, “he has no money.” Aniweta suggests that Enwezor could assist in this difficulty.

The Problem of the Onowu‘s wife, Anene

Aniweta claims to be much more concerned, however, about a less widely recognized problem concerning the relationship between Enwezor and the Onowu: the Prime Minister’s wife, Anene, is a Daughter of Umu-Anyo (and a member of Aniweta’s own Aguzani family) but is now spiritually quite alienated from the members of that village.

Some time past she left her previous husband (an Odoje man) and went to live with Onowu, being pregnant at the time with Onowu‘s child. When this child was born, since the bridewealth part of the marriage had never been refunded to the husband, her father insisted that, according to custom, the child should return to the Odoje man. But she adamantly resisted this move, and being a very strong willed woman she irately dragged an Oath around Aguzani sub village of Umu-Anyo.

When soon afterwards her father died, Aguzani family had no alternative but to inflict Ostracism (Nsupu) upon her. She is therefore very angry with the people of Anyo, and , being a woman of strong will and powerful personality (she is said to possess some community-wide powers by virtue of her reputation for prophetic dreaming). 26, she has very strong influence over the Onowu. This is now working against Enwezor’s cause due to her resentment at her Ostracism by the Umu-Anyo.

Aniweta (who is in fact the woman’s senior lineage priest as the rightful head of Aguzani family) expresses fear she might even be able to defeat their cause. “We are negotiating with them,” he says.

The Problem of the Eastern Region Ministers

Early in May Aniweta tells me that he has just gone with Enwezor to Enugu, to visit several Eastern Region Government Ministers there. The Ministers tell them that they support Enwezor, he said, and promise to recognize him as soon as the Onitsha Prime Minister might bestow his approval. Summarizing his sense of the NCNC- dominated government’s view, Aniweta said, “The government supports Enwezor because he has always given the NCNC much money two hundred, three hundred pounds (Sterling) at a time. So he is using his power gained as a long time supporter of the NCNC”.

As I become better acquainted with Enwezor’s people, their organization begins to appear to me to have as its core the combination of a solid phalanx of his lineage members (Umu-Anyo) plus the pivotal members of the Umu-EzeAroli Peace Committee discussed earlier (excluding of course Moses Odita) and one non- royal senior chief, the Odu (who wields very considerable influence throughout the town).

They appear to see their broadest task as one of drawing particularly significant individuals and groups into acts that would formally commit them to Enwezor’s cause, and to regard as their most salient opposition that major section of the Royal Clan which has “stolen” the kingship from them in 1900, namely the members of Oke-BuNabo (whom they tend to stigmatize as “foreigners”).27

Their strategy is to aim toward winning the commitment of a majority of the chiefs (focally the Prime Minister) and then with that support to win the recognition of pivotal officials in the regional Government, and they see their main problems as finding the routes where effective symbols of influence can be mobilized toward those aims.

Hoping to gain better understanding of their views, I enlist Aniweta to request that the members of the Umu-EzeAroli Peace Committee provide me with their minute books, making the same offer of reciprocity I have done with Byron, that we will provide them with a typing service to render more legible copies of the material. When Obiekwe did this, but they declined.

I continue to work with Aniweta throughout our stay in Onitsha, finding him even more than Byron a congenial collegue. He has capacities to relax and enjoy himself, adopts unpredictably ironic views toward social life that are pleasing to us. It is also clear that unlike Byron he assigns relatively little value to his own local and traditional knowledge and social position. When he escorts me to witness Umu-Anyo rituals, he will often sit at a distance reading one of the national newspapers while the ritual proceeds.

In practical affairs, he takes an active interest in Inland Town politics, is an Executive Member of the Umu-EzeAroli Youth League, Assistant Secretary of the NCNC Inland Town Branch, and also Publicity Secretary of the Onitsha Youth League. He regards these positions as ways of keeping his fingers in touch with Onitsha politics with the intention of eventually vaulting himself into more important roles in these organizations in order to “radicalize” them. He hopes, as he puts it, to bring the methods and organization of the world Communist movement to bear upon local affairs.

For the time being he plans to work for Enwezor as his secretary and assistant, with the anticipation that Igwe Enwezor may assist in his further education at the University of Nigeria at Nsukka or (failing that) to obtain a scholarship for Friendship University in Moscow. Toward that more distant aim, he has become Secretary of the “Nigerian Soviet Friendship Society” and has posted a sign proclaiming his office in the center of Umu-Anyo village along Bishop Onyeabo Street, directly across from the Enwezor family compound.

The pathway to Aniweta’s own house leads just to the right of the pink-colored building, which is the shrine dedicated to Ezu-Mezu, a spirit fostering childbirth and protective of small children, in this case for all Umu-Anyo. Newly-reconstructed through the efforts of candidate Enwezor, this highly visible icon of his numerous efforts on behalf of his immediate descent group faces directly onto Bishop Onyeabo Street alongside the tree dedicated to Ani-Umuanyo. 28 Note in the image here that two young women are standing in the shade of this shrine; they have presumably been directed there to by the elders to absorb some of its fertility powers.

An avid reader and writer working towards a B.Sc. in Economics through correspondence courses, he has bookshelves containing works by economic historians and social scientists devoted to the cause of British Labour, and his interests in ideas are consistently and openly practical: he self consciously seeks to apply his expanding social science knowledge to the immediate tactics of action in his own social scene. His search for practical methods of gaining power has led him to his current reading of the works of Lenin and of Josef Goebbels, and the passages underlined in these books emphasize the deploying of utterly pragmatic tactics in the political process (those most efficient for “winning the game”, with no limits being set on levels of contentiousness).29 To the extent that he is oriented to the interregnum process, Aniweta’s aim is to bring more systematically efficient pragmatics into the scene, and toward that end the ideas of Josef Goebbels seem as potentially useful as those of any other interpreter of political conflict processes.

9. Local intellectuals vary widely

There are probably at least as many kinds of cultural entrepreneur in Onitsha as there are individuals of marginal means who are interested in intellectual issues. One unemployed man I work with briefly in 1961 introduces me to The Tibetan Book of the Dead (of which I have not previously heard), while another, older person who claims to be a Native Doctor (dibia) displays over one of his doors a diploma awarded to him in 1933 by an equally unfamiliar literary source, one “L.W. de Lawrence, High Caste Adept in Art Magic and Famous Magician by Alchymy and Fire”, of Chicago, Illinois. Someone living in the compound of Akunwafor Erokwu along Awka road advertises himself as a “Genuine Red Indian Witch Doctor”. People express considerable interest in Rosicrucianism as well as Freemasonry, not to mention a wide variety of other formal ideologies. A detailed list of evident philosophical interests current among Ndi-Onicha would soon become endless.

Some of the more “spiritualist” of these ideologies were introduced to Onitsha people by John Stuart-Young, the English trader-poet-mystic who lived in the Waterside compound of an Umu-Dei family during the first third of this century. In 1911 he included a member of this family, Hayford Bosah, on his vacation in England, and upon their return Bosah became both an enthusiastic advocate of English ways and a local instructor of such occult English arts as “divination, levitation, and the cabala”. 30.

While to some extent I encounter similar patterns among the Ndi-Igbo living in Onitsha Waterside, their interests operate for the most part on a different level. Ndi Igbo are the main writers as well as readers of the now famous “Onitsha Chapbooks”, which aim largely at males with primary-level educations. Brief, clearly written, and cheaply produced, these pamphlets focus mainly on the strivings of mobile individuals alternating experience between the new values and demands of commercial urban settings and the constraints of their traditional pasts. Many preach a moral code similar to the “Protestant Ethic”: self denial, self discipline, frugal saving and investment of privately won commercial gains, avoiding the dangers of self-indulgence in drinking places or in the arms of the opposite sex.

Many of these pamphlets are explicitly designed as guides to the best roads to success hard work, bold assertiveness, scrupulous honesty, persistent attention to necessary details. While they focus on gaining material wealth, prestige items of Western manufacture, money and credit standing, they are also largely pervaded by Christian idealism: the moral and responsible person, however lowly in social status, will ultimately be rewarded, the corrupt will eventually suffer their just deserts. Everywhere, the individual is held responsible for his or her fate. In contrast, they reject tradition wherever it contradicts the requirements of modern life: a prime villain in the novels and plays is the pidgin-speaking, village dwelling “chief”, often depicted as drunk, greedy, deeply anti Christian, demanding an outrageous bridewealth for his daughter or using his ill gotten money to claim for his wife an educated young girl whom an urban dwelling young man hopes to marry. Insofar, then, as they reflect a “character type”, it is a walking advertisement for Westernizing modernization: the individualistic capitalist entrepreneur building a successful life through honest, systematic productive endeavor. 31 Nwoga 1965 provided a brilliant orienting discussion of this literature. Obiechina 1973 gives an excellent summary of the significance of these chapbooks, which have been much analysed and interpreted.)).

I never see any Onye-Onicha reading one of these chapbooks. Most Ndi Onicha young men I encounter have moved beyond this strongly Christian idealism, with its intolerance of their people’s own traditional past (a position which however had characterized the Inland Town more strongly during the years prior to the nationalist era), and are exploring wider ranges of cultural options. In some measure this is a function of their distinctive ecological position in the historical development of the Nigerian scene. As one writer of the 1950s put it, “the list of famous sons of Onitsha (Inland Town) is staggering when one considers its small size”32. The achievements of Ndi-Onicha during the past 100 years have made them the objects of great admiration and envy by the later Ndi-Igbo immigrants, and young Onitsha people are aware of this reputation when gauging their own career options.

When both Anglican and Roman Catholic Christian missions established their educational centers in Onitsha Waterside during the second half of the nineteenth century, Ndi-Onicha were the first to take advantage of the opportunities thus provided. Since they were always labelled by Europeans and other non Igbo speakers as “Ibos”, they subsequently became the pathfinders in “Ibo” attainment of many esteemed Western professional positions: the “first Ibo” Pastor (the Rev. G.N. Anyaegbunam), the “first Ibo” members of the Nigerian Legislative Council (I.O. Mba and S.C. Obianwu), the “first Ibo” Anglican Bishop (Archdeacon A.C. Onyeabo), the “first Ibo” lawyer, then High Court Judge, then Chief Justice of Eastern Nigeria (Sir Louis Mbanefo), the “first Ibo” Roman Catholic Sisters (Maria Anyaogu and Clara Oranu), the “first Ibo” doctor to establish private practice in Eastern Nigeria (Dr. Lawrence Uwechia), the “first Ibo” Catholic priest, then Bishop (Fr. John Anyogu), the “first Ibo” to attain international political fame (Nnamdi Azikiwe), the first Speaker of the Eastern Region House of Assembly (Ernest Egbuna), the “first Ibo” matron at the first hospital established in Igboland (Grace Ifeka), the “first Ibo” Auditor General of Eastern Nigeria (Fred Umunna), and many other pioneering distinctions in fields ranging from mission education, government service, and medicine to commercial and industrial fields of endeavor including training institutes, printing presses, transportation and industrial mechanics, road and building design and construction, trade union activism, agricultural sciences, law, art, journalism, literataure, the social sciences, mathematics, and metaphysics, all of these were pioneere by Ndi-Onicha.

But these many-sided triumphs of accomplishment did not lead in the long run to destruction of traditional culture Onitsha, because from the earliest colonial encounters two processes worked to sustain the basics of that ancient tradition: the increasing monetary value of Onitsha urban lands (which remained largely in the hands of the Ndi-Onicha descent groups and their tradition supporting elders) and the chronic tendency of those obtaining wealth through Western avenues to invest in achieving traditional titles. A “neo-traditional” elite, armed with some of the educational skills and advantages provided through colonial channels but also committed to sustaining major aspects of the old regime, continually reproduced itself even as the spread of Christian ethics progressed33.

Another side of this astonishing florescence was a diaspora of Onitsha sons and daughters, first into other parts of Nigeria by the turn of the century, then gradually becoming an influential stratum of urban centers throughout Nigeria and spilling further into other parts of the world. While I have seen no systematic census of Ndi-Onicha living “abroad” (outside Onitsha), today they probably outnumber the local indigenous residents by several fold (the proportion of expatriates having probably increased progressively during recent times except at the height of the Biafra War and its immediate aftermath). From the earliest period those living abroad both sent very substantial remittances home and extended hands of support to their home relatives enabling them to explore opportunities elsewhere, whether these involved new educational opportunities or new job openings.