[Note: Click on any image you may want to enlarge.]

Helen and I had just arrived in Nigeria in late September of 1960. We stayed in Lagos very briefly where we got our necessary papers, bought a small car (the first of our many mistakes: we look at a used VW bug but instead bought a new Fiat 600 for a somewhat cheaper price), then spent a few days in the “Ford Flats” at the University of Ibadan where we meet various fellow academic visitors. This in itself was quite a culture shock: British customs are significantly different from American ones; for example,I quickly became a convert to the English styles of eating at table, finding two-handed wielding of knife and fork definitely superior to the American “upper-class” custom of mainly using one at a time. (I had always found this an inefficient cultural custom.) Soon however we are driving our new vehicle from Ibadan in Western Nigeria to Onitsha in the East. This was an adventure too full of culture-shocks to recall here (none of them problematic).

After a brief search for housing, we moved into our upstairs rental flat on the southern edge of Onitsha Inland Town (enu-onicha). When October First 1960 arrived, still settling in, we had this delightful moment below, seeing schoolchildren from Metropolitan Grammar School passing down Ugwunaobamkpa Road on their way to join the Independence Day celebrations. They saw us standing out on our balcony, and stopped for a while, chanting in unison at us in celebration (presuming, I suppose, that we were British citizens whose 60-year reign over the town is now ending, so their chanting was probably jeering in tone). We cheered too, and waved back at them, regarding ourselves as part of the New Order, not of the old (we Americans know well the meaning of “Independence”, after all).

We then drove to Onitsha Sports Stadium where the Independence Celebration was to be held. Since we had met no acquaintances who could escort us, we were on our own and joined the crowd as it entered.

Here a memory inserts itself that I have tried for years to erase from consciousness: we were accosted at the entry by a rather elderly man who was what we would in the U.S.A. call “a cripple”: he had lost the use of his legs, but managed to propel himself about using various canes, dragging his legs along with him. I no longer recall the details of this, but he was very shabbily dressed, and he attached himself to us vigorously like a leech, saying that we were “imperialists” who had forced him to fight during World War II, and we therefore owed him money.

I tried to explain that we were not who he thought we were, but he would not listen. As we walked along the periphery of the field looking for places to sit, he went along with us stride by stride. When we found a space to sit, he sat down close beside us.

Of course, we had no familiar escorts,at this time, or they would have dispersed this man. The crowds around us seemed oblivious to our presence. So I asked him what we owed him. He said 5 pounds sterling. This was a lot of money to us: we had just agreed on a rental rate of 12 pounds per month, which seemed about the maximum we could afford. But grasping that otherwise we would have this “companion” beside us throughout the afternoon until we returned to our car (and to be honest feeling a revulsion to his presence), I paid him the fee and he promptly departed. (This memory still disturbs me; it brings back that feeling, which I don’t recall having before, of being physically attached to a human leech.) I also remember that this was not a trivial loss for us at the time — we were not “rich expatriates”, but making-do graduate students with quite limited funding.

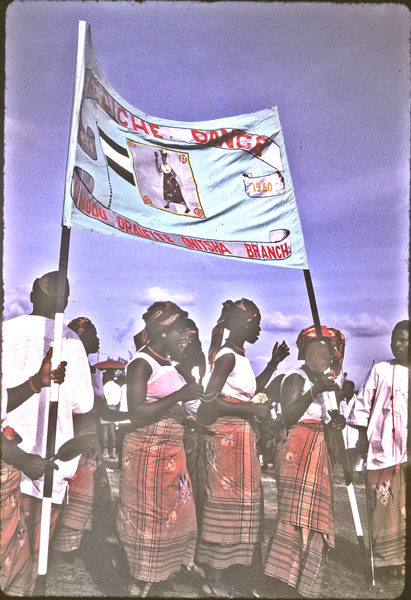

It’s appropriate now to note , anticipating the photographs that will follow, that I had great difficulty learning to use my new (Aires) camera in the African tropical sun, and indeed never really mastered my photographic tasks with this piece of necessary equipment. We would mail our exposed film to England for processing, so had to wait weeks to see the results of our work. All of the photos I took at the stadium were grossly under-exposed — as you may notice, and so I have had to Photoshop all of them drastically in order to provide the rather poor images you will see here everywhere in this volume.) We also knew almost nobody in town at this point, so we blundered into the stadium after some of the dancing groups had already arrived and performed. The first images in the sequence order I record are these of an Oraifite Town women’s dancing group (sponsored by the Onitsha Branch of Oraifite Improvement Union):

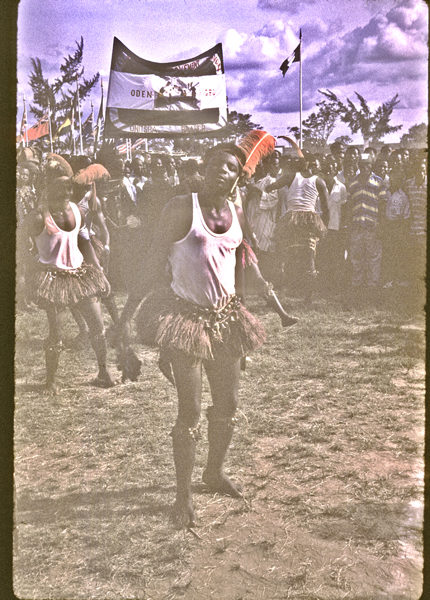

Another group I photograph is this collective of young men dancers, representing the Onitsha branch of another Ndi-Igbo town’s Improvement Union.

Having grown up mostly in the small-town American west (Casper, Wyoming), I had personally known very few black people (interacting courteously, but at a distance), but after this close-up experience in the Onitsha Sports Stadium, any unconscious stereotypes I might have carried from childhood regarding the appearance of people of African descent are utterly demolished. Standing in this massive crowd of thousands is a life-transforming revelation for me, one I have carried with me all of my subsequent life. (I remember thinking, “Every one of them is absolutely unique!” — any “black” stereotypic-image I might have had vanished forever.)

The main portion of the celebration that we witness is however relatively brief. The Obi of Onitsha arrives in a limousine, stands on a high platform, and speaks briefly to the crowd over loudspeakers. Then other officials join him and also give very brief remarks. Knowing little of the Igbo language, we understand nothing being said.

I venture out onto the field at one point, following the lead of some other photographers. Along the east flank of the stadium a long shading arbor has been set up which accommodates various parties allocated elite social standing. I do not venture to walk along the line on this day. (The white-robed figures standing at far right are leaders of a local church.)

Then commences the parading of a large array of local schoolgirls, all in uniform, marching past the reviewing stand.

Ranks of Onitsha schoolboys follow, striding in a much more formal, militant way.

A group of women dance. I fail to identify them, and this photo is probably out of sequence. (Several of the set may be). Things happen so fast the first few days we are in Onitsha that many events are poorly registered.

A contingent of local Muslim representatives appear at one point. (They typically join local celebrations as a compact, unified group, and pursue their own schedules, disregarding the more formal ones generated by external authorities.)

I manage to capture a glimpse of a particularly striking woman along with two red-capped chiefs, as the crowd begins to disperse at the end of the ritual process.

For a detailed visual tour of Onitsha as it appears to us during our stay there from 1960 to 1962, go to Chapter Two of this volume, “The ‘New Nigeria’ 1960-62” and travel about the city. Most of the images you will see are considerably better in quality than these sorry efforts just presented above, and more are available in all of the pages and chapters of A Mighty Tree website than most readers will ever have the patience to consult.

Viewing this page (above) once more from the memory perspective of many decades, I realize that my experience (outlined above) with the disabled, angry Nigerian veteran at the event was significant in light of what later happened. I might have added that, when I entered Nigeria, I had previously suffered some serious emotional set-backs, “Beat-downs”, one might call them. At the time, my personal psychology had become so weakened that I was unable to deal effectively with the challenges brought by overtly aggressive persons of the kind described. earlier on this page. two years in Nigeria wrought in me some very substantial changes: by the time I left Nigeria, I was fully able and willing to respond to this kind of aggression in equally assertive terms. Onitsha people, in a wide variety of ways, taught me that lesson so well that my life has taken very different courses ever since.

At Home After the Celebrations October First, 1960

Here I have decided to indulge myself and tell about our late evening after these pictures were taken. First I must say something about the upstairs flat we rent at 24 Mba Road. This building is owned by Albert (Ozomma) Erokwu, where he lives downstairs with his wife Merci and their three children. We have been in the upstairs flat only two or three days, but by now we know that the “running water” provided in it actually runs only very occasionally (and it seems, unpredictably. Apparently a tree has fallen over the water pipe somewhere in the Inland Town, partially but not entirely disabling the pipe, so that water only runs from time to time depending on amounts being used elsewhere. We have already learned to leave the bathtub turned on with the drain-plug in place so we will catch water whenever it decided to run.

Where we go after the public celebrations I have completely forgotten, but when we returned to our flat the evening after the Celebration photographed above, we climb up our stairway to hear a roar emerging from our rooms. We don’t ask what that sound is, since at our front door we can see inside substantial water filling the entire floor, every room now several inches deep and filling! Horrified, we seize a broom and begin trying to remove the water through the front and back doors. Our shouts arouse the three Erokwu children downstairs, who come up and immediately begin helping us deal with the problem. One of them thinks to grab empty drawers from a chest and use these to scoop up water. Together we eventually get the job done (and the floors nicely cleaned, by the way) and I creep downstairs to survey the anticipated damage in the flat below. The Erokwu children’s grandmother is present, and to our great relief she appears entirely unaware there has been any problem. I see a couple of tiny damp spots in the corner ceiling of the downstairs living room, but that is all. This, I realize, is one well-constructed cement-block house (see a view of it here below). All while we were scooping out the water I was anticipating imminent floor collapse. Now at least we know are occupying a sturdy house. (We also recognize our folly in leaving the faucet open: most other residents of the Inland Town no doubt attended the many festivities occurring in the Waterside, so water use in the Inland Town had plummeted, and hence our bathtub received a continual supply in full force.)

We trhow most of the water out the front door, located behind and slightly left of where Helen is standing in the photo.

A day or so thereafter, a relative of Ozomma Erokwu escorts us to the office of the Onitsha Water Works, still occupied by an Expatriate official who, perhaps taking note of the obviously distressed “European”-looking couple standing before him, sees to it that the offending tree trunk is promptly removed, and we never have water problems in the building afterward.

This building survived the Biafra Civil War of 1967-70, though the hipped roof was blown off during that time (replaced by a slanting one, as we saw during our subsequent visit to Onitsha in 1992).