1. Formal Announcements

[Note: Click on any image you may want to enlarge.]

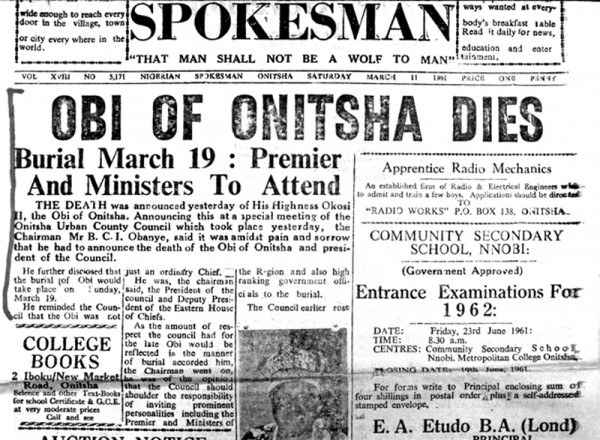

By March 10, 1961, Obi Okosi II’s immediate descent group, the Umu-Chimukwu (“Children of Chimukwu”), has completed its series of ritual announcements made to Ndi-Onicha Indigenes (and selected others) of the king’s illness and its culmination. On Saturday, March 11, the Nigerian Spokesman publicly proclaims:

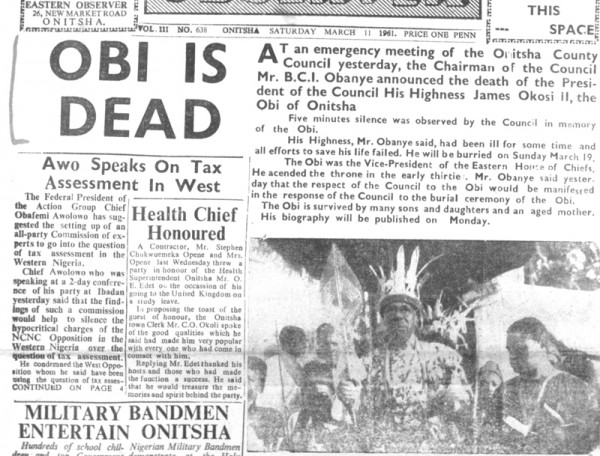

and thus the period of fictional vitality comes to an end. Under this headline the Chairman of the Onitsha Urban County Council (OUCC), B.C.I. Obanye (an Onye-Onicha and member of the Mgbelekeke family — this latter a major ritual participant in the Inland Town and even more major major landowning group in the commercial “Waterside” or Otu) — states that the OUCC will “shoulder the responsibility of inviting prominent personalities including the Premier and Ministers of the Region and also high ranking government officials” to the funeral, now scheduled for March 19. The Eastern Observer prints a similar article, with a slightly different tense-implication:

Note that both sheets emphasize the point attributed to Mr. Obanye “that the respect of the Council to the Obi would be manifested in the response of the Council….”

On subsequent days both newspapers are filled with the subject of Okosi II, including obituaries, messages of condolence, and lyrical eulogies. On the 13th, the Spokesman editorializes that

“Obi Okosi was a King with more than a nationalist blood. In Nigeria he found a leader of the African race, and in Africa, he saw a towering force in the solution of international problems. He believed in ‘charity begins at home,’ and towards the achievement of internal unity, peace and security he dedicated himself…. And so, in Onitsha, King Okosi II worked ceaselessly silently towards solidarity and mutual understanding and respect among all tribes within his domain. In and out of the Palace, his aim was to weld all diverse opinions together with a view to carrying a crusade of peace and unity outside his territorial boundaries in this country and, eventually — all Nigeria thus blended in common understanding — to carry all Africa with her into the front of all the world powers.”

“Obi Okosi II, among all his predecessors, lived to see a united Onitsha, an Onitsha where all tribes not only fraternized but lived as of one parent, regarding the problems and difficulties of one as those of the other. He was a loving and lovable ruler. Height — enchanting. Voice — commanding. Life — exemplary.”

These words give Kingship a significance as might be envisioned by a functionalist anthropology, viewing it however in an expansionist mode as part of a goal aimed toward the unification of all Africa, with the late Obi playing his part in leading a “crusade” of expanding love relationships in this corner of the continent. In emphasizing the King’s role relating to Nigeria and Africa, one may detect an oblique reference to Zik’s (and the NCNC’s) political leadership (Obi Okosi II was a patrilineal lineage-mate of Zik). However, even in its reference to a “united Onitsha” as an historical reality, the Spokesman is stating hegemonic doctrine rather than fact, since the current OUCC comprises a carefully if precariously balanced structure of oppositions between those supporting the Ndi-Onicha and those supporting the immigrant Ndi-Igbo from the immediate eastern and southeastern hinterlands, and “Ndi-igbo” is a pejorative name for many Ndi-Onicha. In very recent times, indeed since our own arrival in Onitsha in September of 1960, one facet of these oppositions has become violent.1

On Thursday, the 16th, the Spokesman publishes a telegram sent by His Excellency the Governor-General of Nigeria, Dr. Nnamdi Azikiwe, addressed to Chief Anatogu Onowu (the Prime Minister of traditional Onitsha Inland Town) and to the OUCC:

“The announcement of the death of our father Obi Okosi is tragic. We mourn with the chiefs and people of Onitsha in their hour of sorrow. We cherish his memory and pray that his soul may rest in peace.”

The subsequent issue of the paper quotes several “messages of sincere condolences” from the Commissioners of Onitsha and Owerri Provinces and, in particular, from the Honourable P.N. Okeke, member for Onitsha Province in the Eastern House of Assembly and the current Minister of Agriculture for Eastern Nigeria. Okeke, a prominent Igbo man who has previously acted as a leader in the “Non-Onitsha Ibos Association” during their recent political battles with the Onitsha indigenes over control of the OUCC, now mourns “the passing of our revered king and president”, and prays that “God grant wisdom and light to kingmakers to find a worthy successor.”

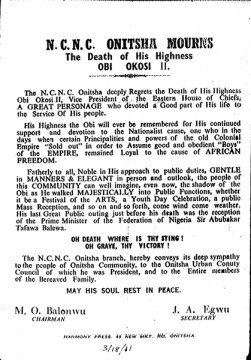

On Saturday March 18, most of the Spokesman is devoted to the subject of the king’s death and imminent burial. A front page statement is presented by the NCNC:

Moses Balonwu is a very prominent Onitsha Indigene.These and several other messages from N.C.N.C. representatives emphasize the Obi‘s official position in relation to Municipal, Regional, and National Governments (stressing both his consistent support for Zik during the latter’s struggle to wrest political power from the British,2 and his role-integration within wider levels of the current Government), and underline his willingness to harmonize relations among all the diverse people residing in his domain, which had culminated in the amalgamation of both “Non-Onitsha Ibos” and Onitsha people within the new Onitsha Urban County Council over which he has since presided.3

The Obi is lauded as “a bridge between the past traditions of his people and their aspirations for the future,”for establishing the tradition of the past in the light of the modern age,” and (particularly in the Spokesman editorial) for developing a “crusade of peace and unity” that would eventually reach out to the world stage. Repeated references are made to his fatherly manner, his “approachability,” the “majesty of his bearing,” and his “personality (which) spoke louder than words.”

This metaphor of a personality speaking louder than words (and the Spokesman’s earlier reference to the Obi’s working “silently”) may be interpreted as veiled references to Obi Okosi II’s notorious inarticulateness in public, the social weakness for which he had been most widely (if only confidentially) criticized. He was admired for such traditional qualities as physical bearing (he was both massive and tall), the deep quality of his voice, and his approachability, but I had sensed a definite concern regarding his capacity to represent Onitsha people’s sense of their forthcoming significance as major leaders in the new nation of Nigeria — a capacity inseparable from the public use of articulate speech (including, prominently, English)4

Throughout these eulogies the use of Western concepts, metaphors, and literary allusions is very striking. Zik’s modifier “tragic” directs a reader’s attention to complex inner meditations by the mourner, while the NCNC’s New Testament quotation makes allusion to the Christian doctrine of Resurrection5 . And yet, despite such felicitous references and the general emphasis on the brotherly love claimed to be pervading Onitsha, the Onitsha Chapter of the NCNC cannot not resist pointing out “certain Principalities” who in the past “sold out” to become “obedient ‘Boys’ of the Empire”. The sarcastic reference introduces a note of intolerance into these generally expansive utterances, suggesting that such love cannot be indiscriminately extended — some do not deserve it.

The published eulogy nearest to a “traditional statement” is presented by John Oduah, the Igwe of Akili (a set of towns on the Niger floodplain near Onitsha), who after saluting the Obi with several of his traditional titles then says:

“The king that ruled with a smile and kindness has gone to rest with the Lord for ever and ever.

Okosi II is dead but his memories will live for ever.

Although he has been severed with mother earth but the dignity that was his demeanor will live for ever.

Although his magnetic frame we will see no more, but the link he made between Onitsha and other Ibos will remain unbroken.

Let the Lordly Niger hold its billows and flow silently in last respect to the great departed king.

Let the murmuring Nkisi and Idemili streams flow through their winding courses solemnly in obedience to the great King that has gone to rest.

Let misty Nsugbe Hills and Smokey Valleys pay him homage.

Let the swampy high forests in Ogbaru and Anambra Districts pay tribute to the great ruler of the Ibo land.

Let the twinkling stars and the moon exhibit their beauties in adoration to the king.

I call on all the Ogbarus and their graceful dancers to show their last respect to the traditional ruler of the ever hospitable and accommodating Onitsha.

I call on all the Nupes, the Igaras, the Hausas, Yorubas to gather to pay the last homage to the king of the land that has given us shelter and food for years undisturbed.

I call on all the industrious Ibo traders and businessmen to rally round to mourn their cheritable (sic) king that ruled without discrimination.

May he rest in peace.”

Interwoven with the superficially Judeo-Christian and Romantic imagery of these passages is an extended evocation of the Obi’s unique traditional position in the complex physical, biotic, and social/cultural setting that constitutes historical Onitsha, reflecting an awareness of the deep symbolic connections of traditional Kingship with the natural order that is part of the shared culture of the Riverine (olu or Ogbaru) Igbo-speaking communities for whom the author is giving voice, and of which they consider Onitsha a part.

The historical links of these Riverine Igbo-speaking communities to Onitsha reach into the legendary past (including trading relationships long before the settling of the Waterside by repesentatives of European power), and the Riverine peoples were among the first to reside as immigrants in Colonial era Onitsha. Having established relatively stable relations with the Inland Town, in the early 1960s they were consistently called “Riverine people” (ndi-olu) by Ndi-Onicha to contrast them against the “Ndi-Igbo” of the immediately adjacent eastern hinterlands who also spoke languages mutually intelligible among all three groups. In recent years the Ogbaru alliance with Ndi-Onicha has prevented the Ndi-Igbo from developing a fully unified “non-Onitsha Ibo” opposition to the Onitsha indigenes in the political arena of Onitsha Town, though Ogbaru numbers in Onitsha have always been quite small6 Note especially Chief Oduah’s singling out of the “industrious Ibo traders and businessmen”, expressly calling on them to “rally round” and participate in the mourning process. While they are placed last in this (perhaps hierarchical) ordering of the world, they are also — if somewhat condescendingly — flattered.

Chief Oduah’s eulogy also considerably expands the Onitsha king’s domain beyond its traditional range of the Onitsha community and contiguous farmlands, proclaiming him the king of all Igboland (a title which — as we would eventually recognize from our research — is historically more appropriately associated with the Eze Nri of the eastern hinterlands). No leaders or representatives of the nearby hinterlands Ndi-Igbo towns which were most strongly involved in the Non-Onitsha Ibos Association — Obosi, Nkpor, Nnewi, Awka and their neighbors — write odes of any sort to the Obi (at least none that are published in either local newspaper), and they would no doubt have rejected Chief Oduah’s expansionist representation of Okosi II’s powers.

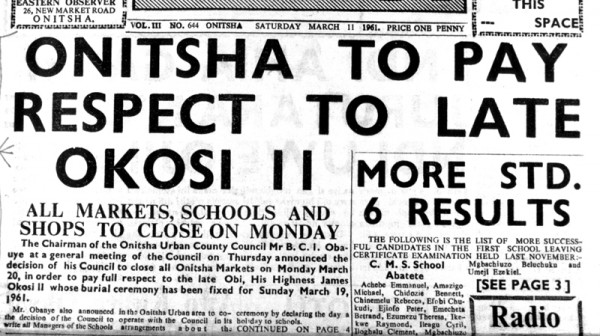

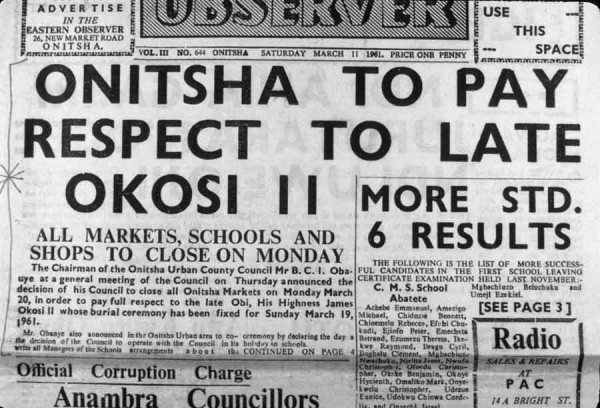

On March 17 and 18, the two local newspapers announce details of the imminent funeral. The Observer speaks first on the 17th, front-paging the OUCC’s decision that “all markets, schools and shops close on the following Monday”:

On the 18th, the Spokesman devotes most of the paper to various announcements and tributes,but also inserts the feature regarding market and school closure on the 4th page:

Both articles emphasize the point of “full respect”, “fitting tribute” as the basis for this public gesture.

The March 18 Spokesman provides a schedule of the “official events” of the funeral:

“Saturday evening: there will be a tolling of church bells;

Sunday morning: there will be religious services in all the churches;

Sunday afternoon: the N.C.N.C. Onitsha branch will offer a cow and purse to the king’s family at the palace square; the prominent invitees will arrive; the Onitsha senior chiefs will make their processions into the square; traditional dances will be performed by groups from neighboring towns; there will be a twenty-one gun salute; three appearances will be made by the Prince, representing the late Obi.”

The list — aside from its emphasis on European more than African traditions — is noteworthy, first, for its formal assignment of a ritual role, not to the Onitsha Urban County Council (whose members include representatives of the several political parties as well as of several non-Igbo-speaking ethnic groups), but to the dominant political party of Eastern Nigeria, the NCNC. While the OUCC takes actual charge of the major technical arrangements for the funeral, its own representation is of course dominated by the NCNC, and the latter takes most of the media credit for the spectacle that occurs en scene. Second, a prominent position is given not only to major actors among the Onitsha people but also to “groups from neighboring towns.”

The traditional conclusion of the formal announcements includes a series of ritual procedures not described in the newspapers, but which constitute the beginning of the burial process.

2. Obi Okosi II: Final Ofala

According to Onitsha tradition, the night before the ofala begins, The Obi’s ufie drums, a pair of sacred wooden gongs that are played every morning during his lifetime to assert the coming of the dawn, were now played in fading twilight, calling out in rhythm the names of ancestral Onitsha kings to notify them of the event. On this particular Saturday evening, a few hundred Onitsha people gather at the palace to observe this ritual while church bells are tolling through the rest of the town, . At the music’s end, Obi Okosi II’s name is for the first time included in the percussional sequence, and the most Senior Chief (Onowu) sends his Bell (mgbiligba) ringing around Onitsha Inland Town announcing the onset of Ofala. The men of Ogboli Olosi (ritually, they have a distinctive role in supervising any Obi‘s burial) proceed to dance the igba oziza — the “dance of anger” around the streets of the town that typically begins any man’s burial.

Morning Rituals

On Sunday morning, the main focus of activity for Onitsha traditional leaders (and for many other Onitsha people as well) is not the various memorial services conducted for the Obi in Onitsha churches but the ritual sacrifice of three cows presented by the Obi‘s primary descent group, the Umu-Chimukwu, to the people of Onitsha.

In the mid-morning heat Byron Maduegbuna and I walk down the paved street (Okosi Road) running past the sacred grove surrounding Obi Okosi II’s palace. In Onitsha belief, high forest is identified with most fertile earth, and by tradition Onitsha kings have always dwelt within a grove of high, sacred forest (okwu-eze).

Inside are the Palace Grounds, called ilo-eze (Public Grounds of the King), and the public entry into these sacred grounds is the onu-ilo-eze, the Mouth of the place. This point marks a passage between the everyday terrains of outside and the intensified places within, a passage marked by an overhead Medicinal Arch (Oda) designed to protect the King’s space from foreign pollutants. (Certain medicines (ogwu) are contained in the wrappings placed near the center of the arch, see above.) Along the flanks of the entrance stand the trees most closely linked to the Obi: the onu-egbo trees identified with him, with the sun, and other Spirits (alusi). Their lower flanks are painted white.

In precolonial times, slaves were sacrificed at these major tree shrines at this time. The King’s Head Slave (isi-odigbo-eze) was tied before the palace, and people entering the palace grounds would each gather a handful of earth, throw it upon him, and demand that he convey a message to one’s ancestors: for example, “tell them I am poor, I need more children.” This slave became onye-uma, a Messenger (to the dead). (The Nigerian policeman standing at right of course testifies that we are living in Modern Times.)

An enclosure (left) set up at the onu egbo entrance marks a location where, by tradition, the Head Mourner (onye-isi-ozu) would sit, administering his momentary power to confer the ozo title upon any man who had begun the initiation process but had not completed it. Any person in this liminal phase of title-taking who did not complete the title before the Obi’s burial must begin the entire process anew. (I am told that this custom is no longer actually being observed, but the enclosure remains on this day as a gesture to the past.)

At the distant end of the vast outer courtyard stands the palace complex (below), its visual focus the two-storeyed, gabled building containing the Obi‘s private quarters.

At left in the image is the arched entryway to the main royal courtyard where the Onitsha People (ndi-onicha) meet to enact plenary affairs. The mud walls are painted white and indented in places with abstract sculptured designs in black, red, and yellow (colors of the leoprd), its corrugated iron gable roofs an earthen red. In front of the main enclosure toward the right stands an elevated, gable-roofed open platform called “the King’s Breeze House” (uno ifufe eze), where he had retired the previous September to “enter into dreaming” to commune with the forces of the cosmos and the ancestors of Onitsha people (his customary duties during the climax of the year at harvest time), and where after his public Festive Emergence from seclusion last October he had sat robed in triumphal splendor on this richly decorated outdoor throne and received the salutes of his people.

On the morning of this final Festive Emergence day, the Breeze House (at left here) is empty but decorated with colored electric lights and pennants strung along its eaves by workers from the OUCC. The Obi’s twin Ufie drums are placed on the earth nearby (at lower right) where they had sounded Okosi’s name along with those of the royal ancestors the previous night. These drums are a potent symbol of the Kinship: in precolonial times they enabled the Obi to exercise control over people’s movements: in those days, daybreak would arise to the tune of these Drums, and it was said that any cock that crowed prematurely would be put to death. At the sound of the Ufie, the Obi would rise, bathe, and provide offerings to the Spirit shrines on the Palace Grounds. No Ndi-Onicha were allowed to roam beyond Onitsha Town before the sounding of these Drums.

Behind the Ufie Drums, and depending from the roof-beam of the Royal Breeze House, hang the Royal War Drums (Egwu-ota), a close-up view of which appears at left. These drums will play a central role in the rituals to come. (Here they have been pasted with some feathers indicating recent sacrifice.)

Dancings by Daughters and Wives

In the square before the Breeze House, two groups of women are dancing in separate circles. In one, the Women of the Children of Chimukwu (ikporogbe-umu-Chimukwu), wives of the Obi‘s primary lineage, dance grouped in a circle, in the center of which stands their Headwoman, beating the rhythms with her iron gong.7 In the second circle, the Daughters-of-Chimukwu (Umuada -Chimukwu), female members of the Obi‘s primary lineage, dance, clad in brilliant uniforms of black, red, and gold, while their Head Daughter (isi-ada), dressed in distinctive shades of red, stands in the center beating rhythms with her iron gong:

(Note the OUCC truck with men unloading folding chairs to be placed in the arbor at rear for the afternoon festivities.)

At left here, see their gorgeous dance leader brandishing a miniature golden curved sacrificial sword, emblematic of the group’s royalty.

At right, see her more closely:

The group representing the Wives of the Village also danced, in their own distinctive dresses, one elderly woman at the center beating an iron gong to guide them. Unfortunately, these images were lost during the years when I presented these materials in “slide show” lectures, which were dangerous venues for slide disappearance, and these did disappear.

While these women are perform their obligatory dances, we can see behind and to the right of the main building complex a separate row-house of single rooms occupied by the Obi’s own wives, who are now strictly secluded in mourning. In precolonial times some of them might by now have fled, and others might have been selected to accompany the king to his grave, but on this occasion a few are visible watching the Festival preparations at windows in their bedrooms.8

Workers are setting up a line of palm-thatched arbors running out from the palace along each flank of the square, to provide seating arrangements for distinguished visitors. The indigenes are to be seated along the right flank (as viewed from the palace), outsiders along the left, the two groups facing one another in opposition across the open square. The workmen unload folding chairs for these arbors from OUCC dump-trucks. while a scattering of people of both sexes and varying ages, dressed in fine clothing of many styles and colors, walk through the outer courtyard toward the palace to make their final salutations to the King.

We proceed past the Breeze House to the palace entry, walking through high, thick, whitewashed archway into the great open-earthed, colonnaded public courtyard where the Obi regularly met with the people of Onitsha Inland Town to discuss community affairs.

Recall the public courtyard in operation, as below, a view of Obi Okosi II seated on his royal throne (ukpo-eze) one night in the previous October, bestowing the Owelle chieftaincy title on H.O. Orefo of Ogbeotu (see Chapter 3, The New Nigeria, the page on “Power and Paradox in Onitsha”, scroll down to the Owelle title-taking for the full description.))

Killing Three Cows

On this day the king’s high throne (partly visible at far left in the image to the left) is empty and unadorned. Upon entering the courtyard, We find that the three cows have already been sacrificed, their heads decorating a space before the throne. These heads (and the skins and forelegs of the animals) are set aside for the Obi’s sons, to be divided among the immediate descent group, which had provided the beasts.

Seated on the bench immediately left of the throne, Chugbo the Akwue occupies the traditional space reserved for the Lesser Chiefs (Ndichie-Okwaraeze), He is the only representative of the Lesser Chiefs currently occupying this, their designated location, though others of this group are discussing meat division in the far side of the courtyard.

As the Prime Minister (Onowu) greets me from across the courtyard, inquiring why I am so late (I later learned that I could have blamed Byron, whose overprotective control over my schedule had produced this error in timing), men (at left) crouch in the brilliant sunlight of mid-courtyard, busy carving the meat of the three sacrificed cows and placing it on mats of banana leaves, to be divided for distribution to Ndi-Onicha. (The man in blue trousers to the left is Douglas Molokwu, a member of Ogbeotu who helped me in my research, assisting one of the hired workers to dissect one animal’s ribs.) By custom, the ribs of an animal are to be divided equally among the six Senior Chiefs (Ndichie-Ume).) The Prime Minister receives the heart, liver, and two hind legs as well. Two hind legs and the hips are shared among the remaining Chiefs (Ndichie), and the Daughters and Wives of Onitsha share the Waist parts. The rest is divided among the Ozo-titled and untitled men.

Along the RIGHT FLANK of the Throne:

At left, some of Onitsha’s most senior patrilineage priests (ndi-okpala Onicha) are seated in their customary place on the bank immediately to the right of the Obi‘s throne,

while beyond them along the right flank of the chamber and in front of the doorway leading to the king’s two-storeyed private chambers, men of the Obi‘s immediate family sat on the stairway (you can just see them here at far left, obscured by the workman) watching the division of meat.

In the picture at left, the Onowu (Phillip Anatogu) sits just left of the white pillar, beside his colleague Mbamali the Ajie, both dressed in white. To his left, beyond the white pillar sit men of the Royal Family (Umu-Chimukwu), led by Robert Okagbue (dressed in yellow), previously Obi Okosi II’s Personal Secretary. The Onowu is ensconsed in the senior position of the Senior Chiefs (Ndichie-Ume), just beyond the Royal Family along the right flank of the courtyard. (Note the children standing behind the two Senior Chiefs, all members of the Royal Family.) See a closer view of the three men to the right.

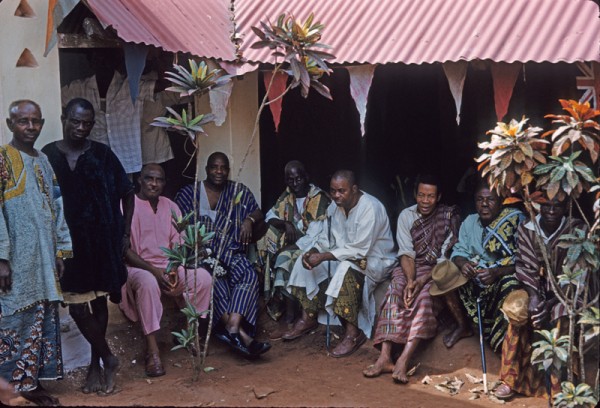

Prime Minister Anatogu now rises to direct the butchers’ division of the ribs into six equal portions (the share traditionally reserved for the six senior chiefs). In the image below, seated beyond him in descending order of rank are the Second Minister (Ajie), J.O. Mbamali (a retired senior Nigeria Customs official); the Third Minister (Odu), I.A. Mbanefo (a retired United Africa Company Accountant, now an independent dealer in palm kernels and widely known for his wealth and the prominence of his family); the Fourth Minister (Onya), Simon Egbunike (a long-retired Native Court Clerk, newly ascended to his post during the past year, the Onya covers his face in this image with his Chief’s Fan (azuzu ndichie); ; the Fifth Minister (Ogene), F. C. Nwokedi (a retired Nigerian Railway clerk), and the Sixth Minister (Owelle), H.O. Orefo (a retired clerk for the John Holts import-export firm, who had completed his title-taking just the previous October).

As may be seen, some of the Senior Chiefs hold their round leather Fans of Peace overhead to shield their bare heads from the brilliant sunlight flooding the chamber. Below, a closer view of the designs on the Fan Azuzu).

Beyond the Owelle at the far end of the courtyard’s right flank sit the junior or Ranking Chiefs (ndichie okwa), some of whom are also very prominent men in the community aside from their chieftaincy titles. Below, several of them are standing to argue over division of the meat, here including from left to right the Ogbuoba at far left, the Eseagba (back facing us, he a Lesser Chief), the Ojudo, the Adazie (face in shadow), and Asagwali);

Along the LEFT FLANK of the Throne:

Beyond the seating reserved for the Lesser Chiefs, along the left flank of the Throne toward the entryway seating is reserved for the Ozo-titled men of Onitsha:

and, at the far end beyond the entry archway, the place for the untitled men (Agbala-na-iregwu).

You will note that, around all the banks of the chamber, men sit bareheaded under a glaring sun — in this court, only the Obi might wear a cap (except on the occasion when he ritually bestowed one upon a new chief). The two most senior chiefs wear robes of white, while all the others (except for the butchers, clad in short pants and undershirts) are dressed in the brilliantly colored gowns (made of expensive cloth from Akwete in the Igbo hinterlands, of Kente from Ghana, or spectacularly decorated materials imported from England and the Continent) which constitute the standard “dress suits” (agbada) of tradition-oriented Onitsha men. Since every indigene is entitled to a share of the meat, and since shares vary systematically according to social status, some individuals from each set of participants are watching the division jealously to ensure that it is entirely customary. As I watch, the ranking chiefs and lesser chiefs argue over how some of the goods are being allocated, their voices rising in indignation.

By tradition seats are reserved at the far end of the courtyard opposite the Obi for the titled women of the Inland Town, but at this moment no women are sitting there. However, while we watch the division of meat, Onitsha women (and men) in various styles of dress are continuously walking back and forth across the yard on their way to or from the Obi’s private chambers, where the corpse is now on view:

The Route to the Inner Chambers:

As part of this procession, now the Onitsha “Ivory Association” (Otu-odu), an elite group of modern-titled women, led by their patron Chinyelugo Etukokwu, appear through the entry archway:

Above at left, the male patrons, all Ozo-titled men, carrying their iconic elephant-ivory horns (Okwuodu), enter the public chamber; above right, they turn to witness the entry of the Otu-Odu (Ivory Association), women who wear conspicuous, massive elephant ivory bracelets, the most senior women of the group dressed in white robes and burdened with very large, heavy ivory anklets, and necklaces of large red pipestones. Notice the Acolyte who approaches at far right, holding an ornate fan in his right hand.

Below left, the acolyte turns and hands her Peace Fan to Omenyi, the most senior of the Ivoried Women and one of the prominent Onitsha trading women of the past. (He holds her Otinri, horsetail switch of mourning, in his left hand.) Below right, Omenyi has danced past the camera and other Ivoried Women follow her in dancing.

En route to saluting the Obi, the Otu-Odu women first enter the next inner chamber of the palace (the Uno-ume, chamber ordinarily reserved solely for decisive consultations among the Obi and the Ndichie-Ume (the six Senior Chiefs).

There a line of people have formed awaiting admission into the inner, family chamber where the corpse of Okosi II now lies in state for viewing.9 Below left, the prominent Elder, Omenyi, dances in the chamber with some other Otu Odu women, holding her Peace Fan in her right hand. The black Horsetail Switch (normally carried in the mourner’s left hand) is draped over her shoulder as she dances. Below right, a young girl reveals herself to be a major Mourner of the Obi by virtue of holding her Horsetail Switch and wearing the large Pipestone necklace.

Below, from a position in the chamber on the far side of the Obi‘s throne, I am able to show some major freatures of the Uno-Ume, including carved side-posts representing the Obi‘s slaves, and a remarkable iconography on the back of the throne where he formerly sat to conduct conferences with the Ndichie-Ume. Various guests wait their turn to enter the family chambers off-camera to the far right.

Below left, a close-up image of the chamber’s far wall, slightly intensified to show the decorations, displays symbolism of the Throne (ukpo) of this room for higher consultation. The central figure is the Obi as leopard, holding above him as prey a human head. (The Obi is “He Who Waits for his prey to come to Him.” The two prominent X-marks lower down on the sides represent cross-roads where decision-makers meet. Were the Obi present at a meeting here, he would sit before this leopard figure facing toward us, with the Onowu (Prime Minister) seated bareheaded and to his right.

In the image above right, we see a view of this same chamber, published in an essay by the Onye-Onicha Frank Mbanefo in 1962.10 The overhead logo, which I did not see when following this funeral, indicates that the palace was dedicated in October of 1914 (World War I had been declared at the end of July; it’s hard for me to guess how much that was affecting Onitsha at that time).

The predominant visual impression for me as I watch all of these gatherings is the aesthetic impact of Onitsha people’s attire. Nearly everyone passing by (except for the two hired butchermen) makes — in the combination of cloths, designs, and colors worn along with other decorations — sartorial statements which seem to me highly sophisticated and pleasing to the eye.11

This intrusion of diverse crowds of visitors into the Uno-Ume — and worse, waiting there to enter the Agbala-eze, the Obi‘s private familial chambers — is entirely contrary to precolonial custom, when these spaces epitomized the Onitsha concept of nso — “sacred, forbidden” places where ordinary people would be greatly afraid to go.

But today, the quiet and orderly crowd waiting to view the corpse grows until it extends well out across the public courtyard, where (out of view) the chiefs are distributing the last parts of the meat, and all who have attended the sacrifice (including myself) are eventually sent home with at least one piece of meat wrapped in a strip of banana leaf.

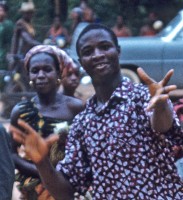

I confess I was repeatedly struck by the face of this woman whose image you also see in the picture directly above. I saw here at several points touring this day, and each time she wore a face so filled with sadness that it was hard to look away. Unfortunately I never managed to learn who she was in the sphere of Onitsha community.

Having participated in the distribution of the meat, we later join in the line waiting in the Uno ume, and like the others are allowed to enter the Agbala-eze, the broad concrete stairway leading to the second storey of the king’s chambers. We look down into Agbala-Eze, where the Women of Chimukwu are organizing division of their share in the meat of sacrifice. The standing woman wearing a white shirt, the Isi-Ada (Head Daughter) directs the process, while other Daughters sit around the flanks of the chamber. In the image at right, notice the shrine to the householder’s Personal God (chi), in the form of the egbo tree in the upper central part of the photograph (with its surrounding shrine objects).

Those images are captured from the landing above the chamber. At the top of the stairway, the corpse of Obi Okosi II rests upon a large brass bed:

Guarded on both sides by Daughters of Chimukwu (umu-ada chimukwu), the body is covered with pure white bed linens and clad in white (including white gloves), with faintly red-embroidered ruffles down the front of the gown. His head, wearing a pure red cap, rests on a sumptuous white bedding, and his eyes are filled with white clay. Placed at each side of the great pillow are two heavily embroidered, mostly European-style crowns, one gold-on-red, one gold-on-white. A strong aroma combining european-style perfumes and the stench of death fills the air. The content of this scene appears strongly European — the clothing materials, the brass bed and its coverings, the British-style crowns and the imported red-felt fez introduced in early colonial times as a sign of “red-cap-chieftaincy”.

However, a closer look shows some older elements: The color coding is in a sense “traditional” (the black/white/red/yellow elements of leopard coloring), and the eyes covered with White Clay (Nzu), an icon of the Forbidden (nso) identify the Obi with Spirit, ghostly power. While the Crown on the left appears to sport a cross on the top, the golden one on the right is topped by an abstract bird (while the figure below it looks like a fleur-de-lys), and the “arch” pattern links it to the mmanwu (Incarnate Dead). Attached to the red cap, depending downward, is a set of black-tipped white feathers, the primary feathers of the Ugo (Gypohierax angolensis), the “Vulturine Fish Eagle” or “Palm Nut Vulture”, the most sacred bird of this culture, identified as the top bird on the Iroko tree, the “Mighty Tree” (Oke-Osisi) of Onitsha Kingship.

As people approach up the broad concrete stairs toward the foot of the bed, they present money to the Head Daughter (Isi-ada) of Umu-Chimukwu, who sits by the foot of the bed holding a traditional bowl, which today is packed almost to the brim with coins and pound notes. The visitors then kneel and salute the Obi as “Sky” (igwe), touching their heads to the bed. As a long line of mourners move slowly through the intensifying heat of late morning, I wait my turn and contribute a pound note to the Daughters, the amount Byron considers appropriate to my social status.

Outside, The NCNC political committee presents a steer to honor the Obi:

To make this large group somewhat more visible, I divide the image into two parts:

Afternoon Rituals

1. Gathering the Bodies

Away from the palace in the Waterside along New Market Road in the early afternoon, we see from our Fiat 600 vehicle two men walking along the street, dressed like Hausa men (though they are Ndi-Igbo) and escorting a large, rotund masquerade figure whom they assiduously attend and fan (left). The face of the figure is that of Sir Ahmadu Bello, the Sardauna of Sokoto and Premier of the Northern Region. When we try to photograph the face of this figure, his acolyte quickly hides it with his fan (one cheek of the mask is just visible below the hand holding the fan). Though the “Sardauna” moves near the edges of the Inland Town, in a sense representing the Northern leadership of the current coalition National Government, he never enters the palace grounds.12

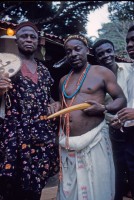

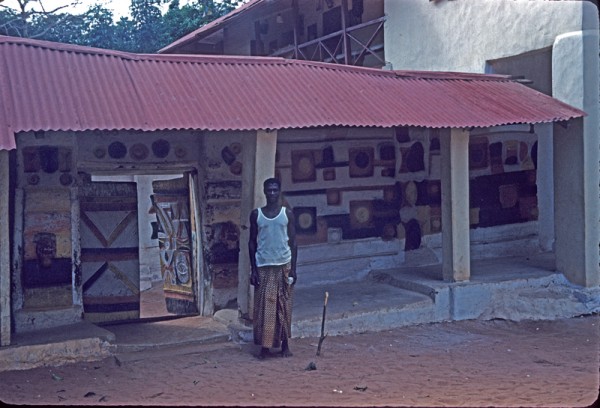

One of the most remarkable figures who actually does enter the palace grounds early in the afternoon on this Festival day is this man at left, a dancer from Awkuzu, one of a string of towns northeast of Onitsha that share with Ndi-onicha old connections with the town of Aguleri, mythic origin site of the first Nri King (Eze-Nri). His dance takes the form of a slow, walking motion, in which at all times some part of his body is flowing in continuous gestural movement.

Lacking a vocabulary to describe the qualities of this remarkably hypnotic dancing, I can only bemoan my lack of a movie camera and move on. His face persistently holds the same fixed smile you can see more clearly on this image to the right.

Crowds begin gradually to fill the square. In the image below right: on the right flank (nearest the Palace entrance), titled Onicha men and women take their seats of honor at places designated for them beneath the arbors. (See Chinyelugo Etukokwu toward the right, now wearing his Ozo cap and Ugo feather, sitting with the other titled patrons of Otu-Odu.) Below left, the more junior Otu-Odu members (those wearing only ivory bracelets) have appropriated seats officially designated for Onitsha’s Ozo titled men (Ndi-Agbalanze). Nobody will dare confront them.

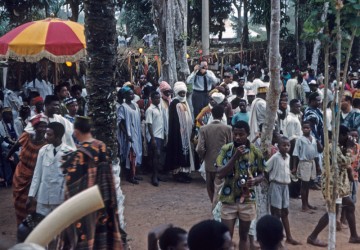

Locations along the left flank (looking out from the palace are reserved for people from the European and Asian communities, local church leaders, Eastern Region Government officials and their families. Early in the afternoon, people have filled most of these spaces.

Chief Nyong Essien, the Obong of Calabar, President of the Eastern Region House of Chiefs and the Eastern Nigeria Premier’s designated representative for the occasion, arrives at the head of a stately procession and takes his seat before a left flank arbor under his large embroidered umbrella.

I’m unsure exactly when this marching array of chiefs from towns outside Onitsha came marching through the palace grounds, but in retrospect the likelihood of imminent extinction of all Anam-lowlands elephants might well have entered my mind (though it didn’t at that time).

In the image below, an Onitsha Age-Grade (ogbo) passes the Obong as he heads toward his seat of honor. The Age-grade is going to salute the official Mourners.)

Various Onitsha Age-grades, each having affiliation with one of the Obi’s mourners, enter the palace grounds in their squadron formations, wearing distinctive uniforms, and dance their way to the Breeze House where each group salutes its associated mourner. Below, see the Ogbo Douglas Age-Grade, a very prominent group named after the first Onitsha District Officer, H.M. Douglas, who administered the area at the time these people were born (1906-1908). Men and women dance together in the contemporary age-grades, with an Ozo-titled man leading the way. Note that women, who lead the way beyond the rest of the men, make up a much higher proportion of the local group than do the men of this age level of (roughly) 53-55 years. This is a function of the fact that many Onitsha men are currently (1961) employed in civil service and other occupations elsewhere in Nigeria. (This is one of their outstanding distinctions.)

Below left, the Douglas Age-grade, supporting one of their members — a daughter of the late Obi (dressed in blue and carrying the Otinri as a sign of mourning) — arrive at the palace where they join her in saluting some senior Mourners before the Breeze House. (Note how some of the dancers in the rear continue dancing to the orchestra provided by the age-grade men.) Below right, as the Douglas Age-grade is completing their ritual circling of the Palace Grounds (in the far distant right), another Age-grade is entering the palace grounds at left-center.

Each of the genealogical daughters of the Obi dance into the square, holding her black horsetail fly-whisk of mourning, some accompanied by her age-grade, the whole group saluting the Head Mourner in front of the Breeze House. Below, at far right, Madame Ibekwe, wife of Nnanyelugo Ibekwe of Odoje Village, dances in, wearing a massive coral necklace and holding the otinri, accompanied by her gorgeous daughter (at left-center, dressed in blue) and other representatives of her husband’s descent group.

As I said above, members of Zik’s NCNC political party, Onitsha Branch, had gathered to present a steer to the Children of Chimuwku. At right, the Head Mourner (Onye-isi-ozu), Ononenyi Gbasiuzu Okosi, stands before the Breeze House, holding his ivory staff as Senior Lineage Priest (di-okpala), awaiting their presentation. Having removed his modernist Agbada attire, he is dressed in the late 19th-century style for the Head Mourner.

At left, I am talking with Jerry Orakwue, a well-respected local historian who is very helpful in my research. Close beside the Breeze House to its left, OUCC workers have constructed a temporary elevated platform to accommodate photographers and other representatives of the press. Jerry suggests I take advantage of the photographers’ platform to the right of the Uno-ifufe, which I do (to my great advantage, since the crowd becomes huge, and those stuck at ground level will see very limited ranges of the scenes).

As the crowd swells into a vast mass, the age-grade groups find their pathways increasingly congested — note the reddish-uniformed group in the foreground, below left (with their orchestra of age-grade men bringing up the rear). Groups of policemen are called into action, pushing the crowd outwards so performers have a bit of space to dance near the Breeze House. Below right, an orchestra accompanies one of the groups dancing beside the Breeze House.

A standing cluster of Onitsha elites gathers along the left flank of the palace grounds between the press platform and the left-flank arbors. Below, B.C.I. Obanye, an Onye-Onicha who is currently Chairman of the Onitsha Urban County Council, gives directions to a visiting dignitary, while other red-capped chiefs from visiting communities approach. Note how those occupying the highest outsider-elite seating under the arbors already find their viewpoint of the performane grounds entirely obscured.

At left, an assortment of expatriate government officials and businessmen (including the American Businessman George Russell, the head executive directing the new Pepsi-Cola bottling plant being constructed on the edge of town, dressed in orange and black Agbada at lower left in the image; unfortunately his back is to the camera), milled about near the clustered representatives of the Moslem communities residing in Onitsha.At right, the Onitsha District Officer, the Town Clerk (C.O. Okoli), Assistant Town Clerk, and an unidentified European administrator confer in the presence of Mrs. Russell (at far right). (A number of Eastern Region Ministers of State, heads of the judicary, and Provincial Commissioners attend the funeral.)

Some wear formal richly variegated European dress and bowler hats, others flowing agbada gowns with embroidered Hausa fezzes or Soviet-imitation-fur caps. The half dozen turbaned representatives of the Muslim communities living in the Waterside (at Ogbe-awusa, “Hausa Village”, and other now-remnant Moslem-affiliated villages) arrive late, in a single group, and stand somewhat aloof in a cluster in front of the left arbor. Soon the people who occupy the reserved seats of honor under the arbors find their views of the square entirely blocked by massive standing groups of men, and after a while the burgeoning crowd on both flanks of the square (which included not only many roughly-clothed men but also innumerable children) entirely obliterate the view of those who have chosen to sit in the chairs provided. They are now largely limited to observing each other. Only those of us who have climbed onto the elevated press platform find relatively unobstructed fields of vision. (Thank you for the good advice, Jerry Orakwue of Blessed Memory….)

2. Aguleri Hunters Fire Guns, Mystic Antelope Parades

Finally, a dancing group from outside Onitsha appears — from the Ogbaru/Olu town of Aguleri, and the police have to push the crowd aside vigorously in order to open a space of sufficient size near the Breeze House where the dancers can begin to perform.

At left, the Aguleri group of Ogbueni-Oba — Royal Hunters Association, said to be a Benin-linked organization, culture-borrowed from Ndi-Onicha along with the Kingship — enter the main arena, led by their Antelope Masquerade escorted by raffia-skirted drummers and warriors. At right, the warriors fire off shots with their matchlock rifles (Dane Guns) into the surrounding trees as they dance, filling the air with noise and gunsmoke (and an air of uncertainty for some, since these weapons are of uncertain provenience and condition, and are known to explode when triggered). The Antelope Masquerade stands in silhouette at far right.

The King of Aguleri (an important Anambra River trading community, “Riverine People” (Ndi-Olu) culturally related to Onitsha and (more closely in old-historical terms, to Nri) also sent several of his red-cap Chiefs to greet the Head Mourner. Aguleri owes its Kingship in recent times to the Onitsha Obi, and these two royal figures maintain respectful relationships.

In the image at right, the masquerade dances, swinging its skirts. Note another masked figure just visible In the image at near right. In the image at right, the crowd has closed in on the dancers, while the visiting chiefs (red caps with feathers) salute the Head Mourner. (See Historian Jerry Orakwue observing the process at close range, lower left.)

Below, Gbasiuzo Okosi leads the dance team offstage to its resting place, where it will receive refreshments.

3. Chiefs Arrive with Cannonades

As the first Onitsha senior chiefs approach the sacred palace grove, an array of small mini-cannons (“petards”) are to be detonated sequentially along Okosi Road on both sides of the palace entryway. Petards are cannon-like devices dating from medieval western Europe, bell-shaped iron powder-holders with fuses attached at the base. Onitsha people have hired a collection of them to fire off as the Onitsha Senior Chiefs — Ndichie-Ume — approach the Palace Grounds, escorted by men of their respective major villages.

At left, local boys guard some of the petards; at right, a man sets off one of the faux-cannons at the 1959 Ofala of Okosi II. (Note the location just inside the palace grounds, and the main crowd in the far distances.)13

As the Senior Chiefs approach, smoke from the gunfire billows up near the Palace entryway and gradually disperses.

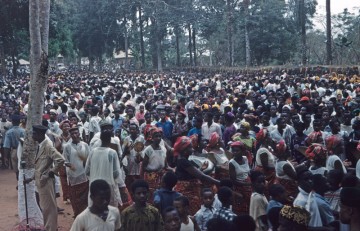

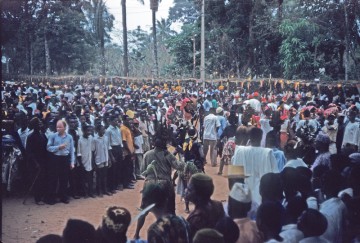

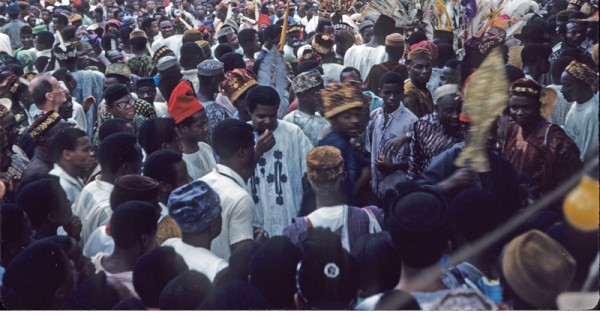

The image below shows a simple fact of the situation by the time the Ndichie-ume and their groups arrive: the entire palace grounds are completely packed with human bodies, following a substantial failure of crowd control. Some policemen are present, but Ndi-Onicha themselves have made no provision for organizing the masses of people who have come either to participate in or merely to observe the rituals. If you look closely in the distance, you can see some of the Ndi-Onicha Age-grades caught, and some partially dispersed, among the mass.

Thousands of youthful Ndi-Igbo traders, laborers, and schoolchildren from the Waterside join with Ndi-Onicha, European expatriates and other foreigners to form a dense throng which not only fills the palace grounds but overflows into the surrounding forest and out into the street, numbering in the tens of thousands. Perhaps three times the normal total resident population of the entire Onitsha Inland Town is here gathered to witness the final drama. Notice the representatives of the Muslim community in the lower-right foreground, jostled among the diverse individuals surrounding them.

The climactic moments of the Onitsha Festive Emergence ceremony now begin, as each of the Onitsha senior chiefs, wearing his elaborately feathered Great Crown, is escorted into the palace grounds by the other red-cap chiefs and men of the village he represents. In an ideal ritual situation, the chief (wearing his Great Crown) and his village men (including subordinate chiefs wearing red-caps) form a compact, unified group reflecting the structure of the Great Headdress itself — the Headress figuring a Great Tree surmounting a mound of earth and bristling with feathers representing the clustering and perching birds and other creatures who find refuge and nurturance there (his red-capped chiefs and other escorting village men, the whole image comprising a synthesizing symbol of Onitsha leadership).

As the group marches forward in unison, the senior chief periodically forays out from it in brief dances, confonting the onlookers with his flashing Ceremonial Sword, in challenging warlike dance. When they arrive at the Breeze House, he touches his sword to the Royal War Gongs, dances to their rhythms, silences them with the same gesture, then afterwards retires with his fellows to the right flank of the courtyard immediately beside the palace entryway, where they sit among the other chiefs and await the Emergence of the Obi from his palatial seclusion. In a normal annual Harvest Festival Emergence (one I had witnessed the previous October), they would come forth wearing the most magnificent Great Tree Headdress of them all, and proceed to dance around the palace with his Senior chiefs (now in red caps), who cluster around him in centripetal support, a visual modelling of social unity and centering.

On this occasion (in contrast to the Emergence of the previous October, when ample space had been available for the standard ritual procedures to occur in the palace square), the crowd of onlookers has become so vast and dense that neither police nor Inland Townspeople can effectively control them, and the orderly pattern of entering processions cannot occur. As the chiefs now proceed through the tight-packed crowd, they and their village supporters become separated from one another and engulfed by the spectators. The clustered groups of Onitsha village men are dissolved in the milling chaos of individuals of varied backgrounds, ages, and social status.

At left, the Onya, 4th senior chief from UmuEzeAroli, is escorted by Chukwudebe Adazie (with red cap, holding his brass spear, immediately to the Senior Chief’s left). At right, the Onowu (Prime Minister), of Ugwunabamkpa, at upper left in the image, has been separated from his more junior chiefs — the Odua (of Iyiawu sub-village), at left foreground, and the Asagwali (of Umuase) is lost in the crowd, barely visible at flower-middle right.

Slowly each senior chief manages to make his way toward the Breeze-House where the Royal War Drums are kept. A small opening is cleared to the left flank of that space, near the cluster of richly-dressed businessmen, lawyers, government officials, and other members of the educated elite. There the senior chief dances before them, encouraged by their shouts of praise and enthusiasm and their occasional echoing of the traditional leaders’ performances with their own dance movements. At left, the Onowu performs his at the head of the cluster of other Senior Chiefs, while they await their turn. At right, the Owelle, the most junior of the Senior Chiefs, having danced for the elites, moves slowly through the crowd toward the Royal Drums.

In the final formal dance, each Senior Chief will touch his ceremonial sword to the royal war drums, and dance to honor the deceased Obi. Below, the Owelle is shown completing this performance. The brass color of the sword is visible, slightly blurred right of his body as he thrusts it toward the drums. .

Then, after again touching his ceremonial sword to retire the royal war drums, Each Senior Chief goes to the right flank of the palace near the archway, where his Great Headdress is removed — as shown for the Ogene, below.

As each chief takes his seat, the collection of Great Tree Headdresses accumulate on the arbor overhead until the place where they sit looks like the nesting places of innumerable great birds.

Senior Son Strikes the Last Drum

Finally the senior son of the late Obi Okosi II, Joseph Okosi, strides out into the throng, wearing one of his father’s crowns. However, rather than (as in an annual Ofala) appearing wearing the Great Headdress, and then encircling the entire palace square with the chiefs surrounding the central figure (as the living king would do at the normal Harvest time ritual) the prince merely walks to the front of the Breeze House, where the senior son (accompanied by his brothers wearing various of Okosi’s ritual hats) takes up his father’s Ceremonial Sword and dances the final dance of Obi Okosi II’s reign:

As shown in the image above, when the prince finally touches the dead king’s sword to the war gongs to silence them, the funerary celebration is at an end.

Gradually then the huge crowd begins to disperse. As I climb down from the press platform to meet my friends, I think how ironic it must seem to the Onitsha people, so intent on preserving their traditions from incursions from without, to have their greatest ritual invaded by this flood of people which include so many foreigners. My anthropological colleague, the late R.E. Bradbury, who had driven to Onitsha from Benin to witness the funeral, voiced considerable surprise at the apparent disorder of the event in comparison with the highly structured and physically segregated ritual performances he regularly witnessed at Benin (which Onitsha people claim to emulate in forging their own kingship). One of the expatriate Anglican churchmen who attended the funeral later stated that it was a “typically Ibo” celebration, whether that of a traditional ritual or a “party” held among the contemporary elite: these social gatherings, he maintained, consistently display evidence of a formally structured model for procedure at the outset of the drama, but social status boundaries are rapidly breached in the developing situation as the mass of people refuse to “keep their appropriate place” and flood the scene in what quickly becomes a clamorous disorder.

When I ask Onitsha people about their impressions of the celebration, however, I encounter no trace of displeasure at the swamping of the primary actors by the centripetal pressuring of masses. Was not the attending crowd surpassingly huge? Did they not include people from all walks of life and all parts of the world? And did these facts not indicate the central and increasingly powerful significance of the Obi of Onitsha in the global scheme of things? Onitsha people express pride in the sheer human scale of this Ofala, the degree of respect indicated by such a turnout. All Onitsha funerals should indicate the range and complexity of the deceased’s involvement with others (and the greater this is, the greater the funeral).

Several points of interest seem relevant to me. First, find it odd that, despite the written scheduling of “dance groups from neighboring towns”, the only non-Onitsha dance group to attend the funeral came from Aguleri, a town located at a considerable distance from Onitsha (though Onitsha people claim that all of the immediately neighboring towns derived their own, recent chieftaincy customs from Onitsha, and “pay it tribute” on major ceremonial occasions). The single male performer from Awkuzu falls into the same category of Nri-linked towns (though no representative from Nri itself was evident).

Second, aside from the inadvertent effects of crowd size, the formal patterning of the ritual somehow proclaimed the disintegration of the chiefs: instead of a final clustering, they each entered and performed while escorted by their separate village units and never combined as an active whole. This might appear symbolically appropriate, since the Interregnum announces a time when villages will unfailingly assert their separate interests and wills.

On the other hand, at the climax of the ceremony a nice formal balance had evolved between the traditional chiefs, who ultimately seated themselves on the right flank of the palace, and the visibly “modernistic” elites (including both Onitsha and non-Onitsha people), who stood far over on the left. When chiefs entered the palace grounds and moved down the left flank, before crossing over to the center (at the Obi‘s Breeze House, his place of communion with the forces of nature) to perform their ritual dances, the Senior Chiefs with their Great Tree Headdresses were each approached by the modernistic elites, who saluted them and praised their dancing with exuberant, energetic enthusiasm. At these moments, the educated elite accorded the traditional leaders high-intensity and very public measures of respect and regard.

The fact that new and old elites might celebrate each other on this occasion was unsurprising, but other meanings lurked in these processes as well. The absences seemed significant, as well as the strength of leadership being signaled (in terms of ritual-oriented crowd control).

3. Backstage Moments and Broader Observations

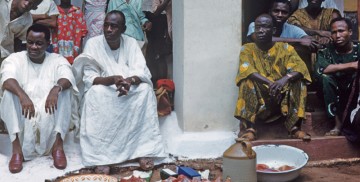

As the Ofala crowd departs, I meet with one of my Odoje Village associates, Nnanyelugo PaulIbekwe, and his wife, a daughter of the late Obi Okosi II. I want to inquire whether I might attend the Obi‘s burial, which I know will take place this same night, and Nnanyelugo has a strong relationship with the Head Mourner, Ononenyi Okosi of Umu-Chimukwu family. After I photograph the pair (at left and right), Nnanyelugo escorts me alone to meet with Ononenyi, who is still receiving funerary visitors — an Obosi town chief, who has come to greet him late and in private, has brought him a bottle of Scotch whisky as a funeral gift, and is conversing with him as we enter the private, royal family courtyard. This Obosi man has the notewothy reputation in Onitsha as a “chief of thieves” (whatever that may mean in practice).

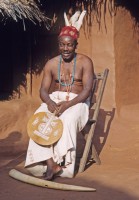

The Obosi Chief having departed, Nnanyelugo Ibekwe deems the moment suitable to photograph the Head Mourner in his ritual attire, including his Ozo title cap, peace fan, and Odu ivory horn.

As Ononenyi prepares for the photo, I cab observe that his eyes are glazed and his speech quite slurred. By that time, I have lived in Onitsha for some seven months, haved witnessed a variety of rituals and am beginning to understand that this is an unavoidable condition for those men whose assigned task is representing the practice of what most elders describe to me as “Native Law and Custom”. For the priests who occupy the most important ritual thrones of the community. a prime task is to accept a considerable sequence of ritual alcoholic drinks from each of the authoritative parties attending, and to partake of each of these offerings themselves (after first offering them to the relevant spirits and ghosts) while sharing them with other appropriate participants.

The longer I work in Onitsha, the more I attend substantial public ceremonies, I too experience the effects of such participation. For example, the Prime Minister (Onowu) especially enjoys calling me to accept glasses of strong drink from his hand (partaking as one squats before the authority figure signifies one’s status as a kind of dependent), and when I am present at an event of any degree of elaboration, I sometimes find myself gradually losing focus as the ritual progressed. Not the best condition for serious ethnographic observation.

While the ancient formal gift patterns were based on palm wine as an offering of drink to the dead (the Obi himself symbolically embodied an identification with palm wine, which he was expected to drink in large quantities), with the coming of European trade goods people added other forms of alcoholic drink to the liturgy. By 1960, beer of various kinds had become important, but by far the most important drink was Schiedham’s Schnapps. The first time I heard of it — and then tasted it — was in Onitsha, but by the time I left Nigeria I viewed it as the emblematic ritual drink for Ndi-Onicha along with palm wine itself.

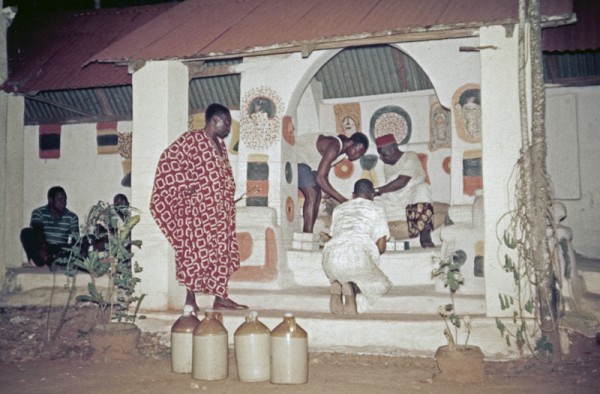

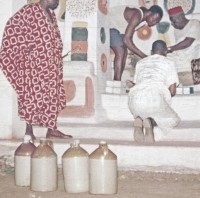

At left, recall the scene of Obi Okosi II bestowing the title of Owelle upon Akunne H.O. Orefo in October 1960. Four jugs of palm wine stand on the ground before the Throne, while the Owelle candidate kneels before the Obi. These of course comprise a truly ancient ritual drink of this region. But note too, just to the right of Orefo’s right elbow, two bottles of Seaman’s Schnapps in their characteristic blue and white boxes (his offerings to the Obi as part of the requirements for taking the Owelle title). Third, to Orefo’s left are four white-painted adobe blocks, which represent the persisting centrality of Schiedham’s Schnapps in relation to Obi Okosi II’s throne — symbols of that particular drink itself, the only objectification of ritual objects that was seated permanently on the floor of Obi Okosi II’s Throne.14

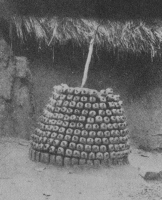

In various Igbo-speaking areas around Onitsha in the early 1960s, I saw many old shrines containing aesthetically-constructed accumulations of empty Schnapps bottles, and one truly monumental object I encountered was a massive glassy cylinder made entirely out of them, stacked around a moderate-sized ritual tree to the height of nearly three feet. (See also the image at right)15

That afternoon, we sit down with Ononenyi and his junior brother, and I make my request to be allowed to witness the burial of Obi Okosi II that coming night. In response, Ononenyi brings out his copy of C.K. Meek’s book, Law and Authority in a Nigerian Tribe (1937), and proceeds to read aloud from the text portion recounting the burial of the Onitsha Obi, which describes a custom of offering three slaves to be killed (now substituted for by the killing of the three cows), and emphasizing the requirement that the Children of Ogboli Olosi — and only they –are allowed attend the burial. Therefore, Ononenyi concludes, I will not be permitted to observe the ritual process.

In my one personal meeting with Obi Okosi II in October 1960 (he then accompanied by his Ndichie-ume), the Obi too had brought out his copy of the same book by Meek and read out responses to some of my questions. What I slowly began to grasp over the many following months was a central fact of contemporary Onitsha life: the most substantial Onitsha men — the men of title — are Western-educated, and many have spent large portions of their lives outside the Inland Town. They rely strongly on whatever written sources they have available to inform them about “native law and custom”, prominent among these Meek’s book but also including various colonial-administrative reports, court cases, and numerous other documents. A number of prominent people hold substantial filing cabinets containing such documents, which they can consult when deliberating issues of culture history. Documents and books are prize property for those who seek to know the truth, and — because culture history is important in local political economics — such cabinets are guarded.

Despite this growing written literature of cultural knowledge, by the 1960s few people (if anyone) can validly claim anything like comprehensive knowledge of pre-colonial Onitsha culture history, since the Inland Town community has been so altered (and its members so substantially dispersed) during more than 60 years of colonial experience. Men raised as school children under the missionaries, later becoming government clerks in other parts of Nigeria, often retain very limited contacts with their less educated, often illiterate elders, and in a sense many of them have to grasp at straws to piece together a fabric of knowledge and performance, in an expanding urban situation where Onitsha culture nonetheless remains pivotally important.

Most of the Senior Chiefs, for example, do not accurately perform their characteristic dance, which prescribe a clear and precise series of movements. (Their deviant steps wae accepted by most onlookers as testaments to a chief’s prerogatives of creativity.) So, at the same time that rapid social and cultural change in Onitsha makes Onitsha leaders want to lay claim to their heritage of valuable cultural knowledge, they have been robbed of this knowledge by multiple circumstances and have to engage in creative constructions.

One might argue that Ononenyi on this occasion merely wanted to put me off, and used the book as a prop to lend authority to his decision, regardless of the extent of his own cultural knowledge. This is a reasonable inference, but my consistent experience since the beginning of work in Onitsha has been that knowledge of Onitsha Old Culture was severely — perhaps irretrievably — scattered, beginning in the early colonial era, and everyone in that community was and is now deeply affected by this scattering.

For that matter, I, too — a graduate student, would-be professional ethnographer — had to deal with my own knowledge deficits as I worked to develop a picture of Onitsha culture and society. By the time Helen and I arrrived in Onitsha, I had of course read Meek’s book and consulted a number of other library sources, but I found myself seriously underprepared for the world I encountered, and (for example) read G.T. Basden’s seminal (1938) book Niger Ibos only while residing in Onitsha (and thanks to the library of Anglican Archbishop C.J. Patterson). Some really important documentary sources I encountered only years later. I began my fieldwork with what I now have to regard as an inappropriately shallow knowledge base, considering the complexity of the objects of research, and to a considerable degree I blundered about trying to build a better one.

My assessment today, in sum, is that all of us who have sought to explicate Onitsha in any of its historical dimensions have been and are looking through a glass darkly, trying to figure out the past in a place where it has receded from view too fast, making individuals incompetent to fully grasp it. A great many sources remain available, but each one of these is very weak in many regards.

Anyway, the four of us sat together in the evening after our brief discussions, drinking Nigeria’s own Star Beer, a product modeled on Heineken’s and definitely adequate to most informal gatherings.16

Some days later, I visited the late Obi’s senior son, Joseph Okosi (Amalunweze), who showed me the burial site. I met him in the Public Courtyard, below — now and for an indefinite future an empty space. (Only some 30 years later — in 1992 — did I see the palace in real time again, when it had become a very messy motor park, and then my escort deemed it unsafe to look closer.)

Joseph Okosi confirmed that — as I had heard in the meanwhile — the Nigerian Police had been present to witness the burial. He then escorted me around to the Obi‘s Ukoni — the Royal Kitchen — where, along its flank beside the door to his private quarters, the grave had been made.

(The close-up image at left leaves an odd illusion that Mr. Okosi’s neck may be deformed. This is due to the shadow behind him, darkening space behind his neck as he stands there against the whitewashed wall. He is in fact a handsome, well-formed man.)

Aftermath: Onitsha (Ndi-Igbo) Market Traders and “fitting tribute”

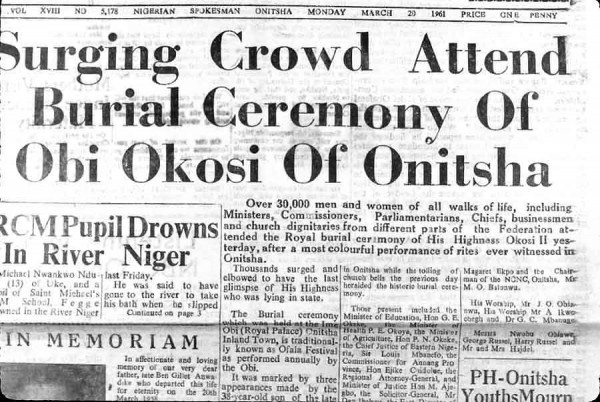

On Monday March 20, the Nigerian Spokesman trumpets the massive dimensions of the funeral, along with the prestige of the Regional and National officials who attended:

The reporter’s statement that the ceremony “was marked by three appearances made by the 38-year-old son of the late Obi, Prince Joseph Okosi… who was clad in the full regalia of his late father and flanked on both sides by the Ndichie Ume… moved with the grace and Royal elegance for which the late Obi was noted, inspecting the subjects on each occasion” is pure fantasy (see the previous section), as are the “over twenty-one native dances and fourteen Age Grade Societies” performing at the event. However, the estimate of total numbers in attendance does seem reasonable.

However, the Obi’s final funerary Emergence does not officially conclude the public funeral, which is expected to continue on this Monday. On the back page of the same Saturday, March 18 issue of the Nigerian Spokesman which presented the forthcoming funerary schedule, a large headline also announces:

The fact that this weekday cessation of the economically most salient activities of Onitsha town is being mandated by the NCNC ruling majority of the OUCC is explicitly emphasized by the Eastern Observer under its own front page headline of the same day:

The Observer specifically remarks that the purpose of the order was (as Mr. B.C.I. Obanye, the Onitsha indigene who is Chairman of the Onitsha Urban County Council, has reportedly put it) to ensure that everyone in the town “pay full respect to the late Obi.”

In the face of this officially designated notice, the (overwhelmingly) Ndi-Igbo traders in the vast, iron-gabled caverns of the Main Market of Onitsha open their 3,000+ stalls on Monday morning for business as usual. When the Main Market Superintendant, Mr. Osaka, sends bell ringers around the Main Market to notify everyone that the traders should close their market stalls on this day, agents of the newly renamed Onitsha Market Traders Association (OMATA), an organization of recently burgeoning power in the main market and beyond, dispatches a second bellman in the footsteps of the first to tell the traders to ignore the previous command. Consequently, the Onitsha markets hum with their usual daily activity, involving thousands of Ndi-Igbo traders and many thousands of their customers.

On Tuesday March 21, the Eastern Observer trumpets the facts:

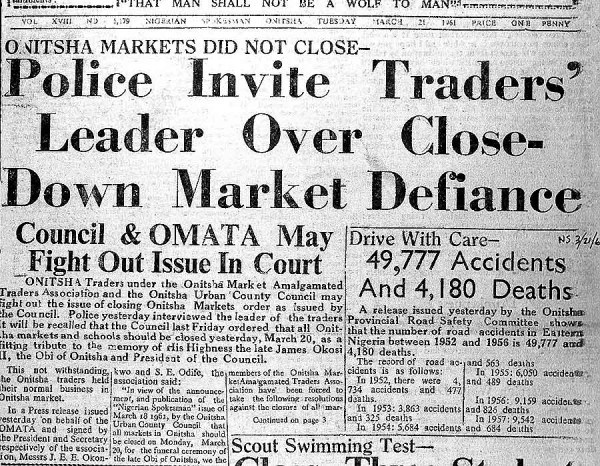

The Spokesman carries this banner headline:

The Spokesman article says the police have asked the President of the Onitsha Amalgamated Market Association to explain why the city Council’s order was disobeyed, and have demanded a list of the names of all traders who violated the order, “in case the Council might want to seek a redress in a law court.” The Senior Superintendant of Police, responding to a complaint by the Chairman of the OUCC, also warns the traders that “if Nigerian independence would mean anything, orders by constituted authorities must be obeyed.”

The Onitsha Market Traders Association (OMATA) responds immediately with a press release pointing out that (a) on any weekday during which the Onitsha traders fail to trade they would lose a collective total of about £100,000 worth of business; (b) during an inactive weekday they would have no reliable means of protecting their articles of trade, because they regularly employ only night guards to watch over their stalls; and (c) the OMATA was not informed by the OUCC of its decision, and therefore had no opportunity to help the traders make any new arrangements that might be needed for this unexpected circumstance (watchmen for their stalls, for example). Therefore, the Association resolved not to honor the Council’s order.

This interchange seems significant in several ways. The participating activity which the NCNC-dominated Onitsha Urban Council offered to the traders is defined as “fitting tribute”, whose requisite behavior is purely passive and “self sacrificing”, which only affirms the potency of kingship (without giving the traders any positive identity of their own as a counterpart). Second, the response of the traders is primarily (and individualistically) pragmatic. Third, however, the OMATA draws attention to the implications of the Council’s demand for community relations: the decision was unilateral, and as such foreclosed whatever prospects of cooperation might otherwise have been available. To the Ndi-Igbo traders it may have seemed that the Council was in effect proclaiming “Community or else (punishment)!”

This issue is discussed vehemently for several days during which the Spokesman and the Observer play roles consistent with those we have previously identified, and then it completely vanishes from the news. That it generated such intensity was probably related not only to the fact that nearly all of the Main Market traders are hinterland Igbo men, but also to the political problem perceived by the NCNC — that the leaders of OMATA are known to be not reliably committed to the NCNC camp, but include some potential radicals (linked with Nigeria’s trade union movement), men who are making frequent contacts with the Eastern Observer‘s reporters rather than those of the Spokesman and who therefore might become allied with the Action Group. The NCNC councillors of the OUCC apparently realize, however, that with elections looming ahead and with the OMATA’s already-established reputation for making its own decisions regardless of what the NCNC might try to dictate, their continuing to antagonize the traders in the interests of affirming Inland Town demands for exalting the Obi‘s honor might be unwise.

So this newspaper-publicized culmination of the Obi’s funeral strongly contradicts the ritual’s publicly proclaimed aims. The initial affirmations of civic unity are contravened in the ritual process itself, that is by the absence of active, representative roles being offered for the nearby Ndi-Igbo communities (except for the Aguleri hunters and some other “Riverain Ibo” public involvement in the news media, and — partly — the presence of members of the elite representing diverse nonlocal backgrounds). That the Onitsha Market Amalgamated Traders Association (whose membership comes overwhelmingly from these ndi-Igbo communities) refuses to honor the event in the proposed passive and extremely altruistic way demanded of them is no doubt largely the result of pragmatic motives as they claim, but says something as well about how they regard the directors of the play (and the “community” these agencies appear to be seeking to construct).

On this occasion, the Action Group-sponsored Eastern Observer gains the final public word on the issue, when it pointedly remarks that “the notice ordering the closure of the markets hung loosely on the walls of the Market Superintendant’s Office in the Onitsha Main Market.” The Main Market Superintendent (Mr. Osaka) is not only an NCNC member but also an Onitsha Indigene.

- See our section “Newcomers’ Experiences, Wider Realities”. [↩]

- Note especially the reference to “obedient ‘Boys’ of the Empire”, a sarcastic allusion to African officials awarded the “Order of the British Empire” (O.B.E.) for loyal service to the colonial regime. [↩]

- His office as President of the OUCC has become primarily ceremonial and traditional-affairs-oriented, while that of the Chairman directs the everyday business of the Council. [↩]

- Note that this criterion contradicts a stated precolonial requirement that the Obi should not be seen to speak in a “public” setting. This traditional rule was invoked in 1958 when Obi Okosi II visited Lagos, but various Onitsha people expressed embarrassment to me concerning this (as they openly defined it) subterfuge. The problem of competence here was not that the Obi was illiterate or lacked grasp of English, he was simply inarticulate in situations of public speaking. [↩]

- I Corinthians XV:54. [↩]

- For early historical relations of “Ogbaru” people with Onitsha Indigenes, see Henderson 1972:36, 40 41, 51 52, 65 73. In 1961 John Oduah was also President of the Ogbaru County Council. He had attended the Holy Trinity school at Onitsha and then spent many years in the city, becoming at one time President of the Ogbaru Progressive Union, Onitsha branch, prior to being selected as King of Akili. See the Eastern Observer Nov. 29, 1960. [↩]

- Sad to say, our photograph of this group was irretrievably lost sometime when I was teaching at Yale, where I often presented slide shows of these and other events from Onitsha, and on one occasion I must have inadvertently left the slide in a projector. [↩]

- I declined the opportunity to photograph them. [↩]

- [↩]

- Nigeria magazine Volume 72; see the main Bibliography, Chapter 10 in this website. [↩]

- At that time I was stylistically only a few years away from my hometown of Casper, Wyoming, where my own associates’ styles of dress were expressed largely in jeans and sweat-shirts. In subsequent years I have sensed in some Ndi-Onicha a sensitivity to and skill with dress styles hardly paralleled anywhere. All of this beseaks, of course, degrees of affluence and leisure as well as rather cosmopolitan experience among the participants. [↩]

- And of course no masked being would be allowed to do this. See Henderson 1972:308. [↩]

- This image is drawn from Nzekwu 1959:104 [↩]

- This is a remarkable fact. Okosi II’s father, Samuel (Okosi I), fostered (as a convert to Roman Catholicism) the view that “Eze does not keep Juju”, a formal rejection of previous traditions whereby the royal throne contained various objects of ritual power, from the perspective that such objects were agents of The Devil. Apparently Schiedham’s Schnapps, a product of Christian Europe, avoided this otherwise blanket proscription. BTW, see Van den Bersellaar 2007 for a brilliant discussion of some of the history of this Devil’s Brew. [↩]

- Van den Bersselaar 2007 has published a remarkably thorough history of the significance of Dutch gin in West Africa, showing that, despite the strongly “traditionalist” devotion of West Africans (including Igbo-speaking peoples) to these products, their prominence in rituals arose only in the late 19th century. [↩]

- Van den Besselaar 2007 shows how during the 20th century beer drinking became the main social drink of modernizing classes in Nigeria and other West African countries, a role sought by Dutch gin-sellers but unsuccessfully. [↩]