note: click on the image you want to enlarge.

The strange-looking image at the top of this page illustrates my struggle to understand the Onitsha village of Odoje , or Odojele (Lit., “Place of many palm trees”): it is taken from my 1972 book, The King in Every Man, Figure 13 facing page 98, and reflects an attempt to reconstruct the building of a village out of the “bits and pieces of previous history” (Igor Kopytoff 1987).

For many years I wondered about the organization of this village — how it came to be “what it is” — but never found the time to explore my limited array of fieldnotes in a way that would enable me to make the strongest and clearest estimates of its history and social organization.

Probably this diffidence arose from my experience during my fieldwork. My field assistant Ifekandu Umunna, who was a Daughter’s Child (nwadiani) to one section of Odoje, took me to consult a member of his Mother’s People (ndi-ochie) Akunne Odiari (I hope I remember his title name correctly here). To my deep dismay, Mr. Odiari refused to speak with me, citing the fact that he knew I had been consulting with an Onitsha man he held in deep contempt.

I say “dismay” because as I sat in the room where Ifeka had brought me, I saw an array of Okpulukpu , the carved wooden boxes kept by Ndi-Onicha to remember — and (in 1961 ) continue to serve — specific patrilineal ancestors. This particular room contained so many of these — memory fails, I will just say “dozens” — that I knew I was dealing with a person who controlled some very deep ranges of Onitsha historical knowledge. Elsewhere in Onitsha I had seen substantial collections — half a dozen or so, but this one far exceeded my previous experience (and I would never see anything remotely comparable again).

[Here I add a note to readers: anyone reading this who Knows Something about Odoje, and wishes to inform me further, please do so to my email: rhenders@email.arizona.edu.]

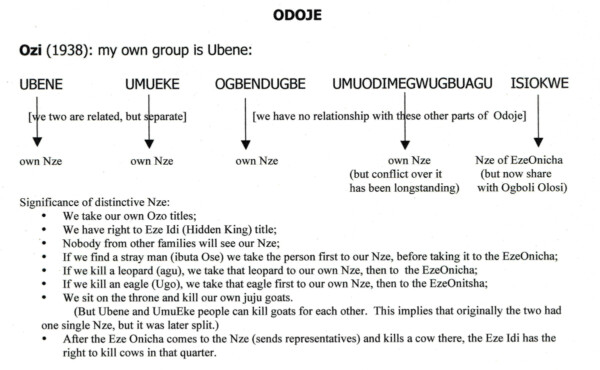

So in part my chagrin follows this historical experience. Here, I have decided simply to present a diagram-summary that I developed after reading through an Onitsha court case brought in 1938 and involving two men of Odoje: Umera, the Ozi of Onitsha, against a fellow chief of Odoje, Mbanefo Odu. 1

In his testimony, the Ozi provided the most detailed and formal outline of the structure of that village that I have ever seen, though I never managed to explore its claims while in the field. (I have added to the diagram a few points of opinion provided to me by Onitsha men in 1960-61.)

Isiokwe of course has its magnified (distinctive) pedigree, as an offspring of senior sons of Eze-Chima, so it’s evident that its Nze derives from that source. ( It’s noteworthy, though, that by 1938 it and Oagboli-Olosi had evolved separate Ozo title sharing in that regard.)

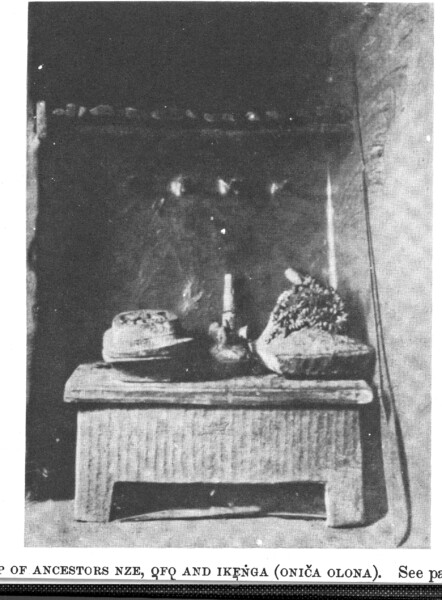

The other four major sub-villages each had its own Nze. This is remarkable; the Nze is a pivotal dimension of cultural self-identification, deriving we may presume from the deep ancestral connections of each of these subdivisions to the ancient Igbo-speaking kingdom of Nri, though many versions of Nze evolved in Igboland west of the River Niger after Nri agents sojourned (and sometimes settled) there (se in this Chapter, “Niger-Benue Worlds”, Nri et al). For example, see here below an Nze complex photographed by the great early Ethnographer of Igbo worlds, Northcote Thomas:

This image poses many questions which cannot be pursued here, but clearly the object at left, is cognate in structure with a feature of the Nze complex found eastward across the Niger in Onitsha. The several different Odoje versions we see indicated in the Ozi‘s account in part probably derive from some of these Western Igbo sources.

These patterns in eacch sub-village are very intereting, since they show that, in essence, each sub-village here — a separate holder of the Eze title — is poetntially a kingdom of its own: that is, each holder of Nze will first display its own “royal” prerogatives within its membership — for example, while taking a killed leopard to the Eze-Onicha indicates an acceptance of the latter’s royalty, the actors first do this same ritual to their own top leadership, thus affirming their own potential to form their own separate kingdom. An option is retained for moving further away from current leadership and establishing their own separate unit. The potential for separation, shifting allegiances, is preserved. A major point here: several of the Nze complexes probably come from towns in Western Igboland (indicating the holders came from those locations).

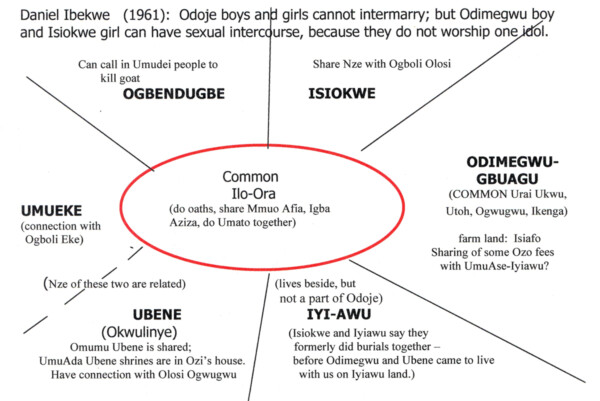

Now: here below is a summary outline given me by Paul Ibekwe of Umu-Odimegwu-gbuagu in 1961. It shows the focus of social unificaiton of Odoje in the Ilo (Village Square), and the activities shared there by the various members.

Note that I have placed Iyi-Awu in this scheme, although in 1960 Iyi-awu people by then were strongly affiliating with Umu-Asele, much less with members of what is now Odoje. Their earlier history suggests fairly recent (nineteenth-century) attachments with another direction (toward Isiokwe), and that Odoje itself as we have seen it in mid-twentieth century may have been recently re-constructed, though it definitely existed in the consciousness of Ndi-Onicha by 1857 when its dominant chief, Nwabufo Ogene (“Wabuvo”in the journals), reportedly led this village in “war” against the fellow Onitsha village of Umu-Dei in a dispute over local land. () See Henderson 1972:366, where “Wabuvo” was said to have stolen “the large drum of Umude”, and had occupied land apparently claimed by the latter, and again where Nwabufo , now having taken the Eze Idi title, thus relinquishing his Ogene title, appeared to declare his autonomy in relation to Onitsha hegemony more strongly. 2

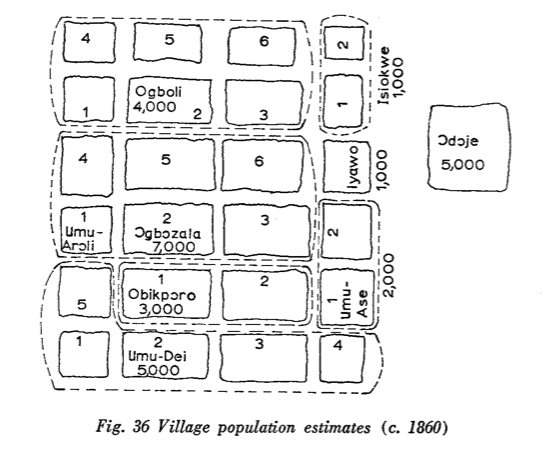

It was also an interesting fact that, when Crowther and Taylor first looked at Onitsha in some detail (1857) and drew a map of the town, they at first missed Odoje entirely. Taylor then provided a corrective map, showing a block marked “Odoje”, located off at some distance from the other villages (all of these shown adjacent to one another, including Isiokwe).

It may help us grasp what has happened over time in this village and village-group by briefly departing the details on the ground and looking much more widely at the long-term history of the broader regions in which Onitsha has long been embedded.

West African History: Oral Traditions and “Identity-affirming Fantasies”

To venture briefly even more widely: In a remarkable recent essay about museums in the Mexican state of Oaxaca, the New York Times’s cultural critic Edward Rothstein3 draws a sharp contrast: On the one hand, in Oaxaca strong historical shadows are cast by the substantial and well-preserved archaeological features that are still present in the landscape of that state (including many large stone buildings, for example), and by local oral traditions and other research resources (which enable serious students to build realistically measurable pictures of the past); on the other hand, in the United States only much blurrier visions are available for research about most Native American cultures, because overall the archaeological record is much less robust and the original populations became drastically decimated or scattered during times of colonial invasion. As a result, museums in the United States today are bent into the task of constructing largely imaginative accounts of the past, “in many cases relying mainly on frayed strands of traumatically disrupted oral traditions”, where cultures have disappeared,

“leaving behind neither oral traditions nor written records. And forced migrations and centuries of warfare so disrupted native traditions that the past now seems little more than an identity-affirming fantasy.”

I cite these comments because the essay rang a bell in my head concerning my own research in West Africa, pursued sporadically from 1960 to the present and focused around historical relationships among Onitsha people (Ndi-Onicha) and their neighbors living in the southern parts of Nigeria. Not that Onitsha people and their neighbors at all “lack oral traditions” or were generally as “traumatically disrupted” as were the lives of most Native Americans in their colonial experience (though centuries of slave trend left a disastrous toll, in many places, and since 1966 the inhabitants of southern Nigeria did fall victims to very serious disruptions), but certainly if we look at recent historical research in Nigeria we can see that to a considerable extent the past has become to some extent (and especially for some of our more politically-active historians) a series of competing “identity-affirming fantasies”.

To some degree of course, all histories contain identity-affirming fantasies, and in this page I propose to explore one particular array of historical self-identifications within the old community of Onitsha, that composing the Onitsha Village of Odoje (or Odo-ojele, “place of plentiful palm trees”). I want to do this through a distinctive analytical lens for African history, developed by the anthropologist Igor Kopytoff and his associates: the notion of the “Internal African Frontier”. 4

Kopytoff on “The Internal African Frontier”

Igor Kopiatoff: most African polities and societies have been constructed out of the bits and pieces (human and cultural) of pre-existing societies.

The “tribal model” arose out of 19th-century self-conscious nations of a new Europe constructing as its forerunner an ancient “tribe” as a uniform “breed”, possessing unity of physique, custom, politic, language, mind, group identity (“ethnicity”, we now call this); this was the embryo of the nation: an ancient charter for nationalism, rooted in common descent/blood/character. It fit the realities of European history poorly, and it fits African societies even less well: in Africa the “tribe” in this sense is a rarity. Its implicit meaning—“an ethnic germ, its beginnings lost in the mists of the past, growing through time, retaining its essential character, and becoming a people…a nation.” ((Note here that the late highly influential scholar of Igbo history, A.E. Afigbo, clearly assumed this mirage of ancient “Igbo nationalism” –(though in his case this obviously entailed a strongly political motivation leading hin to construct his own “folk history”.))

What is the reality that applies best to Africa: many Ethnically ambiguous marginal societies: some are more glaringly so, e.g. “a society.. (that) represents a mishmash of regional cultural traits”, that does not quite hang together, usually small, not much time-depth. Its legitimacy often questioned by polities residing nearby. ” Note how, in miniature, this fits the situation of the Onitsha village of Odoje. (And it also fits the community of “Onicha-mmili” as a whole, clearly constructed out of a variety of “bits and pieces”.

Such a society may construct a unitary “official” history, but it is “belied by the individual histories of its separate kin groups that show their ancestors coming from different areas and at different periods” (refugees from war/famine; losers in succession struggles, etc;); members may maintain relations with relatives from other places, and within the group there may be differences in customs and language. (There may be a dominant “public” language, but also private in-group language forms.) These are societies that have emerged out of a “local frontier”. People become disgruntled and leave, go into the bush or cross a river (the local frontier); this may merely become another village in a group, or an expansion of a metropole, or may become a diaspora (for example, the Hausa, swahilis, Fulani), or on the other hand a new hamlet that grows into a village, etc. We see these in societal mythologies (a “hunter” founds a community), but also in fact.

……………………………………………

Kopytoff elaborates these points in various directions in his work, but the point is clear. For Onitsha, it is notworthy that, at a variety of levels, one finds sub-village or village units whose members recount histories of ancestors (or contemporaries) coming from elsewhere. This is not a fact to be “hidden” (though it sometimes is), but a testimony to the remarkable resilience and creativity of these Sub-Saharan African societies, throughout their histories.

- For an account of the Ozi’s Ancestral House, see Chapter 3, “The ancestral house…”;; for a memory of Mbanefo Oodu’s son, also the Odu, see Chapter 8, “Some Ndi-Onicha Exemplars…”. [↩]

- Ibid.:475-6. Both of these examples were drawn from Crowther & Taylor 1859; see The King in Every Man for these sources. Curiously, Reverend Taylor seems to mis-date his journals as starting in 1856. See “The Gospel…”, page 241, [↩]

- Rothstein 2012 [↩]

- Kopytoff 1978. This writer, one of the outstanding masters of African cultural history, died in 2013. [↩]