(Note: the writing which follows in this chapter is phrased in the present-tense except where otherwise noted. The “ethnographic-present” here is the early 1960s (not “today”, the 21st century time of these writings).

[Note: Click on any image you may want to enlarge.]

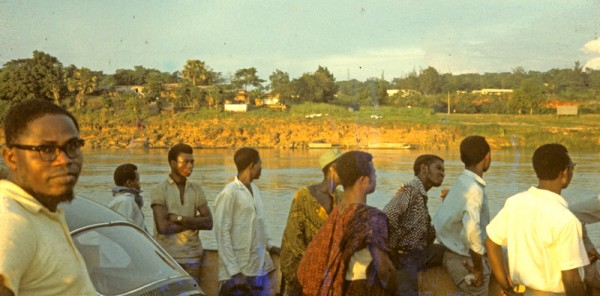

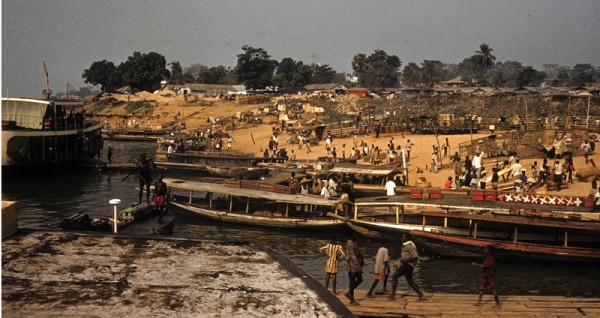

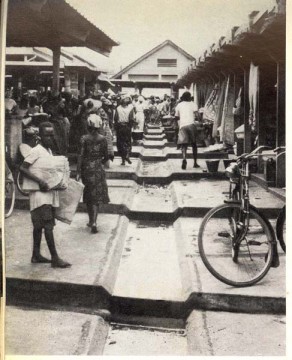

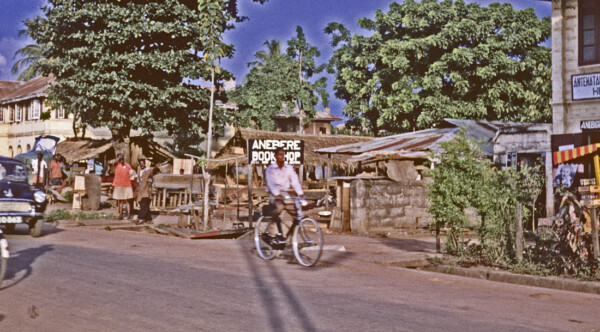

To call a major part of Onitsha “Otu” (“Waterside”) recognizes that this entire space owes its expansive complexity to the ancient link of the uplands (whose people were and are sometimes called Ndi-Ani-Ocha, “People of the White lands”) with Ndi-Olu, “People of the floodplains”. Moving slowly along the river on the massive government ferry, one can see some Ndi-Olu streaking past heading downriver (presumably toward one of the Onitsha marketplaces further south):

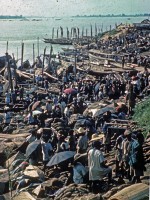

Much of the produce we see moving this way is coming from the Anambra River floodplain directly north of Onitsha, with its extensive plantations of Guinea yam and rice (but much also comes from Northern Nigeria ). Trade of this kind along the Niger can be traced back at least to the 14th century C.E. (and is probably much older).1

Approaching Onitsha, the Government vehicular ferry on which we ride often meets one of a thriving complex of private enterprise passenger ferries (some are called “River Taxis”) centered at Onitsha Waterside, where boats of various dimensions compete for passengers and their relatively small quantities of goods. The government runs two vehicular ferries, each able to carry 50 passengers, 8 lorries, and four cars. (I never photographed either of these Leviathans, though I was riding on one for most of these photos.)

First sighting our destination in late September 1960, we have almost no conception of the human meanings associated with the string of lands lying before us. The history of who owned, and “who owns” the various parts of the grand terrain loosely called “Otu-Onicha” scarcely occurs to us newcomers, yet in the telling of it one faces the fact that the complex questions of land tenure in operation here form an almost Gordian knot historically, still only partially understood. (It will continue to puzzle us later.)

1. Akpaka Forest Preserve to Marina Ferry Landing

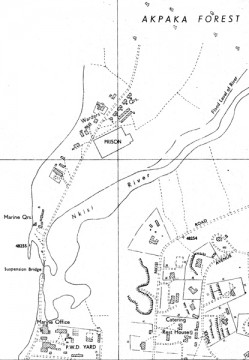

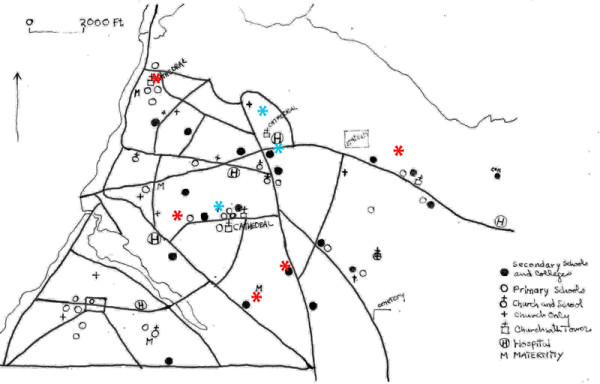

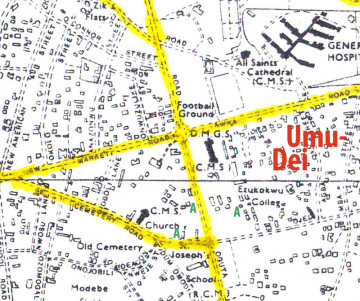

To the right, a map of the northern fringes of the town show where it fades into the rising expanse of the Akpaka Forest Reserve. (This was established as such in 1909, after experimental efforts in growing commercial crops had failed; in the 1960s it still remains a somewhat protected haven for wildlife.) . The map shows the prison location at the southwestern edge of this expanse, and a Leper Settlement was located further north in this vicinity as well in the early 20th century (shown further below).

See also the outlet of the Nkisi Stream, crossed by a suspension bridge, and south of that the Marina Offices and P.W.D (“Public Works Department”) complex. This is where auto-vehicular ferry traffic load and unload in 1960, and where processes of organizing and developing road transport in this area are centered.

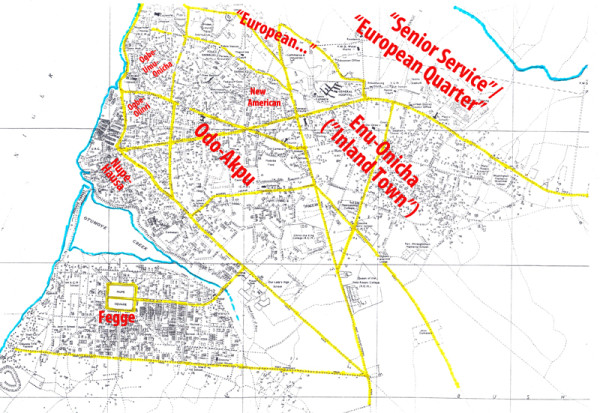

The northern portion of the town visible east of these features remains set aside for official offices and residence, and is in September 1960 still called the “European Quarters”. (We’ll see more of that area further below.)

Readers take note: as we proceed here, you may want to compare these 1960-62 scenes with images we now have dating from 1905-1911. For access to these, go to Chapter One, “A Pastward Look: Robert McWhorter…”.

Below, a view from the southern edge of Akpaka Forest Reserve, looking out toward the southwest where a stretch of newly-cleared land shows preparations for expansion of the old European Quarter, now (in 1960) to be available mainly for housing members of “the new elite” (the term employed by Smythe & Smythe 1960.). The River is just visible beyond a new building complex being laid out at far right-center.

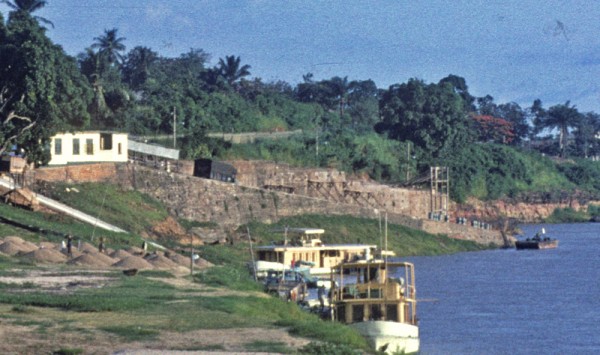

In the image below, some buildings associated with Government stand out near the Riverbank in the foreground as the ferry passes by going south. Well behind them, the strongly incised drainage channel of Nkisi Stream (pre-colonially, Ndi-Onicha‘s primary source for drinking and bathing water) is evident in some shadow at right, running southward to its confluence with the Niger. Nkisi Stream remains the primary source for the city’s drinking water, and is known by some European residents for its sport fishing (though these fish are considered sacred and forbidden to its “owners”, Ndi-Onicha).

Below, the elegant Haulk suspension bridge spanning Nkisi Stream was built by the newly-established Colonial Government early in the 20th century, to link the Onitsha Marina Road with more remote portions of the government preserve. Beyond it downstream the Marine Offices and the Public Works Department (PWD) headquarters are visible. (Photo taken by Peter Brigham in 1963.)

Below, you see more clearly the Marina Landing Ramp, and a zig-zag road above it, leading to and from the Marina office. The two government motor-vehicular ferries dock at this location. Placing cross-River motor traffic here separated it from the dense congestion of the main marketplace further south and brought it close to colonial officials involved in managing road transport (particularly the P.W.D., whose primary task is the building of roadways infrastructure here).

Below, on this rainy day(with the River at full flood stage), pedestrians walk out from and toward the ferry along the zig-zag road, while vehicles are loading:

Below, the Ferry Park where motor vehicles await departure is at this moment largely emptied, all of the lorries having departed leaving only a few small cars. The waiting period for loading can be anxious for those in small vehicles, since when the entry gate is opened here typically the always crowded pack of lorry drivers rev up their motors and jockey like fighters, each seeking prior entry. When we use it in “Motu Machis” (our tiny Fiat 600, whose name and qualities are discussed below), we are generally the last to embark (partly because our unusually short wheel base requires special ramp provisions), but we scarcely appreciate the intensity of competition among the drivers of large vehicles, since only 8 lorries can cross at a time, a bottleneck that severely constrains east-west trade of substantial scale. (The promise of a Trans-Niger bridge is visible in the form of massive pylons in the River further south.)

………………………………………

A note here regarding this part of the Waterside: when the British Government installed its power into Onitsha in 1900, this northern area was its prime initial focus. Below, photographs from 1906-1911: at left, the Public Works Department, already a complex engineering and construction facility; at center, the grand suspension bridge (Onitsha’s Modernistic “Eiffel Tower” for 1910, definitely an Icon for the New Age); below right, the European “Guest House”, a massive building for accommodating this new influx of humanity (variously labelled “Ndi-Ocha“, White Persons, “Ndi-mmuo“, Ghosts, etc., by local inhabitants). This building was gone by 1960.

For more visual details on this early period, see Chapter one, “A Pastward look (Robert McWhirter)”.

………………………………………………

Now note on the map at left for 1957, the location of the Catering Rest House conveniently east from the vehicular Ferry Park. Helen and I stayed there our first few nights in Onitsha in September 1960. Here to the right, you see her enjoying a first cup of tea in front of our room (a reservation very kindly arranged for us by Dr. L. O. Uwechia, our sole Onitsha contact at this time). Note also our brand-new Fiat 600, which we have purchased in Lagos with some of our Ford Foundation money, in preference to a used VW Beetle available there at the time for the same price.

While our initial driving from Lagos to Onitsha is uneventful, we will soon learn to regret the choice of this ill-fated machine (which local children chant loudly out as “Motu-machis” after its resemblance to rectangular boxes of paper-thin metal that contain imported wooden matches). “Motu-machis” will appear elsewhere in this volume, never in sterling light. I should say in fairness that we did drive it around southern Nigeria for nearly two years, though with very considerable difficulties and excessive down-times due to its chronic mechanical failures. We survived with it, for which I suppose we should be thankful. We sold it for about 1/3 of our purchase price several weeks before leaving Onitsha, and its new owner promptly wrecked it completely, somewhere along the road to Enugu (so we heard….).

2. From Roman Catholic Mission to Otu coastal markets

Below, a panoramic view links the Nkisi suspension bridge toward the far left with the Roman Catholic Mission (RCM) Holy Trinity Cathedral at far right:

Below, from the river looking southeastward, the Cathedral is partially obscured behind the many trees, but it provides a major landmark for ferry travelers coming from Asaba. The visual prominence of Holy Trinity here barely reflects its importance as an icon of the Roman Catholic Mission in the history of Onitsha, which began in 1885 when Obi Anazonwu granted French Mission Fathers this substantial block of land

At left, the Basilica as it looks today. (Thanks to the Wikipedia source on the RCM Onitsha for this image.)

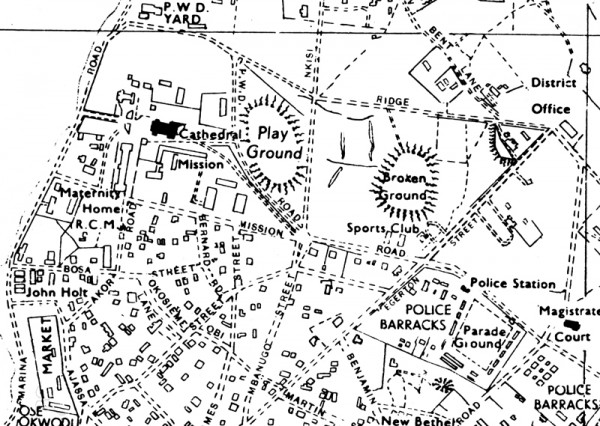

The map below gives a sense of the extent of the lands granted to the RCM in the Waterside, stretching from just below what is now the P.W.D complex eastward to boundaries with official departments in the European Quarter (including the District Office and the Magistrate’s Court) and southward to a boundary with businesses and marketplaces associated with the venerable location of Ose-okwodu :

Below, approaching this portion of Onitsha Waterside, one might (as on this occasion, below) see an array of massive barges standing off from the uplands promontory where the venerable John Holts buildings stand. Beyond these huge machines, the coastline indents toward the east. The Main Market complex is just visible in outline behind the smokestack. (Note also how high the hills stand right beside the River at this point.)

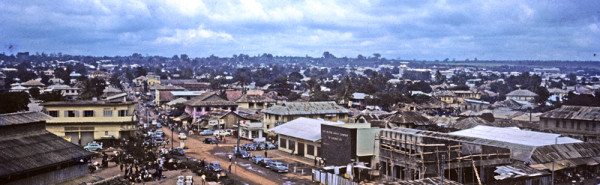

We had a more expansive view below of the Waterside when we first arrived in Onitsha in September 1960, looking toward the southeast at a full span of the River frontage, running from some RCM buildings at far left to the headquarters of the early British merchant John Holt — established in Onitsha around the turn of the 20th Century, this company survives in 1960s Onitsha, conducting an extensive produce trade buying palm oil, palm kernels, and other products and selling imports like textiles and bicycles — on the middle-left promontory, toward the Main Market at center, and onward well downstream to the inchoate Niger River bridgehead structure discernible poking out of the water at far right:

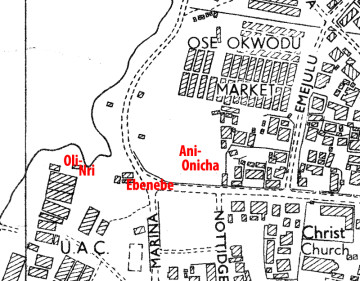

Below, this labeled image shows major divisions of the central coast more clearly. On the promontory at far left, you can see several in a line of John Holt warehouses. Further toward the center south of the promontory lie an array of structures descending toward the River. These include a variety of marketplace types associated with the feature labeled Ose-Okwodu. Behind this complex and rising above it are the multiple arms of the massive Onitsha Main Market (OMM), just completed in the 1950s. At water’s edge are a complex of private-enterprise passenger ferries and cargo boats, marking the location of the ancient (precolonial) riverside marketplace, then labeled Otu-Nkwo2. In the early 1960s it remains a very active place for many kinds of transactions. Toward the right and again on a promontory, the several large whitish warehouses and booms of the United Africa Company are visible.

Below, we look now more closely toward the white array of UAC warehouses and embankment-dominating cranes. Note, first, the large river craft docked beside the cranes. This marks the landing of the Niger Transport and Trading Co. Ltd (NTTC, a subsidiary of U.A.C.). The riverside cliff here provides a crucial deep-water port for river craft coursing the Niger-Benue watershed. In the 1950s and 60s (prior to the construction of Kainji Dam, which radically altered the flow of the Niger) the least depth of the River in the dry season at this point was 8 feet, so river shipping with drafts of 7’6″ could reach Onitsha year-round3

At far right in our iconic image above lies the concrete stairway forming the western base of the OMM, vaguely visible as a sloping surface above a flat blackish line marking cargo boats that come mainly from far north, up the Niger from Onitsha. Note also the clupp of large trees above the slope left of the UAC buildings. This marks the Ani-Onicha (“Mother-earth of Onitsha”), one of three sacred protectors of the ancient central marketplace, one old name of which was Otu-Okwodu, “Trumpet Beach”4 .

Slightly left of center in this image is the location of the ancient Otu-Nkwor, marked here by a slight indentation (an outlet filled here with small boats of various kinds), and toward the far left rises the green Sacred Grove of Ani-Onicha, ancient Mother-Earth guardian, still bristling with her leaves .((In Henderson 1972: 86, 98, 100, 294, 312-313, 502, I described some aspects of the primary religious symbolism that Ndi-Onicha associated with this regionally pivotal marketplace.))

The map to the right focuses attention on the location of this ancient marketplace, which in precolonial times was flanked by several potently protective shrines. The first of these is Ani-Onicha, still preserved and active in the hands of Ndi-Onicha in 1962. The second was Oli-nri, a potent Spirit shrine controlled by the Eze-Onicha, which was demolished when the United Africa Company established its headquarters at its place. The third was Ukwu-ebenebe, “Great Ebenebe (tree)”, a venerable power located right at the market entrance who controlled the aggression of her bees and was administered by Ndi-Onicha women traders. It was destroyed in 1928. ( S.I. Bosah p.28, saying this was done to facilitate widening of the street junction at this point. According to him, the Otu-Nkwor market itself was also called “Afia (market)-ukwu-ebenebe“.). The indentation of the coast at this point (a small drainage outlet) offers some shelter from the direct flow of the River, affording docks for large canoes and very shallow draft ferry vessels.

Note toward the upper center on the map, the multiple rows of metal-roofed sheds, an extended portion of what has been recently called the Ose-Okwuodu marketplace (after an ancient ivory-trumpeter who once announced events there).

The roadway running east-west just south of Ani-Onicha, called “Old Market Road”, was called the “King’s Road” by the 19th-centry CMS missionaries (note the vicinity of their refuge location, labeled “Christ Church”, at lower-right on the map). The entire area around the marketplace was controlled by the Obi-Onicha prior to the death of Obi Anazonwu in 1899. (After that, “everything changed”.)

3. Ani-Onitsha, Lorry Park, Barclays Bank, Ose-Okwuodu

Below left, a view5 looking west into Ani-Onicha shrine, with its characteristic (and substantial) sacred grove (okwu-ani), and immediately adjacent to it, a portion of the main Onitsha Lorry Park. At lower right in the image is a tiny piece of the southern edge of Ose-Okwodu Marketplace. And note the building looming beyond the Park in the distance at middle-left, the office of Errico, the most prominent of the private-enterprise ferry companies serving Niger River passengers here. Below center, the Errico Office overhead sign was missing its initial “E” at the time. Note also the competing, smaller “River Taxi” office left of Errico. This photo was taken from Marina Road. Below right, a customer heads for one of the taxis6.

Below, we now look in an almost northerly direction from a vantage point close to the former location of the Oli-Nri shrine, and across the small inlet clearly shown on the map here toward this part of the “Old Market”. Various markets operate in the open air at this location: unprocessed wood, construction sand, bulk grains, guinea yams, and more. Within the roofed buildings visible toward the upper right, a vast (and to some extent, precolonial) array of commodities are for sale7.

Below, a closer view of the promontory, wharf, and warehouses owned by John Holt. A number of private companies do dredging of the river to provide sand for builders to buy. Many towns in Onitsha’s hinterlands get their sand for building from Onitsha sources.

On a regular basis, this old Waterside location becomes one of the main markets for Guinea-yam distribution to the whole of southern Nigeria. Below, viewing the place now from a higher vantage-point on the east bank, you see a mass of traders dealing with yams and other produce here:

Below, three views of the yam market. Below left, looking north you see an array of produce boats in the background, sporting their riverine sails; the yam market at the fore. At center, a closeup of the massive guinea yams, an historically major foodstuff for this part of Nigeria .8 At right, the market on a relatively inactive day. Big-bulk bags of bulk rice and/or sorghum (“guinea grains”) are visible at mid-photo.

Immediately above, some African “Guinea Yams” (Dioscorea alaate). I cannot pass these images without singing the praise of this foodstuff, which apparently has (unfortunately for them) largely escaped Western palates.

Here view one of the world’s most marvelous foods. Most Africans (certainly, most Igbo-speaking people) preferred to eat them as a thoroughly pounded, amorphous product called “foo-foo”, which they would pull out of a rounded pile with four right-hand curved fingers-full, place the mass in their mouth and swallow it whole. I much preferred having slices of it fried in palm oil (giving it a slightly chewy texture) and served, with ample dollops of the delicious Igbo meat stew which Helen had learned to make from our youthful Nsukka-born cook-steward. A more delicious “meat-and-potato” style meal has never been invented, and is slightly maddening to remember.

Note below, in passing, the broad view of the Anambra floodplain afforded from this vantage point. This vast flat region, part of its southernmost edge visible here as a very hazy flat line running across the middle of the image, from far left to right-central is the source of much of the produce we are viewing here and will see elsewhere. (In 1960, portions of the Anambra forest still provided refuge for the last remaining elephant populations in Nigeria. They were much hunted for their ivories, source of the prized horns associated with Ozo title among Igbo-speaking peoples, and I think they are gone now.).

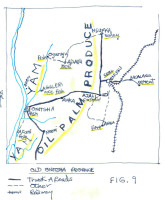

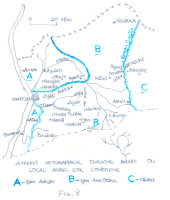

S.O. Oduah, in his urban-geographical study of Onitsha in the late 1950s, presented these maps. which he kindly allowed me to use for my own work

At left, a view of a major economic exchange of yams (and rice, and fish) from the lowlands, for oil palm produce from the uplands. Oduah also noted the categorical divisions among Ndi-Igbo of the same area, drawn by the British officer/ethnographer of the 1930s, M.D.W. Jeffreys, who distinguished between the uplands-dwellers, labeled “Igbo-ana-ocha” (“Igbo of white lands”, i.e. the heavily-populated area subject to severe erosion but where the oil palm predominates) that breaks off toward the east in the escarpment of the “Enugu Cuesta”, as distinguished from “Igbo-adegbe”,, i.e. Igbo of the lowlands, including the lower reaches of the Mamu River where it feeds into the Anambra River. Here in the Onitsha yam market we are seeing part of one major side of this trade.

Below, a closer view of this “Old Market” location shows how the market managers have sought to direct and limit traffic with moveable fences, while behind these “avenues” a closer view reveals local methods of trash disposal: a long, high hillock of accumulated materials (which in our experience was periodically burned, at night).9

Below left, a view of the bulk wood market, and at right a closer perspective, same image. The demand for wood is immense, and firewood in particular is brought into the Onitsha beaches every day, and from whence wide distribution goes far to the east by means of lorries.

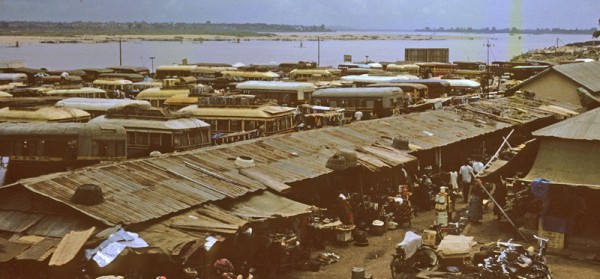

Lorry Parks: Private Enterprise Transport

Returning to the close proximity of Ani-Onicha and the Main Lorry Motor Park in Onitsha, we focus more closely on the lorries themselves, parked en masse, an agglomeration of woodworks and steel machinery reflecting a prime feature of African private enterprise of this time. As Edward Hawkins observed in his landmark study of Nigerian Road Transport10, it was a fact of great importance that this crucial integrator of the growing Nigerian economy fell into African hands. Onitsha lorry owners — entrepreneurs strongly invested in fixed capital goods — were busily building a local basis for industrialization. Nearly all of the vehicles you see here are finished in Nigeria: local businessmen purchase Mercedes-Benz chassis, for which local African carpenters specialize in manufacturing general-purpose wooden bodies. Some of this is done in Otu-Onicha, and Ndi-Onicha were early leaders in establishing locally-owned motor enterprise, but they were quickly swamped by immigrant Ndi-igbo, especially entrepreneurs from the city of Nnewi, who expanded their trading enterprises over much of Nigeria, including motor transport proper, sales of mechanical parts, etc.

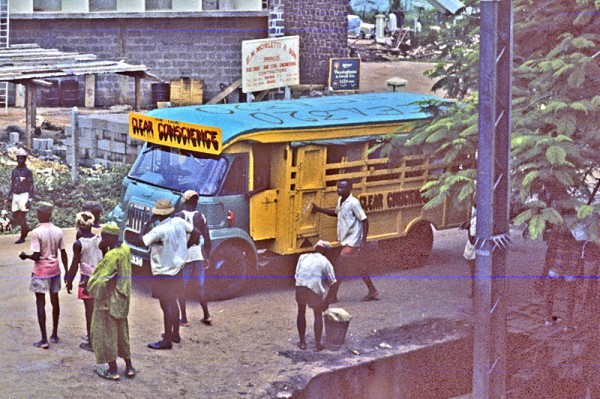

Below, one fine product of the local motor-body construction operation heads away from the lorry park and passes Nottidge Street, up Old Market road in the direction of places east of Onitsha. The newly-constructed, self-consciously-Modern Barclays Bank building stands behind it (filled, during business hours, with multiple waiting-lines of local businessmen holding their cash in trays and boxes, waiting for their chance to make their deposit).11

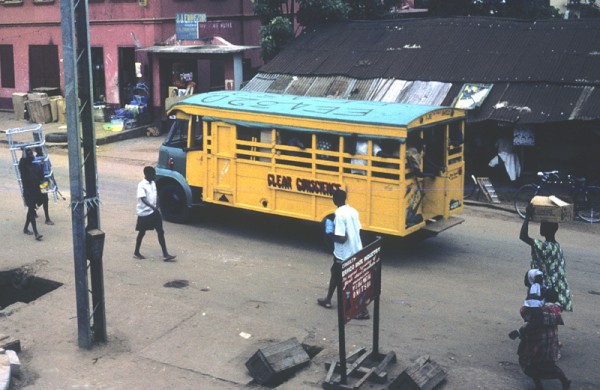

Below, a closer view of this particular lorry shows more details of the wooden body. Note also its iconic label, “Clear Conscience”. Since a pioneering study by Margaret Field in 1960, It has become clear that inscriptions on commercial vehicles of this kind (operating throughout West Africa and beyond) provide fascinating clues to the preoccupations of their drivers and/or owners, as well as specific, identifying labels for others operating in these social fields. One researcher nicely summarized them as “windows through which to view their life-situations”12 My Onitsha favorites in the early 1960s are the one below (“Clear Conscience”), “Tomorrow” (as in “Who Knows…”), and “No Condition is Parmanent”(sic). “Windows into life situations” is an apt metaphor for this kind of identity statement.

Below, a view of this lorry from another angle as it proceeds east up Old Market Road. It appears to contain mainly passengers, but these transports are economically unspecialized — designed for carrying produce at the same time. Wooden seats are removable, and a wide range of passenger/produce ratios is available. Most lorries carry both, to some extent simultaneously.

This profusion of private-enterprise lorry traffic in Onitsha is part of a complex political-economic development that (by the time of our presence in Onitsha) made the Onitsha market system perhaps the largest (and most successful) of its kind in the whole of West Africa, a place where (as one writer put it in 1962), the range of merchandise is so vast that almost anything can be bought there.13 A landmark study of the marketplace conducted in the mid-1960s by J.O.C. Onyemelukwe14 demonstrated how Onitsha attained this impressive central-place prominence. In addition to the underlying geographical factors of its food-deficient, oil-palm-rich hinterland and its riverain connections to other worlds, an ethnic-economic dynamic developed that produced a distinctive kind of credit system among Ndi-Igbo traders, transport owners & drivers, and other crucial role-players operating over long distances, a practice locally called “the way-bill system“.

Below, these images of the Onitsha Main Lorry Park show the machines linking these operators together: the motor lorries that come from afar and the “trucks” (more appropriately called, technically, “hand-trucks”) that move bulk commodities around Onitsha, operated by men called “truck-pushers”.

One of these trucks, note, sports its own identity. All three photos here & below were taken by Peter Brigham in 1963. These were done on a Sunday, hence many fewer lorries (and stacked-up “trucks”).

The Way-bill System worked at this time roughly as follows. A trader would have a partner (not usually in the formal-legal sense of that term) in a particular distant source center, with whom he agreed to transact business via “way-bills” that were passed through established lorry transporters (owners/drivers). A transporter coming to Onitsha would keep record-books of consignments, checked by the driver as goods were off-loaded, and he would then send a way-bill letter to the consignee via a truck-pusher who worked for him. The consignee (say a Main-Market stall-holder) would confirm the order through the truck-pusher and await delivery of the goods, then later in the day the driver or an assistant would go round to all consignees to collect charges outstanding. A large amount of credit was involved in this process: as Onyemelukwe observed15,

“In pre-war Onitsha market trade capital in both money and stock was very frequently borrowed interest-free and without formal documentation . Traders transmitted substantial sums of money through lorry drivers and fellow traders without the slightest precautionary measures either by receipting or by the formal witnessing of a third party. And it was apparent that trade business in that market was succeeding partly because of, rather than in spite of, the pervading spirit of trust and the practice of non- legal sanctions.”

A Lower Level: “Truck-Pushers”

Above, truck-pushers pursue their heavy work, at left moving up Old Market Road as a lorry passes by. At center, one conveys a substantial load of yams down Bright Street,from the Main Market toward the Lorry Park16). (The image at right gives a closer view of his valuable burden.)

Truck-pushing is a very low-prestige (and low-paying) job in Onitsha, and truck-pushers in the early 1960s typically do not like to be photographed. But they play crucial roles in this system, which makes distance trade so efficient that Onitsha products are not only more varied but also cheaper than elsewhere (including much nearer their source). Looking back, Onyemelukwe attributed this to

the factor of ethnic particularism in the trade business. The traders who interacted between Onitsha market and most of the northern centres and Lagos were almost invariably of the same ethnic (Ibo) origin. So were the drivers operating between them and serving as their transporters as well as their unofficial trustees in frequent money transfers. This was probably because of higher degree of mutual confidence and of common belief in certain social sanctions between Ibos than between Ibos and non-Ibos.

Ethnic Particularism” Thrives in Onitsha

Ethnic Particularism” Thrives in Onitsha

The newspaper clipping at left gives a list of meetings scheduled to be held in Onitsha (The Nigerian Spokesman, July 7, 1962.) Note first the various schedules in this clipping involving an array of Ndi-Igbo “Improvement Unions”: The Ibuokpala Progressive Union, Onitsha Branch; the Umuawulu Progressive Union, ditto; the Ojoto Youth Association; The Enugu-Ukwu Patriorit Union; and so on. Most of these are organizations of people from various Ndi-Igbo towns, who have come to Onitsha to “better themselves” (as it is often put), and these organizations help to mobilize the kinds of mutual cooperation and trust which found another outlet in the “Way-Bill System”. These immigrants to Onitsha built (and continue to build) many social forms to buttress what Onyemelukwe calls an economy stoked with “ethnic particularism”.

Second, observe that the topmost notification in the press clipping is for The Nigerian Motor Workers Union, to be held at “St. Augustine’s Commercial College” on Amobi Street, in the Modebe Layout — a new residential space begun in the 1930s and thereafter strongly populated by Ndi-Igbo immigrants from Nnewi town, and also from Obosi, some of whom have become very prominent in the transport business. (The commercial college connection is significant: the road transport system we have just outlined requires literacy, and schools designed to provide dimensions of this skill blossomed all over Otu by the early 1960s.) At right, note the unpretentious office of the Union, located on Old Market Road and sharing its building with a printing business (this one a considerable producer of the Onitsha market literature I consider elsewhere).

At this point I think it wise to insert a research comment. In 2022 I received a message from Mr. Frank Osodi, a man of Yoruba descent who observed that the building at left in this image (a view along Bright Street in Onitsha, a location close to the Main Market) was occupied at the time the photograph was taken by members if his family. (The Ososi “upstairs” is at upper left in this image.)

This was a remarkable piece of information for me, because I distinctly remembered having visited a Mr. Oshodi along Bright Street during the early part of our stay at Onitsha. I was taken there in part to show that Onitsha included people of both ethnic diversity and considerable social prominence. The Osodi fmily arrived in Onitsha in the late 1800s, established themselves there as traders in gold, and some of them married local women, so they were well integrated into local society (with a street named after them when the Waterside s was formally laid out with named streets in the 1920s).

Unfortunately, I was unable to follow up this initial contact.. The fact was that Helen and I were overwhelmed with the complexity of this community, and — as the reader can see by glancing at ,the newspaper clip presented above — there were so many possible avenues of research that our observations of Onitsha economic activitty inevitably remained extremely sketchy. I did learn from Mr. Oshodi that his family remained in Onitsha during the Civil War that began in 1967, until they were forced to depart when the Federal Government invaded Onitsha and laid waste to much of it. The Oshodis lost everything there. Many hanks to him for this report, which gives me a glimpse of what I missed by failing to folow up this contact.

4. Onitsha Main Market

At right, see a detail from a 1932 map of Onitsha Town, showing the location of the Main Market at that time (which even then was widely known as a great West-African marketplace). The slightly diagonal slash-marks at image center show the distribution of Main Market stalls, just south of the northern premises of the United Africa Company (UAC). The circled numbers denote street names; no. 14, Johnson Street, cuts through the marketplace roughly north to south. No. 1 refers to New Market Road, another major marker-street running across the map here E-W on the south side.

This marketplace, whose predecessor, traditionally called Otu Nkwor (“Waterside or “beach” + Nkwor-day), Nkwor being the fourth and final day of the week in Onitsha dialect of Igbo, was as we have seen located throughout the 19th century further north along the beach beyond the top of this map, but after the establishment of European authority and the subsequent expansion of trade (and political problems and conflicts) the British authorities decided to move it in 1916-17 to the place flanked on both north and south by lands held by the United Africa Company (U.A.C.), within which its dynamism could hopefully be better contained. There it gradually grew through the first half of the twentieth century into a very large marketplace, some said the largest in all of West Africa.

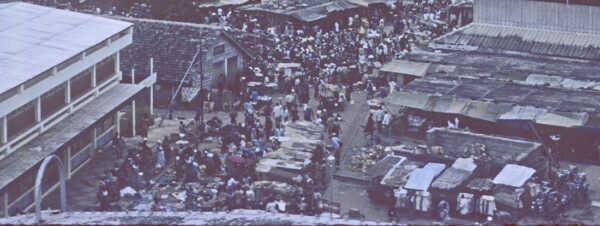

Prior to reconstruction of the Market in the 1950s, canoes landed on a muddy beach and traders had to make their way upward through dirt (and often muddy) slopes. Otu Nkwor buildings were situated on bare ground and were made mainly of corrugated iron sheets and roofed with palm mats. As the marketplace grew it became increasingly crowded and lacked organization, but nevertheless attracted expanding numbers of traders from far to the north and south along the river and from all of the towns and villages of the eastern (and to a lesser extent, western) uplands as well.

Volume 65 of Nigeria Magazine (1960), published an illustrated study of “West Africa’s Largest Market”, under the Assistant Editorship of Onuora Nzekwu (a major Onye-Onicha writer, who supervised the study) which included images from the Old Marketplace:

Note the fiber-matted roofing on the buildings in these pictures, which provided ready tinder for frequent and sometimes highly destructive fires. Note also the crowding and apparent disorganization. As Nzekwu points out, “In the old market everyone sold a variety of things and people had to travel the whole market, bargaining hard in order to buy a few things…. The Market presented a picture of such confusion as gave the impression that no serious business could ever be conducted there” (p. 137). 17

Partly because of the tendencies in this marketplace toward social, economic, and even medical chaos, in 1949 the Onitsha Native Authority (led by Ndi-Onicha indigenes) began a project of organizing market reconstruction, which (after much political struggle) met with approval by the Eastern Nigerian Government in 1952. In 1956 actual construction began.

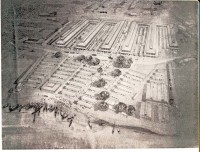

At right, an architect’s vision of Onitsha Main Market, reconfigured as a modern entity in 1952 (and roughly foreseeing its eventual shape): toward the top, two massive east-west-oriented, E-shaped buildings with three levels of open-air windows below sloped roofs, the whole floored with concrete. Lower down and sloping toward the river, 45 low “I”-shaped buildings (each divided into two separate sides), low and flat-roofed, arrayed in a series of terraces sloping downward to riverbank stairway, all likewise floored with concrete. The whole marketplace would contain more than 3,000 stalls, as well as a slaughterhouse, eating houses, engine rooms, water tank and administrative building18.

At right, a view across the central structures of the Main Market in 1962 (here photographed in from the top of the market’s 100,000-gallon water tower, located on the southern edge of the 15-acre complex. The hills visible toward the north beyond the market roofs contain at this time mainly portions of the European Quarter.) Note how the three-tiered roofing, each with open-air windows, can both provide strong-flowing cross-ventilation for the inside yet also full protection from inclement weather.

At right, the portion of the 1957 map (cited above) centering around the Main Market shows it near the middle of the image.

During our very brief surveys of the Main Market in 1961-2, we did not photograph inside these buildings. Here we rely mainly on our Nigeria Magazine source19 for a view of the interior.

(From the same source), one of the “Hotel” areas (providing food services):

As can bee seen below, a full third of the “E”-shaped roofed marketplaces are devoted to cloth sales, clothing sales, and tailoring.

At right, a substantial stall in the cloth-dealers’ portion of the Main Market.20

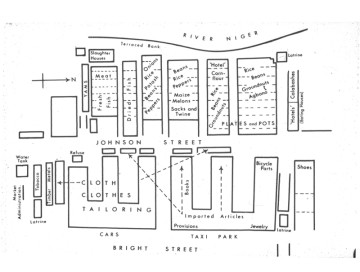

Below right, a diagram of marketplace organization21.

On this map, Bright Street marks the endpoint of vehicular traffic, which runs one-way (from New Market Road left, toward Old Market Road to the right). Johnson Street bisects the Main Market and is reserved mainly for foot traffic.

Returning to our previous water-tower views of the market area in 1962, below, looking now west of the E-shaped towers, we see the array of some 50 I-shaped, low and flat-roofed concrete structures containing the main portion of the Produce Market. Beyond these upstream, the U.A.C. warehouses stand beside their cranes where the largest Onitsha docks are located.

Note again how the Anambra River floodplain stretches across the entire central horizon. At far lower left, the retail store of G.B. Olivant (see also further below).

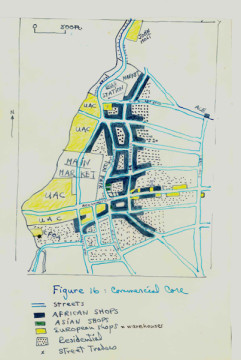

Below, a view from the same elevated location, now looking toward the east-northeast. The visible buildings immediately beyond the E-buildings toward center-photograph were a prime portion of the town’s commercial core, owned mostly by African businessmen, except for the French-owned S.C.O.A. (the yellow building at middle right).

In the late 1950’s, S.O. Oduah’s Urban Geography study of Onitsha provided a mapping (at right) of what he considered the core. The upper stories of many of these commercial buildings, and the central part of the city blocks they fronted, provided residential quarters for many traders. This core extended beyond what is shown here; Venn Road (the street running vertically at far right on the map) was loaded with commercial activities.

Beyond this area lay the “New American Quarters”, a residential portion of the city built up in the 1930s. Beyond that (referring again to the photograph above) a horizontal line of light-colored structures indicates the continuation of the European Quarters, extending toward the horizon, where the Anglican Cathedral (with its associated Church Missionary Society buildings) is barely visible as a dark elevated rectangle at horizon-mid-right. (We’ll return to this wider view later below.)

Produce Market Overview:

Below, the naked canoe masts just visible near left-center of this image point to the Main Market stair steps (out of sight from this viewpoint). The Produce Market buildings occupy the center of the image. Running diagonally from bottom center toward the upper right is Johnson Street, which separates the Produce Market from the E-buildings.

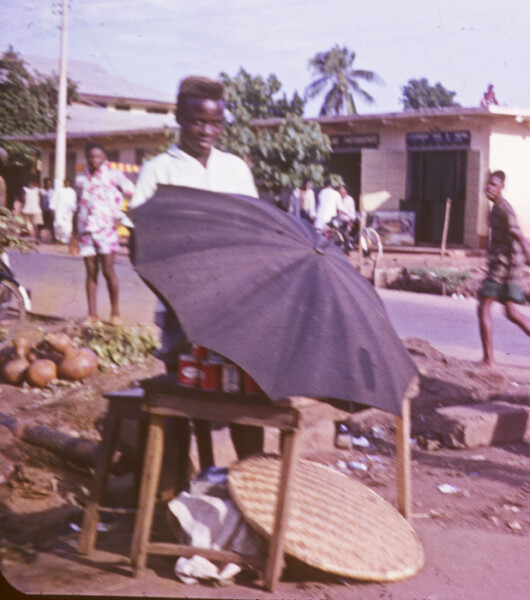

Trinket-hawkers with Bicycle-wheel carts:

Above, , looking from the south end of Johnson Street toward the Produce Market. At lower right, workmen are carrying bags of grain out of the market. Meanwhile, note the long line of street-hawkers’ carts which fill the street in front of G.B. Olivant’s large store (a subsidiary of UAC). Their owners negotiate with the store to buy trinkets, which the hawkers will then roll out on the streets at various locations around the town. These street-hawkers can be found from Johnson Street where goods were taken on consignment from UAC middlemen, then over much of 1962 Otu-Onicha. Below, my research assistant (the late) Ifekandu Umunna (who assisted, along with Michael Agbakoba, our brief surveys of indigenous Waterside businesses) examines the wares of one of these hawkers on upper New Market Road. The vehicle itself is built in Onitsha Town of local materials (except for its imported bicycle wheels).

From grains to fish of all stripes:

Below, Johnson Street approaching the Produce Market becomes quite congested, with market-women selling small quantities of grain wherever they can find the room to be seated.

Below, standing at the level of the street fronting the E-buildings and looking down the terraced (and gutter-drained) stairway of one of six Produce Market avenues leading off Johnson Street, retail traders (mostly women) hawk various kinds of vegetables and fish, displayed along the way, while bulk traders (mostly men) work out of weather-sheltered stalls on either side.

At right, a view from near the bottom of the terraced-steps that shows one of the major improvements of the new Produce Market over its predecessor: the architect-designed concrete flooring that provides not only secure footage but also reliable drainage and therefore relative cleanliness. Onitsha receives nearly 80 inches of rain per annum, and well-managed drainage is very important here.

Below is a portion of the grain market, again with bulk dealers located in the stalls on each side of the avenue, while retail traders lay grains out on the walkways to dry in the sun.

This emphasis on drying out the grains was apparently an important aspect of these market women working with small quantities out under the sun. This was definitely an effort to retard spoilage:

At right, a grain wholesale worker under the sheltering roofs with some of his wares.22 Much of the retail trading of grain occurs toward the top of the terraces near Johnson Street, as shown here.

The fish market area is centered mainly down near the river steps. Below, women sell smoke-dried fish (from the Niger River and its tributaries and distributaries) along one of the avenues. Dried and salted fish (“stockfish”) imported from northern European countries (and quite popular in Onitsha) is also sold in the stalls.

At right, an Onye-Ala (“Mad Person”) wanders along a fish market avenue, readily identifiable as such here by her semi-nakedness (a view never seen in 1960s Onitsha public life except when displayed by persons labeled “insane”).

In his short story “The Madman”23, Chinua Achebe tells a tale of a prominent village man (well-off and aspiring to attain the prestigious Ozo title in his hometown) who so lost his cool when his clothing was stolen while he bathed in a stream, that while naked he chased the thief into a crowded market place, and thereby became for a time defined a “madman”, stained by that change forever, no longer eligible for the coveted title. This moral dualism seems definitive (in our experience in 1960s Onitsha), but we find Onitsha citizens in general remarkably tolerant of and helpful to these unfortunate people. This woman, for example, is free to wander the marketplace and elsewhere in Onitsha mostly undisturbed, and the tin can she carries here, one of her few possessions and her only container for food and drink, is regularly filled with nourishing foods and liquids by local traders and passersby. Ndi-Ala are not bothered in Onitsha unless they become excessively intrusive, as did one named Ajasco (“Man must Whack”), who, after occupying Onitsha’s sole public telephone booth near the Post Office undisturbed for some time, finally crossed the line when he entered a grammar school brandishing a machete and accosting others.

Canoes and ships come from near and far:

Below, a reminder that Ndi-Olu bringing their produce to its primary marketplace typically have many stairs to climb (especially in the dry season when the Niger River is low). But very happily, these stairs are made of solid concrete rather than (as before the mid-1950s) mud-slippery slopes (which must have been very difficult to climb during the rainy season)..

As Jennings and Oduah24 observed, the kinds and sizes of canoes riding the river are many, but the most massive ones, usually covered with mats as you see here, are called “Hausa canoes”, though their sources are ethnically diverse. Ijaw people from the lower delta also run large roofed canoes bringing sugar cane and structural canes, fish, plantains, and mats, and also sell their carved canoes. The Hausa canoes bring dried fish, groundnuts, onions, rice, guinea corn, millet, locust beans and earthen cooking pots. Both these groups often use their canoes for working, eating, and sleeping while they are “abroad”. (Note the vertical poles, which hoist sails to speed travel when the winds are right.)

Interestingly, Onitsha Waterside showed no inclination to develop any approximation to a canoe-building or -repairing enterprise of any kind. This has all evolved entirely elsewhere, though Riverain groups settled in Onitsha at earlier times and played quite important roles here well into colonial times .

The UAC wharf looming behind this canoe landing provides loading and unloading platforms for river steamers dealing with UAC. Here very large-bulk goods may be transferred. In flood season substantial barges can proceed to ports further upstream in Northern Nigeria, as you see here below , a very large craft entirely bypassing Onitsha:

Johnson Street

Moving now beyond the Produce Market and northward along Johnson street, we pass stalls selling a variety of things:

And note here at left the remarkable poise of this Onitsha woman trader, who not only supports a massive tower of goods on her head, but carries a sizeable baby, wrapped securely at her back. The poise and — please do notice! — the aesthetic styles of these hard-working women are marvels to behold.

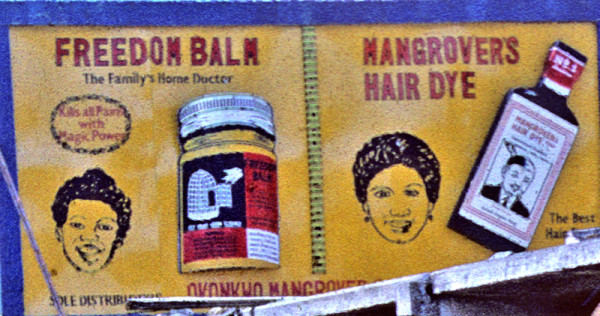

Note at upper right, a (locally-produced) sign advertising locally-manufactured and distributed products:

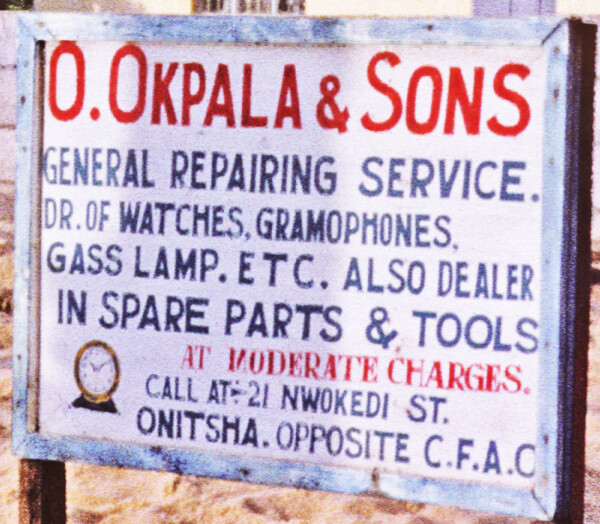

Mangrover’s is one of a number of African-owned manufacturers located in Onitsha, advertising its products widely around town. In turn, Onitsha streets boast a variety of artistic and sign-producing enterprises, one output of which we see closer to Old Market Road:

Moving Through “The Roundabout”

At left, the map shows how traffic approaches the Main Market complex: the route is one-way, and, (though the traffic kiosk visible in the image at right is seldom occupied), the mass of pedestrians on the scene will chant a quick vocal correction to any careless car driver who miss-directs: he will hear a concerted voice saying “One-way! One-Way! One-Way!”

Viewing the entryway at left from the Bida Road connection (which is not one-way), the S.C.O.A. French import company building at far right dominates the inner pivot of the curve. We will make brief comments about these large European-owned entities shortly (but the economics of the Onitsha marketplace arein 1961 in the hands of a Northwestern University Economic Anthropologist, Margaret Katzin, so our steps into this domain are few .((See Katzin’s 1964 article in the Bibliography.))

Viewing the market buildings from the S.C.O.A. storefront, we usually see busy traffic. Typically, printed literatures of various kinds lie spread out along the street edge here. These items include non-local newspapers, magazines, almanacs, and political pamphlets, mainly communist in orientation. We failed to attend more carefully to these materials, but perhaps their location here reflects partly convenience of access and partly official unwillingness to allow them in-house distributions.

At left, the approaching market woman walks along the beginning of Bright Street (which terminates at the junction with Old Market Road, Ani-Onicha and Barclays Bank). Behind her, various vehicles load and unload their goods. At right, a closer view of the frontage highlights a bicycle emporium .

Bicycles are a major means of transportation in Onitsha (and bicycle wheels are used to form various kinds of carts). Motorcycles are also sold and repaired here, though they are not yet popular, while the strongest means of enterprise for local transport is the Morris Minor (shown at left), one of the best small cars available in 1960 and the most popular choice for Onitsha taxi drivers.

Morris Minors are everywhere in Onitsha. Anyone with the money to buy one can open a taxi service, and we see these out at all hours. This is an important source of occupation for local young men, and judging by their driving skills almost no driver-training is needed.

If you look at our street scene photos in this page, density of car traffic looks low, but when we first arrive I find it terrifying because the drivers seem inclined to do anything — speeding up a narrow street in reverse, apparently without bothering to look backward, is a common stunt. Riding the shift-clutch until it begins to burn may often be observed when traffic is stalled for any reason. Drivers also boast of their skills in obtaining ritual sacrifice by running over one of the many chickens that stray onto every street or road. Still, this along with bicycle riding is a major means of moving around the city quickly and effortlessly and is a significant means of jobs and profit.

Indeed, the custom has arisen that people of means should not bother driving themselves but should hire drivers and preferably sit in the rear seat of their vehicle. Women-driving in particular is regarded as shameful, and even I am admonished that I should hire a driver (a suggestion I find absurd for two reasons: having a driver for tiny, Motu-Machis would be utterly embarrassing, and even if I had a Jaguar as some of our local onye-onicha acquaintances do, I would not trust any motorcar to a likely-quite-incompetent substitute. Nearly all these drivers are Ndi-Igbo young men living in Otu.

Below, a view of Old Market Road showing the three most common means of human transport in Onitsha: walking, bicycling, and motor car (with the ubiquitous Morris Minor making its way at lower right). New vehicles from elsewhere than England are also appearing: the sign advertising “UTC Motors Sales” on the blue building at left indicates they deal in Opel, Pontiac, Oldsmobile, and GMC (car insurance is also listed), and some of these new types are visible in the parking lot. (More substantial services are offered further east along Awka Road.)

In fact, by 1060 the new rage for wealthy car owners in Onitsha (especially among Ndi-Onicha) is the 1960 Chevrolet Impala with its prominent, horizontal-running fins, especially in convertible style. Below, we see (barely) this type of vehicle (which may however be a Pontiac) nearly obscured by the Enu-Onicha crowd celebrating the royal rites being performed by Igwe Enwezor in November of 1961, as he bestows holy white clay powder (nzu) among his supporters near the ancient Sacred Grove of the Kings. The car is on loan from one of his wealthy supporters; its hired driver almost obscured by the falling powder. (Traditionally, the new Obi would be carried home from this particular shrine visitation on the shoulders of his men, but this candidate’s supporters feel that a shiny new convertible is more fit to convey him.)

In another direction, utterly practical: the two sharply-contrasting goods-conveyers move along Old Market Road. The lorries vary widely in mechanical quality. Here on the up-hill stretch heading away from the Motor Park, they have little difficulty, but I once watch a machine very much like the one at left above, laboring uphill, begin to expel bits and pieces of its brake system out from its wheelwell on to the road where I stand. To the present vehicle’s right, two truckpushers struggle to control a very heavy load of what I’m guessing to be construction sand. Truckpushers hated being photographed (the job being considered the lowest of the low in Onitsha — only suitable for “bush-men” ), but I surely sympathized with these two overloaded workers, who were doing the essential job of delivering broken-down massive quantities of stuff into locally-deliverable units.

Marketplace-bracketing Foreign Companies

At middle left-central in the image at left, the new UAC Headquarters building looms above the lower end of New Market road. while at right the much older Kingsway store sits directly south of the complex. A still-newer building, called “Niger House”, stands nearby (below).

We largely avoid these shopping centers, but early in our stay we think we might acquire a kerosene stove to augment our cooking facilities at 24 Mba Road, so we visit the Kingsway building intending to shop. We are stunned by the reception given us by the Kingsway “help”: not only do they refuse to engage our inquiries about their products, they begin insulting us as “Colonialists”. Several workers (all African) are present, but none seem inclined to engage us as “customers”. Bewildered, we depart. (Subsequently, our “small boy” Michael Okolo provides us with plentiful wood for our kitchen stove, which serves us beautifully during aoo of our days in Onitsha.)

Otherwise, we avoid these establishments, the economics and ethics of which are clearly beyond our competence, but we do receive one report through Byron Maduegbuna which makes us wonder what kinds of organizations are operating in these big firms. (Margaret Katzin, the economic anthropologist who arrived in Onitsha around the same time as we does not address the operation of these groups, confining herself to local African-owned enterprises. We will comment on her works below.)

Byron’s Report, March 2, 1961 (See our page on “Byron Maduegbuna, a Native Anthropolost” elsewhere in this Chapter.)

Byron’s “boy” Michael was fired from his job at G.B. Ollivant — they called it “retrenched”. Later, Byron worked through an acquaintance of his who was employed there to get him re-hired. But then Michael was told that the staff manager in Port Harcourt wanted £ 35, which would be systematically divided by everyone involved. Michael’s fellow workers asked him why he had never inquired what has happened, that they would have told him what was needed to get permanent employment: he must “pay up”.

So Byron and Michael put together 20 of the £ 35 needed, with the promise to pay the remainder by the end of June. The salary of the young man is £ 12 per month. But now he has become permanent in the company: he cannot be retrenched or arbitrarily fired. (and he might receive soe portion of monies Paid up” by later newcomers).

How did they get the money, I ask. Through the Isusu organization25. Onitsha Inland Town traders like Mrs. Araka invest their money in these organizations in order to get a return. Byron’s mother belongs to one, but she could not get the money from hers now because one member is currently in financial straights. So she referred Byron to another woman, who gave the money at a “high interest rate” (I didn’t learn what it was).

According to another man who is attending the conversation (A highly-respected local shopkeeper from Sardinia), the bribery to obtain and then retain, jobs, is neither limited to men nor to these big companies, though (he says) “the big companies are corrupt from the European top to the bottom. Girls cannot get a job in any of these companies without giving themselves to at least one manager, and often becoming permanent or avoiding getting fired requires “paying up” sexually. One man (a manager of Niger Chemists Inc.) is notorious for this (he lived below the Sardianian for some time): he hires and fires by current sexual preference.

This is likely also true, he says, for teachers, especially in the primary schools. Married women just have to pay a bribe.

…………………………………….

5. Diverse Enterprises Strive

Another set of views from the Water Tower begins here below, first with a brief glance eastward and looking down at the west end of New Market Road (where traffic turns in front of the yellow building owned by the French S.C.O.A. import-export company), while the road that proceeds toward the River is called “Kingsway Road” (named after that department-store “Chemist” arm of the UAC in Nigeria). Most of the large buildings here at the near right are European-owned. Before moving on, note immediately behind these buildings an expansive spread of very dark-hued trees. This roughly marks the residential area called Odo-Akpu (a name denoting an area full of cassava farms), which by 1960 has become a major (largely residential) center of Ni-Igbo social life, including prominently people from the nearby towns of Nnewi and Obosi, which we will discuss further below).

Below, the view from ground level looking uphill along New Market Road. The building of the French firm SCOA is the yellow one at left. (New Market Road is One-way all along here.)

Note, before we tour these commercial streets, the Mobil Oil sign. Three big oil companies are operating in 1960-62 Onitsha: Shell, Total, and Mobil. According to Oduah, each of these has three storage tanks of 600,000 imperial gallons, from each of which road-tank wagons draw fuel to distribute to the company’s agents, who then distribute fuel as far as Ubulu-ukwu in the Western Region and to Awka, Enugu, Nsukka and Ihiala in the East. Smaller dealers use simple hand pumps and may be found in all the new motor stations.

Below, a long view of New Market Road at the lower end, where foreign firms (for example, Bank of West Africa) still appear. As we move uphill, companies are entirely African-owned.

At several locations in Onitsha, we encounter extremely massive “houses”, built in the early 1900s and associatied with early Court Clerks who amassed sufficient wealth to construct them. This example toward riigh- image was one such building , following the pattern of a downstairs circumscribing archway and upstairs living quarters. This is the largest one I saw, but I neglected to identify its builder.

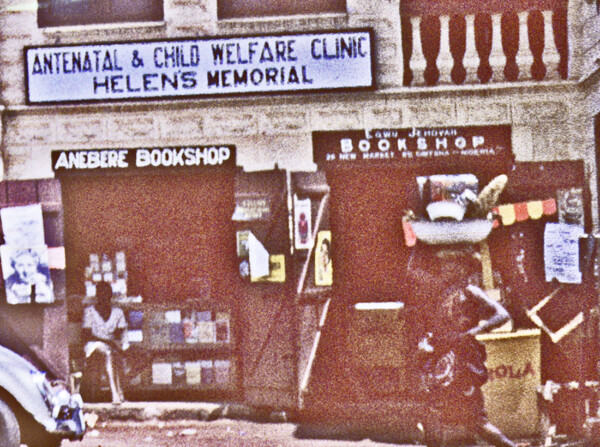

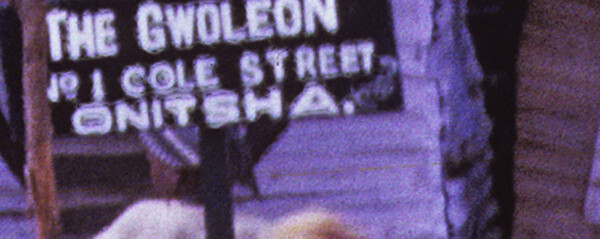

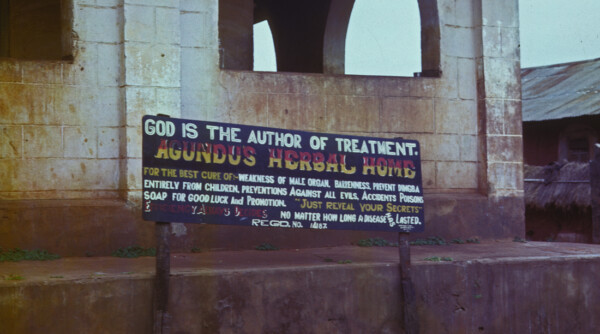

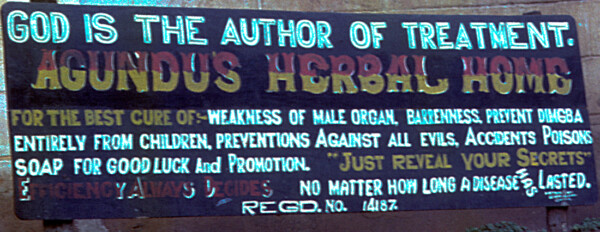

It’s worth noting here at the outset that these streets have a long and rather opportunistic history regarding ownership of properties and the kinds of activities that occur on them. Here at left you see a very presumptuous business (in terms of the signage) side by side with a vastly more humble “Hall of Jehovah’s Witnesses.” This is a pretty striking juxtaposition, but not too uncommon along these streets.

The image above does not convey the contrast well enough. Here is a closer view of the structure apparently associated with the Hall.

Because we have chosen to concentrate our research on the “Inland Town” (Enu-Onicha) rather than the “Waterside” (Otu), we can provide only briefest sketches of the diverse kinds of African-owned and -operated businesses that have sprung up to serve needs of this populace and its organizations.

We encounter very mixed operations at any particular location. For example:

At left, a collection of framed bedsprings. (I did not inquire whether these are locally made or imported., but I would guess Awka craftsmen.) At right, a large pile of builder’s sands for sale. And the associated sign designates a third business at this location:

This designates a genuinely multi-purpose operation., located in the shed at above far left background.

“Engineering” Foci: A vast array of varied products:

We can refer again to some maps drawn by S.O. Oduah in his Onitsha urban geography studies, which may provide some help in grasping the extremely wide spread of various kinds of businesses. So example, his sketch of “Engineering” technology

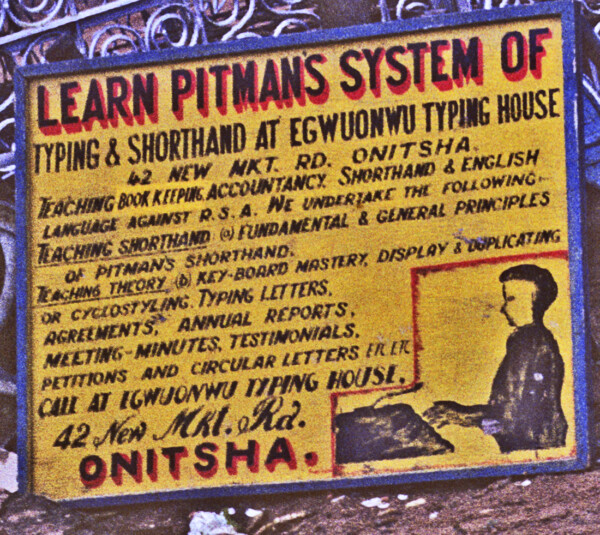

At left,see his map of the distribution in Onitsha of what he labels “E” for “Engineering” , including automobile, motorcycle, bicycle (moslty parts), radio, and clock sales and repair shops, and “P” for printing and typing shops. This array includes a huge range of shops in terms of focus, size and quality, but immediately striking are the sheer numbers of locally-owned shops that he counts for the “Engineering” types.

This impresses me when I drive through the areas indicated, and their scatter suggests many have sprung up as very local opportunities appear.

The map above also shows locations along Awka Road of the two substantial large foreign engineering firms: UAC Motors, and Armel’s Transport (This latter is a firm I come to know briefly, bringing my “Motu-Machis” Fiat 600 there repeatedly for what are largely incompetently-performed repairs — even I can see this whenI see, following an unsuccessful “repair” episode, that the carburetor float is visibly broken — until the German foreman there refuses me service after hearing I’ve been “bad-mouthing” Armel’s work on this machine) While we are in Onitsha a Pepsi-Cola bottling plant also opens further east off Awka Road, with an American official presiding over the start-up. All of these foreign-owned companies are out of our focus. We here present simple views of some small African businesses, mainly from the two “Market Roads”.

But first, note that along the central portion of Iweka Road Oduah shows a strip of “E” firms. This greatly understates the density of what I see there when I drive between Nnewi Street and Umuoji Street: referring now to the detail map at right,along the right side of the road there I observe a mass of stalls with men selling used-parts (motor car, bicycle, probably lorry) that reminds me of the 1949 Italian film The Bicycle Thief (where the hero searches in vain for his stolen bicycle amongst vast numbers of disassembled pieces in endless arrays of boxes). Unfortunately, I never manage to visit these shops, nor photograph them.

Iweka Road was named after I.E. Iweka-nuno, an Obosi man who served as a houseboy to CMS Archdeacon T.J. Dennis early in the twentieth-century and later wrote one of the first history books in Igbo, about his home town. 26 He competed against an Obosi Warrant Chief who had been imposed by the early colonial administration, in building the road which now bears his name. He bought land from Ndi-Onicha along this road, and thereafter his sons followed him and became very prominent businessmen in this area..

Dr. Jonas Iweka later built Central Hospital, a private institution now (1961) located along Iweka Road near Fegge, intending it to serve the needs of the immigrant Igbo populace of the Waterside. Another of Iweka-nono’s sons, Isaac Iweka, became a a Civil Engineer and Provincial Engineer of the Onitsha Public Works Department (PWD), and in 1962 is a leading businessman in the local motor parts industry. Both men are prominent in Onitsha affairs ( we will encounter them elsewhere in this work).

Note also at right on this closer map, the location of the Ochanja (= “inferior”) Market, with its associated Motor park. I visited this only once and briefly, but it was a substantial and very active complex. My main memory is of a particular product of the numerous tin-workers there: funnels ingeniously fashioned out of recycled beer and soda cans (which in those days were made of much firmer metal than they are in the 21st century), each one displaying a kaleidoscope of colors from the various cans out of which it had been fashioned. (But this was a mere trinket in a very active business place.)

This commercial area was in part associated with the Nnewi transport industry and commerce I have referred to earlier, and was close to the main locus of residence of Nnewi people in Onitsha (at Odo-Akpu). The Street named “Nnewi” in the maps above reflects the importance of residents from that town (and Nnewi people are clustered around St. John’s Cathedral as well). In 1960-62, Nnewi businessmen are seeking to buy more plots of land in this area. This part of Onitsha has become an expanding center for Ndi-Igbo residents who have immigrated here over a considerable number of decades from Nnewi, Obosi, and some other nearby towns.

Some “Engineering”sketches along the “Market Roads”:

Most of the “E”‘s along Old and New Market Road concern bicycles, automobiles, and motorcycles. Printing presses are scattered.

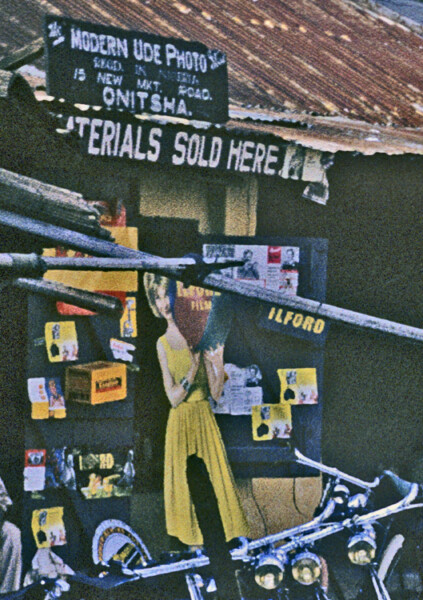

This shop includes bicycle sales and repairs, and also includes a shop selling photographic materials (see below):

At left, at the intersection of New Market and Nottidge road, another very substantial seller of bicycles and bicycle tires.

At left, the only motorcycle sales and workshop I encountered in Onitsha. I almost never saw these vehicles on the road. Since by some calculations they are some twenty times more likely to cause serious injuries to their riders than are ordinary motor vehicles, I regarded this as a blessing for any potential thrill-seekers of this sort.

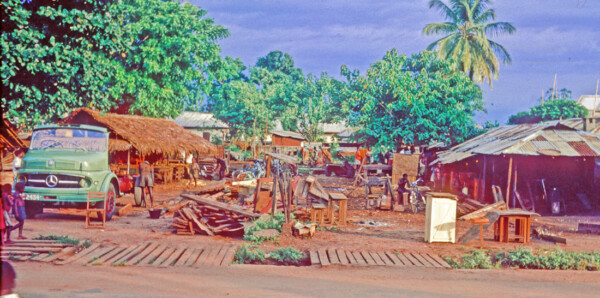

Below, a wood-working site largely devoted to the constructing of lorry bodies. At far left, the imported Mercedes-Benz engine and chassis stand, awaiting the processina number of other purposes.

A number of printing press establishments similar is size to this one were observed, and I visited a few to buy chapbooks. I will say more about this under the heading of “The Arts”.

Varieties of Woodworking (and Shoe-making):

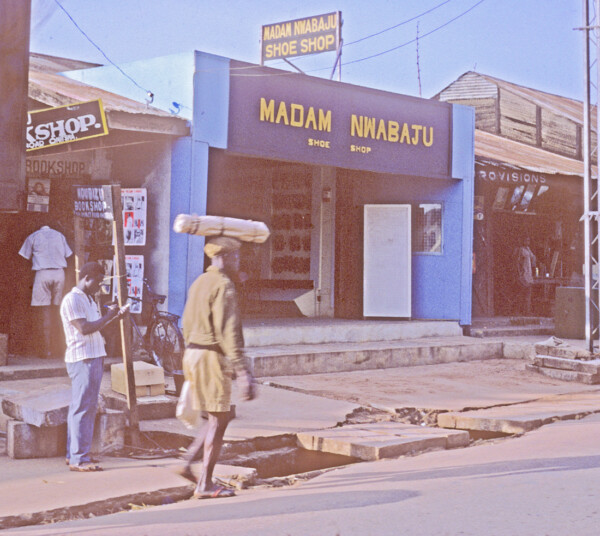

I was struck by the distribution of “shoemaking” in this map provided by Mr. Oduah, since I never saw a single shoemaker workshop in Onitsha. Obviously they were located very inconspicuously, not on public display.. Shoemaking began as repair work only, later expanded to making slippers and sandals using imported leather. Oduah reported one shop on Moore street doing an organized and mechanized business.

The only evidence I saw of this craft was in a small multi-purpose store which had the display for sale you see here at left. This type of sandal apparently had widespread appeal in Onitsha.

This firm at left was not making shoes, but had managed to connect with a Czechoslovakian source of shoes, which she was ow retailing to the public.

In contrast with shoe-making , wood-working shops were very prominent along both New- and Old Market Roads, operating at a variety of scales.

Here the workers of shop stand together. You can see both master an a range of apprentices, some fairly small boys, learning their trade. These apprentice-based shops train their own future competitors.

Below, carpentry devoted to furniture- and coffin-making, at center a “radio and Electric” service, at right a “Technical Institute”.

Note that the building above-center is the former home of the long-departed John Stuart-Young, locally famous (especially among Onitsha people) in the 1920s and 30s, self-labeled as “The Iniquitous Coaster”, and more recently the subject of a thoroughly researched and well-regarded biography of an unusual (more or less openly “gay”) European migrant to Onitsha, treated with respect by Ndi-Onicha ( another example of Achebe’s “occult instabilities”).27

A pair of women coming from the market inadvertently frame the “technical” sign. There indeed is a “technology” worthy of respect.

Here, a woodworker who designs counters but also makes coffins. Several of these are reserved for children.

And, perhaps near the lowest level of “technological” enterprise, these clock-sellers/repairmen display a considerable number of wares.

“Smiths” (Workers in Metals):

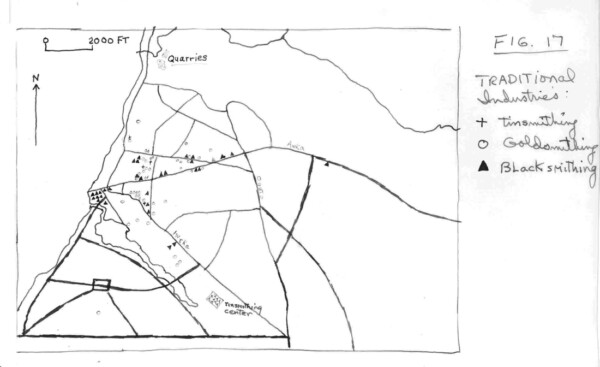

Mr. Oduah compiled the map at left regarding the various types of “smithing” . Note the very large number of blacksmithing establishments, and also the very concentrated “tinsmithing” locations. Goldsmiths were few, working on very small scale, scattered about the Waterside away from the main streets and intersections..

I did not visit the tinsmithing center, the products of which included lamps, cups, pails, trunks, and other objects. I did see during my one (very interesting) visit to the Ochanja market, small funnels obviously made out of scraps from old beer cans (the Budweiser labels obviously visible ). Here, above left, I saw a display of the tin lamps in a shop along Johnson Street.

Awka-derived blacksmithing:

The central — and apparently earliest — of blacksmithing was located in the Hausa Quarter. Then they expanded out along the streets of Onitsha, which was where I encountered them.

Tradition-oriented blacksmiths from Awka maintained a number of shops along New Market Road. At left, iron gongs; at right, the wares of a a seamstress are displayed.

Here you see an array of “traditional” productions:at near left, the large iron cooking stoves; near right, a variety of ritually significant objects: iron gongs for rituals, staffs for various ritual offices, chains.

In this small stall, displaying similar traditional materials, the seller decorates his with some striking artworlks on a pillar.

Sometimes, the presence of a smithing operation was indicated externally solely by massive displays of raw product at the entrance.

Cloth, Clothing, Textiles, Tailoring

A very large component of this field of materials and products is located in the Main Market — the entire Southern “E” of the roofed building is devoted to them. Mr. Oduah reported a substantial, mechanized textile-producing shop in Fegge but I did not see it. Shops devoted to clothing and tailoring along the streets were rare and mainly small. Oduah wrote dismissingly of their quality, detecting serious lack of training in the necessary arts.

There definitely were some good tailors in the Waterside, since I managed to be fitted for and buy an Agbada suit that was quite fine, and Helen also bought and wore a number of really fine locally-made dresses. Unfortunately my memory fails to record where we got these things and I neglected to photograph the locations.

Personal Services; “The Arts”:

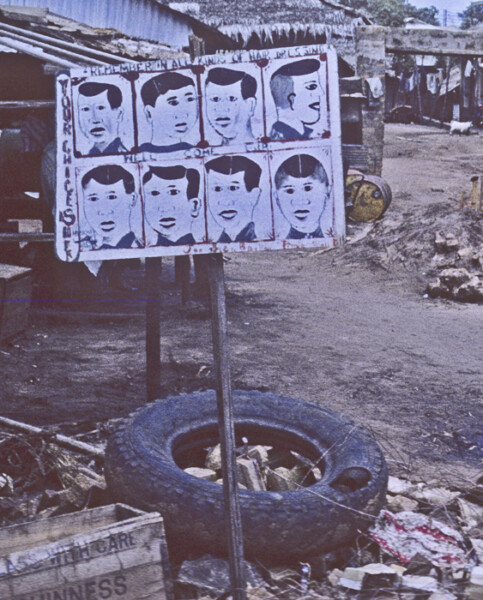

I frequently saw signs promoting barbershops along the streets of Onitsha, sometimes in unlikely places.

When we first arrived in Onitsha, I hired a roving barber to cut my hair, but when he couldn’t resist impressing upon me the wonders of Jehovah’s Witnesses, I sacked him and Helen cut my hair thereafter.

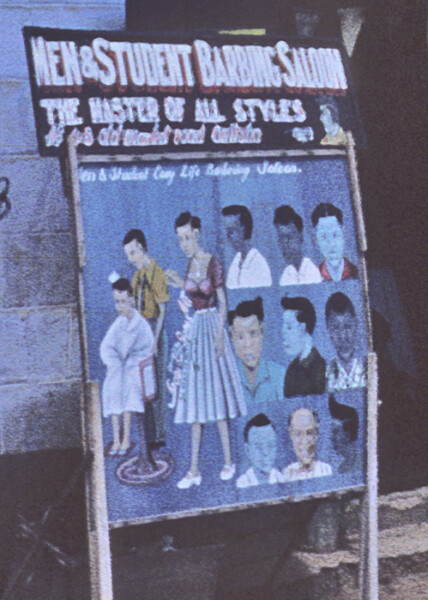

At left, beside a batteries shop, was the most substantial one I encountered. Defining themselves as a “New and Student Barbing Salon”, they boast that they are “The Master of All Styles”.

Works of art serve to convey a wide variety of messages:

Signs like this one — advertising the “Men & Student Barbing Salon”, “The master of All Styles” — are scattered widely along the streets of Onitsha, and were produced in local artists’ Studios.

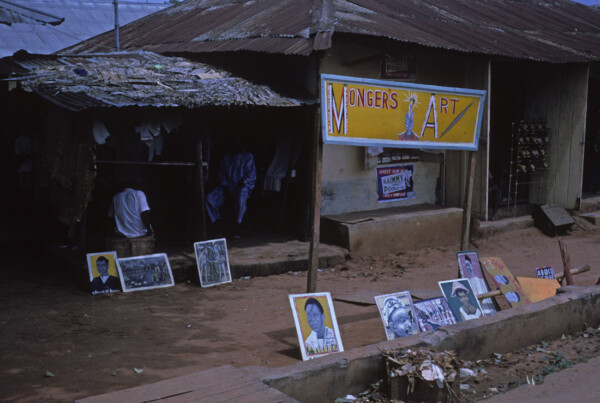

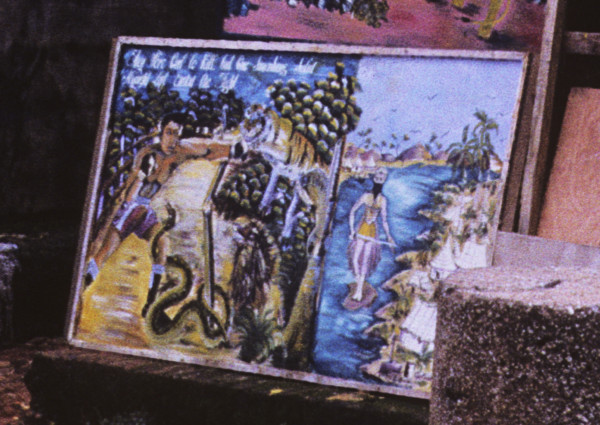

One of these was “Monger’s Art”, at left, emphasizing portraits of currently-admired political figures as well as portraits of scenes.

One of these is a very literalist icon of Christian imagery. This might seem an unlikely image to put on a wall of one’s house, but the missionary emphasis at this time (especially on the Roman Catholic side) is very strongly good-vs-evil in an ab;solute sense. Interestingly, I saw its categorical opposite in a sense in some men’s rented rooms along the market roads: framed photographs of Adolph Hitler. When I asked why, the response was,”He strongly fought the British Colonialists;!”, another very vivid view of “good vs. evil”.

For example, the one at far left depicts what appears to be a fantasy scene of plentiful delight (with a large threatening snake complicatng matters). This looks like another tale of “forbidden fruit”. (Startling imagery, it seems to me.)

This shop sold medallions of various kinds. These presumably propose many subtle distinctions of identity.

Book-Writing as an art form:

The numerous bookstores scattered along the main streets of Otu provided another important source of local artistic production: the Onitsha “Chapbooks”, locally printed and stories and guidebooks written mainly by local Ndi-Igbo immigrants during their spare time.

These books became prominent in literary and social-scientific circles in the 1960s when prominent writers like Chinua Achebe called attention to them as interesting works of artistic creativity

I collected a substantial number of them during my fieldwork at that time, and brought them to Tucson when I moved to the University of Arizona Department of Anthropology. Since my office space was limited, I kept some of them on shelves in an office nearby occupied by persons in the Bureau of Applied Research in Anthropology, where however they were accidentally included in an act of disposal of another colleague’s research materials when he was expelled from that department. Consequently — to my endless chagrin — these research materials were permanently lost to me.

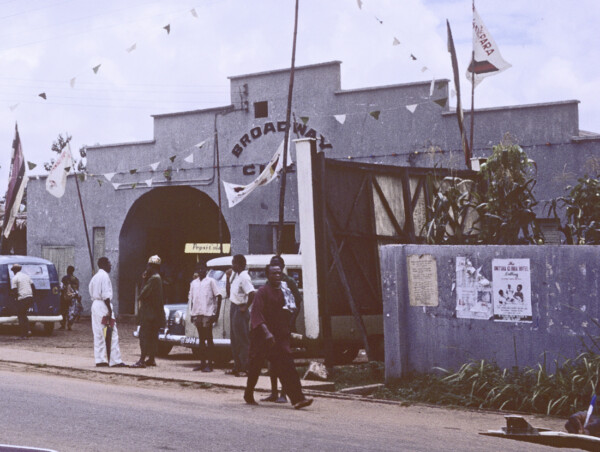

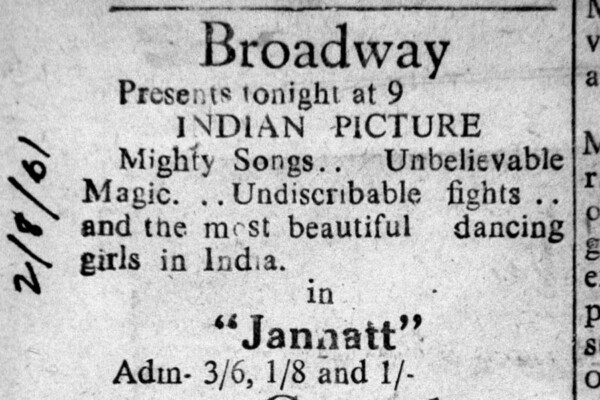

Interested readers will find the book on this subject written by Emmanuel Obiechina (1972) informative. He points out that the readers of these works are “grammar and elementary school boys and girls, lower-level office workers and journalists, primary school teachers, traders, mechanics, taxi drivers, farmers and the new literates who attend adult education classes and evening school”. The focus of the writings is on helping their readers to cope with the complications and dangers of living in a large city. Much imagery from these books is drawn from the current cinema, and Onitsha had two, which drew large, enthusiastic crowds:

We attended one film here, a black/white pre-war English thriller with sharp physical actions, which drew loud, in-unison responses from many of the seated crowd. It was a much mroe intense experience than we had encountered before, “back in the U.S.A.” Enjoyable, for sure.

That the influence of cinema on the consciousness of Onitsha’s occupants was both wide and deep was reflected in the presence of a local “Cowboys’ Association”, an entity apparently present in a number of Nigerian cities during the early 1960s. I only encountered the group once, in a parade conducted by them along a Market Road, and was without my camera, so I failed to record their presence. However, cowboy chaps, boots, and vests, pistols, holsters and hats were numerous, and the spirit of the participants highly assertive.

Some Onitsha establishments designed for pleasure:

The “Palmwine Bars”:

I typically did not photograph the Palmwine Bars I saw in Onitsha, but I was visiting Ogbe-Umu-Onicha one Sunday and encountered this very active one, right near Ononenyi Emejulu’s house, where we were visiting at the time. You can see it’s a successful one from the many empty palmwine pots strewn about the entryway (and also from the evidence of people present).

Palmwine Bars were in fact widely distributed around Onitsha, with some located in the Inland Town as well. Ikena Ikemefuna occasionally invited me to share someof the palm wine he had just obtained, and it was phenomenally delicious since he always offered it “straight from the tree” . However, it also very quickly soured, and no technology existed to “bottle” it in pure form.

Once Helen and I invited two new Peace Corps workers to share some fresh, but they found it somehow not to their taste and so we found it necessary to drink up the remainder after they left — there was no alternative. It was sufficiently alcoholic that we went to bed and slept for a while afterwards.

Palmwine sellers were definitely active all over town. Here at left you see one of the way-stations at a corner of New Market Road where men charged with delivering it met to consult regarding distribution matters.

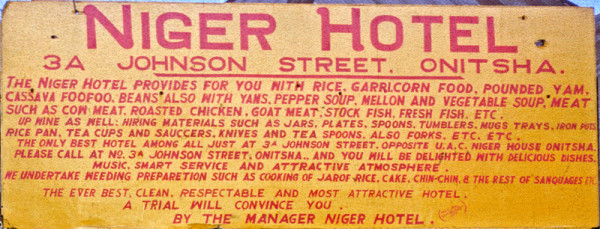

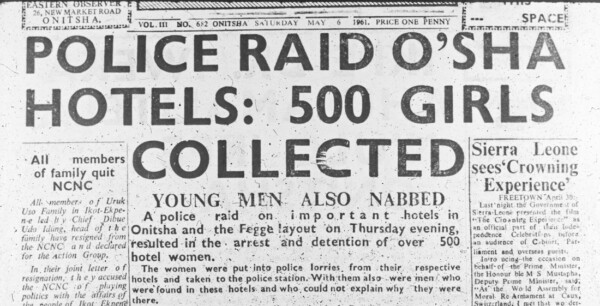

The “Hotels”:

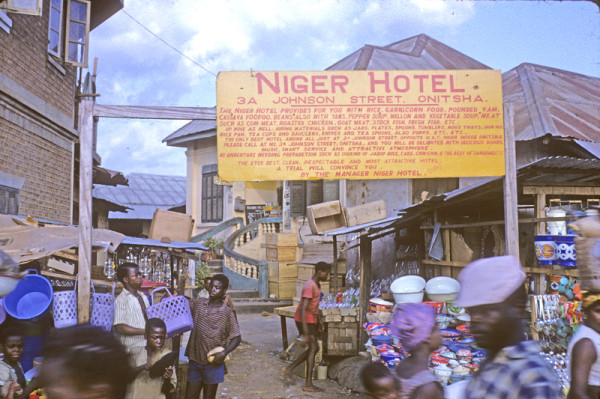

The presence of thousands of traders (both inside and outside of the Main Market area in Onitsha) has stimulated much private enterprise in the form of what local people call “Hotels”, like this one, the Niger Hotel. In front of the moderate-sized building that houses it, this one proclaims in detail the foodstuffs it is ready to serve (and to cater):

These “Hotels” range in size and services from tiny stalls in the Main Market serving food and drink there, to one-room buildings scattered around town that provide both food and overnight housing for travelers, to much larger and more multipurpose serving establishments that offer food, drink, dancing and other programmed entertainment, and/or prostitution services. A sign for the “Gay Palace Hotel”, for example, promises “Gaiety Galore”.

The one advertising above above emphasizes its food-service. Further north, at the intersection of Johnson Street and Old Market Road, one encounters below the River Side Hotel, a much more substantial (and complex) establishment:

On the right-hand side of this image, note a sign giving the logo of the owner and operator of this large Hotel, one J.J. Enwezor. Then-Nnanyelugo (his Ozo-title name) Enwezor is one of a very few indigenous, Ndi-Onicha men living in Onitsha who own a substantial profitable business here. And he owns not only one but many, some of them much larger operations than the one whose building you see here. Nnanyelugo (later, Igwe) Enwezor will figure as one of the most prominent figures in this entire book, so I don’t want to ignore him here (and some of his agents will reappear in another context not far from this very spot in our story, in fact right across the street, on the side-walk spaces of Old Market Road alongside Ani-Onicha (See Chapter 6, “Igwe Enwezor Petitions Ani-Onicha”.).

Helen and I scarcely ever visited an Onitsha Hotel, but we went to a celebration once at a very large one in Fegge, the Central Hotel, where large numbers of local people danced and partied to an Orchestra performing on the upstairs floor of the building. Later, we arranged for Helen to interview some of the prostitutes who worked and resided there, in their small crib-stalls downstairs. Since Helen then could not drive, I escorted her to the hotel one Friday noon in our Motor-Machis and then returned to retrieve her in the late afternoon.

I had forgotten it was a weekend day, (Friday) and when I arrived the lower-level part of the building (a cavernous, somewhat labyrinthine place it seemed to me), and crowded full of young men milling about with nervous intensity. I became anxious, not having any idea where I might find her and feeling very uncomfortable, so when I saw a man there I recognized, I blurted out to him in the midst of the crowd, “Have you seen my wife?” I will never forget the complex flow of movements than played across his face as he tried to control his response.

(Helen made some interesting findings about the women All were non-Igbo-speaking in origin, mostly from the Northern Region, and were carefully saving their earnings to support education of their family members at home. They were also well-organized as an interest group within the Central Hotel, and could proudly tell of cases where members joined to beat up and throw out men who mistreated any one of them. Helen used the research in her later work, but the material as a corpus was never published.)

Below, the “Easy Life Hotel and Bar on Old Market Road, where women may also be seen pensively gazing out the upper-floor windows.

One afternoon, Obiekwe Aniweta (always an active admirer of female social forms), invited me to take a beer in this place. We went in, and sat near a number of women there, all of them quite corpulent to my eyes.. (This was definitely the preferred female form for women from the perspective of most local men in the early 1960s.) I displayed no interest — and indeed had I felt any would have had to decline any active attention, since such an action would have spread my reputation quickly everywhere in the Inland Town – as Aniweta Observed to nobody in particular,, “Mr. Henderson is not Serious!” So we left very soon thereafter, and nobody raised the issue to me again.

At left, the Bolingo Hotel, a large pink-colored building on New Market Road, located three substantial houses up-hill from the UAC Headquarters building.

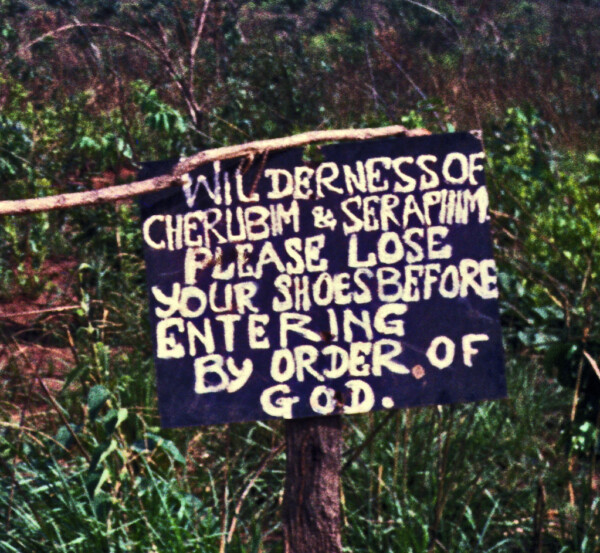

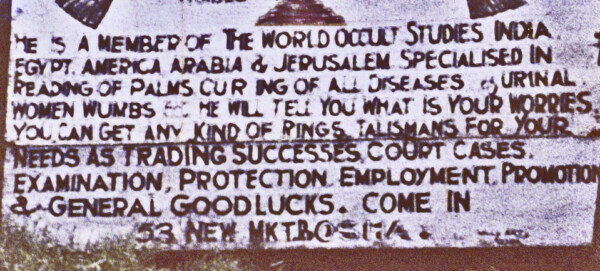

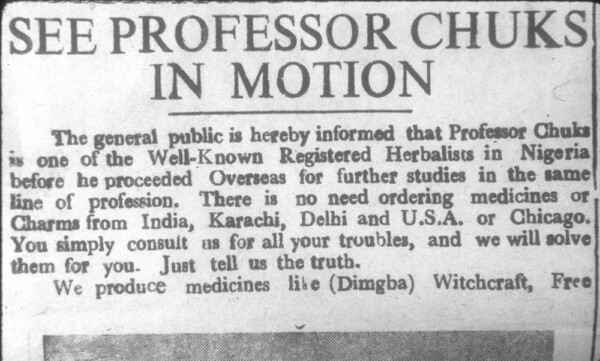

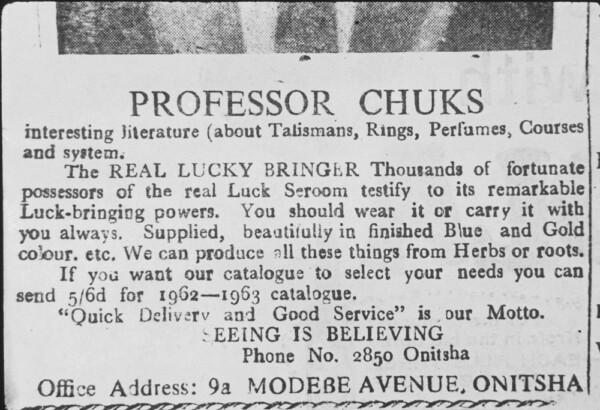

This “Eastern Nigeria Hotel”, located further up New Market Road near its apex meeting with Old Market Road, is a much smaller operation than the others shown here, but it displays an appealing boldness. Under the name logo are the Igbo words “Anyi Nwe” (“We have”), below that, “Motto Quality First”, and below that, “We Maintain Classical Restaurant”. The two beautiful women/hostesses are obviously very stylishly dressed.